Online gig work is feeding Russia’s surveillance machine

TBIJ can reveal that the technology used to repress dissent against Putin’s authoritarian regime is powered by unwitting gig workers in the global south

The world was watching as people gathered in Moscow to pay their respects to Alexei Navalny, the opposition leader who died in a Russian prison last month. So too were about 200,000 cameras that make up the city's vast surveillance system, one of the most extensive in the world.

They captured images of a woman laying flowers on the day of Navalny’s death and another in the throng of people at his funeral. Some were identified by the sophisticated facial recognition technology that is integrated into Moscow’s street cameras. And at least 19 of those picked out by the cameras or in images posted to social media were detained by the authorities, according to the Russian human rights group OVD-Info.

Alexey Gusev, watching from afar, was dismayed by what he saw unfolding. The former Moscow politician had attended a protest in support of Navalny in January 2021, and two months later received a phone call from the police. They informed him that he had been caught on camera at the rally and asked him to report to a local station, according to Gusev.

“You can be in any place in Moscow, you can be recognised immediately and this can be used against you,” Gusev said.

Within two weeks, Gusev had fled Moscow to escape charges that he had organised and attended the protest, although he received a fine for “taking part in an uncoordinated mass action”.

“I had to leave Russia because I realised that this case was becoming serious and the criminal conviction was highly likely to happen,” he said. Gusev does not deny attending the protest but says he was not an organiser.

“There is no question: the current situation is deeply discouraging for all of us,” Gusev wrote in a blog for the University of Münster, Germany, where he is a doctoral candidate. “The knowledge that meaningful protest is virtually impossible increases the sense of isolation among opposition figures – especially those in prison.”

Facial recognition technology is deployed in the public surveillance systems of a number of Russian cities and is a key weapon in the arsenal used to contain dissent against president Vladimir Putin.

Its usage is most extensive in Moscow, where it has been integrated into CCTV cameras since at least 2017. In 2020, when Covid-19 restrictions were in place, Moscow's Ministry of Internal Affairs announced that its network of 178,000 cameras had caught about 200 “quarantine violators”.

In 2021, when Navalny, then the biggest thorn in Putin’s side, was jailed, the facial recognition system was soon deployed against those who took to the streets in protest – scanning faces across the city and seeking matches with official watchlists. OVD-Info data shows that 454 protesters were detained in the ensuing crackdown after their images were captured on facial recognition.

The following year, the cameras were used to target those who opposed Putin’s war in Ukraine. “After the full-scale invasion… facial recognition technology began to be used for preventive detentions,” said Maria Nemova, a strategic litigation lawyer at OVD-Info.

“People who had previously participated in protests or expressed dissent in another way were detained in the metro on national holidays or important events such as mobilisation announcements,” Nemova said. “In most cases, these detentions aimed not at legal consequences but at intimidation to discourage future protest participation.”

A spontaneous memorial to Alexei Navalny in St Petersberg after his death at a Siberian prison earlier this year

Artem Priakhin/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

A spontaneous memorial to Alexei Navalny in St Petersberg after his death at a Siberian prison earlier this year

Artem Priakhin/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Now TBIJ, in partnership with Follow The Money and Paper Trail Media, can reveal that the technology used to repress dissent against Putin’s authoritarian regime is powered by unwitting gig workers in the global south. A sprawling global network supporting Russia’s surveillance regime draws in US investment firms, one of Russia’s biggest tech companies and two companies sanctioned for their alleged role in Putin’s oppression.

At the heart of it all is Toloka, a little-known tech platform that recruits the gig workers and raises questions about the effectiveness of EU sanctions. Before a recent restructure, all of Toloka was ultimately owned by Yandex, a Russian tech giant with major shareholders in the west.

Toloka told TBIJ that none of its EU, Swiss or US “entities have ever provided services or received any payments” from the surveillance companies in question. Instead, it said, a Russian subsidiary of Yandex had handled them.

Moscow’s surveillance programme buys facial recognition tech from one Belarusian and three Russian companies, among them Tevian and NTechLab.

NTechLab was founded in 2015 and swiftly proved one of the most effective facial recognition businesses, topping a ranking run by the US’s Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology.

In 2016 it caused controversy with the release of its FindFace app, which could identify people using data from the Russian social network Vkontakte, prompting warnings of an “end to public anonymity”. Since 2018 it has been part owned by the Russian defence company Rostec State Corp.

And during the 2018 World Cup NTechLab said its software was used to round up about 100 wanted criminals and its technology was subsequently installed on the Moscow metro network.

Putin’s presidential office plans to use NTechLab software in a secret project for a “Video Stream Processing Centre”, which will sync up existing regional cameras and effectively roll out Moscow’s surveillance system nationwide, according to documents revealed as part of the Kremlin Leaks project.

The 3-year budget for the project is around 11bn rubles (£93m), with 83m rubles (£700,000) a year set aside for NTechLab software licences. The project’s aim is to “ensure the timely identification of threats” and check “individuals for destructive and/or disloyal behaviour,” the documents show.

Tevian meanwhile has kept a lower public profile, but appears to have been founded by Moscow State University staff in 2010.

Contracts published by Russian authorities in 2022 revealed that both companies were contracted to surveil Moscow’s streets. Last year, NTechLab told Reuters its software was no longer used by the Moscow metro, but would not comment on whether the rest of the city's surveillance apparatus was using its tech. It added that its software “is independently managed by the customer”.

In July 2023, the EU placed Tevian and NTechLab under sanctions because their facial recognition technology was used for “serious human rights violations in Russia, including arbitrary arrests and detentions”, although neither has been sanctioned in Switzerland.

EU law forbids individuals and companies from receiving payments from or providing services to sanctioned entities.

This, however, has not stopped Tevian and NTechLab receiving the data they need to feed their surveillance software.

Both companies obtain vast amounts of data to bolster their image libraries and use outsourced workers to identify and label images and videos from surveillance cameras. This helps the machines learn and become more effective.

Between 2019 and 2023, the two companies obtained these services from Toloka, which is registered as three separate companies in the Netherlands, Switzerland and Russia. All are subsidiaries of the Russian tech giant Yandex NV, also based in the Netherlands. Since the West sanctioned thousands of Russian individuals and companies in response to the invasion of Ukraine, Yandex has been attempting to reorganise its global operations, splitting its Russian and international businesses.

Yandex’s Russian arm told TBIJ that it had recently created a separate crowdsourcing platform called Yandex Tasks for Russian users and clients. It began migrating Russian clients from Toloka to Yandex Tasks in December 2023, it said. The company confirmed it was still working with NTechLab as of this month.

Toloka told TBIJ that the Russian Toloka subsidiary had a contract with Tevian and NTechLab, but that “volume of work offered through the platform during the transition period by the two companies was immaterial, both financially and in terms of the number of tasks.” Toloka said Yandex NV has never “received any payments from NTechLab or Tevian”. Toloka added that it does not cooperate with companies that violate terms of service rules or are using them for unethical purposes.

While Yandex itself is not subject to EU or US sanctions, three of its former directors have been sanctioned by the EU. Yandex’s co-founder Arkady Volozh, has recently had his sanctions lifted.

Arkady Volozh with Vladimir Putin at Yandex's HQ in Moscow in 2017

Mikhail Svetlov/Getty Images

Arkady Volozh with Vladimir Putin at Yandex's HQ in Moscow in 2017

Mikhail Svetlov/Getty Images

Volozh resigned as CEO in June 2022, the same day sanctions were imposed, but he still owns 8.5% of Yandex via a family trust that retains 45% of the voting rights. Yandex says he has promised not to give the trustee voting instructions and that these votes will follow recommendations from the board’s independent members.

Yandex NV is listed on both New York’s Nasdaq exchange and the Moscow Stock Exchange. Nasdaq suspended trading in Yandex shares shortly after the invasion, a restriction that has remained in place since.

In February, Yandex announced that a consortium of investors, including parts of Russia’s energy industry, had agreed to pay $5bn for its Russian assets, potentially allowing trading to resume on the Nasdaq.

About a quarter of Yandex NV is still owned by institutional investors, including the asset management giant Fidelity, the asset management arm of UBS and Norges Bank, Norway’s sovereign wealth fund.

Other Western investors such as Invesco and Capital Group appear to have offloaded all or most of their holdings over the past year. While Yandex shares cannot be traded on Nasdaq, they can be sold on “over the counter” markets where stocks are traded directly between two parties.

While Yandex immediately started responding to sanctions, the relationship between the Toloka platform and Tevian and NTechLab remains an open question.

TBIJ reporting suggests Toloka has continued to work with NTechLab, and potentially Tevian, after they were sanctioned by the EU in July 2023. Screen recordings of gig workers performing the same NTechLab task were posted to YouTube within a day of each other in September 2023, and in one the phone used to complete the task briefly shows news headlines from September 4.

A screenshot of a single Tevian task was also posted anonymously to a Facebook group for Toloka workers in December 2023, although it is unclear when this was posted to the platform.

The EU has sanctioned more than 2,000 individuals and companies since the invasion of Ukraine, but enforcement remains patchy, according to research by the defence think tank RUSI.

Toloka says that the engagement with the sanctioned entities was all done via a Russian subsidiary company. “If those companies are sanctioned, then making resources available to them is prohibited,” said one EU diplomat.

“The moment they receive payments from a sanctioned company, so the moment this transfer enters an EU banking system, it should be frozen.”

“The question is… are they doing trade with those sanctioned entities directly? Then it would be a direct violation of sanctions.”

A Brussels-based EU sanctions lawyer said: “I cannot say with absolute certainty that EU law would apply, but what I can tell is that the EU company would likely be at risk of being viewed as engaging in a business that may contravene sanctions.”

Tevian and NTechLab’s contribution to Moscow’s surveillance system only sharpens the issue for Toloka. The relationship represents a sliver of the global gig economy in which workers from lower and middle income countries accept low-paid work to support the world’s biggest tech companies.

Toloka has sourced workers for Tevian and NTechLab to improve the software that identifies individuals. TBIJ reporting found workers in India, Turkey, Pakistan and Bangladesh had done tasks for the two companies, either providing photos to build their image libraries or labelling footage to improve automatic recognition of people and actions, since 2019.

Santosh*, a Toloka worker based in India, was concerned to learn that the tasks he had done for NTechLab might have contributed to politically-motivated surveillance. “If it is to help the government then this is good, but if they are using this for a bad purpose then this is definitely harmful for the entire society,” he said.

“Nobody knows how they are training the data and what they will do in future. So it's a great risk for the entire world I think.”

Facial recognition software, like that produced by Tevian and NTechLab, uses a branch of machine learning in which models are trained on vast libraries of images and eventually learn to recognise patterns in the geometry of faces.

In a typical data collection task, NTechLab requested photos from people of “Afro, Latino, Asian” ethnicity, offering $0.50 for 5 photos. Facial recognition software generally underperforms on non-white faces, in part because existing data sets skew white, and this task appears to be designed to improve performance on specific ethnic groups.

Tasks posted by Tevian were related to “facial liveness”, a feature which both Tevian and NTechLab sell as a core part of their facial recognition product and is used to distinguish a real person from an image or video.

Toloka workers are told little about the ultimate purpose of their tasks, although the names of the companies who requested the work are listed. As well as facial recognition companies, Toloka also contracts workers for self-driving car companies, search engines and online shopping sites.

Khalil*, a former Toloka worker based in Kenya, said he felt uncomfortable after sending in photos of his face, and tried to find out more about how they would be used by posting on an online forum for Toloka workers.

“I was sharing my face, and I couldn’t find out,” he said. “I tried … to see who I was sending them to and I was not satisfied with what I got.”

The investigation also raises questions about the privacy of people whose images end up in Toloka datasets.

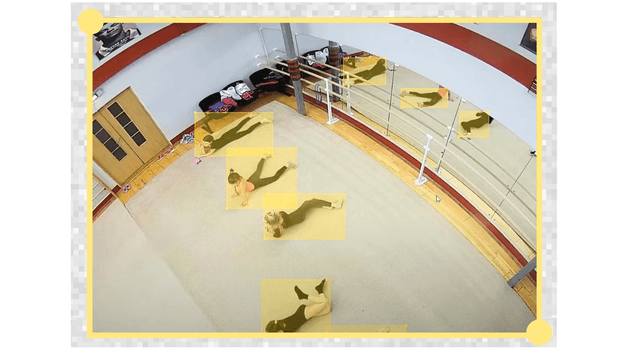

In one annotation task, NTechLab asked Toloka workers to “draw rectangles on human bodies” on photos taken from a CCTV camera located in a gym. The images were taken during what appears to be a dance class for young girls, some shown lying on the floor in leotards.

A screenshot from a task on Toloka for NTechLab that asked users to draw boxes around human bodies

A screenshot from a task on Toloka for NTechLab that asked users to draw boxes around human bodies

In May 2021, Julia Scherbakova, a local politician representing the same Moscow district as Gusev, was getting ready to drop her daughter off at nursery before work. But, she said, when she opened her front door, two policemen were waiting.

They said they had an image of her attending a pro-Navalny protest and asked her to come to the station. With no child care on hand, the policemen escorted her and her daughter to nursery and then, having dropped the child off, took Scherbakova to the station.

She was detained for a few hours but released without charge – Scherbakova says it was a case of mistaken identity. She had already been thinking of leaving Russia, but said her detention helped her make up her mind.

“When people are doing such things, it’s not normal. And I don’t want my kids to live in such an environment,” she said.

OVD-Info data shows 141 people were detained preventively via facial recognition cameras in 2022. The technology did not lead to a significant number of detentions in 2023, Nemova said, though its usage has increased again following the death of Navalny.

Many Russian opposition figures and anti-war activists remain in exile. Scherbakova now lives in Spain, while Gusev took a circuitous route to Germany by way of Moldova, Georgia and the UK.

“What is happening now in Russia, it’s actually a dictatorship,” Gusev said. “This is not power that can be changed in a democratic way, because there is no room for legal struggle against this government.”

He hopes to return to Russian politics one day, but does not expect it will happen any time soon. “I believe in the Russian people. And I’m sure that in the future, things will change.”

*Names have been changed to protect sources.

Reporters: Niamh McIntyre, Leonie Kijewski, Hannes Munzinger, Carina Huppertz and Lukas Kotkamp

Tech editor: Jasper Jackson

Deputy editor: Katie Mark

Editor: Franz Wild

Production editor: Frankie Goodway

Fact checker: Josephine Moulds

A version of this story was also published with ZDF and Der Spiegel in Germany and Der Standard in Austria.

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s AI Accountability Network. Our reporting on Big Tech is funded by Open Society Foundations. None of our funders have any influence over our editorial decisions or output.

-

Area:

-

Subject: