Revealed: escalating effects of hot summers on UK housing

TBIJ carried out a groundbreaking community project to show the impact of climate change on south London residents

An air cooler with built-in ice packs may sound like a novelty Christmas present, but for Latoya the joke has a serious side. She needs new ways to keep cool in her flat in Peckham, south-east London, because each summer it gets so hot she experiences nosebleeds and migraines that make her throw up.

Latoya is pre-diabetic and suffers neurological issues, which keeps her at home much of the time. During the summer months she likens her flat to a “furnace”; it is a struggle to sleep, work and cook for herself and her children.

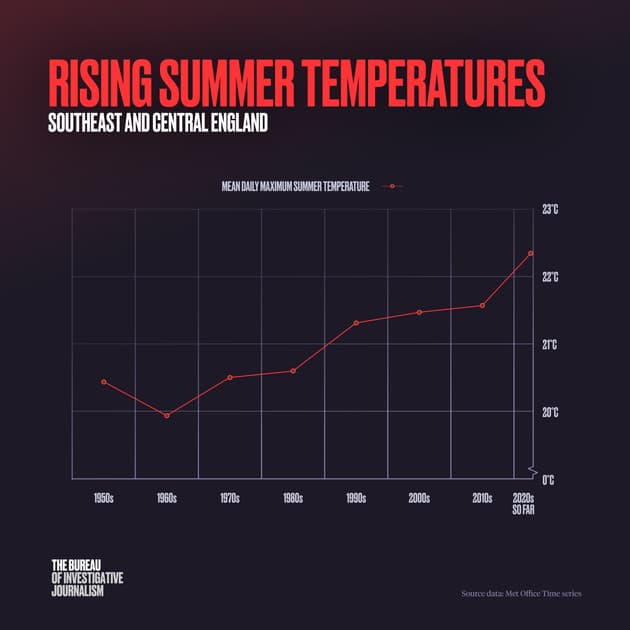

She’s not alone. The UK may not have a reputation as a hot country but temperatures are rising because of the climate crisis and experts say its housing is not designed to cope. And tomorrow, world leaders gather in Dubai to discuss global climate issues to do with urbanisation and the built environment.

In 2019, the UK’s Climate Change Committee warned that homes in the UK “are not fit for the future” and that attempts to adapt housing stock for higher temperatures are “falling far behind the increase in risk from the changing climate”. But there has been little data gathered to show how people experience heat in their homes.

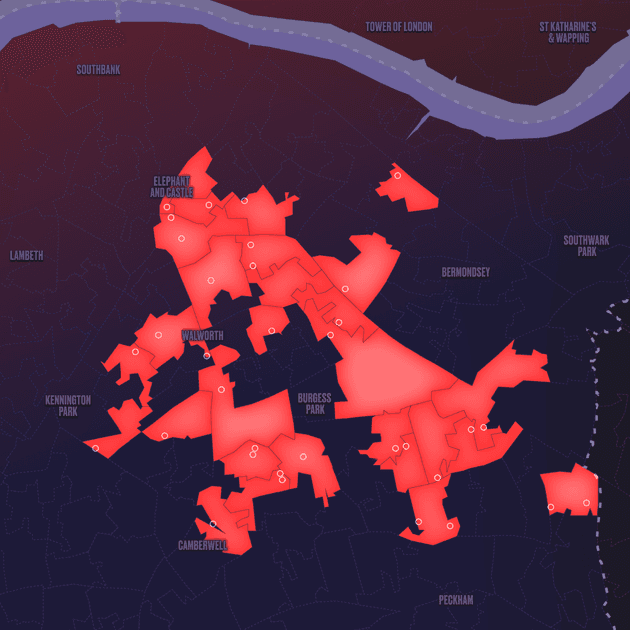

To address this research gap, the Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ) partnered with the University of Glasgow’s Urban Big Data Centre to launch our Hot Homes project. We installed sensors in 40 homes in the London Borough of Southwark – one of the hottest places in the UK, according to our analysis of Met Office data – to measure heat, humidity and air quality from early August to mid-September this summer.

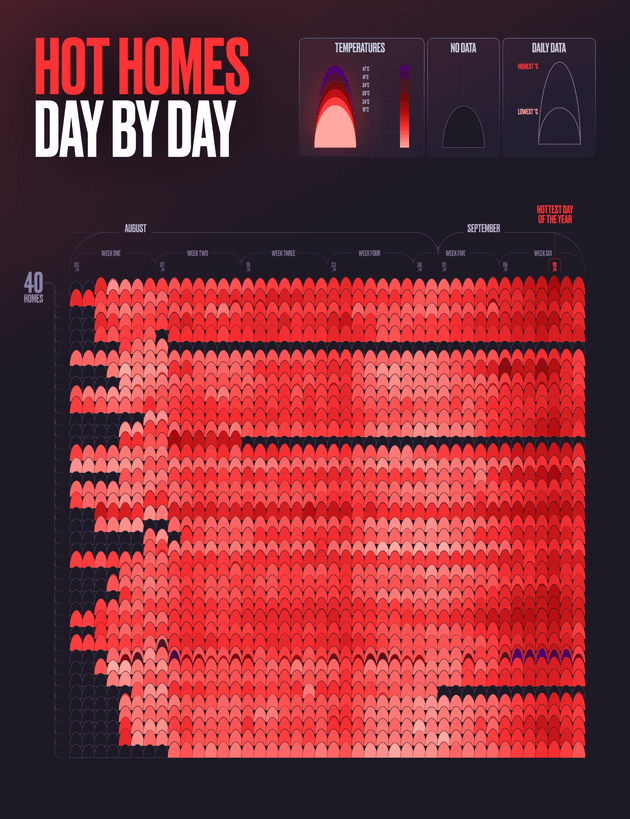

The results were striking. During the monitoring period, every home in the study rose to at least 25C, the maximum indoor temperature for London recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). And this was despite relatively cool weather in July and August.

The data was recorded by sensors, mostly placed in bedrooms. Some homes were as much as 8-10C hotter at night than the outdoor temperatures recorded at the local weather station. Five people who participated described their home feeling like a sauna and three described their home feeling like a “greenhouse”. Others used the terms “heat chamber” and “oven”.

Many of those who took part also experienced sustained heat, with homes remaining hot overnight and not allowing occupants a chance to cool down. According to the WHO, extended periods of high temperatures “create cumulative physiological stress on the human body, which exacerbates the top causes of death globally”.

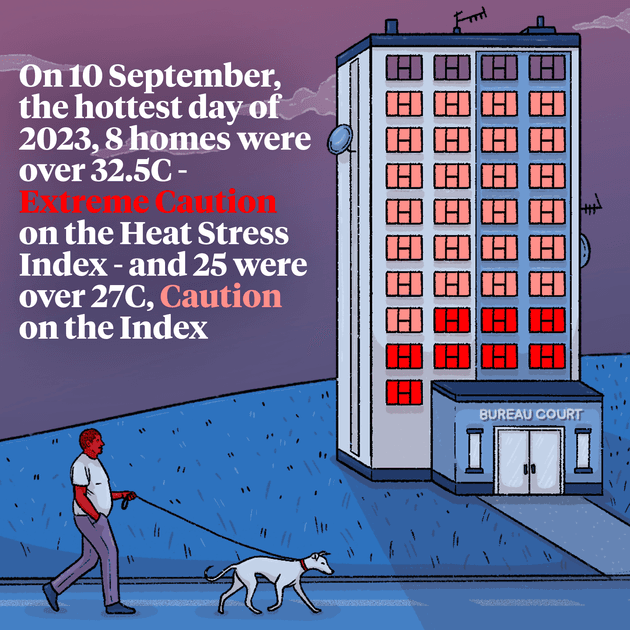

TBIJ also used the Heat Stress Index, a model that factors in relative humidity to determine how temperatures are likely to feel. By this measure, almost all the homes in the study experienced conditions that felt like 27C (classified as “caution” in the Heat Stress Index, carrying the danger of fatigue), and 12 households experienced conditions that felt like 32.5C (classified as “extreme caution” and carrying the dangers of heat exhaustion or even heatstroke).

Dr Qunshan Zhao, senior lecturer in urban analytics at the University of Glasgow, said that while heat has not historically been a major problem in the UK, it is now becoming an “upcoming and urgent issue”.

“I think the most surprising part of this analysis is how many households experience indoor heat stress in London,” he said.

The temperatures recorded in Latoya’s home were among the highest in the study. The flat she rents from Southwark council is a newbuild, well insulated and warm in winter. But that insulation also prevents her flat from cooling down in the summer: temperatures in her home stayed above the WHO’s recommended level for an unbroken period of over two weeks this year.

“It was interesting to find out that both older homes with low energy efficiency and newer builds with high energy efficiency end up being hot,” said Dr Zhao.

But while high-end newbuilds can be as vulnerable to high temperatures as older and less expensive housing, a person’s financial conditions can still be a huge factor in how they experience the consequences. Not everyone can afford an air conditioning unit, for example.

And if you can’t, research suggests you could suffer. It has been shown the death rate increases more rapidly per degree as temperatures rise above 27C.

Among our participants were people who had existing health conditions – such as respiratory issues and autoimmune disorders – that were exacerbated by the heat. At least two people attended A&E during the monitoring period following the heat, another had to go to their GP and a specialist clinic, and several others had to use extra medication. Many participants said they or their family members had trouble breathing at home at some point during the summer. The son of one participant has a congenital heart condition, and said that he felt faint and dizzy, as if he had heatstroke.

During the heatwave week this September, the longest run of days above 30C on record in the UK, the NHS put out a press release to highlight the number of people visiting its site for advice on heat exhaustion, with 32,130 visitors in just five days. One day saw a visitor every eight seconds.

Professor Anna Mavrogianni, a heat and housing expert from the University College London’s Institute for Environmental Design and Engineering, said TBIJ’s findings “clearly indicate that overheating in London homes is not a future but a current and ongoing problem, in particular in more energy efficient, newly built constructions, which will be exacerbated as our climate becomes warmer”.

“Prolonged exposure to high indoor temperatures, especially when there is no night-time respite from heat, can result in a range of adverse health effects, especially for the most vulnerable populations groups – such as babies and young children, and older people or people suffering from cardiovascular, respiratory or mental health conditions,” she said.

With regard to the structural problems, almost 70% of our participants said ventilation issues were causing their homes to overheat, while 71% said that lack of shade was a major factor.

Another aggravating factor is communal heating systems, or district heating: networks of pipes that deliver hot water and heat to individual properties, and which residents often cannot switch off. Our study found the homes affected by these systems to be more than 1C hotter on average this summer than those without.

Adaptations to buildings and infrastructure are, however, becoming an increasing policy focus. Building regulations in England were amended last year to include the requirement that new building projects consider the potential for overheating.

Westminster’s environmental audit committee is also carrying out an inquiry into heat resilience, sustainable cooling and the relationship between heat and health, which is due to report soon.

Explore the full dataset from our Hot Homes project

Click hereAcross London, any developments of 10 or more homes funded through the mayor’s affordable homes programme will be required to develop an energy strategy to reduce the potential for overheating. Any home with three or more bedrooms will have to be designed to improve ventilation and reduce overheating.

The mayor’s office has also commissioned an independent review into the city’s ability to adapt and respond to the climate crisis, which is expected to report back in early 2024.

And Southwark council has consulted on its own climate adaptation plan, also set to be published early next year.

Councillor James McAsh, cabinet member for the climate emergency, clean air and streets, says Southwark’s adaptation strategy “includes plans to build resilience to overheating, by cooling buildings, providing respite from heat and preparing for extreme temperatures”.

“We also recently held a consultation, which will be strengthened by the Hot Homes study, to help deepen our understanding of the issue of overheating within homes in the borough.

“[But] achieving our targets requires the government to step up. Buildings are central to this challenge, so we need the government to develop and fund a retrofit plan that improves the energy efficiency of housing across the country while also ensuring issues such as overheating are addressed.”

A government consultation carried out in 2021 concluded the risks to health, wellbeing and productivity due to overheating homes should not be ignored – and “neither can the potential loss of life that may occur if action isn’t taken”.

The media landscape also plays a role, according to Chloe Brimicombe, of the Wegener Center for Climate and Global Change at the University of Graz.

“It’s well documented that the narrative around hot summers in the UK are ones of beach holidays and ‘fun in the sun’, or it’s characterised almost as an achievement that records have been broken,” she said.

“The lack of stories and evidence of the impact of heat in the UK makes it more difficult for the risk to be understood and this is a barrier for creating evidence-based policy.”

Olivia Gable, a 35-year-old social researcher from Texas, lives in a block of flats built in 2015. Her home is uncomfortably hot, she said, with the temperatures causing headaches, nausea and discomfort.

“I think it speaks to something bigger,” she said. “I don’t think the UK is doing enough to build for the hotter temperatures … but also to put infrastructure in place, and think about what really needs to change instead of just treating the symptoms.”

For her, policy changes can’t come soon enough. “The UK is not building to deal with what’s coming and to deal with what we’re already experiencing,” she believes. “There needs to be radical change in the way houses and flats are designed and built.”

Latoya hasn't formally complained about the heat in her home

Latoya hasn't formally complained about the heat in her home

In September, TBIJ hosted a community meet-up for the people who had taken part in the project, which included a discussion of how overheating should be addressed. One person said policy makers “should work with communities to identify low-cost solutions because people know their own neighbourhood best”.

Another highlighted the importance of being kept informed if adaptations are indeed being considered. At the moment, they said, “[it feels like] we should just get over it and manage”.

For now, Latoya is doing exactly that – trying to manage. She hasn’t formally complained about her flat as she feels everyone in her block is affected. And because she likes where she lives. It’s just that every year, she dreads the hot months. “I think I have to put up with the three months of summer to be comfortable the other nine months,” she says.

And the issue isn’t going anywhere. “The UK is hot,” says Latoya. “We’ve been hotter than the Caribbean [at times], hotter than Asia. It’s never been like that before.”

This project was supported by Google News Initiative, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Impact on Urban Health and Necessity

Reporters: Rachel Hamada, Dahaba Ali Hussen and Hajar Meddah

Glasgow University team: Qunshan Zhao, Mark Livingston, Congying Hu, Mingkang Wang

Additional reporting: Natalie Bloomer, Cherise Hamilton

Research methods associate: Alison Thwaites

Data lead: Charles Boutaud

Bureau Local editor: Gareth Davies

Deputy editors: Chrissie Giles and Katie Mark

Editor: Franz Wild

Data visualisation: Maral Pourzakemi

Illustrations: Nadia Akingbule

Photography: Alex Sturrock

Thanks to: Janet Gunter, Misbah Khan, Nyheke Lambert, Elisângela Mendonça, Emiliano Mellino and Lucy Nash