The Del Monte deaths: shocking claims of violence at pineapple plantation

Content warning: This story contains descriptions of graphic violence.

Stephen Thuo Nyoike’s battered body was found by the side of the road. He was 22. “He had been strangled with a wire,” says an eyewitness. “And there was a pineapple near the body.”

The last time anyone saw Stephen alive, they said he was being beaten with wooden clubs by security guards working for the food giant Del Monte. A post mortem showed his cause of death as strangulation and blunt-force trauma to the head. Further injuries to the wrists indicated his hands had been tied.

“Stephen was a good kid,” says his father, Joel. His son had been taking welding lessons for over a year and planned to set up his own workshop. But on the night of 30 August last year, he was killed violently after taking part in a botched pineapple raid on Del Monte’s megafarm outside of Thika, central Kenya. These attempts to steal fruit – often involving young men storming the premises on motorbikes – have become a semi-regular occurrence at the plantation, both a symptom and a cause of escalating tensions between local villagers living in poverty and the company whose sprawling farm dominates the area.

Stephen’s body was next to a road just outside of the farm when Joel arrived on the scene the next morning. “He was lying face-down,” he says. “I turned him over and he had injuries on his forehead. And his throat looked like it had been strangled with wire.”

Two men who were with Stephen on the raid said the group had been ambushed inside the farm by guards. “I looked back and saw the guards with torches,” remembers one. “I heard a harsh voice shouting: ‘Catch! Catch! Kill!’”

He remembers escaping and hiding in a bush, where he watched as the guards beat Stephen. He says the beating went on for about half an hour, until Stephen went quiet, and his motionless body was loaded onto a Del Monte pickup truck.

As Joel and other witnesses gathered around the body the next day, they noticed a large group of Del Monte guards watching them from across the road.

The second man remembers the shock he felt when he saw the body. “I have seen others who have been killed inside the farm,” he says, “but ‘Thuo’ was extreme. The wire…”

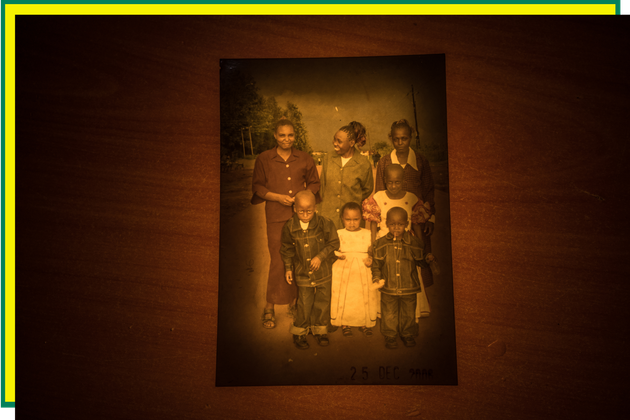

Stephen Thuo Nyoike (bottom left) with his family as a child

Stephen Thuo Nyoike (bottom left) with his family as a child

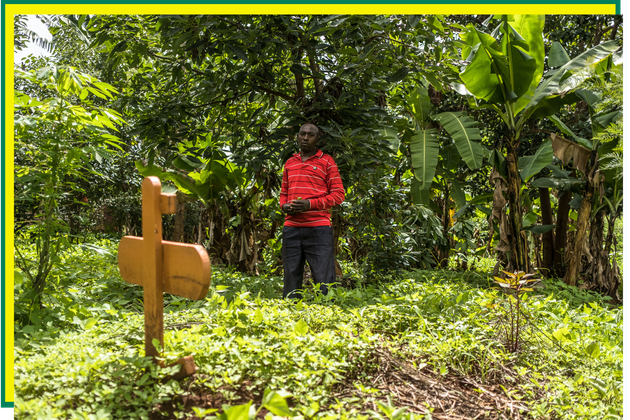

Joel stands over the grave of his son, Stephen

Joel stands over the grave of his son, Stephen

A global enterprise

Stephen is one of six people allegedly killed by Del Monte security guards in the last decade, with all the deaths centring around the same vast pineapple farm. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism and the Guardian have uncovered numerous allegations of violence perpetrated by guards on the farm, which supplies Del Monte’s pineapples to British supermarkets including Tesco, Asda and Sainsbury’s.

The shocking scale of the accusations has been captured by the law firm Leigh Day in a letter to Del Monte detailing 146 alleged incidents involving 134 locals over a decade. It includes claims of five deaths – all since 2019 – as well as reports of dozens of serious injuries and beatings that have left people unconscious. It also includes five allegations of rape.

Del Monte said that it took the allegations “extremely seriously” and that it has “instituted a full and urgent investigation” into them. It said that the conduct alleged is in “clear violation” of its “longstanding commitment to human rights” and the policies and procedures it has in place.

Tesco said it had suspended orders on all products sourced from the farm until an investigation is concluded. Waitrose said it expects its suppliers to comply with “strict ethical standards” and that it welcomed Del Monte’s review.

The British Retail Consortium, the industry body that represents UK supermarkets, said it welcomed Del Monte’s investigation and its “commitment to constant improvement in working practices”.

Del Monte’s 80 sq km plantation sits on the border of Murang’a and Kiambu counties, about 40 kilometres northeast of Nairobi, in a landscape marked with lush green vegetation and rich red soil. The area is also blighted by poverty, unemployment and drug use. This deprivation is despite the money generated by Del Monte, whose pineapple exports earned the country’s economy more than $100m in foreign exchange in 2018. This financial firepower has provided the company with political clout.

Among local villagers, the vast farm is often described as kwa guuka, meaning “our grandfather’s”. It is a bitter reference to the fact that many families were forcefully evicted from the land when it was first acquired by the company’s predecessor several decades ago.

The farm is the single largest exporter of Kenyan produce to the world. This huge global operation means that, although countless pineapples are grown in the area every year, virtually the only ones sold locally are those that have been stolen from the farm.

“The boys around don't have anything much to do, and they need money for their survival. So the easiest way is to go and raid the farm, get the pineapples and sell to the public,” says Joel. “Mostly it's driven by peer pressure and poverty.”

These conditions stand in stark contrast with the lifestyle enjoyed by the 237 guards employed by Del Monte at the farm, who have fully serviced schools, hospitals and sports grounds on company premises.

Their job is to patrol the huge farm with the aid of watchtowers, drone surveillance and guard dogs. The guards have been subject to violence themselves – thieves have been known to throw stones to ward them off, with one guard losing an eye in a recent raid – but this pales in comparison to the litany of allegations against them.

They work round-the-clock shifts in green Toyota Land Cruisers, occasionally accompanied by local police. Ngati police station is even located on the farm, close to Del Monte staff quarters.

Del Monte is the biggest private-sector employer in Kenya and the farm provides thousands of locals with work. But it hires many of its labourers on a casual basis and, locals say, lets them go after a few months. In January of last year Del Monte workers went on strike. The company responded by labelling the action illegal.

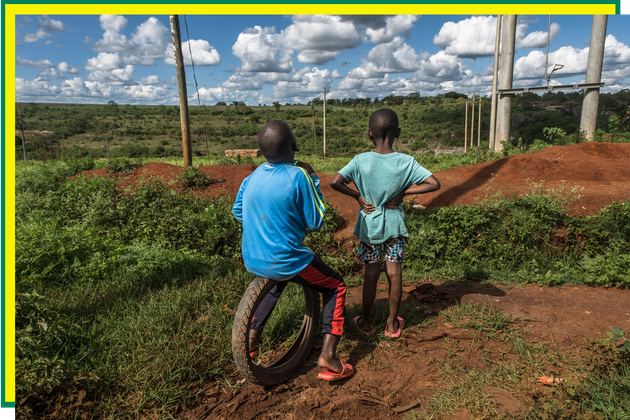

Locals refer to the sprawling farmland as 'our grandfather's'

Locals refer to the sprawling farmland as 'our grandfather's'

Stephen’s mother, Grace Mbinya, is now too traumatised to visit the garden where her son is buried, his grave surrounded by banana trees. In her grief she has wiped her phone clean of any pictures or links to him.

“He was a good boy, doing any house chores that I gave him,” she says tearfully. “The night before [he died], he had cooked part of the family dinner and we sat with him till late talking about a lot of things including his promise to buy me a piece of land where we would relocate.

“They should have just arrested and jailed him … where he is now, I can never see him and I will never see his children.”

Neither of the men who were with Stephen on the raid reported that night’s events to the police. “If you go to the police you will be arrested immediately so you don’t dare,” one says.

A senior police officer was unable to explain why, eight months later, there had been no investigation into Stephen’s death.

‘There’s no justice’

Dogged by poverty and brought up on the belief that Del Monte is too big to be tried in court, many families in the area have given up on pursuing justice for injuries and deaths. Even when action is taken, the justice system moves slowly.

Bernard Murigi Wanginye, a quarry worker, was 26 when he died after joining a pineapple raid in April 2019. When his father, Gilbert, went to the morgue to identify the body, he was so appalled by his son’s condition that he fainted.

“His head was badly damaged and I could not look for long,” says his mother, Alice. “I just walked out.”

“He used to support us very much,” says Gilbert. “Whenever I remember my son I really get down.”

Today, five former guards, who have since been fired by Del Monte, stand accused of Bernard’s murder. They pleaded not guilty in July 2019. The same month, a judge directed that the trial be “fast-tracked”. But four years later Gilbert is still waiting for the trial to take place.

On 27 April of this year, the guards appeared in court for another hearing. But a new hearing date was given for 5 September, delaying justice still further. Gilbert was not there. No one had told him about the hearing.

“There’s no justice at all for Bernard,” says Alice. “I’m urging the people out there to please assist us to get justice for our sons.”

It is understood that Del Monte says it has improved its security and safety practices since Bernard’s death in 2019. Planned or implemented improvements are said to include updated radio communications systems; training guards in new formal rules of engagement and enhanced formal processes around allegations of violence.

‘I tried to plead with them’

“I felt a lot of pain,” remembers Burnice Kagori Maina of the day she heard that her son had died. “And I feel that pain today.”

It has been 10 years since the body of Burnice’s son, Saidi, was retrieved from a dam on the farm. The discovery, in May 2013, added fuel to decades-long local rumours that the dams had been used to hide the bodies of other people reported missing in the area.

Two witnesses who were with Saidi Ngotho Ndungu the night he died went on to testify in a lengthy court process. Yet this turned out to be an inquest rather than a criminal case. Burnice had no idea what was happening, believing that her son’s case had frozen for no apparent reason.

One witness statement, provided to police two days after the body was found, states that Saidi was chased by Del Monte guards who caught him and started to beat him. The witness claims to have heard Saidi pleading with the guards not to kill him before hearing “something thrown into the nearby dam”. Though the death certificate says he drowned, one witness says there were visible injuries to his face when his body was removed from the dam.

As well as alleged violence against trespassers, the guards have also been accused of completely indiscriminate attacks. These include an incident on the evening of 25 September 2021, when a minibus carrying 14 people home from a party at night broke down on a public road within the farm. Then, witnesses said, the guards set upon the guests, leaving them with various injuries. “I tried to plead with them,” said one man who sustained a broken leg. “I told them we were not there to steal pineapples.”

The Kenya National Commission on Human Rights is also investigating an alleged attack last December by guards on two men as they slept by the side of the road next to the farm. One of the men was John Rui Karia, a 52-year-old former labourer at the farm who had turned to selling grass next to the road after he was let go.

“We ran to help but the guards were faster,” says Boniface Nduva, who was working on the side of the road shovelling sand.

“They started beating them and then the older man, Rui, started screaming,” says Dennis Mutiso, a grass seller who watched from the roadside. “When I heard that I ran away and then I heard them being loaded into the Del Monte car. They were being stamped on when they were inside the car.”

Guards on the farm are typically armed with wooden clubs

Guards on the farm are typically armed with wooden clubs

Del Monte's vast farming operation dominates a region blighted by poverty

Del Monte's vast farming operation dominates a region blighted by poverty

The beating allegedly continued in a nearby Del Monte security office before John was taken to Ngoliba police station, where he arrived in a critical condition. But instead of being taken to a hospital, he was taken to a rudimentary clinic on the plantation and given painkillers. The next morning he arrived in court for a plea hearing, charged with pineapple theft. He was driven there in a Del Monte security vehicle.

Two witnesses said John needed help getting out of the car. One said he started vomiting up blood outside the court. He was allegedly told by an accompanying officer that he would appear in court even if he died. John pleaded guilty.

After a week on remand in Thika prison, where he continued to be denied medical care, John was eventually taken to Thika hospital on 28 December. He was pronounced dead on arrival.

A pathologist’s report revealed the gruesome extent of his injuries, including “multiple contusions” of the abdomen, lungs and brain, and “defence injuries” to the forearms. His cause of death is listed as “injury due to multiple blunt force trauma to the head” as well as “abdominal and multiple soft tissue injuries”.

Witnesses say the attack that killed John was unprovoked. “They were not stealing,” says Nduva. “They had worked the whole day and were just there sleeping.”

‘Someone buying these pineapples should know’

“There has been real misery that is caused by this farm to local community members,” says Mary Kambo of the Kenya Human Rights Commission “There is a lot of power and leverage that can come from the markets and consumers. It’s important that someone who is buying these pineapples knows about the allegations of violence connected to the farm.”

A spokesperson for Del Monte said: “We take these allegations extremely seriously and have instituted a full and urgent investigation into them. The conduct alleged in these cases is in clear violation of Fresh Del Monte’s long-standing commitment to human rights and the comprehensive policies and procedures we have in place to ensure our operations respect the dignity of all individuals.

“Our proactive investigations continue and will be supported by an independent review by a specialist human rights consultancy. We continue to fully support the Kenyan authorities' investigations, including into the death of John Rui Karia. We are committed to constant improvements in the way we operate to adhere to the highest international human rights standards in all our businesses.”

For the families of the victims, justice continues to move slowly if at all. None of the six deaths linked to the farm are yet to result in a single conviction.

Kenya’s justice system has however shown itself to be capable of acting firmly on one issue: people caught stealing pineapples can receive lengthy prison sentences. In 2008, three men were brought to trial for the attempted armed theft of 30 pineapples, worth about $20, from Del Monte’s farm. They were found guilty of robbery with violence and sentenced to death.

Stephen’s father, Joel, says he has no hope that local police will help deliver justice to the the Del Monte guards who he believes killed his son.

“They don’t value life,” he says. “What they value most is pineapples.”

Header image: A photo of Bernard Murigi Wanginye (left) and his grave (right). Five former Del Monte guards currently stand trial for his murder.

Reporters: Edwin Okoth, Matthew Chapman and Emily Dugan

Project editors: Franz Wild, Chrissie Giles and Robert Soutar

Editor: Meirion Jones

Production Editors: Alex Hess and Frankie Goodway

Impact producer: Miriam Wells

Fact checker: Alice Milliken

Photography: Brian Otieno for the Guardian/TBIJ unless specified

Our Law for Change project is funded by David Graham and our Environment project is funded partly by Quadrature Climate Foundation and partly by the Hollick Family Foundation. None of our funders have any influence over our editorial decisions or output.

-

Area:

-

Subject: