Hacked evidence and stolen data swamp English courts

A multimillion-pound high court case between an authoritarian Gulf emirate and an Iranian-American businessman has revealed how hacked evidence is being used by leading law firms to advance their clients’ claims.

The case has included allegations that a former Metropolitan Police officer hired Indian hackers and that lawyers from a top City firm held a secret “perjury school” in the Swiss Alps to prepare false witness testimonies about how they got hold of illegally obtained information.

In November the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and the Sunday Times exposed the criminal activities of Aditya Jain, a 31-year-old computer security expert who set up a “hack-for-hire” operation from his apartment in Gurugram, India.

A leaked database seen by the Bureau shows how private investigators linked to the City of London and the Metropolitan Police have been using his gang to target British businesses, government officials and journalists. Jain says he has stopped working as a hacker and denies targeting the people identified.

Many of the hacks appear to relate to UK court cases. Information stolen by Jain’s gang was used as evidence in the London courts and the targets have included several British lawyers. Some of the hacker’s private investigator clients have been contracted by major law firms with bases in the City.

A striking feature of the English legal system is that a judge will accept hacked emails as evidence in court in the interests of justice unless persuaded to exclude it. Peter Ashford, a London solicitor and expert in the admissibility of evidence, claims the English system is “the most liberal”. He added: “Even if you’ve done the hacking, you’ve still got a pretty good chance of getting it in [to the court].”

One of the lawyers engaged in the dispute between the Gulf emirate of Ras al Khaimah and Azima, an aviation magnate based in America, was the prominent anti-hacking barrister Hugh Tomlinson KC.

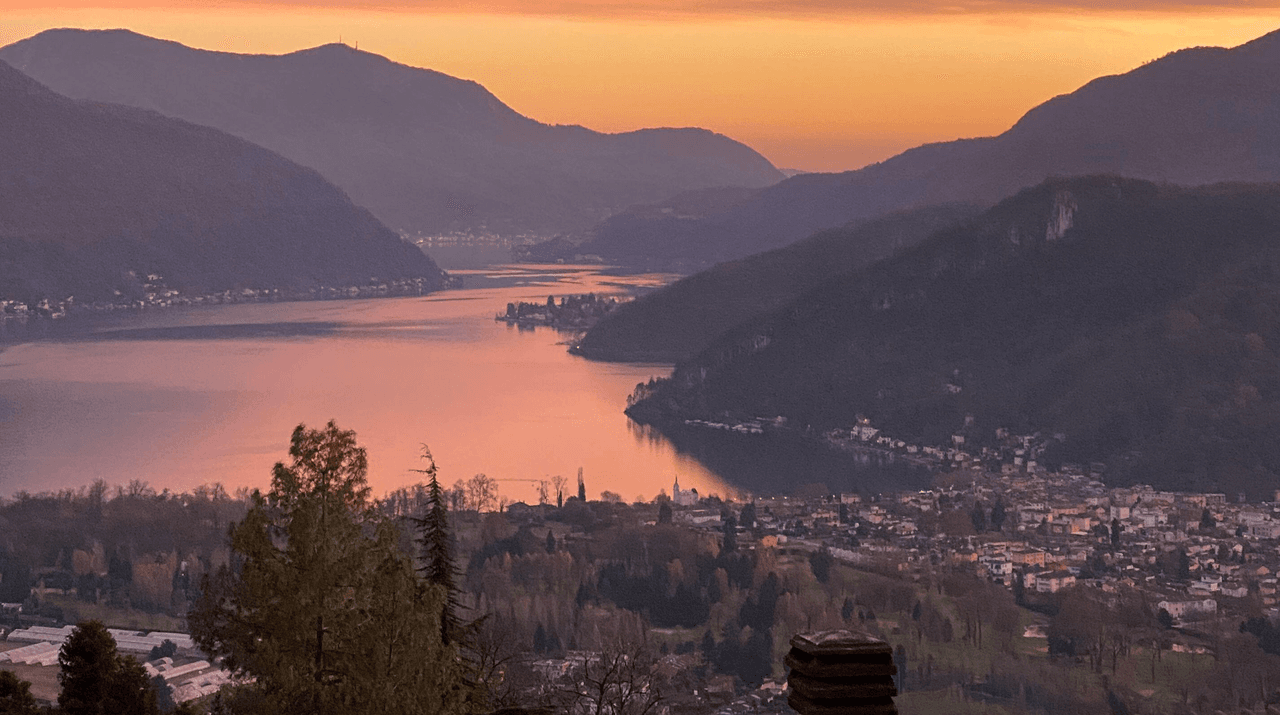

The Sheikh Zayed Mosque in Ras al Khaimah

Aleksandar Tomic / Alamy

The Sheikh Zayed Mosque in Ras al Khaimah

Aleksandar Tomic / Alamy

Tomlinson, who has campaigned against illegal intrusion by journalists as board chairman of the pressure group Hacked Off, used emails stolen from Azima’s personal inbox to prove the businessman had engaged in fraud.

His client, Ras al Khaimah, was locked in a legal dispute with Azima, whose emails had been hacked and dumped on the internet.

Tomlinson told the high court his client’s case was that the emails had been obtained innocently by Ras al Khaimah. He has since said he acted at all times in accordance with his professional obligations and on his client’s instructions when he presented the information.

On 3 August 2015, according to the leaked database, a client called “Nick” instructed Jain’s hack-for-hire firm to target Azima. Our evidence strongly suggests that the “Nick” in the database is Nick Del Rosso, a British former police detective who works on behalf of UK legal firms from his home in North Carolina in the United States.

Azima had fallen out with the Ras al Khaimah Investment Authority, a sovereign wealth fund ultimately controlled by the emirate’s ruler Sheikh Saud bin Saqr Al Qasimi.

Del Rosso had been hired to investigate Azima by the City of London office of the international law firm Dechert, which had been instructed by the investment authority. The Sheikh is said to have been angered by reports that Azima was working with his opponents to draw attention to alleged human rights abuses in the emirate and instructed his staff to “go after” him, according to court papers. There is no evidence that Dechert or its client knew that Del Rosso had instructed Jain to hack Azima.

The leaked database shows Jain’s hacking gang managed to obtain passwords for six of his email inboxes as well as his American Express and Skype accounts.

A year later, tens of thousands of Azima’s emails, personal photographs, voice recordings, videos and WhatsApp messages were uploaded to the internet. Since the information was now publicly available, Ras al Khaimah was free to use it in London’s high court.

Farhad Azima, the businessman at the centre of the legal dispute

AP

Farhad Azima, the businessman at the centre of the legal dispute

AP

The emirate chose Tomlinson to litigate the case and the barrister quoted directly from Azima’s stolen emails in a high court claim filed in September 2016 for his client. There is no suggestion that Tomlinson had any involvement in the hacking of Azima’s emails, but he was aware that they were the product of a hack and would have been professionally obliged to deploy them if instructed to do so.

The claim alleged that Azima had defrauded the investment authority. Almost instantly, Azima issued a counterclaim in the US, accusing Ras al Khaimah of orchestrating the hacking of his personal data.

The two cases would take years to work their way through the courts. In the meantime, on 2 June 2018 according to the leaked database, “Nick” instructed Jain to target Cynthia Beudjekian, an associate of Azima who had exchanged messages with him about the hacking.

Emails stolen from Beudjekian were also later used by Ras al Khaimah in court. Tomlinson told the court her emails had been sent unsolicited by an “anonymous source” to the offices of Stewarts Law – a London law firm that later represented Ras al Khaimah.

The solicitor instructing Tomlinson at Dechert was Neil Gerrard, the global co-head of the firm’s white-collar crime practice. He had initially been assisted by a Dechert colleague David Hughes, who had joined Stewarts Law - hence its involvement in the case.

The two lawyers and another private investigator called Stuart Page – another former Met officer – gave evidence at a January 2020 hearing into the fraud allegations that Azima’s emails had been discovered innocently on the internet by an Israeli journalist. They said they did not know how the information got there.

Their testimony was convincing. The judge dismissed Azima’s claim that the Ras al Khaimah side had orchestrated the hacking. Azima lost his case and was ordered to pay £3.4m in damages.

However, last year Page retracted his evidence in a statement sent to the supreme court. His new testimony alleged that the story about the Israeli journalist had been invented to cover up the fact the emails had been found by an investigator who had commissioned hacking for the emirate.

Page claimed to have been present at a meeting held in Cyprus in November 2018, in which this story he now claimed was false had been agreed with Gerrard and Hughes. He further alleged that he met with Gerrard and the Israeli journalist at a boutique Alpine hotel just weeks before the fraud case against Azima was heard.

He claims they ran through a “mock trial” to rehearse their false witness testimonies. Azima’s lawyers would later describe the gathering as a “perjury school”. In US proceedings, Azima has accused Gerrard and Hughes of orchestrating a criminal campaign to cover up the hacking.

Gerrard, Dechert and Hughes say they did not commit perjury and deny knowledge of the hacking. They say Page had told them the hacked material came from the Israeli journalist and they believed him.

There was no suggestion from Page in his evidence that the emails had been hacked at the instruction of the legal team. In a statement, Dechert said it “did not fund the hacking of Mr Azima or his associates”.

At an appeal court hearing in March 2021 a judge ordered that the hacking allegations should be examined at a trial.

Meanwhile, Tomlinson continued to defend the emirate against the hacking allegations. The barrister argued that Azima’s stolen emails were neither private nor confidential and therefore the businessman could not have suffered distress as a result of the crime.

There is no suggestion that Tomlinson knew who was behind the hacking. He suggested in court papers that Azima’s country of birth, Iran, might be the source of the cyber-attacks.

Tomlinson’s clients, however, were forced to backtrack. The confession by Jain and the allegations about the “perjury plot” had made it harder for Ras al Khaimah to argue that the documents it had used in the original court case had been acquired innocently.

The emirate attempted to withdraw from court proceedings in June and offered Azima $1m in compensation, which he has rejected. In November, a judge ruled that Azima could challenge the original fraud finding.

When approached for comment, Jain admitted that he had hacked people in the past but said he had not done so for several years. He claimed he did not know some of the people named on his leaked database and denied hacking the others listed. “I can say categorically that I have not hacked, launched or attempted to hack any of these people,” he said.

Del Rosso and Ras al Khaimah did not respond to our requests for comment.

Reporters: Franz Wild, Ed Siddons and Simon Lock

Finance editor: Franz Wild

Impact Producer: Lucy Nash

Global editor: James Ball

Bureau editor: Meirion Jones

Production editor: Alex Hess

Fact checker: Matthew Chapman

Our Enablers project is funded by Open Society Foundations, the Hollick Family Foundation and out of Bureau core funds. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.

-

Area:

-

Subject: