Visa system forces care workers to stay silent on rape and abuse

Content warning: This story contains references to rape and sexual harassment

Abena*, a migrant worker from southern Africa, was repeatedly raped by her manager at a UK care home but felt unable to report him to the police for fear of losing her job and her visa.

Bernice*, from the Caribbean, was sexually harassed by her landlord in the accommodation arranged by her employer, which sponsored her work in the UK.

Then there’s Chidera*, a live-in carer from Ghana who once went nearly four months without a day off. After complaining to a manager, she was threatened with being dismissed and having her visa revoked.

They are among dozens of migrant care workers who have travelled to the UK to fill vacancies only to find themselves exploited and silenced. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ), working with Citizens Advice, has gathered the testimonies of almost 175 people working for approximately 80 care providers via the health and care worker visa.

Their stories reveal that the people who make up a vital section of our social care workforce fear raising concerns about labour abuses – in large part because the existing visa system makes them dependent on their employer for their right to stay and work in the UK. And any complaint, even if upheld, can start a ticking clock leaving them with barely two months to avoid the risk of deportation.

“We work on a lot of difficult issues at Citizens Advice, but this is one of the most heartbreaking because of our limited ability to help people find a way forward,” Kayley Hignell, its interim director of policy, said.

“Our investigation shows that there are potentially thousands of people trapped in a system which leaves them vulnerable to abuse and threats, powerless to complain, and often losing thousands of pounds. These people are skilled professionals who keep our healthcare services running yet … the best we can sometimes do is help them access a food bank.”

Andrew Gwynne MP, the shadow minister for social care, said the shocking findings highlighted how the government had failed in its promise to fix the crisis in social care. “It is vital that we ensure we have a system where exploitation of overseas workers is not tolerated, and steps must be put in place to stop those who perpetrate abuse,” he said.

‘If she is dismissed, she will have nothing’

Early last year, staff at Citizens Advice, a charity that provides confidential support on issues including debt and housing, noticed an increase in calls from people in the UK who were on the health and care worker visa.

Concerned by the trend, Citizens Advice collected information recorded by its advisors to assess the scale of the problem. In total, the charity gathered evidence from 150 workers, although the true number of people affected is likely to be far higher.

The charity then shared anonymised information about the callers with TBIJ as part of our investigation into exploitative and precarious working conditions faced by migrants in the UK.

In those calls and in interviews with TBIJ, care workers described experiencing wage theft, paying up to £30,000 in illegal recruitment fees, receiving fewer hours than promised, and even being left destitute because of the working conditions experienced in the care sector.

While some of these issues have been raised by campaign groups and in the media, one key factor that came up again and again has received less attention: that workers feel trapped in these situations because their visa arrangements penalise whistleblowing.

The Bureau newsletter

Subscribe to the Bureau newsletter, and hear when our next story breaks.

Workers depend on their employer for the right to stay and work in the UK; losing their job for any reason means they have, at most, 60 days to find a new work sponsor or leave the UK, once they are contacted by the Home Office. Some also live in housing provided by their employers, which they can lose if they leave their job or are dismissed. All of this, experts say, leaves them at greater risk of exploitation.

About a third (30%) of those who have been mistreated at work said they were scared to raise concerns about their manager or employer because they feared reprisals, including losing their work and visa, and threats to their safety.

It has left some migrant workers in horrific circumstances.

Abena*, who had come to the UK from southern Africa, told Citizens Advice she had been raped by her boss, the manager of a care home, on several occasions, including while on an overnight training course.

She attended a rape crisis centre but decided not to go to the police. She told her manager she wanted their relationship to remain purely professional, and thinks that he punished her as a result by not giving her any shifts.

Bernice* lived in housing arranged by her employer while working as a carer. She told Citizens Advice she had been sexually harassed by her landlord. Again, fear of losing her job had stopped her raising a complaint. A clause in her contract said that if she was sacked or resigned she would have to repay the cost of her flights to the UK.

“If she is dismissed she will have nothing – she will have nowhere to live, no money, no right to access public funds, no sponsored work visa, and will have her final months’ wages taken off her,” noted the call handler.

A Home Office spokesperson told TBIJ: “We strongly condemn offering health and care worker visa holders employment under false pretences and will not tolerate illegal activity in the labour market.

“We are committed to stamping out exploitation of those working in the care sector and have announced providers in England will only be able to sponsor migrant workers if they are undertaking activities regulated by the Care Quality Commission.”

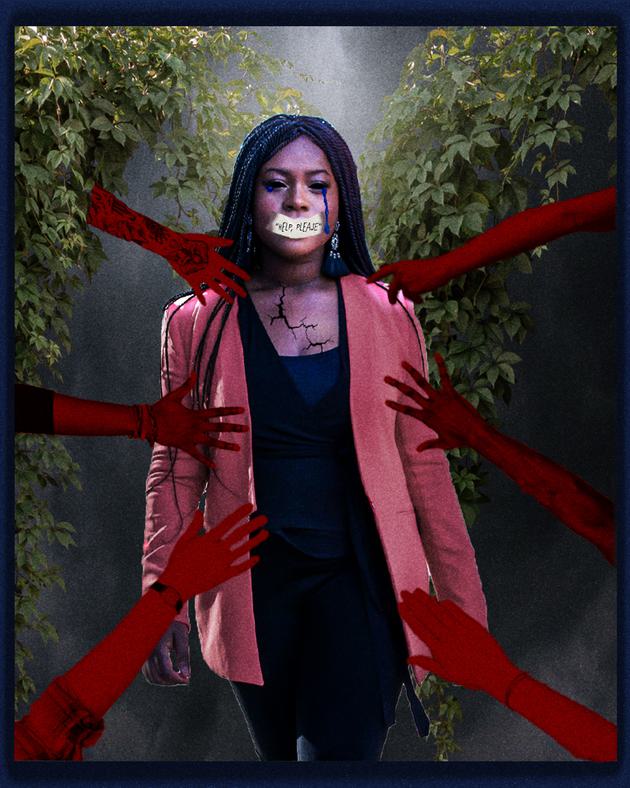

Illustrations: Aba Marful (Morganite)

Illustrations: Aba Marful (Morganite)

‘A modern slave trade’

The latest government figures show almost 106,000 visas were granted to care workers in 2023 – a number that has trebled from the same period in 2022. People from India, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Ghana, Bangladesh and Pakistan topped the list of nationalities travelling to the UK to plug the labour gap.

To get the visa, a person must have a job offer from an approved UK employer, also known as a sponsor. The worker remains tied to their sponsor for the length of their visa. This places employers in an “incredible position of power”, said Dora-Olivia Vicol, chief executive of the Work Rights Centre, an organisation that supports migrant workers.

“What the Home Office and labour enforcement agencies need to realise is that, in the current conditions, people don’t report exploitation because they don’t want it to backfire,” she said.

“Employment justice is a public good and you have these rogue employers operating unlawfully in the knowledge that no one’s going to check and then no one’s going to say anything because it will hurt them.”

Few of the workers who spoke to Citizens Advice or TBIJ said they would be willing to blow the whistle on their sponsor. Demi*, a live-in care worker, said she was terrified about the financial power her agency has over her.

She was sometimes expected to work 20 hours a day, without rest breaks or time to recuperate between placements. But her complaints went nowhere, and her mental health suffered. “If I keep going like this, I won’t survive,” she said.

“I’m not sure how care companies in a first-world country are capable of getting away with abuse, exploitation and, simply put, a modern slave trade.”

In another case, a Nigerian worker who complained about earning below the minimum wage was told he would have to move more than 300 miles for a different placement. The employer revoked their sponsorship because he refused.

Power imbalance

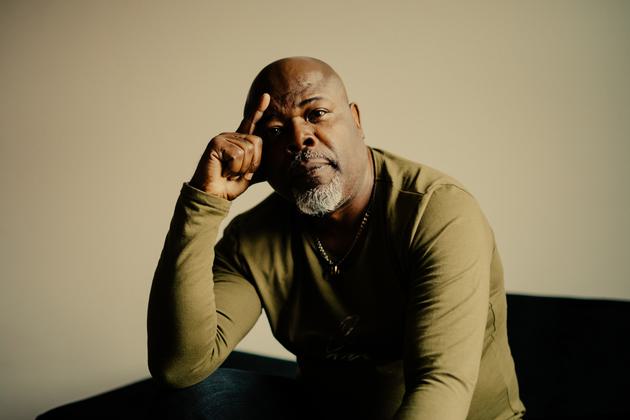

Neville returned to Jamaica in November of last year after being dismissed from his job at a large care home in Torquay.

He felt the decision was unjust, but couldn’t bring an unfair dismissal claim because he hadn’t worked at the home for the necessary two years.

Instead of supporting residents, Neville, 60, and other migrant workers were initially made to work as cleaners and kitchen porters. “It was terrible,” he said. “I didn’t come here for that.”

Neville (who asked for his surname not to be published) was also renting his housing from his employer. A month into his stay, he and the other tenants, who were also migrants, were told they would have to share their single rooms. Seventeen people were living in the property, Neville said.

Neville had to return to Jamaica when he was unable to find a sponsor

Peter Flude

Neville had to return to Jamaica when he was unable to find a sponsor

Peter Flude

He refused to share, so his room was changed while he was at work. “They’re telling us every day that we are to maintain residents’ dignity,” he said, “but what about ours?”

Unable to find another sponsor, he had to move out and ultimately returned to Jamaica. Neville said he was fearful of whistleblowing while in the UK because of the power imbalance between him and his employer.

No protections

Aké Achi founded the charity Migrants at Work, which scrutinises the intersection between immigration law, employment law and human rights. He told TBIJ that immigration rules penalise whistleblowers, adding that they need to be protected from the Home Office as well as their employers.

It is unlawful for an employer to dismiss someone, make them redundant or force them to resign after whistleblowing, but Achi said they often do.

In fact, reporting can directly put their own and their colleagues’ jobs at risk, if the Home Office responds to allegations by revoking the company’s sponsorship licence.

Achi said: “[Workers] have to make a choice between either remaining in exploitation or reporting a sponsor to deal with their own problem, but at the same time, it potentially will affect those who have stayed behind.”

Achi said he knew of care workers who had cooperated with Home Office investigations only to lose their jobs and be given no support to gain new employment. In other cases they were identified to their employer, something that could both jeopardise their safety and lead to them being shunned by their community.

He said one solution would be to ensure that protections for whistleblowers are inserted into immigration rules.

In one case in our investigation, a Filipino worker travelled to the UK to be a carer only to find herself working at an assisted living home for prisoners. Feeling unsafe, she quit, but her employer argued she was in breach of contract and tried to make her return to work. She told Citizens Advice she was worried that reporting the company would cause problems for other Filipino employees.

In the end she did contact the Home Office, who told her she could seek alternative employment, but did not take action against the company.

Finding a new job, however, is not always easy. The charity Skills for Care estimates there were approximately 152,000 vacancies in adult social care in 2022-23. Despite this, overseas workers who lose their jobs while in the UK can struggle to find new care companies to sponsor them. Some are refused references; others have unfair clawback clauses in their contracts that kick in if they quit. Citizens Advice spoke to one person whose employer said they would have to pay back £11,500 if they left the company within five years.

Nowhere to turn

Eshan* paid a recruitment agency in his home country, India, almost £17,000 before coming to the UK in April 2023 to work in care.

He was promised 40 hours of work a week with Swan Care Solutions, and in return he completed online training and bought a car that he needed for the job. But soon after he arrived, he visited the company’s offices and felt something was wrong.

The office, in Wolverhampton, was bare inside, the size of a single bedroom, and there was just one staff member present. Eshan saw no company signs or branding.

In the months that followed, Eshan claims he received no work or pay. He says his emails to management went unanswered. He has filed a claim with the employment tribunal that includes unpaid wages and unlawful recruitment fees.

He also complained to the Home Office and Care Quality Commission (CQC), the independent regulator for health and social care, but said neither authority replied. Swan Care Solutions is still registered to sponsor overseas care workers.

Elizabeth Chengeta, managing director of Swan Care Solutions, denied the allegations but said she could not comment further as it is an ongoing legal case. She says that the company has multiple offices which have had visits from commissioners, councils and CQC and no concerns about the office have previously been raised.

“I went through a depression and I didn’t know what to do,” said Eshan. “I was sitting inside my room [by myself] … Everyone thought that I was doing my work but there’s nothing happening.”

“Everywhere in the UK it’s happening nowadays, with the same thing that I am facing.”

Pursuing employment tribunal claims present many challenges for migrant workers. Legal aid is not available for the vast majority of employment matters, including unlawful deduction of wages, unfair dismissal and breach of contract.

Of the 172 migrant care workers TBIJ and Citizens Advice spoke to, only six are known to have escalated their case to an employment tribunal. Solicitors have to work at the intersection of immigration law and employment law, making it a “hugely complex area of advice,” said Vicol of the Work Rights Centre, which is supporting Eshan.

Licences revoked

TBIJ can also reveal that 55 care providers that were granted sponsor licences have had employment tribunal judgments made against them since November 2017.

The Home Office publishes a list of all visa sponsors but does not make clear which of them are care providers – so TBIJ cross-referenced the register with the Care Quality Commission’s list of service providers and the employment tribunal decisions database.

The government’s guidance for visa sponsors prohibits companies that have breached immigration law, but has no such restrictions regarding employment law. The Home Office told TBIJ it could not assess whether sponsors had broken employment law because it was not a labour market regulator.

Between August 2020 – when the health and care worker visa was launched – and March 2024, the number of care providers with visa sponsorship licences ballooned from just over 250 to more than 3,200. In that time, nearly 200 have been removed from the Home Office register.

TBIJ has been unable to establish with the Home Office why those providers had their licences revoked. Experts said having this information would be crucial for the adult social care sector, especially if they are to help migrant care workers before they hit crisis point.

Half of the migrant care workers who contacted Citizens Advice were facing financial hardship by the time they made the call. Many only asked for help once they were already in debt and unable to pay for food, rent and other bills. Because of a visa condition known as “no recourse to public funds”, they could not claim most benefits or help with housing.

Even Citizens Advice staff struggled to support them. Helen Brown, an advisor with Citizens Advice Shropshire since 2021, told TBIJ: “It was a whole learning curve of stuff we hadn’t interacted with before... At one point I remember thinking, ‘Oh, we can’t give them food bank vouchers’ and then having to ask around the office if it’s allowed because we didn’t know. Fortunately, it is, but it still feels like the bare minimum as to what we can offer them.”

Brown said she and other advisors find themselves “stuck in a catch-22”. She wants justice in cases of mistreatment as much as the callers do, but reporting an employer to the Home Office carries a huge risk: that the worker will lose their job and have limited time to find a new sponsor.

“This is such an open loophole that if you’re dismissed for whatever reason – if you’re exercising your employee rights to join a trade union or complain about racial discrimination – you can be dismissed, and that has no bearing on the Home Office’s decision. You have 60 days. That’s not enough time to go to an employment tribunal at all. That’s not enough time to take any action and then also find a sponsor.”

She described one case in which several migrant workers at a company were not being paid but their white British colleagues were. All she could offer were food bank referrals or help with energy bills, and it left her feeling hopeless. “I did end up crying,” she said. “I just couldn’t do it.”

*Names have been changed to protect sources.

This article was amended on 12 March 2024 to clarify a reported quotation

Reporters: Vicky Gayle, Emiliano Mellino, Hajar Meddah and Charles Boutaud

Bureau Local editor: Gareth Davies

Deputy editors: Katie Mark and Chrissie Giles

Editor: Franz Wild

Production editors: Frankie Goodway and Alex Hess

Fact checkers: Lucy Nash and Chrissie Giles

Illustrations: Aba Marful (Morganite)

Photography: Peter Flude

Our reporting on insecure work is supported by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and is part of our Bureau Local project, which has many funders. None of our funders have any influence over our editorial decisions or output.

-

Subject:

-

Area: