Quarter of a million children in Lima exposed to cigarette advertising near school

Like any parent, Luz Magaly Díaz Alvarado worries about her kids.

She recalls a recent trip with her seven-year-old daughter, Emily, to a neighbourhood supermarket in Lima, Peru. Emily’s eyes had been drawn to the sweets and snacks by the tills as they were leaving. As Emily had been good, she was allowed a treat. “She told me, ‘Mom, I want chocolate,’” says Luz. Emily picked out a brightly coloured pack that had caught her eye among the sweets and handed it to her mum.

It was, in fact, a packet of cigarettes.

“It worries me because as a mother, you always try to see the best for your children,” Luz, 31, says matter of factly. “In this case, so that they don’t try to sell your children drugs in disguise.”

“Drugs” might bring to mind stronger, illegal substances but nicotine, which is found in cigarettes and vapes, is one of the most addictive drugs in the world. It’s what gets people hooked on tobacco, which kills more than 8 million people every year.

Luz is no twitchy suburban prude. The San Juan de Lurigancho district, where she raises her young sister and daughter, has a tough reputation. She says there are often people doing drugs on her street at night. “The worst that can happen is that they rob you,” she says.

It might seem surprising, then, that Luz worries so much about cigarettes. But the psychology course that she fits around her full-time job has made her more aware of what her children are exposed to and the influence it has.

“Whenever I go out with my girls, there are always promotions for cigarettes in the stores,” she says. “Next to the candies and gum that children like so much.” In many countries, this kind of tobacco advertising is considered such a health threat that it is banned. But in Peru, the regulations are much looser – you can even advertise near schools, so long as the promotion is contained within the shop rather than outside it.

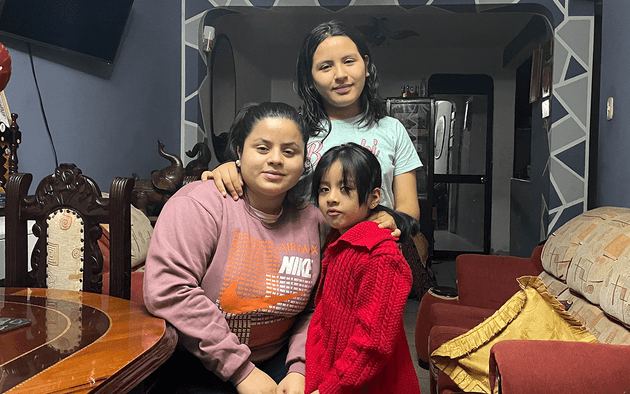

Luz (left) with her sister and daughter in their Lima home

Luz (left) with her sister and daughter in their Lima home

The supermarket where Emily picked up the box of cigarettes is within walking distance of 10 schools, meaning that more than 1,300 students who attend them are at risk of doing the same as she did.

This is not just an issue in Luz’s neighbourhood. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism and OjoPúblico can reveal that nearly a quarter of a million children across Lima are potentially being exposed to cigarette advertising in shops near their school.

Crowdsourced data gathered from across the Lima Metropolitan Area shows an abundance of splashy adverts and displays for cigarettes in shops (see interactive map below). Brands include Lucky Strike and Pall Mall, made by British American Tobacco, and Marlboro, from Philip Morris International. BAT and PMI are two of the biggest tobacco companies in the world.

One store owner said sales representatives from companies who say they work on behalf of Big Tobacco firms visit the shop to tell them where to display cigarettes, including placing them among sweets and snacks.

A draft law proposing a total ban on tobacco advertising is currently making its way through Peru’s Congress. But this has happened before. Over the last decade, various attempts to bring in a ban have failed. Campaigners say this is due to interference from the tobacco industry. Meanwhile, the average age people start smoking in the country has been dropping for decades, and now stands at 13.

Peru is not alone. As tobacco companies talk in the west of a cigarette-free future, they continue to aggressively advertise cigarettes near schools in countries where they can, from Madagascar to Indonesia.

In plain sight

“Chicken, groceries, cigarettes, I sell a little of everything.” Bruno* speaks as he bustles around his bodega serving customers. Bodegas are Peru’s answer to the corner shop. Like many, Bruno’s is a sliver of a shop, squeezed between houses and providing essentials to locals.

These small, independent convenience stores are a part of the fabric of everyday life in Peru. It is estimated that there are more than 500,000 dotted throughout the country. And it is in the bodegas of Lima, as well as in small chain stores and supermarkets, that schoolchildren like Emily encounter cigarette adverts. Crucially, the promotion of tobacco products within 500 metres of a school is illegal in Peru – unless the advertising is done inside.

Bodegas like this one are part of everyday life in Lima

All shop photos provided by data collectors

Bodegas like this one are part of everyday life in Lima

All shop photos provided by data collectors

The Bureau’s data shows that nearly 600 primary and secondary schools in the city have cigarette advertising within 500m of their front gates. This means that nearly a quarter of a million students in Lima alone could be exposed to cigarette advertising around their school.

The Bureau has crowdsourced numerous photographs of these adverts, as well as those showing packs of cigarettes next to sweets or snacks, or in plain sight of children.

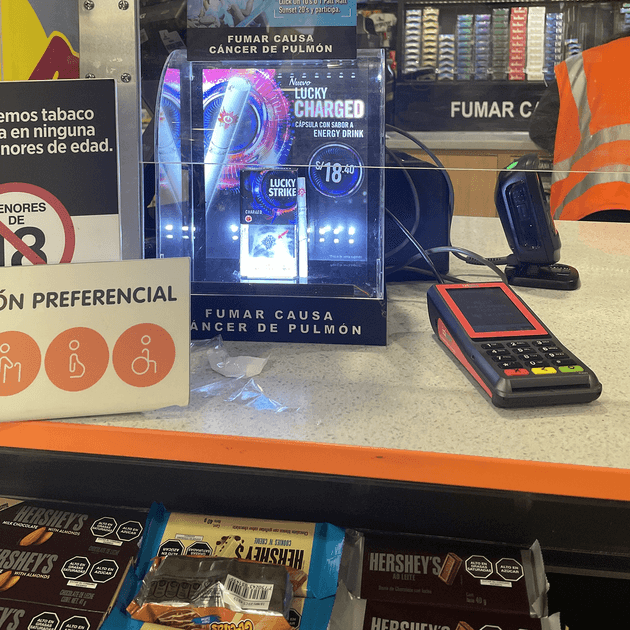

In these photographs, submitted by Lima residents, are posters popping with vivid pinks and cool blues whose catchy slogans advertise Lucky Strike’s energy drink-flavoured cigarettes, as well as sleek displays of Pall Mall cigarette boxes right by the cash register.

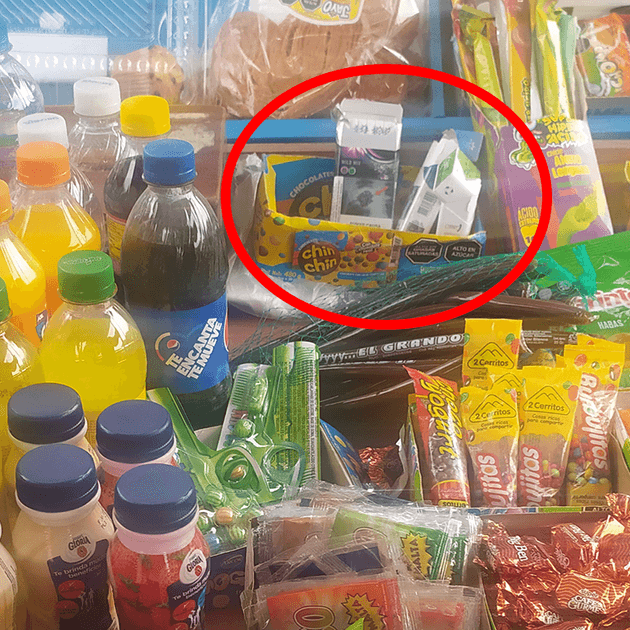

In other shops are arrangements that could lead a child to make the same mistake as Emily: cigarette boxes spread in a rainbow of colours, surrounded by packets of sweets, chocolates and crisps; or open packs of cigarettes – most likely for people who want to buy singles – nestling within easy reach of children among bubblegum, cakes and soda.

The most frequently advertised brands were owned by BAT, with nearly two thirds of our recorded instances of advertising within 500m of schools. More than a quarter were for its Lucky Strike cigarettes, while a fifth were for Pall Mall. PMI brands also featured prominently, with Marlboro and L&M being advertised near schools in dozens of cases.

BAT told the Bureau that its products are for adults only and should never be used by those who are underage. It said it markets its products responsibly, in accordance with local laws and internal company standards, and provides training to emphasise the importance of complying with those standards and minimum-age-of-sale laws.

PMI referred us to a statement from May, when a spokesperson said that the company “is clear that youth should not use any tobacco or nicotine-containing product” and works “to prevent our marketing and products reaching this audience”.

They added: “We engage with a wide group of stakeholders on this issue, including independent retailers and governments. We monitor compliance – including from third party vendors – and report publicly on our progress annually.

“PMI investigates all potential breaches of our global marketing practices and if verified we will ensure corrective action is taken.”

Our research supports a 2019 study by Johns Hopkins University and Peruvian anti-tobacco organisation COLAT, which found similarly aggressive marketing techniques aimed towards young people.

In one bodega, packets of cigarettes were displayed among confectionary and fizzy drinks

In one bodega, packets of cigarettes were displayed among confectionary and fizzy drinks

It is not just in bodegas where cigarette advertising is prevalent. Branches of Tambo, a chain of around 400 stores in Peru, hosted some of the most prominent displays we found. These included big, illuminated ads pushing flavoured cigarettes, which have been shown to particularly appeal to young people and in many countries are banned altogether. Some of the stores – and the glowing cigarette ads – are directly over the road from a school’s front gates. Tambo did not reply to the Bureau’s requests for comment.

Getting the next generation hooked

In his bodega, Bruno stocks various cigarettes including Golden Beach, L&M, Lucky Strike and Pall Mall. He is somewhat reluctant to talk about his relationship with cigarette suppliers but does say they advise him on how to display cigarettes.

Bruno says that distributors who sell Lucky Strike and Pall Mall on behalf of BAT tell him: “‘Put it like this, you will sell more … in the front, next to the cookies.’”

“They say, ‘Your competition sell three times as much as you do, they put the cigarettes on display,’” he says, adding that distributors acting on behalf of PMI also come to his store and give some recommendations on how to display cigarettes.

Another bodega owner told the Bureau that cigarette distributors visit them every 15 days and put the adverts in place themselves.

The Bureau has found that some shops within 500m of schools are displaying cigarette advertisements on the outside of the store, even though this is illegal.

Bruno says that when a new brand enters the market, posters are put up outside the store and the guidance he receives about displaying products intensifies.

A Bureau reporter posing as a shop owner spoke to the company that supplies Bruno’s bodega with Lucky Strike and Pall Mall cigarettes. The company’s employee said it was the sole official distributor for BAT brands in Peru but that BAT also had its own sales representatives. They said the stores would be assigned a BAT representative who would monitor sales, visit the shop and advise on where displays will best attract attention.

Our reporter was also told by a distributor of PMI cigarettes that PMI is in charge of supplying displays for its cigarettes and that it works directly with supermarkets in Peru.

“This is something organised, something that comes with a directive,” says Carmen Barco, executive director of Peruvian anti-drug abuse organisation CEDRO. “The products are located here, the advertising is located here to normalise smoking to children. So that the children feel, see, believe that this is something normal.”

A case of cigarette boxes surrounded by sweets, chocolates and crisps

A case of cigarette boxes surrounded by sweets, chocolates and crisps

“It’s a major problem across the country,” says Barco, who has worked in tobacco control for over 30 years. “From big cities to rural towns, we see the same advertising.”

The Association of Bodega Owners of Peru told the Bureau: “We place the information on the availability of these products, inside our businesses, in strict compliance with the law.”

It added: “We believe in the freedom that consumers have to purchase their products in an informed and responsible manner. We understand the concern to protect minors from these products, but these products are already prohibited to minors and considering hiding or hiding them from adults is a nonsense that has shown to be ineffective in other countries.”

While the legal age to buy cigarettes in Peru is 18, the average age Peruvians start smoking is five years younger. The Pan American Health Organization says there is evidence that “the tobacco industries enhance their sales tactics by focusing on children and adolescents”.

This situation concerns Jemima Rodriguez Peraltilla, a 21-year-old secondary school teacher who lives in La Victoria, a commercial district of Lima.

“When I studied at school, it was not so common [to see young people smoking],” says Jemima. She says it’s much more popular now and blames advertising, which she says is “everywhere we go … in stores, in kiosks, on every corner, you can see a lot there. I feel sad and worried because this is going to affect all of us in the future.”

Jemima would like to see cigarette advertising done away with. She’s not the only one. Parents, teachers and policy makers all feel that more needs to be done to protect young Peruvians. One teacher who works in the area Luz lives in says children can buy cigarettes easily from any shop or store.

An illuminated cigarette display above a shelf of chocolate bars at the point of sale

An illuminated cigarette display above a shelf of chocolate bars at the point of sale

“Unfortunately, you see minors smoking on the street more and more,” says congresswoman and former president of congress Lady Camones Soriano. “The current law has not only been insufficient, but its control is almost impossible.”

Time to act

Many countries around the world have imposed a total ban on cigarette advertising, as recommended by the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. This includes outlawing the display of tobacco products at the point of sale – near the cash register. There is hard evidence that these bans reduce the chances that young people take up smoking. So why is the law in Peru not providing greater protection for its citizens?

Even though Peru is a signatory of the Framework Convention and had promised to introduce a total ban on advertising by 2010, it still has not banned the display of cigarettes at points of sale, nor adverts that are inside a shop.

Camones says the previous attempts to ban tobacco advertising have been “questioned, postponed and shelved” without taking into account “the abundant scientific evidence that supports that this measure is important”.

Flavia Radovic, president of anti-tobacco organisation COLAT, says it has been pushing for a ban on tobacco advertising in bodegas and supermarkets for the last decade, but “the tobacco industry has been very active in opposing it, or lobbying against it, to ensure these bills don’t succeed”.

“Every time any bill is presented,” she says, “the congressmen and women who are under the orbit of the tobacco lobby vote against it.”

Once again, a bill proposing such a ban is being presented to Peruvian Congress.

If passed, the bill would effectively prohibit all of the kinds of advertising reported by the Bureau. Created with the support of COLAT, it also recommends measures that would put a lid on the kind of industry interference that critics say has dogged tobacco control efforts in Peru for years.

“We want to prevent the development of new generations of addicts,” says Camones, who is presenting the bill. “We could not remain on the sidelines.”

Luz is realistic about the future. “My daughter is not going to be a girl forever,” she says, recognising that she can only protect her for so long. “She’s always going to have the fact that somebody might offer her a cigarette.”

Can this bill succeed where others have failed? Will it hail a new era in Peru’s relationship with tobacco? Luz is sceptical. “The government does not do much for its people.” And as the country swears in a new president following political turmoil and an “attempted coup”, it is unclear what the future holds for the new bill or those that support it.

But Camones feels that she and her congressional colleagues have a responsibility to the people of Peru to act now. “If something is not done today, we will have serious consequences.”

* Name has been changed

The Bureau thanks all the volunteers in Peru who collected data for this investigation.

Reporters: Paul Eccles, Matthew Chapman and Chrissie Giles

Additional reporting: Maria Cervantes and Fin Johnston

Data lead: Charles Boutaud

Data visualisation: Terence Eden

Global Health Editor: Chrissie Giles

Global Editor: James Ball

Editor: Meirion Jones

Production Editors: Alex Hess and Emily Goddard

Fact Checkers: Robert Soutar and Niamh McIntyre

Illustration: Emilio Cruañas Pérez/OjoPúblico

Our reporting on tobacco is part of our Global Health project, which has several funders. Our Big Tobacco project is funded by Vital Strategies. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.

-

Area:

-

Subject: