The spies stalking British justice

From their mobile phones in their 12th-floor office in London, the team of corporate spies drawn from the UK military was able to keep constant watch on their quarry more than 40 miles away in rural Sussex.

They were monitoring the comings and goings at Hunters Farm, a 52-acre estate with an 18th-century country house belonging to the wealthy City of London solicitor Neil Gerrard.

A high-tech video camera camouflaged using techniques employed by the British army was hidden in a tree at the entrance to the estate. The faces of guests and their vehicle details were recorded and live footage was beamed back to London.

Gerrard was under 24-hour watch. He had incurred the wrath of a Russian-funded mining company, which had once been his client but now blamed him for a criminal investigation into its conduct.

The firm, Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation (ENRC), had hired a team of spies from Diligence International LLC, a private investigations company which employs former members of Britain’s intelligence service and special forces.

These intrusive surveillance tactics are increasingly part of multimillion-pound battles in the high court – often referred to as “lawfare” – in which warring wealthy litigants hire investigators.

These investigators are often former spies, servicemen or police officers trained at taxpayers’ expense in covert operations by the British state. After switching to the private sector, they cash in on these skills by using them to defend autocratic states, oligarchs and wealthy businesses.

Today an investigation by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and the Sunday Times can reveal how Britain’s unregulated private investigators spy on and follow opponents; attach covert trackers to cars; hold fake job interviews; steal private documents from bins; pose as the target’s family members; and pay witnesses who give evidence used in court. These tactics are laid bare in two cases which highlight the lengths former British armed forces personnel will go to help London lawyers win a case.

They raise concerns about the way Britain’s overstretched law enforcement agencies such as the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) can be outgunned by the power of a multibillion-pound business with bottomless pockets.

The art of lawfare

The rise of the corporate spying industry centres on the Royal Courts of Justice in London, which have become a global centre for quarrelling parties from around the world.

The UK corporate intelligence business is reported to be worth more than £15bn a year and rates charged to clients can be more than £800 an hour. Private investigators are unlicensed in the UK, unlike in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and most of the US.

The firms attract wealthy overseas businesses and nation states who can pay for all the weapons of modern lawfare: the best law firms and barristers, top public relations companies and increasingly corporate intelligence companies.

There is a win-at-any-cost mentality in which the corporate spies are paid to use advanced technology to gather information which might give their client the edge.

As a result, the British courts have accepted evidence which has often been dubiously acquired – such as hacked emails, documents obtained by deceit, and statements from witnesses who were paid.

Special forces operatives ‘blinded by the money’

One of the firms that has thrived in this era of London lawfare is Diligence. The firm is made up of highly trained ex-employees from the UK’s intelligence services and armed forces.

It was founded more than 20 years ago by Nick Day, a former MI5 officer. One of the Diligence group’s board members in those early days was William Webster, a former US judge who had the unique distinction of also being a former director of both the FBI and the CIA. The firm is currently run by Trefor Williams, a 51-year-old who is reported to be a former member of the Special Boat Service (SBS).

In 2010, the Diligence group was hired to work for Qatar to spy on Fifa officials and a rival bid team ahead of the vote for the hosting of the 2022 World Cup.

In the past, Williams has described how Diligence recruits many of its operatives from the Royal Marine Commandos or the Parachute Regiment – which are known to provide many of the soldiers for Britain’s special forces units, the SBS and SAS.

In interviews several years ago, Williams claimed that these elite soldiers were turning to the private sector because the pay in the armed forces was “crap”. He said: “They decide to leave because they’re blinded by the money and see the short-term gain." He added: In the military you spend most of your time doing courses. Now they get to do it for real.”

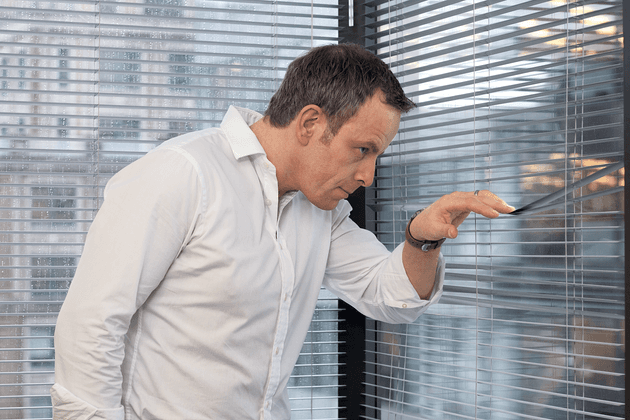

Trefor Williams, the head of Diligence, in the firm’s London office

Thomas Humery / Vanity Fair France

Trefor Williams, the head of Diligence, in the firm’s London office

Thomas Humery / Vanity Fair France

A source close to Diligence said: “In the UK security services they can do what they want because it is in the national interest. But it is a different story when you are acting in the interests of paying clients. They don’t seem to have a sense of when it is appropriate to use such tactics as subterfuge and surveillance. It is routine for them.”

A former Diligence investigator admitted: “I was never involved in a discussion about whether something was appropriate, proportionate or whatever else. It’s just, ‘Technically, is it possible? Physically, can we do it?’”

Lawyer ‘leaked documents for his own gain’

A former Metropolitan Police officer turned lawyer, Gerrard had bought his Sussex estate with money amassed during a career defending corporate giants and the ultra-wealthy.

In 2011, he was employed by Dechert, one of the world’s largest law firms. He had been tasked by ENRC to carry out an internal investigation into allegations of bribery and corruption.

Though it had headquarters in London, ENRC was owned by the Kazakh government and the families of three billionaire oligarchs who made fortunes from a series of privatisations in the former Soviet Union. The company maintained close ties to Russia.

In 2013, ENRC became the subject of a major investigation by the SFO. The inquiry centred on allegations that the firm had gained control of mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo by paying huge bribes to senior government officials. ENRC denies wrongdoing.

At some point though, bosses at ENRC began to suspect Gerrard was leaking sensitive documents to the SFO and the media. ENRC believed he was purposefully undermining the company in a deliberate attempt to create more lucrative work for himself. If true, it was a serious charge.

Investigators later hired by Harvey Weinstein

To begin with, ENRC hired Israeli corporate intelligence company Black Cube to investigate Gerrard. The firm has offices in Tel Aviv and London, and was set up in 2010 by Israeli intelligence officers.

Black Cube was later employed by lawyers acting for the film producer Harvey Weinstein to gather compromising information on several women who had accused him of sexual abuse and rape.

Adrian Leppard, the former commissioner of the City of London police, and Robert Amaee, ex-head of anti-corruption at the SFO, have seats on Black Cube’s advisory board.

One of the tactics used by Black Cube to find out more about Gerrard was the fake interview. In December 2013, a number of Gerrard’s colleagues at the law firm Dechert were lured to interviews at offices near the Barbican, central London, according to documents filed by Gerrard in court.

They were being offered an exciting work opportunity, but it did not exist. During a second round of interviews it began to dawn on the lawyers that the process was a sham. The questions were far too detailed on topics such as: their colleague Gerrard; the Dechert partners; and the firm’s relationship with the SFO.

In legal filings, ENRC said it was “legitimate” to hire Black Cube to investigate Gerrard’s “unlawful conduct”. The firm declined to address the allegations about the interviews in the legal case and a judge said they were undisputed.

In 2014, a mechanic discovered a tracking device attached to Gerrard’s car. The lawyer reported the intrusion to the police but no action was taken. It was never established who placed the device on the vehicle. ENRC denied involvement.

£400m legal fund to hire a dozen law firms

ENRC mounted one of the most sophisticated and expensive legal operations London had ever seen. It embarked on a huge legal offensive that would undermine Gerrard and counter the SFO investigation because it was convinced that both had acted unlawfully. The twin projects were given the codenames “Project Exodus” and “Project Genesis”.

ENRC’s parent company would go on to spend £400m on “professional fees and other exceptional litigation costs”, including hiring private investigators and more than a dozen law firms to work on the case. Lord Goldsmith, the former attorney general, was among those enlisted for legal advice.

The centrepiece of this offensive was a pre-emptive £70m legal action against the SFO in which it accused the agency of mishandling its investigation. In recent years, the SFO has suffered expensive failures in other cases against Barclays, Tesco and British American Tobacco.

In order to win its case, ENRC focused its attention on Gerrard to show that he had behaved improperly by tipping off the SFO when he was supposed to be representing the firm. It suspected that he had deliberately sparked the corruption investigation in order to create more work for himself.

So, in February 2017, the firm’s lawyers hired Diligence to spy on him.

A luxury mission

As the world of corporate spying has become more professional, the tactics have become more intrusive. Diligence began an intensive two-year surveillance operation against Gerrard.

The corporate spies would wait outside his office and follow him to meetings across London and abroad. They carried their passports in case he hopped on a plane, one source explained.

In January 2019, Diligence trailed Gerrard and his wife Ann, a magistrate, on a holiday to Mustique, the exclusive private Caribbean island.

According to court documents, Diligence’s operatives were Grant Yates and Sion Bailey, both former Royal Marines in their 40s. Yates, who was a lance corporal in the 40 Commando regiment, had served the British armed forces in both Kosovo and Iraq.

The pair managed to get seats behind the Gerrards for the nine-hour flight to St Lucia. However, they came unstuck when they attempted to make the 70-mile crossing from St Lucia to Mustique. The island only admits guests with pre-arranged accommodation, but Yates and Bailey had not booked anywhere. So they pretended they were the Gerrards’ nephews giving them “a big surprise”. The authorities made a quick call and the story quickly unravelled.

Undeterred, Diligence booked another spy, understood to be an ex-MI5 officer, into the island’s luxury £600-a-night Cotton House hotel a few days later. He fared no better: the St Lucia authorities were now on the alert and the last-minute booking by a lone male caught their eye.

When stopped at St Lucia airport, the operative claimed to be on a holiday paid for by his wealthy employer. Officials rifled through his luggage and discovered a large quantity of surveillance equipment, including a night-vision camera. He too was barred.

The Gerrards were alarmed at the attempts to pursue them. Their safety concerns were such that Sussex police officers met Ann at Gatwick when she returned on her own from the holiday.

Military-style spy equipment uncovered

Two Diligence operatives were traced and interviewed by the police. One disclosed he worked for Diligence and was carrying out surveillance on Gerrard to identify his associates. He declined to disclose the identity of his client.

“The anxiety caused by Diligence has been nothing short of horrendous,” Ann would later say in a witness statement. “It has been the cause of stress and sleepless nights.”

Three months later the hidden video camera was found attached to a tree near the entrance to the Gerrards’ estate. A security team employed by the lawyer initially thought they had stumbled on a police surveillance operation, according to Gerrard’s witness statement.

The video equipment was manufactured by the same firm that supplied British police forces, and the camouflage and camera looked like the work of the military. There was a wireless cellular router to transmit live pictures and a video card to store the images. It appeared to have been filming for some time because the card contained 8,900 video files, including more than 1,000 showing people or vehicles arriving and departing over the previous three weeks.

Gerrard and his wife’s vehicles had been filmed more than 200 times. Footage of family, friends and even their postman was also found.

To catch the spies, Gerrard left the equipment intact and arranged for his own secret camera to be mounted in a nearby field. In April 2019, a shadowy figure was filmed creeping up to the hide at night.

Sussex police were alerted. The force carried out a criminal investigation and brought in both the National Crime Agency and the City of London Police. A counterterrorism unit was dispatched to Gerrard’s home to advise him on beefing up his security.

Officers recovered DNA from the surveillance equipment which matched that of a former soldier working for the private intelligence firm.

The force made one arrest and formally questioned a number of individuals. But nobody was charged.

MP’s accusation of ‘aggressive surveillance’

Meanwhile, Gerrard began a fightback against ENRC. He sued Diligence for claims including intrusion and harassment, which Diligence denied.

Diligence argued that its methods were proportionate and necessary to gather evidence in support of ENRC’s high court case and detect whether Gerrard was destroying evidence or tampering with witnesses. However, Diligence gave an undertaking that they would stop spying on Gerrard.

ENRC has also said it was legitimate to hire Diligence. Yates and Bailey did not respond to requests for comment. The case was eventually settled. Therefore, the court did not rule on whether the surveillance was unlawful or what methods were used. However, one high court judge described it as inappropriate.

In parliament last year, David Davis MP accused ENRC of putting a Financial Times journalist investigating the case and a former member of the SFO’s investigation team under “aggressive surveillance”. He said ENRC was “attempting to undermine the freedom of the press and frustrate the legitimate workings of the state. It is immoral, it is intimidating and it is unethical.”

Labour MP Clive Efford said the firm had used lawsuits “to silence and stop” the SFO’s investigation. “We cannot allow that to go on,” he said.

Conservative MP Bob Seely said: “We are getting into very serious territory when the functioning of government, as well as the exposing of truth – and, dare I say, concepts such as justice – is being severely hammered and severely damaged.”

The Brussels operation

Gerrard was not alone in being spied on. In November 2017, an ex-Royal Marine commando who fought in Iraq and Afghanistan, was arrested when he arrived in Brussels on the Eurostar from London.

The 36-year-old from Wales, instantly admitted to the police that he and a team of four other Diligence operatives had come to Belgium to conduct round-the-clock surveillance on Bota Jardemalie, a Kazakh human rights lawyer who had been given political asylum.

Diligence had been employed for years by a bank in Kazakhstan to track down a fugitive billionaire who was alleged to have stolen billions of pounds. Jardemalie was one of a string of people in Belgium and France accused of having links to the fraud.

Jardemalie strongly denies the allegations, claiming they are politically motivated due to her support of opponents of Kazakhstan’s autocratic government. The Kazakh regime had to be propped up by Vladimir Putin’s Russian troops last year amid violent protests.

Data on the ex-soldier’s phone obtained by the police revealed that Diligence’s ex-servicemen had spied through the lawyer’s windows, monitored her family, attached an electronic tracker to her car, hid cameras in head rests and infant seats in rental cars outside her property – and even plotted to rifle through her rubbish.

Officers found 181,000 photos, a long list of GPS coordinates and extensive notes of what the team planned to do. They found that Jardemalie was covertly watched for more than a year by the ex-soldiers, who rented a £2,800-a-month flat within view of her property in an upmarket residential district of Brussels.

In messages, the men discussed “soaking” – a term used for continuous filming – her windows and doorway. They logged intimate details such as whether the lawyer kissed and hugged a male friend in her home. They also considered posing as “local Polish drunks with whisky bottles” to observe her apartment.

Photographs were taken of her son, dog, friends, family and anyone she happened to meet. She was tracked when she made trips to the gym, hairdressers and shops. Records were kept on what she bought and the various outfits she wore.

A plan was drawn up on how they should steal her rubbish and the risks of taking the bin bags back to their hotel room to sort through. In one message, instructions were given about how the bags should be searched. “Product needs to be sifted through and assessed to what is pertinent to the task: receipts, paperwork, meds, clothing, cigarette brand, food types, special dietary requirements noted etc. It all may be useful at some point in the future,” one operative wrote.

Each item of interest in the bins was to be photographed, logged and the images stored on a drive.

The ex-commando was arrested after Jardemalie reported him to the police for following her. “My private life was invaded, and I felt extremely anxious and unsafe,” she said.

A few weeks after the former soldier was detained, Jardemalie says her brother was arrested and tortured by Kazakhstan’s intelligence service.

The firm’s work broke Belgian law because private eyes are required to register with the country’s home affairs department. The police told the ex-serviceman he had not done so, to which he replied: “I did not know this was illegal,” according to the report. Nonetheless, he was released without charge.

Lawyers acting for Diligence said its surveillance was justified because Jardemalie was subject to an international arrest warrant issued by the Kazakh authorities.

The ENRC's former headquarters in London’s Mayfair

Stefan Rousseau/PA Wire

The ENRC's former headquarters in London’s Mayfair

Stefan Rousseau/PA Wire

Testimony from witness paid more than a million

Even once cases get to court, there are more tactics businesses and billionaires can use to help secure victory. In the ENRC cases this involved paying vast sums of money to witnesses who were giving evidence on behalf of the firm. Unlike in the US, paying witnesses in civil cases is legal in the UK.

Cameron Findlay, a former Scotland Yard detective who worked in the private sector as an investigator for a string of Russian clients, had been contracted by ENRC for various jobs. In 2011 he had been called in by the company to assess the allegations of wrongdoing that would later trigger the SFO’s investigation.

Findlay was initially reluctant to get involved in the case against Gerrard. Then ENRC began a legal case accusing him of assisting Gerrard in leaking information to the SFO.

The case was settled in February 2018, with Findlay agreeing to support the ENRC lawsuits in return for a consultancy fee of £380,000 up front and an additional £20,000 per month. By mid-2021 he had received more than £1.1m from ENRC.

Findlay provided detailed testimony against Gerrard. He disclosed evidence of the lawyer’s leaks to the press and SFO, as well as other embarrassing allegations from when they worked together in 2011 and 2012. The judge later expressed concern the money might have tempted Findlay to give false testimony.

Another paid witness was cyber specialist Robert Trevelyan, an ex-forensic computer analyst for UK law enforcement who had assisted Findlay’s investigation.

Trevelyan struck two agreements with ENRC, to assist with the litigation, for £15,000 and then £20,000 a month. By June 2021, he had amassed £700,000 from assisting in the proceedings.

Trevelyan has given witness statements for ENRC and testified in court that Gerrard betrayed his client’s trust by leaking sensitive information to the press. He said the two paid agreements had not required him to provide the statements and had not influenced his evidence in any way.

Findlay and Trevelyan did not respond to requests for comment.

Calls in parliament for a crackdown

A new bill is currently going through parliament which is designed to regulate the private investigation industry for the first time. TBIJ and the Sunday Times’s recent investigations exposing wrongdoing in the sector were credited in the House of Commons when the proposed new law was unveiled in January.

In May last year, the high court cleared the SFO of misfeasance in public office, but the judge did find that the agency had encouraged Gerrard to commit a series of breaches of his ENRC contract.

Gerrard was found to have failed in his duty to his client by leaking to the press and giving inappropriate advice. The judge described Gerrard as a man “so obsessed with making money from his work that he lost any real sense of objectivity, proportion or indeed loyalty to his client”. Gerrard still denies wrongdoing.

A second case is being held this month to decide whether Gerrard and the SFO caused any financial loss to ENRC. The SFO says the Kazakh firm is seeking £20m in damages from the agency. “We deny any liability to ENRC,” an SFO spokesperson said.

Meanwhile, Gerrard has now retired, and the SFO’s long-running investigation into ENRC continues.

The Gerrard case threatened to bust the budget of the SFO. ENRC was accused in parliament of using immoral and intimidating tactics to damage both justice and the functioning of the British state.

David Davis, the former cabinet minister, believes that former members of Britain’s security services should be stopped from commercially exploiting their skills in this way.

“Members of the UK law enforcement and intelligence agencies must now be compelled to give an undertaking that they will not use those skills against the interests of the British state. If they do, their pensions should be in jeopardy,” he said.

“It is deeply disturbing that ex-members of Britain’s security services have been using the covert skills they were trained in at taxpayers’ expense to assist a Russian-backed company under criminal investigation. This is allowing lawfare offensives that undermine British justice to be launched on a scale rarely seen in this country before.”

Last week Labour MP Dan Jarvis, who served as a paratrooper and spent 15 years in the British army, said: “Former British servicemen, who have been trained in covert operations at the taxpayers’ expense to protect the public, should not be commercially exploiting those skills by using them to further the interests of an autocratic state. These veterans run the risk of tarnishing the proud reputation of our armed forces by becoming operatives for a state backed by Putin’s Russia.”

Reporters: Franz Wild, Ed Siddons and Simon Lock

Finance Editor: Franz Wild

Impact Producer: Lucy Nash

Global Editor: James Ball

Editor: Meirion Jones

Production Editor: Alex Hess

Fact checkers: Alice Milliken and Josephine Moulds

Illustrations: Daniel Stolle

Our Enablers project is funded by Open Society Foundations, the Hollick Family Foundation, Sigrid Rausing Trust, the Joffe Trust and out of Bureau core funds. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.

-

Area:

-

Subject: