I went to Pakistan to see the cost of a superbug crisis

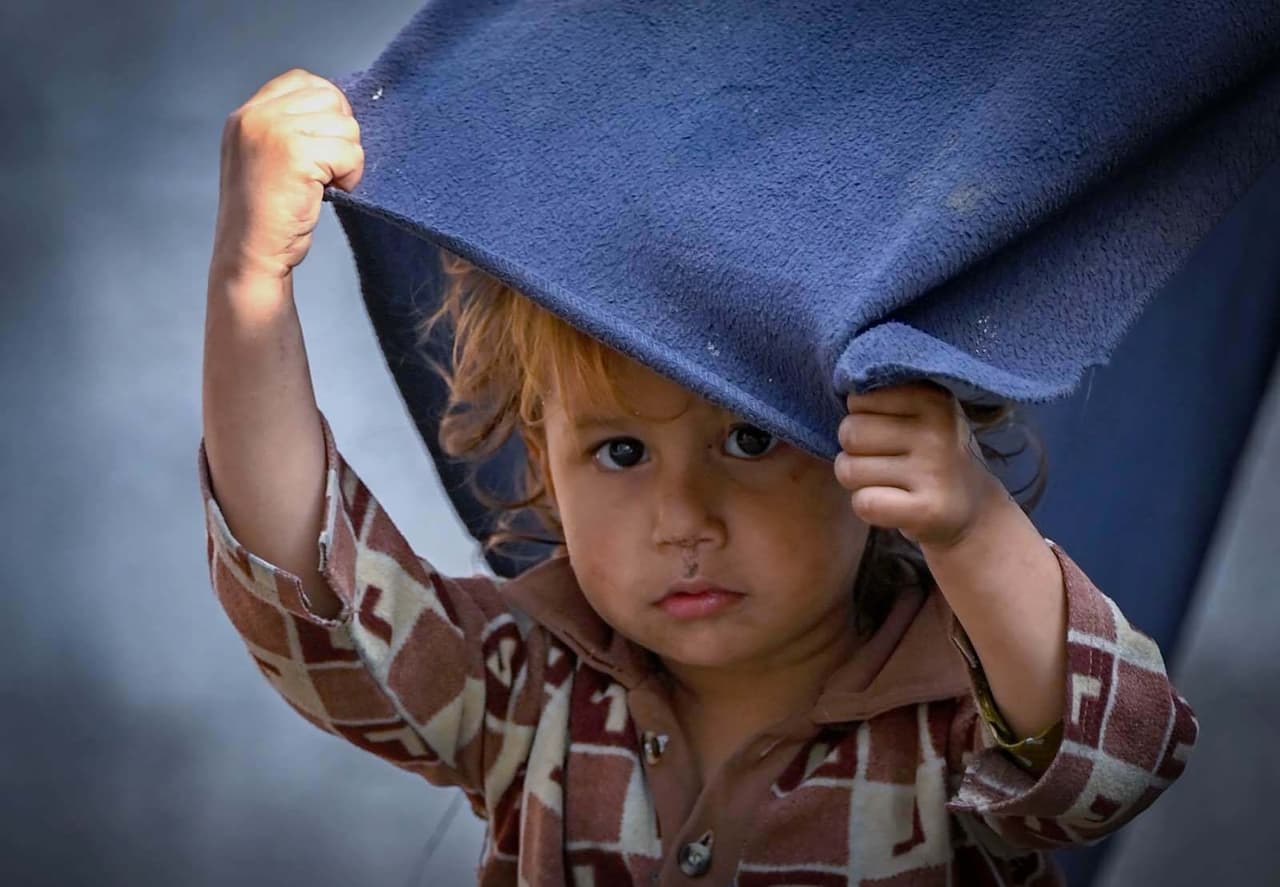

In a neglected part of Peshawar, north Pakistan, a decades-old refugee settlement has woven itself into the fabric of the city. People have fled here from Afghanistan over years of turbulence.

At the gate of one home, I left my photographer and a doctor at the threshold and went in alone. All of the women who lived there were sick, and preferred not to have men they didn't know inside their home.

I’d come to the city to try to grasp the spread of drug-resistant infections in the area. All three women I spoke to had been ill for some time. Two had fevers and coughs that had been going on for months, while another had a vaginal infection she was too embarrassed to get checked. One of them had managed to get hold of cefixime, an antibiotic reserved for severe infections, from a free healthcare clinic. But she didn’t know how many tablets she had to take or for how long.

With no instructions, these women are likely to overuse or misuse drugs that require careful control. This behaviour risks making the bacteria that the drugs were intended to kill stronger as they transform and multiply. And these become the superbugs that are posing a challenge to healthcare systems around the world. On top of the 1.27m yearly deaths attributed to antibiotic resistance, millions of other people around the world are living with drug-resistant infections.

If these numbers are shocking, then the human stories behind them are even more so. I spent three weeks in Pakistan looking into this growing global threat, seeing how superbugs are created, and the devastation they leave behind. I expected it would be difficult finding patients, but in some areas it felt like that behind every door I knocked on there was someone with an infection that even the strongest antibiotics weren’t curing. Everywhere I went, it was clear that the poorest were suffering the most.

Drug-resistant infections are a threat for all countries, no matter their wealth, and their spread is not confined by country borders. In the next few months, before a vital meeting on the topic at the United Nations general assembly in September next year, TBIJ will be reporting from the frontlines of this existential threat.

In Pakistan, the living conditions in poor settlements are a breeding ground for disease. In many places I visited, there were no sewers or refuse collection and limited access to clean water. The narrow pathways separating the homes were littered with rubbish and sometimes faeces. Animals and humans lived in the same compound.

In one household I visited, several family members, both young and old, were suffering from a diphtheria outbreak. The antibiotics they had taken weren’t working – the bacteria causing the disease were drug-resistant, according to the local doctor. With the family only able to afford treatment for one person, their youngest baby was prioritised while the rest lived on with their fevers, coughs and fatigue, often for months at a time.

Yet that sought-after treatment is also part of the problem. From what I saw, the way antibiotics are being prescribed in the country flies in the face of all of the advice issued by global health organisations. Time and again I saw antibiotics meant to be used for only the most resistant infections being issued without any tests on the patient. These drugs were available over the counter at most drug stores and were prescribed unnecessarily by physicians.

The Naguman settlement in Peshawar, in northern Pakistan

Abdul Majeed

The Naguman settlement in Peshawar, in northern Pakistan

Abdul Majeed

In the south of the country, in a fishing village on the outskirts of Karachi, I saw more restless parents with fever-ridden children. The main hospital in the area was under-resourced, and the unregulated clinics nearby often prescribed antibiotics. These prescriptions were then taken to the adjoining drug outlets that had teenagers at the counter, rather than qualified professionals.

Back in Peshawar, a doctor from a charity-run clinic next to the refugee settlement is still sending me details of cases he suspects are drug-resistant. He says many of the patients no longer respond to the treatment that could have once cured them. Instead they’ve been suffering for months with pneumonia, typhoid or diphtheria.

But even vigilant doctors like him can contribute to the problem. His clinic runs on donations and lacks the resources to manage patient records, so many of the treatments given there go unmonitored. That’s yet another aggravating factor in the spread of superbugs.

Over the next few months we will be investigating the factors contributing to this global health threat, what it’s like living with the consequences of drug-resistant infections, and what we can do now to stop superbugs in their tracks.

Header image: A young girl in Peshawar, north Pakistan

Reporters: Misbah Khan

Global Health editor: Fiona Walker

Deputy editors: Chrissie Giles and Katie Mark

Editor: Franz Wild

Production editor: Frankie Goodway

Fact checker: Billie Gay Jackson

Photography: Abdul Majeed for TBIJ and the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy

Our reporting on superbugs and antibiotic resistance is funded by the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. None of our funders have any influence over our editorial decisions or output.

-

Area:

-

Subject: