Paid protesters, free lunches and backroom chats: Inside the menthol lobbying machine

The first course was already on the table by the time the diners found out that the $40,000 lunch had been paid for by a tobacco company.

It was December 2, 2021, the third day of the annual gathering of the National Black Caucus of State Legislators, a 700-strong group of Black lawmakers and their staff from across the US. Bouquets of orange and white flowers decorated the 50 or so tables in the windowless conference room of the Marriott Marquis, an upscale hotel in downtown Atlanta.

For the cigarette maker Reynolds American, it was a chance to have the ear of elected state officials from New York to California. And given the scale of the threat facing the company, the lunch was almost certainly worth the price.

As the guests spooned dressing over their salads, a retired deputy police chief, Wayne Harris, stood up from his chair on stage to give his presentation. He wore a dark suit, glasses and a buzz cut. He spoke without notes, with the composure of someone who seemed to have said some version of these words many times before.

“This is not a conversation trying to get anyone to run out and buy a pack of Newports,” Harris began, referring to Reynolds American’s best-selling product, Newport menthol cigarettes. “This is us as police officers here today to talk to you about how bad policy not only impacts our industry but also impacts our communities.”

The clear impression was that Harris was not just talking about any “bad policy”, but specifically the country-wide debates on whether menthol cigarettes, the flavour of choice for the vast majority of Black smokers, should be banned.

Reynolds American, which is owned by the UK-headquartered British American Tobacco, sells billions of dollars worth of menthol-flavoured cigarettes every year. But more and more cities are either considering banning or have already banned menthols, which are seen as a gateway to getting young people hooked on cigarettes. The company told the Bureau it believed that “regulating menthol cigarettes differently than non-menthol cigarettes would result in numerous troubling unintended consequences, including significant growth in contraband menthol cigarettes sold through an already widespread underground market”.

In November, California will vote on banning the sale of menthols. If it passes, it will become just the second US state to ban menthols after Massachusetts. The FDA has drafted a national ban that could follow in the next few years, which estimates suggest could save more than 600,000 lives, including almost 250,000 Black lives.

Since last summer, the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and the LA Times have tracked how Reynolds American has been trying to keep menthol cigarettes in the hands of smokers. The company has sought to stoke fears among Black communities about what the bans could mean for them, hiring a team of Black lobbyists, consultants and public figures, including the former congressman Kendrick Meek, and donating to civil rights activist Rev Al Sharpton’s organisation. They have exploited genuine concerns about police brutality and even invoked the murder of George Floyd.

This investigation has uncovered new details about how the individuals and organisations who have aided the company’s objectives have failed to appropriately declare their links to Reynolds American. Protesters were paid to attend a rally organised by a group with close ties to the company.

Seated at the tables in that Atlanta conference room were the very lawmakers the cigarette company has been eager to influence. And Harris was there to convince them. NBCSL’s deputy director Joe Grant said it was incorrect that the audience did not know that Reynolds American was paying for the lunch because “the sponsorship has not changed for 20 years”.

As waiters served pork chops to guests who sipped on sweet iced tea, Harris flicked to the first slide of his presentation. On the two big screens either side of him was an image of Floyd, pinned down on the pavement outside the store he’d just visited, known as the best place in town to buy menthol cigarettes. Derek Chauvin, the police officer who would later be convicted of Floyd’s murder, was kneeling on his neck.

“I chose this picture intentionally because I want to set the tone,” he said.

“I want us to keep in mind not only the murder of this man on the streets of Minneapolis but the unrest that occurred after,” Harris said. “I want to talk to you about how policing intersects with the community and how the decisions that you make as legislators, as citizens, impact how we end up dealing with people on the streets.”

Harris did not mention that, since retiring in 2017, he has become chair of the board of the Law Enforcement Action Partnership (Leap), an organisation that in 2019 received more than a third of its funds from Reynolds American. Leap said that the push toward menthol bans is “the latest iteration of the drug war except that it – more than most laws you see these days – is overtly racist”.

It added: “Smoking is a terrible idea. But if we really believed criminalising cigarettes would get people to quit smoking, then why would we confine the ban to only the tobacco preferences of Black smokers?” When asked about Reynolds’ funding, Leap said that its “message has been the same for two decades, and if someone wants to donate to us to say it, bully for them”. Harris declined to comment further.

At the lunch Harris argued that banning the sale of menthol cigarettes risked driving the market underground, forcing Black smokers to get their fix from illicit sources. The result, he claimed, would be increased policing of Black communities.

Smoking claims 40,000 Black lives each year, but Harris was warning of a different type of cancer in American society – the police brutality that Black communities face every day.

Cooler than cool

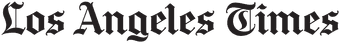

Menthol is deceptive. Suck on a menthol cough drop and you’ll feel your airways open up, a cooling breeze as you breathe in and a momentary easing of the scratchiness in your throat. In reality, it is an illusion – merely the result of a reaction between the menthol and receptors on the surface of your nerves.

A menthol cigarette might taste fresher, even smoother than a regular cigarette. But it features the same harsh tobacco, smoke and tar.

Keith Wailoo remembers the billboard ads that towered overhead in 1970s New York City, a minty-green canopy that pushed the cooling, fresh taste of a menthol cigarette. It was a time when industries noticed an opportunity among a large, concentrated and newly urbanised Black population.

“Advertisements were everywhere,” said Wailoo. “You had sidewalk billboards, you had street corner billboards, you had billboards on the side of buildings, you had billboards at the top of buildings.”

As tobacco companies looked for new markets, advertising campaigns targeted Black communities

Rita Harper for TBIJ

As tobacco companies looked for new markets, advertising campaigns targeted Black communities

Rita Harper for TBIJ

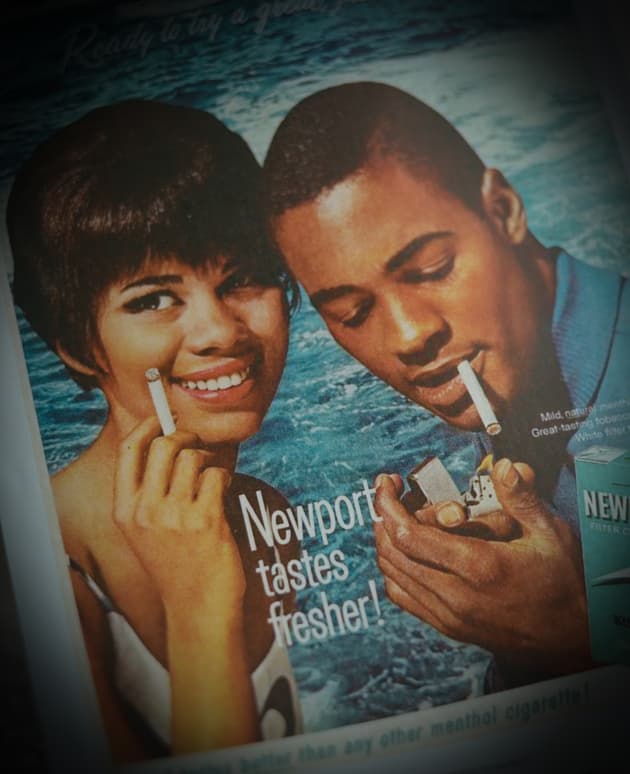

Menthol brands like Kool and Newports quickly became the cigarettes of choice for Black smokers

Rita Harper for TBIJ

Menthol brands like Kool and Newports quickly became the cigarettes of choice for Black smokers

Rita Harper for TBIJ

Tobacco companies repackaged an old product as a new, cool cigarette and pitched it at the Black communities in America’s rapidly changing cities.

“I grew up reading Black publications like Ebony and Jet and menthol was all over it,” said Wailoo, now a history professor at Princeton University and author of a book about menthol cigarettes called Pushing Cool. Looking back, he now realises he grew up at the “high point of the racialisation of menthol smoking”.

Despite being invented almost half a century earlier, it was not until around the time of Wailoo’s early years in New York that the idea had begun to take hold in the industry that there might be a market for menthol cigarettes among Black smokers.

With the rising smoking rates of the 1920s came more and more cases of so-called smokers’ throat, irritation caused by too much smoking. Menthols were pitched to the health conscious as a salve. The cooling, slightly anaesthetic quality of menthol was a break from the harshness of your regular cigarette.

But a report from the US surgeon general in 1964 sparked fresh concerns about the health effects of smoking and created new skepticism about how the industry was targeting young people. It pushed cigarette makers to find new markets. That same year, Brown & Williamson began to use Black publications to promote their Kool brand of menthol cigarettes.

The campaign was a success and triggered other companies to emulate the Kool strategy.

In the years that followed, the tobacco industry committed huge amounts of time, energy and resources to understanding race and society, all for the purposes of selling cigarettes. At times, they came to conclusions based on old racist tropes, such as one 1970s marketing memo which suggested that Black people prefer menthols because they were “said to be possessed by an almost genetic body odor”. But the companies also broke new ground.

“The industry was doing Black studies, and even masculinity studies and gender studies well before these existed as areas of academic study,” Wailoo said. “They were trying to understand everything possible about how you create markets and how you influence behaviour. And they understood that they needed to study Black culture and Black society.”

Miya Bailey remembers being sent as a young child to buy packs of More menthol cigarettes for his grandmother. She later died of emphysema, a lung condition usually caused by smoking

Rita Harper for TBIJ

Miya Bailey remembers being sent as a young child to buy packs of More menthol cigarettes for his grandmother. She later died of emphysema, a lung condition usually caused by smoking

Rita Harper for TBIJ

The result was a level of finely tuned marketing that few had tried before.

For instance, a study from Detroit in the 1970s commissioned by RJ Reynolds (which became a subsidiary of Reynolds American when the company merged with BAT in 2004) looked into how the company should advertise on buses. While “bus ridership is predominantly Black,” the study’s authors wrote, they realised that “in many cases routes pass through all Black neighborhoods as well as surburban White.” Tobacco companies were struggling to tap into the new market of Black consumers while also not alienating their white clientele. But the fear was that any gains made among Black smokers from targeted advertising could be outweighed by losses among whites.

The authors concluded that the buses’ “exterior advertising should be compatible to both market segments” but that “interior advertising should specifically address this [Black] group”. Targeting like this, as well as sponsoring events and handing out free menthols, often to kids, was hugely effective.

A multi-billion dollar settlement in 1998 between state attorneys general and the then four largest cigarette makers in the US severely curbed how the industry could advertise. While the billboards that Wailoo remembers are gone, the demand for menthol cigarettes among Black smokers persists.

Paid protestors

For three long, hot hours on the morning of June 15, 2021, the protesters stood outside LA City Hall wielding signs carrying messages such as “No ban on menthol” and “Whites can smoke. Blacks cannot.”

On the back of their matching white T-shirts was the logo of the organisation who had arranged the rally, Neighborhood Forward, a new, relatively unknown group led by a local pastor.

Describing itself on Twitter as “a collective of real voices from Black and Brown communities working together to bring about real change,” the group emerged in the wake of Floyd’s murder in 2020 and has since taken aim at California’s plan to ban flavoured tobacco, which includes menthol. The bill, known as SB 793, was signed into law in August 2020, but a petition signed by more than 600,000 voters pushed it to a referendum, which is due in November. To date, RJ Reynolds and Philip Morris USA have pumped more than $20m into the campaign to block the bill.

“To any and everyone that has done a rally with us before, in order to grow our number of participants, I am asking that you make a list of your trusted family, friends, neighbors, and church members who would be interested in doing this type of work,” read a text message sent to attendees ahead of the rally and seen by the Bureau. “Menthol T-shirts will be provided… The pay is $80 for 2½ - 3 hours.”

Pastor KW Tulloss, Neighborhood Forward’s public face, is a former leader of the local chapter of the prominent civil rights group National Action Network, which was founded by Al Sharpton and has been funded by Reynolds American. He was happy to speak about the work the group was doing fighting SB 793, but when asked where Neighborhood Forward got its money, he said, “We can't focus on those sidebar conversations” and that we should “check public records”.

Yet there is little public information about Neighborhood Forward. While the LA-based Tulloss is often described as the group’s co-founder, business filings lead 1,500 miles east, to Missouri. There, the group was incorporated by Charles Hatfield, a lawyer specialising in government relations litigation. Asked to explain how his role with Neighborhood Forward, seemingly a small grassroots movement, fitted with this work, Hatfield said: “I don’t feel any obligation to help you with that.”

Even the person listed as the chair of Neighborhood Forward’s board, the Missouri-based lobbyist Leroy Grant, declined to answer basic questions about the organisation and his interest in menthol cigarettes. “I’m not really able to speak on that issue,” he said, before hanging up the phone.

While public records do not show how the group is funded, they do reveal that one of its directors is the California-based lobbyist Ingrid Hutt. She worked for Reynolds American for several months in 2019, hired to “promote the unintended consequences of the menthol ban in the African-American communities in the City of Los Angeles”, according to lobbying disclosures. She did not respond to multiple attempts to reach her.

Another director is Corey Pegues, who was once part of a Reynolds American-funded group called the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives (Noble). Tulloss said that Noble, which has campaigned across the country against menthol bans, first brought the issue to his attention.

Reynolds American did not comment on these points.

“These Black leaders act as if menthol cigarettes just drop from the sky and are not the result of decades of racist, pernicious targeting. They allow these white tobacco industry executives to cynically exploit our legitimate grievances,” said Carol McGruder, a co-founder of the African American Tobacco Control Leadership Council (AATCLC). In her view, “the time of this being acceptable is long past”.

Thriving off the addictions of the oppressed

In the US, health outcomes are worse for Black people. Life expectancy at birth is lower than for Hispanic or white people. Black people in the US have the highest death rate and lowest survival rate of any racial or ethnic group for most cancers.

Although Black people smoke at similar rates to white people, proportionally more Black people die of smoking-related diseases. One study estimated that menthol cigarettes have helped recruit 10 million extra US smokers since 1980. Not only can menthols be “good starter products” (as the industry once put it), some research suggests that they may be harder to give up. This could explain why Black smokers try to quit more than white smokers, but they are less likely to succeed.

Agde, a food mart owner in New Orleans, says Kool menthol cigarettes are the best-selling brand at his store

Rita Harper for TBIJ

Agde, a food mart owner in New Orleans, says Kool menthol cigarettes are the best-selling brand at his store

Rita Harper for TBIJ

The success of big tobacco in creating a sustained market for menthols among Black smokers is hard to deny. One industry survey in the 1950s found that only 5% of Black smokers chose Kool, one of the only menthol brands on the market at the time, compared to 2% of white smokers. Today, that 3% gap has grown into a chasm – 85% of Black smokers now choose menthols, compared to just 30% of white smokers.

In general, Newport cigarettes are cheaper in neighbourhoods with higher proportions of Black residents, young people and lower income households. Because the industry had created the demand, store owners in those areas sought contracts with manufacturers of the most popular menthol brands, such as Reynolds American. In return, the stores can offer cheaper prices. Despite the 1998 lawsuit restricting how tobacco can be advertised, the ripples of this racist past can still be felt more than two decades later.

“There was some type of [unspoken] acknowledgement that if we can keep it addictive in this neighbourhood then we're going to exploit it the best way we possibly can,” claimed a former salesperson for RJ Reynolds who worked in a predominantly Black neighbourhood until 2013 and asked to remain anonymous. In their opinion, “the health of Black and Brown people has never been looked at in a positive way from industries like RJ Reynolds and other tobacco companies… They thrive off the addictions of the oppressed.”

Groups dedicated to reducing these health inequalities have spent years campaigning for menthols to be banned. They stress the fact that such policies stop the sale of menthol cigarettes rather than criminalising their use. This should, they say, mitigate any concerns about how the bans could lead to greater policing of Black communities.

“We need to be able to walk and chew gum at the same time,” said McGruder, the tobacco control campaigner. Since 2008, her group AATCLC has campaigned for menthol cigarettes to be taken off the market. “We need to deal with both these issues at the same time.”

A year after AATCLC was founded, then-President Barack Obama signed into law a ban on flavoured cigarettes – except menthol. Some members of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC), a group of Black US lawmakers in Washington, DC that over the years has received hundred of thousands of dollars from the tobacco industry, were seen as key in securing the exemption for menthol at the time.

Since then, the industry has grown ever more reliant on revenues from menthols. In 2020 (the most recent data available), they made up more than a third of total cigarette sales, the highest proportion ever. LaTrisha Vetaw, who campaigned for banning their sale in Minneapolis, described menthols as the industry’s “cash cow”.

“They are always talking about social justice, why aren't they challenging the industry?” Vetaw asked. “Their board rooms are full of white men in suits.”

Today, the CBC’s membership, alongside the likes of the NAACP, have come out in support of a nationwide ban on the sale of menthol cigarettes. The FDA has said it is committed to banning menthol as a characterising flavour in cigarettes, which could wipe the 30 billion Newport menthol cigarettes Reynolds American sells every year to zero.

Positions of power

Denice Edwards sat on the back row of the council chambers on the fourth floor of Denver City Hall. She was wearing all black but her shock of amber hair stood out, even among the crowd of campaigners wearing loud T-shirts with slogans sprawled across their chests.

Just two weeks before the conference in Atlanta, Denver’s Safety, Housing and Homelessness committee was debating a bill that would ban the sale of flavoured tobacco, including menthol cigarettes.

The bill proved divisive. The debates drew more people to City Hall than any other time since the start of the pandemic. The committee was the first hurdle for getting a bill passed into law in Denver. Unusually, the bill was being discussed by the committee for the third time.

Unlike many of those in the audience on that brisk November morning in Colorado’s capital, Edwards was not there to speak. Her work had already been done. She told a reporter from the Bureau that she’d spoken to a number of the council members ahead of the meeting. She was simply “monitoring the issue”.

Kevin Flynn, a council member who sits on the committee, had proposed an amendment to the bill that would mean menthol cigarettes would be exempted from the ban. He would rather see stricter enforcement and bigger penalties for retailers who illegally sell cigarettes to minors than an outright ban on menthols.

“[It felt] very uncomfortable for me, as a white man, to be asked to tell my Black constituents, ‘You can’t buy this anymore’,” Flynn told the Bureau. “The tobacco industry has marketed just like any industry markets to its target market, right? It’s not specific or peculiar to menthol cigarettes in the Black community, but any tobacco products to any community. I wish they wouldn’t do it at all but I’m not going to single out Black consumers.”

Flynn said he “met with anybody who wanted to meet with me”. He told the committee he had heard conflicting opinions from those in the Black community, including from Edwards, whom he’s known for decades and who is staunchly opposed to banning menthol cigarettes.

“She just called me up and asked for a meeting,” Flynn said. “It was before the bill was even introduced… Denice was actually the first person who approached me about it. I guess she knew this was in the works.”

But Edwards is not just an old acquaintance. She’s a lobbyist hired by Reynolds American – one of at least three consultants working for the company on this issue in Denver. Although Flynn told the Bureau he was aware of her ties to a tobacco company, she did not disclose them on the city’s lobbying register, and questions arise about whether she might have broken registration rules by speaking with council members. Edwards did not respond to a request for comment.

Her involvement in Denver also shows how Reynolds American consultants have been key in furthering the company’s interests in levels of government it has rarely lobbied before.

Flynn and Edwards first met when he was a reporter at the local newspaper and she was working for the city’s first Black mayor, Wellington Webb. Nearly two decades since he held office, Webb remains a huge figure in Denver, not least for his six foot four inch frame. During the 1991 mayoral race, he began as a practically unknown candidate. But his energetic campaign, during which he walked door-to-door speaking directly to voters, secured him a landslide victory. It became known as the “sneaker campaign”. Shoes he wore at the time – a tattered pair of blue Asics – are now on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC.

Reynolds American sells 30 billion Newport menthol cigarettes every year

Rita Harper for TBIJ

Reynolds American sells 30 billion Newport menthol cigarettes every year

Rita Harper for TBIJ

In early October, not long before Flynn introduced his amendment, Webb wrote an opinion piece for the local newspaper, The Denver Post. He mentioned Eric Garner, the Black man choked to death by New York police officers in 2014 after being accused of illegally selling cigarettes.

“Law enforcement hardly needs more reason to stop us from going about our lives. But that's what a menthol ban could do,” Webb wrote. (When asked about the menthol ban, Edwards said: “I’m on the side of Mayor Webb.”)

But a few weeks later, Webb’s opinion piece was removed from the newspaper’s website. A correction in print noted that he had not told the editors he was working as a consultant for Reynolds American, a fact uncovered by one of the newspaper’s journalists. It is another example of how the company has been able to curry influence, often undetected.

Calling on communities

Denver is not the only US city to have considered banning the sale of menthol cigarettes. To date, around 150 localities across the country have placed some sort of restriction on their sale, most issuing an outright ban.

Reynolds American has called upon politicians both local and national, such as Webb and former US Senator Meek. But its focus has not only been in the corridors of power. Through pastors such as Sharpton and Tulloss, the company has sought to tap into a long history that has put the church at the centre of many Black communities.

“Even going back to the period of enslavement, often [Black] preachers were looked to be the spokespersons” for the Black community, said Obery Hendricks, a scholar at Columbia University who has studied the intersection of religion and political economy. “The pastors play a major role in representing the interests of Black churches and they play a major role in building educational institutions and supporting protest.”

“The tobacco industry knows the hold that Black pastors have over Black churches,” he adds. “It's a sad commentary because the tobacco industry would not think it strategically useful to approach the Black church if they didn't know that Black pastors would be amenable to working with them.”

The tobacco industry has long called on the support of Black individuals and organisations. While it was building its brands in those communities through the latter half of the 20th Century, it also built a web of allies, stretching from prominent civil rights groups and politicians to musicians and artists. It is just one way that they “undergird their position within the Black community,” said Hendricks.

Despite the industry cultivating these relationships for many decades, there is still a desperate lack of Black representation across both executive-level and board-level positions at all the major tobacco companies. In fact, in comparison to those who have lobbied for Reynolds American against banning menthol cigarettes, almost the entirety of the company’s senior management team is white.

“The web that keeps menthol present in cities is not an accident. It’s not driven by some kind of innate Black taste for menthol,” said Wailoo. “It is a byproduct of a complex and relentless story of how markets were built and sustained.”

These markets do not just appeal to Black adults. More than half of kids between the ages of 12 and 17 who smoke use menthol cigarettes. Almost all African-Americans who smoke started with menthols.

Council members like Denver’s Amanda Sawyer, who co-sponsored the bill that would ban the sale of flavoured tobacco in her city, are worried about young people of all races using menthols as a gateway to a life of smoking.

In her office, a few doors down the corridor from the committee room in Denver City Hall, Sawyer had been doing the maths. In purple marker on a whiteboard were the numbers one to 13. A series of crosses and dashes next to each one indicated how she thought the 13 members of the city council might vote on the bill and its amendments. By her estimation, she had the numbers.

Indeed, as Sawyer predicted, Denver’s city council voted in favour of banning almost all types of flavoured tobacco, including menthol cigarettes, in December. Despite Edwards’ best efforts, the amendment to exempt menthol had failed. All that was left was for the city’s mayor Michael Hancock to sign the bill into law.

But another Reynolds American consultant, Art Way, who had previously spoken with the mayor’s staff about the proposed ban, wrote to Hancock’s office imploring him to veto the bill, according to emails released in response to a public records request by the Bureau.

“Unfortunately, it is the very communities the ban is supposed to protect that will engage in grey market activity increasing the spectrum of criminality for both youth and adults of color,” wrote Way. Nowhere in his email did Way explain his ties to Reynolds American. And, like Edwards, he is not on the city’s lobbying register. Way said he had believed his Colorado state lobbyist registration was adequate.

Way told the Bureau that his email, one of dozens sent to the mayor’s office on this issue, “was likely no more beneficial than others”. He added: “In order to water down my message, flavour ban proponents would like me to shout from the rooftop regarding my client. I’ve disappointed in this regard on occasion but never purposefully tried to hide my affiliation.”

In his 11-year tenure Mayor Hancock had vetoed just one bill.

The day after Way’s email arrived, the mayor wrote a letter to the council members. The “well-intentioned” bill banning menthol cigarettes had become the second.

Header image: Protestors in white T-shirts with the slogan "Say No to SB 793" walk past a No Smoking sign. One of the protestors carries a sign that says "SB 793 is a racist law". Image credit: ZUMA Press Inc/Alamy Live News

Reporters: Ben Stockton, Emily Baumgaertner and Ryan Lindsay

Impact producer: Paul Eccles

Health editor: Chrissie Giles

Global editor: James Ball

Editor: Meirion Jones

Fact checker: Alice Milliken

Production: Frankie Goodway

Legal team: Stephen Shotnes (Simons Muirhead Burton)

Original photography: Rita Harper

Our reporting on tobacco is part of our Global Health project, which has a number of funders. The Big Tobacco project is funded by Vital Strategies. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.