Inside the global hack-for-hire industry

In a quiet alcove of the opulent Leela Palace hotel in Delhi, two British corporate investigators were listening intently to a young Indian entrepreneur as he made a series of extraordinary confessions.

The 28-year-old computer specialist Tej Singh Rathore described his role as a player in a burgeoning criminal industry stealing secrets from people around the world. He had hacked more than 500 email accounts, mostly on behalf of his corporate intelligence clients.

He believed the smartly dressed British investigators were in India to employ a “hack-for-hire” organisation such as his own. In fact, they were undercover journalists infiltrating the illegal hacking industry.

Rathore paused briefly as guests in colourful saris swept past the trio’s table before confiding that he had broken into a number of email accounts on behalf of UK clients. In fact, he claimed, the majority of Britain’s private investigation firms employ Indian hackers.

“The British and the whole world … are using Indian hackers,” he said.

The use of the Indian underworld to break into email accounts and smartphones has become a practice that has been proliferating for years. British investigators have been able to commission “hack-for-hire” firms with little fear that they will be prosecuted for breaking the UK’s computer misuse laws.

An investigation by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and the Sunday Times revealed the contents of a leaked database from inside one of the major “hack-for-hire” gangs. It shows the extent of illegal computer hacking across the City of London for corporate intelligence companies targeting British businesses, journalists and politicians.

But this gang is not the only one. The undercover reporters made contact with a series of Indian hackers who were secretly filmed speaking openly about their illicit work and their underground industry’s nefarious influence in Britain.

It is illegal to commission hacking from the UK, a crime punishable with a prison sentence of up to 10 years. There are similar laws in India, where unlawfully accessing a computer carries a jail sentence of up to three years.

But the hackers had no fear of being found out. One laughed when asked if any Indian hacker had been caught. “Not even a single [one],” he said.

The roots of India’s illicit trade

One of the striking aspects of our investigation is that the very people who set themselves up as the good guys are all too often the bad guys.

In recent years there has been a trend for computer security firms to pretend to be training “white hat” hackers so their knowledge can be used to protect clients from online attacks. In reality, however, they are being readied for the dark side.

There is plenty of money to be made from breaking into private email accounts, and plenty of clients willing to pay. This is how the Indian hacking industry began.

One of the industry’s founding fathers was a firm called Appin, set up in Delhi more than a dozen years ago supposedly to train a new generation of “ethical” hackers who could help safeguard individuals and businesses from cyberattacks.

However, the firm, now defunct, is alleged to have secretly established a lucrative sideline taking cash from clients around the world to hack individuals. These clients are said to have included corporate intelligence companies based in Britain.

India was a particularly attractive proposition for the investigators. It was not just that India’s enforcement of computer misuse rules was light touch; the commissioning of crimes in a faraway country with a different jurisdiction greatly reduced the risk that the investigators would be caught or prosecuted.

Among the “ethical” hackers trained by Appin was Aditya Jain, whose secret database revealing that he hacked Qatar’s critics is also exposed today by the Bureau and Sunday Times. The Gulf state is said to have been one of Appin’s customers, according to one ex-employee who spoke to this newspaper’s undercover reporters. This is denied by Qatar.

Appin’s days at the forefront of the illegal industry came to an end when its activities were exposed publicly. In 2013, Norwegian cybersecurity experts linked Appin to wide-scale cyberattacks that had been directed at more than a dozen countries.

A year previously, Appin had been accepted onto a global entrepreneur programme run by the British government's trade department.

The department said it had been unaware of any allegations against Appin when the firm was accepted onto the scheme.

10,000 hacked email accounts

As Appin grappled with hacking allegations in 2013, its well-trained former employees scattered like seeds and set up new firms to utilise their freshly acquired talents in the computer dark arts. This created a more diversified Indian hacking industry.

Several set up offices in Gurugram, a city of high-rise glass buildings criss-crossed by dusty pot-holed roads on Delhi’s south-western outskirts, where some of the biggest technology companies in the world, including Meta, Google and Twitter, have offices.

Jayant Bahel/Alamy

Jayant Bahel/Alamy

One of Appin’s successors was a company called BellTroX, which became the key new player in the hacking industry. The company’s director, Sumit Gupta, who previously worked at Appin, was placed on a US Department of Justice wanted list after he was caught operating a large-scale hacking operation with two American private detectives.

In 2020, the Canadian cybersecurity watchdog, Citizen Lab, published evidence that the company had hacked more than 10,000 email accounts, including those of British lawyers, government officials, judges and environmental groups, on behalf of its clients.

Citizen Lab had found that LinkedIn networking profiles connected to BellTroX had hundreds of endorsements from corporate investigators. The company stayed in business, however, and last December, Meta, Facebook’s parent company, was forced to delete 400 accounts run by BellTroX from Facebook.

The revelations are said to have caused panic in Western corporate intelligence circles because so many of the investigators had used Indian companies to hack emails for their clients.

Undercover operation

Since hacking is illegal, the industry is highly secretive and it is rare that any information leaks about the illicit practices. We began an undercover investigation to talk to the hackers themselves.

Two reporters created a fake corporate investigation company based in Mayfair called Beaufort Intelligence and posed as recently retired members of Britain’s secret services.

The reporters then messaged suspected hackers in India saying they were seeking to employ a cyberinvestigator to help them gather information on their client’s targets. When the replies came back, they flew to Delhi in February.

One of the first hackers to respond was a man calling himself “Mahendra Singh”. His LinkedIn networking page was brazen: his skills were listed as “android hacking”, “mobile phone monitoring” and “email tracing and penetration”.

The reporters met him for coffee at the Leela Palace hotel just outside Delhi’s diplomatic enclave.

His first admission was that he was using a false name. He was in fact Tej Singh Rathore. There would be many more confessions.

The notorious double murder

First, Rathore explained how he had become a hacker. He said he had switched to an “ethical hacking” course while studying information technology at the Rajasthan Technical University in Kota because he recognised it was an “emerging industry”.

After graduating with a first-class degree in 2014, he had taken a job at a cybersecurity company based in Amritsar, the north-western Indian city, where his boss let him in on a secret. Computer “offensive work” – the term used for hacking – was much better paid than “defensive work” protecting systems, his boss told him.

The choice was clear. Rathore struck out on his own and wrote to corporate intelligence companies on LinkedIn touting his hacking skills. The work that came in would transport him into a world of marital disputes, corporate espionage and murder.

His first job, he says, was for a winemaker in New Jersey. The winemaker wanted Rathore to hack her husband’s email to find out about his financial situation before she divorced him.

One particularly lucrative assignment was from a Belgian equestrian who commissioned him to hack a wealthy stable owner in Germany. “I charged my client from Belgium $20,000 for [breaking into] a single email [account],” he recalled.

He also became involved in one of Canada’s most notorious double-murders. In December 2017, the billionaire Barry Sherman and his wife, Honey, had been found dead next to the indoor swimming pool in their Toronto home. They had been strangled with leather belts.

Billionaire Barry Sherman and his wife Honey were killed in 2017. An Indian hacker, Tej Singh Rathore, was hired to crack Sherman's emails

Carlos Osorio / Toronto Star

Billionaire Barry Sherman and his wife Honey were killed in 2017. An Indian hacker, Tej Singh Rathore, was hired to crack Sherman's emails

Carlos Osorio / Toronto Star

As the investigation into the murders continued, Rathore was told to break into the email of Kerry Winter, Sherman's cousin

Carlos Osorio / Toronto Star

As the investigation into the murders continued, Rathore was told to break into the email of Kerry Winter, Sherman's cousin

Carlos Osorio / Toronto Star

Sherman was Canada’s 12th richest man and the murder caused a sensation. Soon after, Rathore received a call from a private investigator who wanted him to hack the dead man’s email account. Rathore is not sure who the investigator was working for but he believes the ultimate client may have been one of the suspects in the case.

He failed to break into Sherman’s email but his work was not finished. He was then paid to investigate another suspect in the case: Kerry Winter, Sherman’s cousin.

There was no evidence that Winter had any involvement in the crime but he had been embroiled in a decade-long lawsuit seeking to force Sherman to hand over a chunk of his fortune. The court had dismissed the claim shortly before the billionaire was killed.

The hacker said his investigation uncovered personal details about Winter and his family that made the client “very impressed”. The double murder has still not been solved.

Rathore also hacked the mistress of a Hong Kong-based diamond dealer to find details of her “sexual activities”. At the time, Rathore said, she was blackmailing his dealer client by threatening to tell his wife about their affair unless he paid her a large sum of money.

Law firms were often the ultimate clients of the private investigators commissioning his hacking work, he claimed. He said, on at least one occasion, lawyers had lied to a judge about the true origin of the hacked information they were relying on in court.

Within a few years, Rathore’s hacking business was booming. He says he charged between $3,000 to $20,000 for each email account he hacked and had established corporate intelligence clients in North America, Hong Kong, Romania, Belgium and Switzerland. His next move would be to enter the lucrative illicit British market.

Stealing passwords and surveillance

In many ways Rathore is everyone’s nightmare. His simplest trick is to send his victims phishing emails containing fake Facebook login pages in the hope that this will dupe them into surrendering their username and passwords.

He claims that he can produce a Facebook login page to “such a level of detail” that it is indistinguishable from the real thing. “Most of the time the target gives us their own password,” Rathore explained. “They think the site is legitimate and the site is not legitimate, and they give the password on their own. We are not a god, so we can’t predict the password. Always, they give.”

Rathore often passes the login details to the investigator client, which allows them to access the victim’s private information. Since many Apple and Google account logins often require only a single password, the investigator can swiftly seize everything the victim stores in the cloud.

He said: “You can directly access email, you can directly access the drive, you can directly access calendar, you can directly access contacts and you can directly access [their] location.” He said victims’ photos and recent WhatsApp messages can also be stolen.

Before approaching his victims, he researches their personal life looking for details about families, relationships, upbringing, children, wealth and holiday destinations. He does this using automated software to scour the internet for scraps of information about the victim and monitors his targets’ WhatsApp account to establish the time of day they are usually online.

“We have surveillance on you for a week, for two weeks, for three weeks or maybe for a month,” he said. This helps him to be more convincing when posing as an acquaintance of the victim.

It is a “psychological game”, he said. One example he gave was of an Indian man who had hired him to hack the email account of his air hostess girlfriend because he suspected she was cheating on him.

Since the girlfriend was “a bit of a drinker”, Rathore analysed her social media and found a photograph of her at one of her favourite bars. He then posed as the bar’s owner and emailed the picture to her. The email said: “Hi, I want to share that picture [with] you so you can save it to your phone. And when you come back, just show the picture at the doorstep, and you will get some discount.”

When she clicked on the picture, malicious software downloaded, allowing Rathore to upload her private information. “It worked,” he recalled. “I got the email account.”

For some clients he offers to upload the hacked information to a secure shared online database so they can read it. He can also film himself as he tours a victim’s mailbox.

“I can make a video. I just open the account, go onto every mail, every attachment, making a video for the complete thing and send to you,” he explained.

An illicit British market

Rathore alleged that UK companies had been employing Indian hackers for more than a decade and were mostly the clients of the two big players in the industry, Appin and BellTroX.

He was first hired by British corporate intelligence companies in 2019 after he contacted them on LinkedIn. It was a rich vein for the hacker. “There are lots of companies in the UK and they are looking for the same kinds of [hacking] services,” he told the undercover reporters.

In 2020, he was commissioned to hack Ben Duckworth, a former manager at the Scottish craft beer company Brewdog who had been publicly critical of the company. After leaving Brewdog, Duckworth had set up his own brewery called Affinity Beers, which is now based in Brixton, south London.

Rathore posed as a brewer wishing to buy into Affinity and sent Duckworth an email. “I targeted him [saying], ‘I’m an Italian businessman, I want to invest in your company and I want to get a 40% stake,’” he said.

Duckworth clicked on the phishing email, which gave Rathore the password to his account. “After I got access to his email, I just transferred the credentials to the client and whatever they want to do, they do,” Rathore recalled.

Rathore said he was commissioned to hack the email address of a former manager at Brewdog who had set up his own brewery, Affinity

Chris Ratcliffe/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Rathore said he was commissioned to hack the email address of a former manager at Brewdog who had set up his own brewery, Affinity

Chris Ratcliffe/Bloomberg via Getty Images

When the Sunday Times and the Bureau informed Duckworth of Rathore’s claims, the brewer said he was unaware he had been hacked. Rathore does not know who the ultimate client was as he dealt only with the private investigator, whom he declined to name. Brewdog denies any involvement in the hacking and there is no evidence the company was behind the attack.

In another case, Rathore was hired by a private investigator on behalf of a client on the outskirts of north London who suspected his wife was having an affair. “The husband wants to get into [her] email account and Facebook account,” Rathore recalled. “He wanted to tell how much time she is chatting with a … single person [and] who is that person.” Rathore said he hacked the Facebook account and passed the details to the client.

Rathore was cagey about naming his private investigation clients, but he did mention one: a London corporate intelligence company that employs former British spies and members of the armed services. He says it asked him to access the “overseas bank account details” of a Belarusian hotel owner in April 2020.

The company denies the allegations. However, its website says its investigators can locate online accounts and emails and it uses clever new software to secretly analyse the “dark” corners of the internet. Rathore said his efforts to access the bank account details were unsuccessful, but he carried out “dark web” searches on the hotel owner.

Rathore was not just a hacker. He was also hired to do a reputation management job for a British politician. In early 2021 he says he was paid £1,500 for a month’s work by a London-based corporate intelligence company acting for Matthew Gordon-Banks, 61, the former Conservative MP for Southport, to bury an embarrassing story on a political blog.

To make the story disappear down the Google rankings Rathore spent a month posting positive content about the politician, passed to him by the corporate intelligence firm.

The work ended in April last year and was apparently successful. However, bad news has a habit of rising to the surface and Rathore’s work ultimately failed. The offending story can still be found with a Google search for the ex-MPs name.

Last week Gordon-Banks said he had never heard of Rathore and denied using the services of a reputation management company.

When approached for comment last month, Rathore claimed he had only “hacked 100 times”. “I was blowing my own trumpet,” he said.

Cloning the NHS website

Another hacker who was keen to work for the undercover reporters was Utkarsh Bhargava. He was based in Bangalore so the reporters held long Zoom calls with him from their hotel room in Delhi.

Bhargava said he had worked as a hacker for almost a decade. He started out studying computer science at India’s Institution of Engineers and had instantly taken a job hacking with a company in Delhi.

He describes the company – which recruited all 17 students from his cybersecurity course – as “a homeland security company” for the Indian government. “You are not going to find any details about it over the internet, they work with the Indian government very closely, they do all their offensive [hacking] work,” he told the reporters.

At the time, the homeland security company's training arm was Appin and Bhargava did a year’s instruction in hacking computers with the notorious company. He particularly remembers Appin’s hackers working for clients in the Middle East where they stole “anything and everything”. He said: “They were in Qatar, they were in Dubai, they were in Bahrain. They were in Kuwait, they were in Saudi, they were doing so many things.”

After completing Appin’s finishing school, Bhargava said he was ordered to start a series of cyberattacks on the governments of Turkey, Pakistan, Egypt and Cambodia at the behest of the Indian state. The targets were typically secret documents and files located in other country’s ministries. One of his colleagues was trying to break into the Canadian government’s computer systems.

“We were not allowed to have questions. It was just, ‘Hey, this is the target. You have got three months of time. Do whatever you want to do – we need results.’ That’s how it works … They will say, ‘Hey, this is the ministry of this particular country, we need this data.’

“Our job was to get the data dump and hand it over to the [Indian] agency … [The target] can be the external affairs ministry, it can be home, it can be defence, it can be finance. It depends what kind of intelligence they are seeking.”

Bhargava left the homeland security comapny in September 2016 to join the booming commercial hacker-for-hire sector and set up his own company, Aristi Cybertech Private Limited, based in Bhopal, to take on private hacking jobs.

He charges between $10,000 and $15,000 per job and works for French, Austrian, German, Italian and Thai clients. One Austrian client, with the surname Muller, commissioned Bhargava in the summer of 2020 to hack passenger lists from the airline EgyptAir.

Bhargava recalled: “That was super easy actually. If you look into EgyptAir’s IT info even today they don’t care much about IT. They don’t have proper security configuration, there is no proper architecture that’s available ... It was easy going.”

Bhargava had a range of inventive methods to dupe victims into giving up their passwords or downloading malware onto their devices. If one of his UK targets had a medical problem, for example, he proposed creating “an exact lookalike” of the NHS website and telling them they needed to log in to order medication.

“I am going to clone the NHS [login page] for you and share the link with you. You will click on it, you will see that’s National Health Service,” he said.

He was confident that he would never be prosecuted for any of this illegal activity. “No one is trying,” he said when asked about the enforcement of computer misuse laws in India. “They are the police, they are not professional IT people so they don’t understand these things.”

Pegasus spyware

Bhargava even claimed to have access to Pegasus spyware – one of the world’s most powerful cyberweapons – which can be covertly installed on target mobile phones enabling the hacker to download all the device’s content.

Pegasus, which was developed by the Israeli surveillance company NSO Group, infects iPhones and Android phones and can extract encrypted messaging apps like WhatsApp, Signal and Telegram. It can also give a hacker remote control of a phone’s cameras and microphones.

In recent years authoritarian governments have used this software against human rights activists, journalists and lawyers. The NSO Group insists its spyware is only sold to nation states to protect their security.

However, Bhargava said he discovered the Pegasus source code in 2019 and claimed that he and a number of commercial hackers were using it for their paying clients.

He described it as a game-changer. “After getting the … access you will have complete control,” he said, “you are free to do whatever you want.” He said Pegasus allowed a target’s location to be constantly monitored. “If their GPS location is turned on you can track them in real time,” he explained.

Later Bhargava sent the reporters a copy of the Pegasus code he was proposing to deploy on their behalf. We passed the code to Etienne Maynier, a cybersecurity researcher at Amnesty International's Security Lab, who confirmed it was, indeed, a “deconstructed Pegasus code”.

To make it operational, Maynier said, a hacker would need to repackage the code and build an “online operations centre” that would receive the hacked data. This is exactly what Bhargava said he was proposing to do for the undercover reporters.

Last month, Bhargava said he was “a cybersecurity professional working on the cyberdefence side where I help organisations protect their digital assets”. He added: “I have nothing to do with the hacking.” The NSO Group denied the Pegasus code had been leaked.

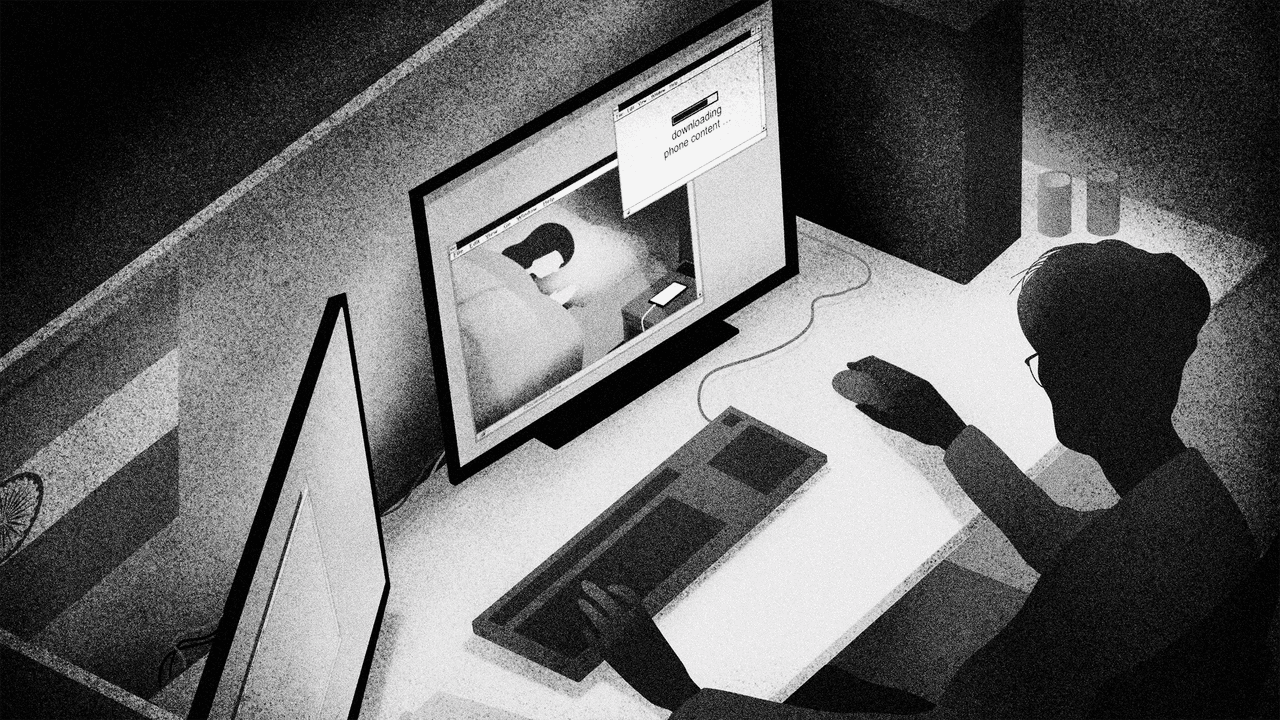

Spying on phones by night

The snag with spyware for the hackers is that the victim’s phone heats up and becomes noticeably slower when its contents are being downloaded. So the hackers study the victim’s routines to identify periods when they are not using their phone.

“We have to modify things for their lifestyle,” Bhargava explained. For most targets he recommended hacking their phones in the small hours. “The data cloning is done in the night … at maybe 2am to 3am. At that time they will be in deep sleep and don’t go into their phone.”

With devout Muslim targets – such as the employees of a Middle Eastern company he had hacked – there was another window of time when they might not be using their phone. “We used to attack them on Friday during the prayer times. At that time no one was there, they were busy with the prayers – and we were doing our job.”

Rathore too wanted to deploy Pegasus. He claimed he had made contact with a corrupt Israel-based insider working for NSO Group and he was negotiating access to Pegasus so he could offer a powerful new service to his clients. “I hope in three or four months the partnership will be done and I can give that service also,” he said.

The NSO Group denied Pegasus had been sold to Rathore.

Meeting the ex-army intelligence chief

In the garden of the five-star Marriott Hotel next to Delhi airport’s runway, the two undercover reporters sat across a table from a man who knew all about state-sponsored cyberattacks.

Brigadier Ram Chhillar had been the commander of the Indian army’s “trans-frontier” intelligence unit and had overseen its “sensitive” cyber division until he retired in 2014. He had set up a company in Gurugram called Phronesis.

The brigadier’s spy background made him suspicious of the undercover reporters’ claims to be former British agents. He attended the meeting with a colleague who made a point of stressing that the company did not do hacking, “cyber stealing” or obtaining “bank statements”.

The brigadier did admit, however, to mining the “the deep, dark web” to obtain people’s personal data. “Insurance companies have had their breaches so that dataset which is there also includes personal data of you and me. So all that is available,” Chhillar told the reporters. “It adds to your investigations.”

He claimed his company were experts at finding this type of data and they could even conjure up people’s computer passwords from the dark web. “[Passwords are] available at a cost … that’s part of intelligence gathering,” he said. His associate added: “It takes time but yes, it is done, it is being done every day, everywhere.”

The two men did not explain why their customers would wish to buy someone else’s password.

Chhillar said the firm had several UK-based corporate intelligence clients. His colleague said he played golf with the managing directors of two leading London-based corporate intelligence companies. “I drink with them, they’re my old time buddies,” he said.

Last month Chhillar failed to explain why he provided clients with targets’ passwords but insisted that he would not “indulge or support” hacking emails or “any such illegal activity anywhere in the world”.

Hacking factory

Before leaving India the undercover reporters attempted to contact another alleged hacking company named CyberRoot.

The firm is alleged to have received $1 million from a former British police officer turned private investigator called Nick Del Rosso to hack the opponents of the Gulf emirate Ras al Khaimah, according to a case in London’s high court.

CyberRoot’s office is on the fifth floor of a glass building on Gurugram’s outskirts. The receptionist seemed flustered when the two reporters walked into the office and said they were from a London corporate intelligence company.

She went away and the reporters popped their heads around the door she had left ajar. Inside was a large darkened room with banks of computers in lines. Young employees, some wearing hoodies, were hunched over keyboards punching keys intensively.

Was this an Indian criminal hacking factory in action? The receptionist came back to say her boss was unavailable. This was not the kind of place to welcome unannounced guests.

Last month, CyberRoot denied involvement in hacking and said the payment from Del Rosso was for cybersecurity and other computer-related services. Del Rosso denies commissioning hacking.

This story was updated on April 28, 2023.

The Bureau newsletter

Subscribe to the Bureau newsletter, and hear when our next story breaks.

Reporters: Franz Wild, Ed Siddons, Simon Lock, Jonathan Calvert and George Arbuthnott

Enablers editor: Franz Wild

Impact producer: Lucy Nash

Global editor: James Ball

Bureau editor: Meirion Jones

Production editor: Alex Hess

Fact checker: Alice Milliken

Illustrations: Daniel Stolle

Animations: Rhodri Andrews

Our Enablers project is funded by Open Society Foundations, the Hollick Family Foundation, the Sigrid Rausing Foundation, the Joffe Trust and out of Bureau core funds. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.

-

Subject:

-

Area: