Behind every swipe: the workers toiling to keep dating apps safe

Harsh targets and distressing content have left mental scars on a global workforce of content moderators

Content warning: This story contains references to violence, abusive behaviour and suicide.

“I wasn’t able to go outside, anywhere alone … I had so much anxiety that when I went outside to do errands, I lost consciousness twice. That’s when I realised I was very sick.”

Ana* began working for LGBTQ+ dating app Grindr when she was in her early twenties. Her team was based in San Pedro Sula, Honduras’ second city, dealing with tasks ranging from the mundane (tech support emails, billing queries) to the horrifying: user reports of sexual assault, homophobic violence, child sexual abuse and murder.

As the months went by, her mental health began to spiral. Her illness made it difficult to look for other jobs, and she feared if she complained about her conditions she would struggle to find work at other outsourcing firms in Honduras. “I couldn't get out because I couldn't leave my job,” she said. “I couldn't fight for more. I didn't speak up.”

Ana had joined the Grindr team at an outsourcing company as an ambitious young graduate, ready to start her career. She left in 2019 with anxiety and depression, unable to work for months afterwards, and said she later received a PTSD diagnosis.

The conditions faced by moderators such as Ana – whose vital work helps remove abusers from dating apps – have left their scars not only on her but on an international workforce of staffers, outsourced employees and freelancers across the online dating industry.

TBIJ interviewed more than 40 current and former workers across Match Group – the conglomerate that owns Hinge and Tinder – Grindr and Bumble, based in Honduras, Mexico, Brazil, India, the Philippines, the US and the UK. The picture varied from one app to another and different allegations were made against different companies. But the trends were stark.

Many workers told of mental health issues including symptoms of anxiety, depression and PTSD that they associated with their jobs. One had attempted suicide on multiple occasions. Concerns were raised about understaffing, punishing productivity targets and a shortage of mental health support, as well as the time it took to address users’ abuse reports. A number of workers drew a direct link between their working conditions and the safety of the apps’ users.

Ana was one of hundreds of Hondurans hired by US-headquartered outsourcing company PartnerHero, which offers cut-price customer support and moderation services to companies such as Grindr, one of its biggest accounts. Most of its workers are based in Honduras and the Philippines, with a smaller team in Brazil. PartnerHero advertises these locations to global businesses as an opportunity for “substantial cost savings” on wages, recruitment, taxes and facilities. It also has smaller hubs in Berlin, Bucharest and Cape Town.

PartnerHero styles itself as a principled upstart setting right an outsourcing industry dogged by claims of worker exploitation and union-busting.

“Capitalism is failing,” said its outspoken founder and CEO Shervin Talieh in an interview with online magazine Authority last year. “We have to stop seeing employees as a cost […] They are not an integral piece of our success – they are the integral piece.”

However, PartnerHero workers interviewed by TBIJ said they faced distressing working conditions and received little support, with some penalised and even fired during mental health crises associated with their work.

PartnerHero told TBIJ that it is “committed to being at the forefront of employee welfare in our industry and equally committed to supporting our partners’ important missions and the safety of their users”.

Grindr told TBIJ: “We respect how difficult the role of a content moderator can be, and have worked in collaboration with PartnerHero over the course of our relationship to consistently improve processes, training, and support for the moderation team.”

The online dating industry reported revenues of around $2.6bn last year, while Bumble, Grindr and Match Group – the parent company of Hinge and Tinder – are worth a combined $13bn. But the industry has been dogged by criticism for the abuse, harassment and offline violence their users can face.

Less is known, however, about the global workforce tasked with moderating these platforms, often in precarious conditions thousands of miles away from dating app HQs. Many say the work left them traumatised.

A few hundred miles away from PartnerHero’s Grindr team, moderators at another outsourcing firm work through Hinge abuse reports. As of 2019, Hinge has been owned entirely by Match Group, the company that owns more than 45 online dating brands. Three years later it laid off the majority of its US-based moderators and replaced them with outsourced workers employed by Telus in Guatemala, paying them substantially lower wages. People who until recently held senior roles at Match Group voiced concerns to TBIJ that management appeared to have deprioritised user safety in pursuit of higher profits.

Match Group told TBIJ: “Safety is imperative to our business and our continuous efforts to enhance our features and policies in order to make our platforms safer for everyone will never stop.”

Until recently, Bumble relied heavily on remote freelancers including in Brazil, the UK and the Philippines to cover its routine moderation. Now, an outsourced team in India supplements an in-house team of specialists.

Gael, a freelancer who worked for Bumble from his home in Brazil until earlier this year, still struggles to discuss two cases of child sexual abuse he was tasked with reviewing. “It’s fucked up to actually speak about it, because it kind of brings back the image,” he said. “[Those cases] didn’t allow me to sleep well for a few weeks after.”

Gael felt he had not received adequate training to deal with such distressing images. “It’s like they expect for you to be smart and agile enough to handle these types of situations,” he said.

Bumble told TBIJ moderators are provided with clear and consistent enforcement guidelines and reporting requirements for different types of suspected abuse.

Users in danger

Dating app users may not realise that if they report another user for abusive behaviour such as harassment or sexual assault, it could be initially reviewed by an outsourced worker in Honduras, India or Guatemala. These people decide whether the user should be banned from the app and if the case should be “escalated” to staff safety specialists.

Recent headlines reveal the serious dangers dating app users face. “Disturbing Tinder messages killer sent Grace Millane before strangling her” reads one. “Police arrest sexual assault suspect who lured victims to his apartment via Grindr” reads another.

But as well as the salacious true-crime fodder, there are numerous instances of harassment, bigotry, drug-dealing and, in the case of Grindr, homophobic blackmail and violence.

Some of the workers interviewed for this piece expressed concerns about their ability to respond quickly and effectively to users’ reports of abuse.

An incorrect decision on an abuse report could have serious consequences. TBIJ reviewed one woman’s report of a sexual assault that occurred after a Hinge date, which was missed and left unanswered. Only when the woman chased it – a year later – did Hinge ban the user in question.

And the issue of moderators making errors was reported across multiple apps. “Sometimes we made mistakes that we were not accounting for, or [that] could have been avoided if we had more people,” said one former Grindr moderator.

While Bumble and Hinge deal with all escalated legal cases and law enforcement requests in-house, Grindr outsources some of this work to a legal sub-team in Honduras. One former worker said that although he received training when he moved onto this sub-team in 2019, he had no experience dealing with complex legal requests.

PartnerHero told TBIJ: “We have collaborated with Grindr to evolve processes and training.”

‘You’re supposed to respond like a robot’

Laura worked on escalated cases, including assault, as a Bumble staffer in the UK before she left in 2022. She described “a huge backlog” of these serious cases, which she ascribed to “chronic understaffing”.

“There were not enough people to cover the quantity of stuff that was happening,” she said, “so rather than hiring more people they put more pressure on us to get higher numbers.”

Bumble says it aims to resolve all reports within 48 hours. However Laura said wait times were often far longer, sometimes leaving even the most serious cases unanswered for weeks. Backlogs of dating app tickets are likely to lead to delays in dealing with serious issues, two sources said.

Bumble told TBIJ that it has increased its Trust & Safety team considerably since 2021 and that its member safety team has grown year over year. However it would not give specific headcount figures and did not say whether these teams included outsourced workers.

Bumble staff work through “queues” of reports, Laura explained, and its system was colour coded. “If you were within the [target] everything was in grey, or if it was getting to be bad it was orange, or if it was really bad it was red … And basically it was always red, all the time.”

As workers left, the number of Bumble’s member safety specialists, who investigate more complex cases including assault, racism and harassment, fell from 15 people to a low of seven in spring 2023, according to one former worker, though Bumble has recently begun hiring to fill the gaps.

“We were seeing a tonne of issues with various cases sitting in our queues for multiple weeks before any action was taken,” said one staff member. “The team was feeling really overwhelmed with the backlog that had built up and feeling like you would catch something super serious way too late.”

Bumble said it has never reduced the overall headcount of the member safety team but would not specify its current size. It said it had experienced delays when onboarding its new outsourced team but these had been reduced following “significant additional investment”.

Several of PartnerHero’s Grindr workers also expressed concerns about large backlogs. While some said they were usually able to clear them quickly, staff who worked on other unrelated teams at PartnerHero described being drafted in to help out.

Gruelling targets

Workers for Grindr, Bumble and Hinge said they were subject to unreasonable targets, with one at Bumble suggesting these were intended to plug gaps in capacity. Moderators were sometimes expected to make complex decisions about whether a user should be banned from the platform in a minute or less.

In his blog on the PartnerHero website, Shervin Talieh describes company culture as “an instrument for societal transformation” and says work has the power to “shape people and communities”.

“Does their work lift them, does it nourish them, does it allow them space to become a better version of themselves?” he writes, before bemoaning the tyranny of metrics and “productivity-obsessed managers” at other companies.

One PartnerHero worker, Ana, said the company tried to fire her when she became unable to meet her productivity targets, despite the fact that she was seriously ill. She eventually received a severance payment equivalent to five months’ pay.

Workers on Grindr’s PartnerHero team also had to maintain a personal “quality score” – a measure of their decision-making – of at least 92%. Three workers who left PartnerHero in 2023 said they felt they had been unfairly penalised or had their contracts terminated after changes in the way they were assessed.

Until mid-2021, Hinge also employed a team of moderators based in the US. They received an hourly rate of $20-30 and were able to access the company’s health insurance scheme.

According to an onboarding document seen by TBIJ, moderators were initially expected to process 35 profiles per hour, or a decision every 100 seconds. In July 2020, workers complained that this had been significantly increased, to 52 profiles per hour.

“We were getting graded every week on our performance,” said one former Hinge moderator. “And if you got below 85 [percent] or some high number, you could be fired. So it was just a volatile environment to be in, and when the quota went up, you had more chances of getting things wrong.”

At Bumble, Gael received a base rate of €10 an hour – a very good wage when converted into Brazilian reals, he said – but freelancers in other countries received a piece rate of between 3p and 7p per report processed. The variation in pay was based on their performance on sample cases where moderators’ answers were compared to those of a manager.

Dealing with cases of misogyny, transphobia and “general vileness” all day was stressful, said Oscar, a former Bumble freelancer based in Latin America. “Not to mention the stress of having to be correct on your test cases, or else I got paid even less.”

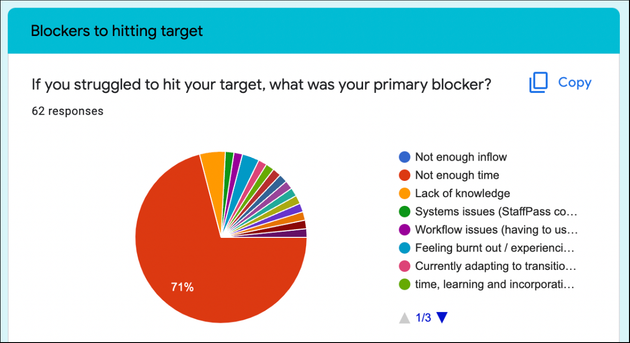

Management has also tried to impose stricter targets on specialists who worked on more complex cases but rolled back the plans after a backlash. TBIJ reviewed anonymous feedback collected by Bumble management after introducing these new targets, which included the comment: “Feeling burnt out and exhausted from always failing at my targets/falling short of my goals. Has me constantly feeling anxious.”

The same survey also asked workers: “If you struggled to hit your target, what was your primary blocker?” The most common reason, cited in 71% of responses, was “not enough time”.

Some of the results collected by Bumble's internal survey

Some of the results collected by Bumble's internal survey

“Rigid targets aren’t appropriate for the kind of work we do because we experience a lot of secondary trauma," said Laura, a safety specialist. “It could be like someone’s just poured their whole heart out to you, talking about some really traumatic experiences that they’ve gone through, like assault… and you're supposed to respond to it like you’re a robot.”

Laura was one of a number of workers interviewed who voiced concerns over user safety. “When it came to keeping members safe, it wasn’t really the policies as such that were the problem, it was more to do with the execution,” she said. “Because we were understaffed, people could be waiting days or weeks to have their reports seen.”

“And if [it was] for something serious, that means that person who’s been reported may have been on the app for all that extra time.”

Bumble told TBIJ that tough safety standards are “part of our values”.

Too much to bear

“We had three people just leave that day … because they could not handle it,” said one of Grindr’s Honduras-based workers, recalling a time when a number of colleagues had been exposed to images of child sexual abuse attached to an email from a user.

Ale and other workers who were hired before 2020 were usually recruited into a generic customer support role whose work could involve content moderation and other user safety tasks. Since then, roles on PartnerHero’s Grindr team have become more specialised.

Of the 14 former Grindr moderators TBIJ spoke to, virtually all testified to the traumatic conditions they faced. Some said symptoms of distress were widely evident among staff. One told TBIJ they had attempted suicide multiple times during and after their time at the company.

PartnerHero began working with Grindr in 2017, and the workers it hired were initially recruited into generic customer support roles. While they were always required to perform tasks related to user safety, over time PartnerHero took on the bulk of Grindr’s content moderation.

"Everyone’s emotions, at some point, started to leak into the air,” said one former moderator. “People were able to feel it … they noticed the tension, the hostile environment. It was awful.”

This tension was reinforced by the claustrophobic layout of the Grindr office, according to Hector, another former moderator. The floor was open plan and contained people working for different apps and campaigns, he said, but Grindr was in a separate office within an enclosed space.

“I don’t think we ever felt like part of it all. We were the spooky, weird guys that worked for this weird thing that nobody was supposed to see.”

Workers at Grindr and Bumble said they had to fight hard for their entitlement to mental health benefits. These varied significantly depending on the app and the contractual status of the moderator, and staff members tended to get better support than freelancers and outsourced workers.

Grindr workers at PartnerHero say that despite their repeated requests, there was little mental health support available to Honduran staff until 2020, when a third party was contracted to provide therapy, and subsidised mental health support was added to the company’s health insurance scheme. However, several workers who worked for PartnerHero after these benefits were introduced said they were not aware they existed.

Before this, said members of the Grindr team, they were told they could speak to a member of the HR department.

“This person had just graduated from a psychology major, they had no experience providing therapy,” Ale said, “and certainly no experience with things as sensitive as PTSD.” Ale, who had pre-existing mental health issues, was one of several workers who paid for their own private treatment to deal with work-related issues.

Grindr workers continued to lobby management for more mental health support and, last November, PartnerHero hired a staff wellness coordinator with a background in clinical psychology.

One recent Grindr worker who had accessed PartnerHero’s wellness programme described it as “worthless”. He said: “You call them, and they go through … the same questions like ‘How do you feel?’, ‘Can you just disconnect yourself for a moment?’, ‘Take a deep breath’, ‘Can you ask for a day off?’, ‘Can you talk to your supervisor?’. That’s it.”

PartnerHero told TBIJ that everyone on its Grindr team in Honduras receives medical and mental health plans and access to an employee assistance programme, with enhanced offerings for moderators.

Grindr management in the US has also previously rejected proposals for improved mental health support – with one option to include contractors – that had been drawn up with a consultancy focusing on mental health at tech companies.

At Bumble, workers were able to access mental health support through a private health insurance scheme and an employee assistance programme. In 2022, it expanded its offer, introducing a “wellness stipend” that could be used to expense therapy sessions or other healthcare and hiring a wellness liaison, who is trained to offer mental health support to employees.

“I think that was quite hard won,” said Laura, who used the wellness stipend to pay for therapy. “There were people who were there before me who’d been fighting for that for years and it hadn’t happened.”

Bumble told TBIJ it has expanded its mental health and wellness offerings to address and prevent the negative effects the work has on its staff specialists.

However, these benefits were not available to freelancers dealing with traumatic content like Gael and Oscar.

The Bureau newsletter

Subscribe to the Bureau newsletter, and hear when our next story breaks.

At Hinge, one moderator said there were facilitated group and individual sessions with a therapist that they could attend to talk through some of their issues.

Charlotte said these were a useful “support group” where people could talk over workplace issues. She said it initially felt like a “safe space” for workers to discuss these topics without risking their jobs, but said “once we started voicing our concerns, you could tell that there was unrest on the management side”.

Going global

Until 2021, Hinge directly employed a team of around 15 US-based moderators. But when these workers raised concerns about unmanageable new targets in July 2020, a senior staff member threatened to “dissolve” the team and go offshore, or take away their benefits.

It was not an empty threat. A year later moderators were called into a Zoom meeting and told they were being laid off, effective immediately. The meeting lasted seven minutes, with no opportunity for questions. Two workers said they eventually received $10,000 severance before tax.

As of mid-2022, there were just seven moderation and appeals specialists on staff in the US, with 43 agents who had been hired at outsourcing firm Telus International in Guatemala, to cover the app’s 6 million estimated monthly users. This meant Hinge could now pay a Guatemalan worker a quarter of a US moderator’s salary.

“The whole idea was that Hinge was doing moderation differently,” read one message sent on a moderators’ WhatsApp group shortly after the layoffs were announced. “We were an in-house experiment. And now they’re going back out, so maybe the experiment failed.”

Telus told TBIJ it recruits its moderators carefully and “delivers robust training (ongoing), and provides a best-in-class, holistic wellness framework.”

Grindr has also increasingly downsized its internal trust and safety team, and now relies more heavily on outsourced workers. Bumble, meanwhile, has gradually reduced its network of freelancers and hired a team of content moderators based in India through outsourcing firm TaskUs, which is headquartered in Texas but recruits the bulk of its staff from the Philippines. Staff members also said that internal roles were not immediately backfilled, leaving the member safety team under capacity.

Three former TaskUs workers on its Tinder and Bumble moderation accounts reported their working conditions were broadly good and that they could access mental health benefits, though one said his monthly salary of 18,000 rupees (£180) was “way too low”, and that he’d got into debt to cover his living expenses and tuition fees.

TaskUs told TBIJ: “We have built an industry leading content moderation practice where our number one priority is the health and safety of our teammates.”

While Bumble and Grindr have tens of millions of active users all over the world, their workers generally reported that global language support was poor. Most told TBIJ that moderators were required to review content or respond to users in languages they did not speak using a translation tool.

Irma, a former Grindr worker who left in 2019, said translation tools she had used at PartnerHero were sufficient “basic stuff, like troubleshooting” but not for detailed abuse reports. “It was very hard because everything got lost in translation,” she said. “There was no connection between the user and the person trying to help them.”

Kristen also expressed concern about Bumble losing a diverse workforce with many different language abilities. “I think there’s been a shift in quality through not having native speakers,” she said. “Putting everything through a translating service, you’re just never gonna get the best results or be able to provide the best service.”

Bumble told TBIJ: “Freelancers are retained in markets with nuanced language and cultural sensitivities to ensure we have global coverage.”

Uncertain future

Layoffs have been a central feature of the US tech industry in the last two years as interest rates have risen and venture capital funding has dried up.

“When companies are trying to increase their [profits] they look at operational costs,” said Sarah, a worker who left Grindr this year. “Usually [for] customer operations and content moderation, there’s a really big dollar amount attached to that. So that’s usually the first thing that’s on the table to be cut.”

Sarah said projects aimed at preventing banned users from getting back on Grindr and reducing moderators’ exposure to distressing content such as child abuse material had been deprioritised in favour of cost-cutting and increasing revenue.

Grindr told TBIJ it “will continue to invest heavily” in automation processes that protect moderators from distressing content.

Match Group has also deprioritised safety measures since 2022, according to three people who formerly held senior roles at the company. These cuts had left trust and safety teams overstretched, two of these people said.

Match Group told TBIJ: “We have increased our safety investments and brought in leading safety executives who have continued to build new roles and expanded existing safety functions, resulting in a 30% growth of our trust and safety teams over the past year.” (It did not specify whether these teams included outsourced workers.)

And at Grindr, an already small internal safety team has been slimmed down further by mass resignations after the company’s enforcement of a strict return-to-office policy.

In August, Grindr management gave workers two weeks to decide whether they would work twice a week from offices in Chicago, Los Angeles or San Francisco. Almost half of its 178 employees declined and were forced to resign, according to the Communications Workers of America (CWA), which is representing the workers. Grindr said in a statement to Insider that the CWA’s claims were “without merit”.

The CWA alleges the enforcement of the return-to-office policy was in retaliation to the formation of the Grindr United union in July, and has filed a case for unfair labour practices.

Erick Cortez, a former employee who was involved in the union drive, said Grindr United was formed “to protect what we loved about working at Grindr while also addressing serious concerns such as the mental health and safety of direct employees and contractors”.

“We believe that a union presence in decision-making is necessary to champion practices that prioritise worker and user safety at Grindr.”

Madison, a worker who stayed through the mass-resignations, said: “There’s just so many people who are gone. Like, there's barely anyone, there's no manpower to really fix things.”

“[Grindr]’s no longer a safe app,” said Joseph, another staff safety worker who has recently left the company. “It wasn’t a safe app to begin with. We were begging for help, and just never received it.”

Grindr told TBIJ: “Our safety and legal teams, which are sufficiently resourced, continue to review complex user reports as necessary.”

According to two sources, there are just three internal safety staff left at Grindr. They oversee teams at PartnerHero, which are now covering the entirety of its moderation work – including complicated legal requests and the crisis management team.

“It’s just a great degree of uncertainty and fear,” Madison said. “It’s hard to continue to serve the greater community … in the face of being treated like shit.”

Some of her former Grindr colleagues – and their counterparts at other apps – expressed their relief at having left the industry.

Ana says her health has improved. “Today, I can go outside and do some errands on my own,” she said. “My family is still worried … but I’m in the process of regaining my independence.”

Gael too says he now feels “a lot lighter.” “I was very happy when I left the job [at Bumble]. Because although it paid really, really well … it was affecting my life a lot.”

But others have taken their place. A former senior manager at PartnerHero said the industry sees outsourced workers as disposable: “When they burn out, they just bring the next one. And there’s plenty of people who are willing to get in the door.”

All the names of the moderators the Bureau spoke with have been changed.

* The fourth paragraph of this article was amended on Monday 20 November to clarify that Ana worked for Grindr via an outsourcing company

- Samaritans can be contacted 24 hours a day, 365 days a year on freephone 116 123 or by email at [email protected]

Reporter: Niamh McIntyre

Tech editor: Jasper Jackson

Deputy editor: Chrissie Giles

Editor: Franz Wild

Production editor: Alex Hess

Fact checker: Chrissie Giles

Illustrations: Anson Chan

Our reporting on Big Tech is funded by Open Society Foundations. None of our funders have any influence over our editorial decisions or output.

-

Area:

-

Subject: