Backroom deals, mystery companies and a ‘killer lake’: inside DRC’s gas and oil auction

Minister in the spotlight as lucrative sell-off is plagued with allegations of favouritism

The five-bedroom house in a well-to-do neighbourhood of Calgary, Canada, gives little away. There is certainly no evidence from its neatly painted exterior that this is the corporate headquarters of an energy company entrusted with extracting gas from a “killer lake” in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

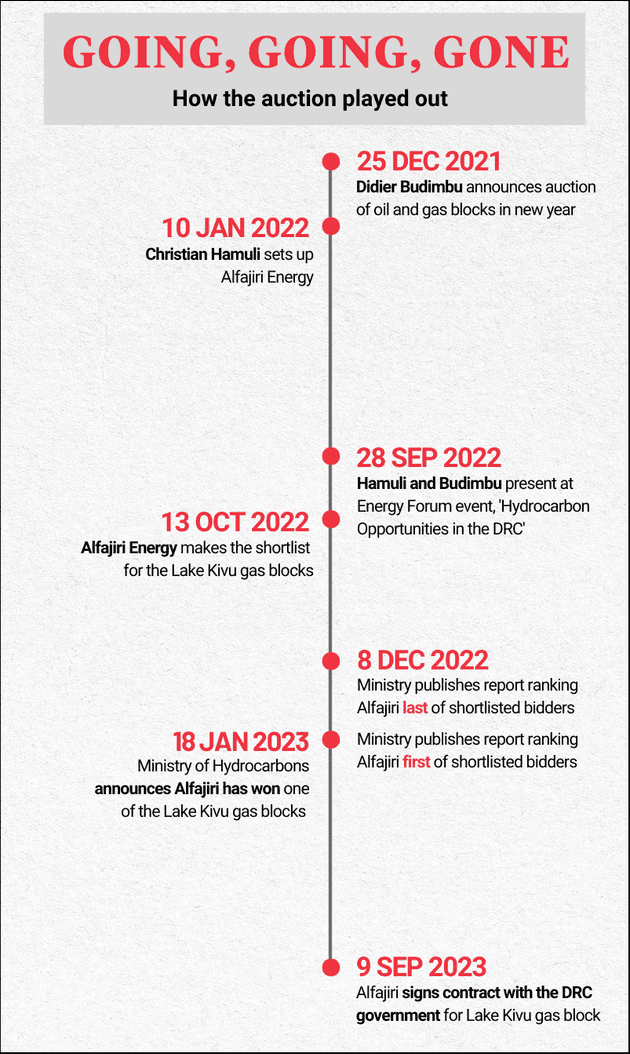

Alfajiri Energy was set up in January last year, just weeks after DRC announced its intention to auction off a raft of oil and gas blocks. One year on, the little-known company won the rights to a gas block in Lake Kivu, which holds vast amounts of gases that threaten to explode into the air if improperly managed.

Now, an investigation by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and Reuters can reveal that DRC’s oil and gas block auction has been plagued with apparent preferential treatment and backroom deals. And major questions have been raised about the company tasked with extracting gas from Lake Kivu’s depths.

In October last year, the Ministry of Hydrocarbons announced that Alfajiri had got past the first stage of the auction, despite its complete lack of credentials or expertise for the job at hand. Given that Alfajiri had been set up just 10 months previously, it could not have provided the three years of financial statements required by law for it to go through to the next stage.

In December 2022, experts from DRC’s Ministry of Hydrocarbons produced a damning report on Alfajiri, seen by TBIJ and Reuters. This detailed how its bid lacked vital information such as a work plan or feasibility study and that only three of its 20 supposed workers had actually committed to the project. Overall, Alfajiri scored lowest of the three companies bidding for the gas block.

Yet the same experts then produced a second report, which represented a remarkable U-turn from the first. Here, the writers had deleted key concerns and changed scores, which were tallied up – incorrectly – to reposition Alfajiri as the highest-scoring bidder. That result was confirmed a month later, when the ministry announced that the company had won the rights to extract gas from Lake Kivu.

The residential Calgary address where Alfajiri Energy is registered

The residential Calgary address where Alfajiri Energy is registered

At the centre of this process was DRC’s minister of hydrocarbons, Didier Budimbu, a man who has been in prison for fraud in Belgium. Two sources with first-hand knowledge of the auction told TBIJ that Budimbu pressured ministry experts to change the report, effectively rigging the auction in Alfajiri’s favour. A third source also said the process had been interfered with. A fourth source said Alfajiri had not met the requirements to win the block.

Just a fortnight before Alfajiri was announced as a qualifying bidder, the minister had travelled to Calgary where he and Christian Hamuli, Alfajiri’s president and chief executive, spoke at a lunch promoting hydrocarbon opportunities in DRC. This alone raised questions, according to a source familiar with the auction, who said it was improper for Budimbu to meet with just one of the bidding companies at that stage in the process.

Further inquiries about Alfajiri and its chief executive have cast more doubt on the company’s credentials. A source involved in the bidding process said a team sent to Canada by the DRC Ministry of Hydrocarbons to assess Alfajiri’s suitability found the company had no financial statements or official business space. Official documents show the company is registered at Hamuli’s Calgary home. “The man said he worked at home,” said the source. “He didn't bring [the team] to his banker, he didn't bring them to his partners.”

Though Alfajiri has been deemed fit to preside over the gas block, it may well not be the final operator, according to Vincent Rouget, a director at the consultancy Control Risks. “The real value for the owners of these companies wouldn’t lie so much in these blocks but in managing to sell them onwards to a bigger operator in the future,” he said.

Budimbu himself is no stranger to controversy. Five years before his first ministerial appointment in 2019, he was behind bars in Belgium. Newly uncovered court filings show he was sentenced to two and a half years in prison for fraud and money laundering having been part of a group charged with defrauding a married couple of €2 million by blackmailing them with nude photos. Money was sent onwards to bank accounts in Africa, with proceeds also spent on luxury goods.

Hear about our latest investigations, before they break

Budimbu disputed the idea that any company should be rejected from the first phase of bidding because it failed to meet one of the requirements. He also told TBIJ that the expert committee that produced the reports on companies in the oil and gas auctions had to defend them to another, higher body. This, he said, could result in changes. However, he did not explain why the ministry experts themselves changed the report. Any claims he intervened were based on partial information and could be politically motivated, he said.

Budimbu added that he maintains transparent relations with all potential investors in the tendering process, reassuring them that “the Democratic Republic of Congo is now the destination for those who want to seize the opportunity to do business”.

Hamuli said the process leading to the contract signature was “rigorous, transparent and credible” and rejected any notion that his company benefited from inappropriate meddling. “I can stand and testify that it was on merit. I didn't have to bribe the minister, the poor guy.” He added that Alfajiri was a start-up with a vision to help in the fight against energy poverty in DRC. He said the company had “highly qualified and experienced professionals with integrity” who were capable of developing the Lake Kivu gas extraction project in a secure manner.

A high-risk auction

The Alfajiri bid is not the only aspect of DRC’s oil and gas auction to have raised eyebrows. In July, Budimbu was photographed receiving four Toyota Land Cruisers that had been gifted to the ministry by French-British oil company Perenco – which was waiting to hear whether it had won the right to extract oil in two new blocks in the country’s coastal region.

The government has since announced that Perenco got through to the next stage of the auction for both blocks. Perenco said the donation – described by Greenpeace as a “curious gift” – had been agreed before the auction was launched and was in aid of the fight against oil smuggling.

Further revelations suggest there were irregularities before the oil and gas bidding process was even launched. In September 2021, Budimbu signed a three-way agreement to assess DRC’s oil reserves. The companies involved were GeoSigmoid, an oil and gas consultancy, and Clayhall Group, which was registered in Dubai by Ayo Ojuroye, a Nigerian betting tycoon.

A terse letter from Ojuroye to Budimbu one year later appears to shed light on Clayhall’s role. Ojuroye wrote of the urgent need to grant Clayhall the rights to the two oil blocks of his choice “as agreed in the contract”. He noted that his company had taken on the risks associated with financing the study of DRC’s oil reserves.

Those risks were high: two sources said the contract was worth $5 million. Yet one scientist who worked on the studies said they were hired to interpret existing data – office research for which a $5 million fee would be astronomical, according to a consulting geologist unconnected with the auction.

Budimbu mentioned the contract with GeoSigmoid in a cabinet meeting in May last year, asking for funds to pay for the studies. In fact, Clayhall had already agreed to pay for the studies in exchange for a restricted auction that would grant it rights to exploit two oil blocks – all of which went unmentioned by Budimbu. Congolese law states that a restricted auction can only be authorised by the cabinet. Two sources said the contract was kept hidden.

In an air-conditioned office crowded with aides and advisors in DRC’s capital, Kinshasa, Budimbu told TBIJ that the law allowed him to organise a restricted auction in exchange for funding but denied there was any such agreement in this case.

Neither Clayhall nor GeoSigmoid responded to TBIJ’s requests for comment.

Lake Kivu, straddling the border of DRC and Rwanda, where little-known company Alfajiri has won the rights to drill for gas

Eye Ubiquitous/Alamy Stock

Lake Kivu, straddling the border of DRC and Rwanda, where little-known company Alfajiri has won the rights to drill for gas

Eye Ubiquitous/Alamy Stock

A shortage of bidders

Since the auction for the oil and gas blocks was launched last year, the government has struggled to attract bidders and a number of major companies, such as TotalEnergies, have said they will not take part.

The government has promised that the auction will bolster the economy in one of the world’s poorest countries but DRC’s legacy of corruption and political instability means it is seen as a high-risk place to invest. “Any additional allegations of corruption, preferential treatment [or] favouritism will just go further in deterring large-scale reputable investment in the sector,” said Rouget of Control Risks.

Questions have been raised about whether some of the projects are viable at all. A number of the blocks being auctioned off are in central regions of the country that can take days to reach; exporting oil from these areas would involve building hundreds of miles of pipeline through dense rainforest. Similar licences acquired from the government in the past have remained unused for years due to the huge investment they require.

One person with knowledge of the auction suggested there had been no bidders for the blocks in the rainforest this time around; the deadline for bids on those has been pushed back to next year.

Rouget said the government may have hoped the licensing round would raise funds ahead of the upcoming election, slated for December. On signing a contract with the government, successful bidders pay hefty upfront fees. These are subject to negotiation but range from $200,000, for remote blocks with little information on them, to $5m for those with confirmed fossil fuel reserves.

In the case of Alfajiri, there appeared to be a sizeable gulf between the expectations of each party: the government asked for $3.9 million while the company’s counter-offer was just $20,000.

The auction, however, continues to progress. Last month Hamuli travelled from his home in the Calgary suburbs to Kinshasa to sign a contract with the DRC government, promising that people from both Congo and Canada will work on the project side by side.

Header picture: Didier Budimbu.

Reporters: Josephine Moulds and Hajar Meddah

Additional reporting: Simon Lock and Meriem Madhi

Environment editor: Robert Soutar

Impact producer: Grace Murray

Deputy editor: Chrissie Giles

Editor: Franz Wild

Production editor: Alex Hess

Fact checker: Edward Siddons

This reporting is funded by the Sunrise Project. None of our funders have any influence over our editorial decisions or output. This story was produced with the support of the Pulitzer Center's Rainforest Investigations Network.

-

Subject:

-

Area: