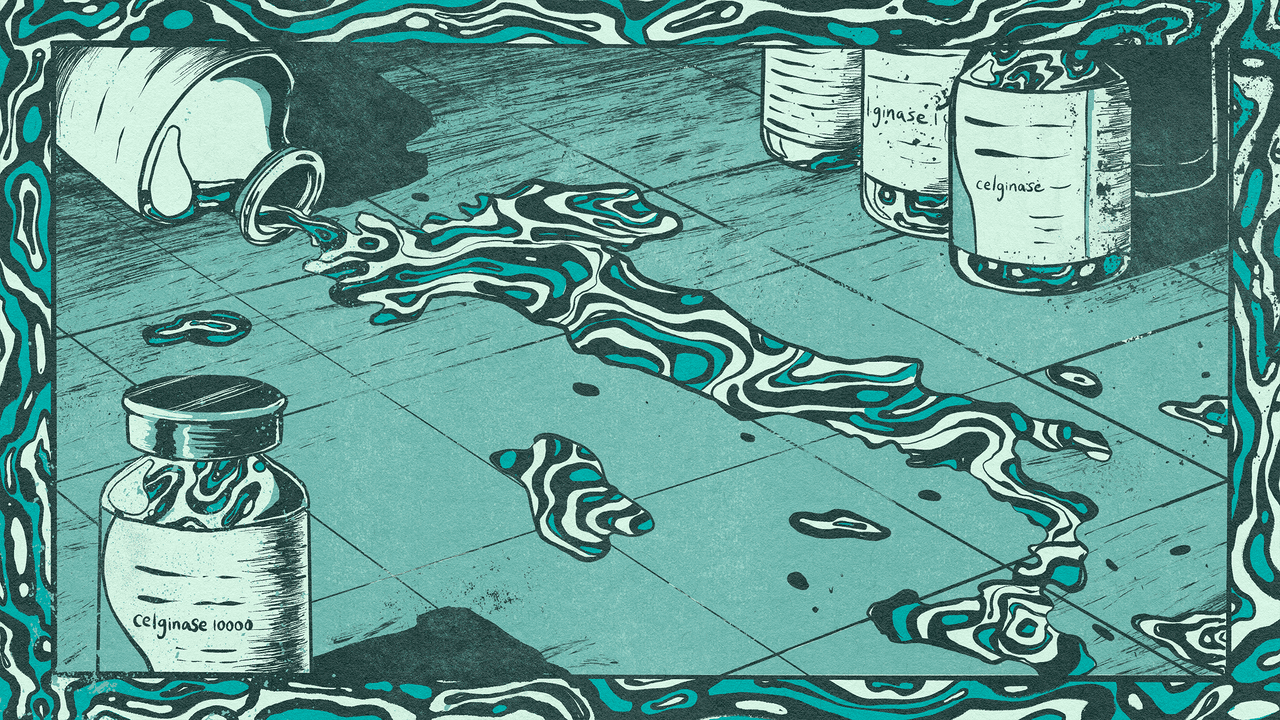

Italian hospitals imported unapproved, substandard cancer drug

At least 16 hospitals in Italy have been treating cancer patients with a poor-quality imported drug that is not approved for use in the EU, the Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ) and POLITICO can reveal.

Gaps in national and EU regulation have allowed Italian hospitals to legally request shipments of Celginase, a low-cost cancer medicine shown to be substandard, even when better alternatives have been available.

Neither Italy’s drugs regulator nor the country’s ministry of health are responsible for checking the quality, efficacy or safety of this drug before allowing it into Italian hospitals. Nor does this fall within the remit of the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

Hundreds of vials of the drug have arrived from India over the last seven years. It is unknown how many cancer patients could have experienced adverse side effects or lower chances of remission as a result. Many vials still sit on hospital shelves today.

Celginase is a brand of asparaginase, a drug used to treat acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, the most common form of childhood cancer. Celginase is made and approved in India, and costs a tiny fraction of the price of the “gold-standard” brand: as little as €13 a vial compared with about €2,500. Published academic studies have found it did not meet minimum manufacturing standards or consistently reach the clinical activity threshold to treat cancer.

In January, TBIJ and STAT revealed that poor-quality brands of asparaginase, including Celginase, have been shipped to more than 90 countries since 2016, putting an estimated 70,000 children around the world at risk.

In 2018, an apparent nationwide shortage of Oncaspar, the “gold-standard” asparaginase, led to children in Italy receiving another brand, Aspatero, which was later found to be substandard. (The hospital concerned said its request to import Aspatero was authorised by the Italian drugs regulator, and that not doing this would have “reduced the chances of children’s recovery.” The drugs regulator confirmed it had authorised the import.)

But TBIJ and POLITICO can now reveal that Celginase has been purchased by Italian hospitals even when the gold-standard product has been available – in some cases as recently as this year. Further records show that Celginase was also imported by seven Italian regional health departments, suggesting that the actual number of hospitals using the drug could be far higher.

Informed consent paperwork does not detail the brand of the drug that patients will be given nor the countries in which it is approved. Patients are being left in the dark.

Lack of liability

There are several different types of asparaginase. “Native” asparaginase is made from Escherichia coli (E. coli). Turning this bacterium into medicine is complicated and even good-quality native asparaginase can cause side effects, including severe allergic reactions.

For this reason, doctors prefer to use modified versions of asparaginase. These are less likely to cause allergic reactions but are much more expensive up front.

Although Celginase and Oncaspar are both asparaginases, they are different: Celginase is native, Oncaspar is modified. Oncaspar has been approved for use in Europe since 2016 and is the brand of asparaginase recommended as first-choice treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.

In Italy, if a drug is in shortage, doctors and pharmacists can ask the Italian drugs regulator to greenlight the import of that same drug from another country.

A different law permits a drug that is not approved in the EU but is elsewhere in the world – such as Celginase – to be imported for an individual named patient if a doctor deems there is “no valid alternative therapy available”. As Celginase and Oncaspar are not exact equivalents, doctors have been able to request Celginase imports even if Oncaspar is available.

Crucially, this process bypasses the country’s drugs regulator. In Italy, permission is instead given by the ministry of health’s customs agency, which is required only to check that the paperwork has been correctly filled out by the hospital and the drug arriving is the one requested.

It is not required by law to check the quality of imported drugs nor ask for data from the overseas regulators that approved them.

Instead, the responsibility for these drugs lies with the individual doctor who requests them. The Italian drugs regulatory agency said that doctors should use qualified and reliable import intermediaries who can guarantee the quality and safety of the drug, particularly with suppliers in non-EU countries, and that doctors should get informed consent by giving the patient complete, transparent and exhaustive information on the drug.

Through freedom of information requests to the Italian customs agency of the ministry of health, TBIJ and POLITICO found that at least 16 hospitals, including the Istituto Nazionale Tumori in Milan and San Camillo Forlanini in Rome, imported hundreds of vials of Celginase into the country over a seven-year period. (The Istituto Nazionale Tumori said that shortages required them to source Celginase. It added that the patients who received the drug are either responding to it or are in remission, and that the Italian drugs regulator has never provided information showing that Celginase could be harmful. San Camillo Forlanini did not respond to a request for comment.)

Attilio Guarini, a doctor who treats patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia at Policlinico di Bari hospital, says there is no clinical guidance recommending doctors turn to a native asparaginase – such as Celginase – if Oncaspar is available.

The Italian drugs regulator told TBIJ that it denies any responsibility for the “efficacy and safety” of medicines imported from non-EU countries that are not authorised in accordance with EU regulations.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) also has no power over imports of unapproved drugs from non-EU countries, according to its former head Guido Rasi.

Most of the Celginase imported into Italy from India came via Switzerland. The Swiss customs agency said it does not have specific data on the products we asked about. It did not know if Indian asparaginase imported via Switzerland may have gone to any other EU countries besides Italy, but it is understood that Celginase was not used in Swiss hospitals.

The EU issue

In certain situations, such as drug shortages, it is vital for European countries to be able to import medicines that may not be approved in the EU.

In 2001, the EU published new bloc-wide legislation allowing medicines that “fulfil special needs” to be excluded from the standard European rules around quality, safety, efficacy and manufacturing. But only under strict conditions.

Any such medicines (which may include those not approved in the EU) need to be formulated according to the specifications of an authorised healthcare professional – such as a doctor or a pharmacist – and given to an individual patient under this worker’s “direct personal responsibility”.

Each country has incorporated this into its own national law in different ways.

In Italy, the prescribing doctor must justify the exceptional use, which is then checked by the customs agency of the ministry of health. In Spain, the hospital or health department must request access to the unlicensed drug from the regulator. In Ireland, the doctor issues the prescription and the wholesaler or manufacturer is required to notify the regulator of the import.

And while the EU law was meant to be applied to individual patients, in practice this is not always the case. In Germany and Italy, for instance, there are provisions for orders large enough to temporarily stock a hospital pharmacy. In Ireland, the law has been used so extensively that in 2020 more than 1.5 million packs of the 50 most popular drugs were brought into the country under the rules.

“If products for commercial sale are routinely entering the EU as unlicensed medicines and they've been supplied under the named-patient […] regime then that’s an issue,” says Grant Castle, partner at Covington law firm.

He said these rules allow patients to access medicines where there is a bona fide medical need and are “not a suitable basis” to import medicines for other reasons. “If that is happening, it’s a loophole.”

While it is down to member states to put rules in place for named-patient supplies of unlicensed medicines, Castle added, national rules “generally do not provide the same safeguards”.

Gilles Vassal, a paediatric oncologist and board member of the European Society for Paediatric Oncology, agreed. When addressing shortages by importing medicines unauthorised in the EU, he asks: “What are the measures set up at [the national] level to control the quality of the medicine they are importing?”

The Italian drugs regulator said that in February 2023, it exchanged information with WHO on data around a potential lack of efficacy of the Indian-sourced drug Aspatero provided by the study highlighted in TBIJ’s first story. It added that there appears to be no evidence from the WHO or national regulatory authorities of low-quality, dangerous or ineffective asparaginases imported from India.

However, a European Commission spokesperson said that the Italian drugs regulator and other Italian authorities have been investigating this issue, which involves some specific Italian hospitals. A WHO spokesperson said it had contacted the countries reported in TBIJ’s original investigation into asparaginase, but that no “actionable information” had been received.

Changes to the EU law are also in the works to attempt to address some of these concerns. A planned revision of the bloc’s pharmaceutical legislation would include a line stipulating that countries “shall encourage” doctors and patients to report data on the safety of the use of unlicensed medicines to their own regulator.

It would also oblige drugmakers to flag any potential shortages six months in advance – up from two months – and it could require companies or wholesalers to keep larger stockpiles.

In Italy, the customs agency has responded to TBIJ’s enquiries by working to modify its forms so doctors must give more detail about clinical reasons for the import. “We realised that there are loopholes in the system, so we are now working to fix them,” said Ulrico Angeloni, one of the agency’s coordinators.

Doctors that TBIJ and POLITICO spoke to would like to see national measures to verify the quality of unlicensed drugs accessed via these loopholes, as well as more transparency on their use, effectiveness and safety.

For now, the paradox remains that while Europe’s medicines are among the most highly regulated in the world, drugs that are shipped in from abroad can fail to meet even minimum standards.

The manufacturer of Celginase did not respond to a request for comment.

This article was updated on 30 June and 3 July 2023 to reflect comments received after publication.

Reporters: Laura Margottini and Rosa Furneaux

Additional reporting: Maria Cristina Fraddosio

Illustration: Evangeline Gallagher

Deputy editor: Chrissie Giles

Editor: Meirion Jones

Production editor: Alex Hess

Fact checkers: Alice Milliken and Meriem Mahdhi

This article is part of our Global Health project, which has a number of funders including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.

-

Area:

-

Subject: