The Del Monte deaths: one year on, what’s changed?

There have been no killings at the brand’s massive pineapple farm in six months, but violence continues to plague the local community

Felister Wairimu had endured a restless night with her newborn baby, the youngest of her five children, when she heard a commotion outside. She stepped out onto her balcony, holding the hand of her toddler. All of a sudden she felt something sharp slice through the back of her neck. Reaching back, she saw blood.

She’d been shot.

Out on the street, police were clashing with local pineapple thieves after an attempt to raid fruit from the huge Del Monte plantation in nearby Thika, central Kenya. Felister was struck by a stray bullet, as was her neighbour.

“This violence is now spreading to our homes, even when we have nothing to do with pineapple stealing,” Felister’s husband Henry Ng’ang’a told the Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ).

The incident, in the village of Makenji on 23 May, was one of a series of violent outbreaks to have occurred since Del Monte announced an overhaul of the farm’s security in March, sacking more than 200 guards and bringing in the global contractor G4S. At least four others suffered injuries from gunshots and rubber bullets fired during confrontations that week.

G4S told TBIJ that none of its guards are armed with weapons of any kind, nor do they operate outside the boundaries of the Del Monte farm.

One year ago this week, TBIJ and the Guardian revealed a decade-long series of allegations against Del Monte security guards, including beatings, rape and murders. In response to those revelations, Del Monte commissioned a human rights assessment and then, in line with the recommendations, replaced the farm’s security operation.

Three British supermarkets – Tesco, Waitrose and Asda – stopped stocking pineapples from the farm in the wake of the reporting. Sainsbury’s has also stopped taking orders from the plantation.

However, both Morrisons and Iceland continue to sell pineapples grown by Del Monte in Thika.

A spokesperson for Morrisons told TBIJ it was urgently investigating recent allegations of violence, adding: “We have been regularly monitoring the implementation of the human rights impact assessment action plan and the comprehensive remediation plan with Del Monte.”

Iceland did not respond to requests for comment.

Historical claims

The scale of the violence and its impact on the local community was captured by the UK law firm Leigh Day last year. In a letter to Del Monte, the firm detailed 146 alleged incidents involving 134 people. In response, Del Monte said it took the claims “extremely seriously” and had “instituted a full and urgent investigation into them”.

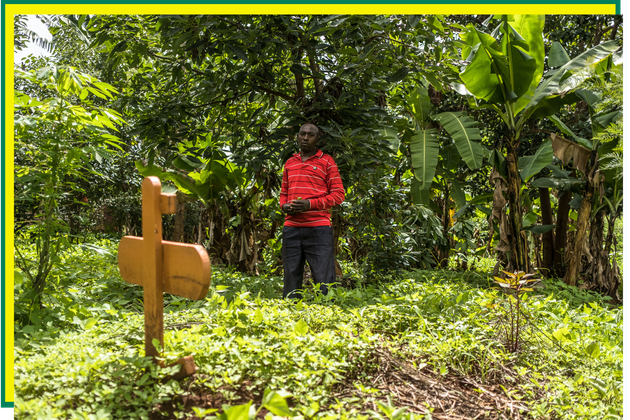

One of the most shocking cases was that of Stephen Thuo Nyoike, who was found strangled with a wire by the side of a road in 2022. According to witnesses, he was last seen alive being beaten with wooden clubs by Del Monte security guards. He was 22.

Joel stands over the grave of his son, Stephen

Brian Otieno for the Guardian/TBIJ

Joel stands over the grave of his son, Stephen

Brian Otieno for the Guardian/TBIJ

His father Joel described him as “a good kid” who was planning to set up his own welding workshop. He told TBIJ that the pineapple thefts are mostly “driven by peer pressure and poverty”.

For many years, tensions have been running high between the farm and a local community blighted by deprivation, unemployment and drug use.

In June 2023, the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights, the national human rights watchdog, launched an investigation into the farm. It called on Del Monte to “take immediate actions to ensure effective remedy” for those who have alleged violence.

But the brutality continued. In November, Peter Mutuku Mutisya, 25, was found dead in a dam on the farm after embarking on a botched pineapple raid with two other young men. Over Christmas the bodies of a further four men were dragged from a river by the farm, after a confrontation between guards and pineapple thieves. Witnesses said they saw guards beating the victims.

George Kinyanjui was hit by a stray bullet when coming home from a night shift in May

Edwin Okoth

George Kinyanjui was hit by a stray bullet when coming home from a night shift in May

Edwin Okoth

Concerns were raised in both cases over Del Monte’s involvement in the post-mortem process, with the company sending its own pathologist to examine and report on the bodies. In response, Del Monte said there were “no indications of foul play” in the post mortem process for Mutisya, nor the deaths over Christmas.

Witnesses to the four deaths at Christmas accused Del Monte representatives of offering bribes to young men who would support the company’s version of events. In a statement at the time, Del Monte said: “We have submitted our evidence, which contradicts the information you have presented, to the appropriate legal authorities.”

The Kenya National Commission on Human Rights investigated these five further deaths, which are now part of a civil court case brought at the end of last year. The case, which calls for access to information and damages for victims, includes more than 2,000 petitioners.

In November, social audit consultancy Partner Africa also delivered the human rights impact assessment commissioned by Del Monte to the fruit giant, and sent a summary and its recommendations to UK supermarkets.

Several NGOs raised concerns that Partner Africa was not asked to investigate the specific allegations of violence and deaths. Nevertheless, the findings, seen by TBIJ and the Guardian, were highly critical and concluded that the farm was causing numerous major human rights harms to local communities.

“It is crucial for companies to demonstrate that they have engaged in a dialogue with any stakeholders reportedly affected by allegations of abuse,” said Áine Clarke at the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (BHRRC), a non-profit working to advance human rights in business. (BHRRC was not among those that criticised the scope of the Partner Africa investigation.)

Clarke said that companies must tell victims about the outcomes of any remedy process, as well as include corrective measures to prevent human rights abuses happening again.

Del Monte pineapples on sale in Morrisons in June 2024

Emily Goddard

Del Monte pineapples on sale in Morrisons in June 2024

Emily Goddard

March 2024, when Del Monte fired more than 200 of its guards and brought in G4S, looked like a turning point. The company also advertised for a human rights manager and welfare and diversity manager.

What followed was a period of calm. According to one young man who says he has been to the farm several times to steal pineapples to make a living, “when the G4S guards first came they never used to beat us up. They would only tell us to leave the farm or chase us away and cut the pineapples”.

George Kinyanjui, a quarry worker, also said the overhaul prompted a spell of peace. “[I] could see the youth just stealing pineapples and no one seemed to be doing anything about it,” he told TBIJ. But then, coming home from a night shift one morning in late May, he was hit by a stray bullet. He was treated in a nearby hospital and released that same day.

Felister was treated at a local hospital after being shot on her balcony

Edwin Okoth

Felister was treated at a local hospital after being shot on her balcony

Edwin Okoth

Later that week, Felister was shot on her balcony. She too was treated in a local hospital and discharged later that day. She feels lucky to have “escaped death narrowly”, but her husband Henry is angry: “What value do pineapples have over our lives and businesses?”

G4S Kenya said its guards had been “expertly trained in de-escalation techniques, human rights considerations and in the minimum use of force”. A spokesperson added: “Our security officers are stationed at the farm only and have no involvement in activity that may occur outside its boundaries.”

Neither Del Monte nor Murang’a county police responded to requests for comment.

The relative calm appears now to be over. For those already grieving, the brief pause in violence offered little respite.

Joel, the father of the strangled man Stephen, travels through the farm every day for work. The Del Monte vehicles he sees are a daily painful reminder of his son’s death, and the wait for justice. A year on from the first public report of his son’s death, he says, “things are just as they have been”.

Header image: Felister Wairimu on her balcony, where she was shot. Credit: Edwin Okoth

Reporters: Edwin Okoth and Grace Murray

Environment editor: Robert Soutar

Deputy editors: Katie Mark and Chrissie Giles

Editor: Franz Wild

Production editor: Frankie Goodway

Fact checker: Somesh Jha

Our Environment project is funded partly by Quadrature Climate Foundation, partly by Hampshire Foundation and partly by the Hollick Family Foundation. None of our funders have any influence over our editorial decisions or output.

-

Area:

-

Subject: