Swiss tech company boss accused of selling mobile network access for spying

Mitto AG’s network used to track people via mobile phones, former employees say

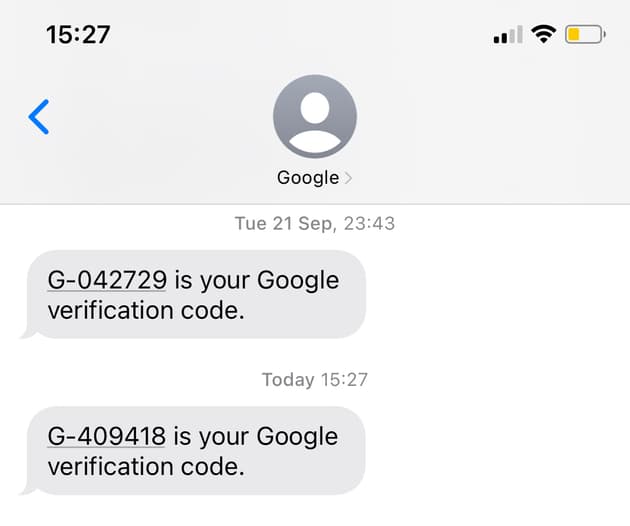

The co-founder of a company trusted by Google and Twitter to text security codes to millions of users also ran a service that helped governments secretly surveil and track mobile phones, according to former employees and clients.

Since it started in 2013, Mitto AG has established itself as a provider of automated text messages for such things as sales promotions, security codes and appointment reminders. Mitto, a privately held company with headquarters in Zug, Switzerland, has grown its business by establishing relationships with telecom operators in more than 100 countries.

It has brokered deals that gave it the ability to deliver text messages to billions of phones in most corners of the world, including countries that are otherwise difficult for Western companies to penetrate such as Iran and Afghanistan. It has attracted major technology giants as customers, including Google, Twitter, WhatsApp, Microsoft’s LinkedIn and messaging app Telegram, in addition to China’s TikTok, Tencent and Alibaba, according to Mitto documents and former employees.

But an investigation by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, carried out in collaboration with Bloomberg News, indicated that the company’s co-founder and chief operating officer, Ilja Gorelik, was also providing another service: selling access to Mitto’s networks to secretly locate people via their mobile phones.

That Mitto’s networks were also being used for surveillance work was not shared with the company’s technology clients, or the mobile networks Mitto works with to spread its text messages and other communications, according to former Mitto employees. The existence of the alternate service was only known to a small number of people within the company, these former employees said. Gorelik sold the service to surveillance companies which in turn contracted with government agencies, according to the employees.

Mitto sends security messages like these on behalf of tech giants

TBIJ

Mitto sends security messages like these on behalf of tech giants

TBIJ

Responding to the Bureau's questions, Mitto issued a statement saying that the company had no involvement in a surveillance business and had launched an internal investigation “to determine if our technology and business has been compromised.” Mitto would “take corrective action if necessary,” it wrote.

“We are shocked by the assertions against Ilja Gorelik and our company,” Mitto wrote. “To be clear, Mitto does not, has not, and will not organise and operate a separate business, division, or entity that provides surveillance companies access to telecom infrastructure to secretly locate people via their mobile phones, or other illegal acts. Mitto also does not condone, support, and enable the exploitation of telecom networks with whom the company partners to deliver service to its global customers.”

Gorelik did not respond to requests for comment. A Mitto representative declined to comment on Gorelik’s current role with the company.

Two sources who said their former company worked with Gorelik to carry out surveillance for governments added that he installed custom software at Mitto that could be used to target certain people. They claimed that, during the work, there was virtually no oversight of surveillance carried out using Mitto’s systems, creating potential opportunities for misuse.

In at least one instance, a phone number associated with a senior US State Department official was targeted in 2019 for surveillance through third party use of Mitto’s systems, according to documents reviewed by the Bureau and a cybersecurity analyst familiar with the incident, who requested anonymity because of a confidentiality agreement. It is not clear who was behind efforts to target the official, who was not identified by the documents or the analyst.

Marietje Schaake, international policy director at Stanford University’s Cyber Policy Center, said the revelations were “troubling” and highlighted a “huge problem.”

“The biggest technology companies that provide critical services are blindly trusting players in this ecosystem who cannot be trusted,” Schaake said, after being told about the Bureau and Bloomberg’s reporting. “It’s dangerous for human rights. It’s dangerous for trust in an information society. And it’s dangerous for trust in companies.”

US senator Ron Wyden, a Democrat from Oregon and a member of the Senate intelligence committee, said in a statement that he had previously raised the alarm about security vulnerabilities in US phone networks, which he feared could be exploited to spy on government officials. “I’m very concerned that the federal government has done nothing to protect federal employees from this sophisticated surveillance threat,” Wyden said.

Mitto’s partner networks have included Vodafone, Telefónica, MTN and Deutsche Telekom, according to company documents reviewed by the Bureau. Vodafone said that its enterprise division has worked with Mitto in two countries to provide text messaging services. A Telefónica representative said he was not immediately able to confirm whether the company had a relationship with Mitto but said he was looking into the matter. MTN and Deutsche Telekom did not respond to requests for comment.

There is no indication that the surveillance operation compromised any data of the tech companies that rely on Mitto to send messages. Representatives from Twitter and WhatsApp declined to comment. A spokesperson for LinkedIn, which Mitto has featured on a list of apparent clients on its website, said the company does not work with Mitto and declined to say whether it had in the past.

Alibaba said it couldn't immediately confirm any relationship with Mitto. Representatives from Google, Telegram, TikTok and Tencent did not respond to requests for comment.

The investigation by the Bureau and Bloomberg News is based on interviews with more than two dozen people, including former Mitto employees, surveillance industry insiders, cybersecurity professionals, as well as emails and documents describing the surveillance work. Nearly all of the former employees requested anonymity because they had signed confidentiality agreements or were concerned about the possible consequences of speaking out. Of the former employees interviewed for this story, only a handful said they knew specific details about the surveillance work.

The revelations offer another example of security weaknesses in global telecommunication systems that some governments and private contractors have been accused of exploiting to spy on people. There has been a boom in technology tools that let governments hack, track and otherwise monitor people’s phones and communications, and the market for mobile phone surveillance technology has been valued as high as $12 billion. But despite the sector’s size, companies offering the tools often operate beyond public scrutiny and are subject to little regulation.

Many of the surveillance companies, such as Israel’s NSO Group, and their government clients maintain that the technology is used to catch criminals and terrorists. But in recent years there have been numerous instances when governments have used surveillance technology to spy on dissidents, journalists or others, according to reports by media organisations and digital rights groups.

“The private sector surveillance industry is growing fast, but it’s operating in the dark, without any accountability or transparency, and there have been real human rights implications because of that,” said Jonathon Penney, a research fellow at Citizen Lab, an interdisciplinary team at the University of Toronto that has repeatedly exposed alleged misuse of surveillance technology.

Mitto was co-founded in 2013 by Gorelik and Andrea Giacomini, European entrepreneurs who were bound by their interest in telecommunications. While its headquarters are in Switzerland, most of its roughly 250 staff have been based in Germany and more recently, Serbia, according to former employees.

Gorelik began his career as an IT specialist working for IBM, before becoming a technology entrepreneur and investor, helping to create a dating app named Lovoo, according to business records.

At Mitto, he assisted in building the company’s technical infrastructure. Aspects of his behaviour and management style raised concerns, according to former employees, who allege he sent emails under a pseudonym and installed spyware on their computers.

Mitto leased hundreds of “global titles” from telecom companies – unique addresses that are used to route messages, giving the company the ability to send text messages in bulk to people internationally.

In Mitto’s early days, the company’s primary business was providing marketing and advertising services. Businesses would pay Mitto to send out millions of text messages, promoting products or events, according to former Mitto employees. By 2017, Mitto had set up direct connections to mobile phone networks in more than 100 countries, and established partnerships with leading telecommunications companies.

Between 2017 and 2018, Gorelik started giving surveillance companies access to Mitto’s networks, which were then used to locate and track people via their mobile phones, according to four former employees.

The alleged venture involved exploiting weaknesses in a telecom protocol known as SS7, or Signalling System 7, a sort of switchboard for the global telecoms industry. First developed in the 1970s, SS7 contains numerous known vulnerabilities that governments and private surveillance companies have in the past exploited to spy on phones.

A US Department of Homeland Security report in 2017 noted that security holes in SS7 made it possible for an adversary to determine the physical location of mobile devices and intercept or redirect text messages and voice conversations.

While there are newer telecom protocols available, mobile network operators continue to use SS7-based technologies despite security concerns, in part because they are costly and complex to replace, according to Tobias Engel, a researcher who specialises in mobile phone network security. Mobile phone network operators can use firewalls to identify and block surveillance attempts that exploit SS7 security weaknesses, but those systems need to be regularly updated and tested to be effective, he said.

Mitto’s deals with telecommunications companies, according to former employees, provided the company with SS7 access, which Mitto could use to route text messages in bulk across the world’s mobile networks.

But in that process, “there’s a lack of audit and a lack of accountability” that opens up the possibility for SS7 access to be exploited for surveillance purposes, according to Pat Walshe, a privacy expert with more than two decades of experience in the telecommunications industry.

The four former Mitto employees familiar with Gorelik’s alleged activities claimed he provided surveillance services to multiple companies. Gorelik also told some colleagues that he had connections to a national spy agency in the Middle East and was helping that country’s defence ministry track people’s locations, according to the former employees. The Bureau is not naming the country at the behest of a Mitto representative for security reasons.

Four former employees of Cyprus-based firm TRG Research and Development said Mitto’s network was used by their company to provide surveillance services to customers from 2019 to 2021. The employees requested anonymity owing to confidentiality agreements.

Make change possible

Investigative journalism is vital for democracy. Help us to expose injustice and spark change

Click here to support usTRG provides a software platform to governments and law enforcement agencies that they can use to track mobile phones and gather intelligence from social media websites. TRG says its mission is to “help our customers in the fight against crime and terror,” providing them with “conclusions based on our data collection and data fusion engines.”

Two of the former TRG employees said staff at the company had worked directly with Gorelik, using Mitto’s access to global mobile phone networks to obtain location data on targeted mobile phones and in some cases call logs showing who particular people were contacting and when. The other two said they knew TRG had used Mitto’s network but did not confirm whether Gorelik had any personal involvement.

A TRG spokesperson denied the allegations and said the company has never had a “commercial relationship” with Mitto and had not worked with Gorelik. “If anyone within TRG or Mitto has had such relationships, it is a personal relationship and is not related to TRG,” the spokesperson said. A Mitto representative declined to comment on the company’s alleged relationship with TRG.

TRG confirmed it sold a system named “Intellectus,” which uses third-party applications to provide information requested by government agencies. The spokesperson said the company “does not employ or collaborate with hackers/hijackers” and does not have spying or signalling abilities.

However, recent publicly posted job advertisements for roles at TRG have sought people with expertise in telecommunications signalling protocols such as SS7, as well as knowledge of “lawful interception,” an industry term understood to mean surveillance of communications. Images on TRG’s website show the “Intellectus” system can be used to track people’s locations, monitor their call and text message records and identify their connections on Facebook.

The TRG spokesperson said Intellectus is operated solely by customers, who must sign an end user statement agreeing that the technology is used in accordance with their national laws and that there is no abuse of the system. “TRG has an internal legal and compliance department which conducts thorough due-diligence checks for each and every end user,” the spokesperson said. “Automated algorithms in Intellectus may detect any misuse in regards to usage of the system, which subsequently blocks access of the respective user(s).”

The Bureau newsletter

Subscribe to the Bureau newsletter, and hear when our next story breaks.

The four former TRG employees said that their work with Mitto’s network was carried out by them in their capacity as TRG employees and that some senior executives knew about it.

Gorelik had personally installed custom TRG software within Mitto’s computer networks, two of the former TRG employees alleged. They claimed TRG’s software had established what is called a “signalling connection” between Mitto and specific mobile network operators. Such connections are intended to be used for legitimate purposes including routing calls or messages to phones.

However, TRG’s software could be used to spy on targeted phones for government customers, and could send requests to mobile phone networks that could trick them into sending back a trove of data, according to the former TRG employees.

The full roster of customers for the surveillance business isn’t known, and the Bureau and Bloomberg were not able to verify several companies that were identified as purchasing the service.

Other surveillance firms have sold capabilities that exploit vulnerabilities in SS7 protocols to government customers, including the Israeli firm Rayzone and Bulgaria-based Circles, according to previous reports from the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and Citizen Lab.

Gorelik’s association with the surveillance industry was a closely guarded secret within Mitto, according to former employees. But one cybersecurity professional working in the telecommunications industry had suspicions.

One particular incident stood out from November 2019. A sudden flurry of signalling messages, which are commonly used to request location information about a particular phone, were targeted at a senior US State Department official, according to records of telecommunication network activity seen by the Bureau and a cybersecurity analyst who reviewed them. The analyst spoke on condition of anonymity because of a confidentiality agreement. Neither the analyst nor the records provided the official’s name.

At least 50 of the signalling messages were sent to a US phone network used by the official at a rate of one or more every second, seeking information about the person’s mobile phone and its location, the records show. The signalling messages were traced back to 15 different countries, where they had been sent through a series of unique addresses – or global titles – that were all leased by Mitto, according to the records.

On another occasion, in July 2020, Mitto’s network was linked to attempted surveillance of an unidentified person located in South East Asia, according to the analyst. Global titles used by the company in Russia, Zambia, Madagascar and Denmark sent out a coordinated burst of signalling messages targeting the person’s phone, the records show. The messages included a command that can be deployed to surreptitiously access text messages, according to the cybersecurity analyst.

The analyst said the attempts targeting the State Department official and the person in South East Asia were flagged as malicious by security systems and blocked. Mitto’s system was detected engaging in similar activity on dozens of other occasions, according to the analyst and the records.

The data, the analyst said, made it clear that Mitto's infrastructure had been used by third parties to enable signalling attacks globally.

Got a Story?

We welcome tip-offs from the public and we always protect our sources

Find out how to work with usGorelik’s alleged surveillance work at Mitto caused some discomfort. The company, which bills itself as the industry’s “most trusted” provider of text message services, says it offers those services “free of any potential threats and risks”.

Three of the former employees at Mitto said they quit in part because they felt the work claimed to have been carried out by Gorelik in the surveillance sector had posed a conflict, undermining the company’s ability to guarantee the privacy and security of messages it processed.

Gorelik’s behaviour had raised other concerns too, the former employees said.

For more than a year, ending at the start of 2017, Gorelik was rarely in the company’s offices and sent emails and messages under the name “Ingo Gross,” according to seven former employees. The former employees claimed Mitto managers told them that Gorelik couldn’t use his real name for legal reasons that were never explained.

Shortly after that, they alleged that Gorelik began to spy on some colleagues, using the company’s access to telecommunication networks sometimes to check his employees’ locations, according to six former employees. Gorelik was also known sometimes to question employees’ use of their work computers for non-business purposes.

It later became clear how he knew what websites they were visiting. In the summer of 2019, a group of developers at Mitto’s office in Berlin discovered that Gorelik had installed a spy tool on work computers, which would take a screenshot every two minutes. The Bureau and Bloomberg reviewed images showing the spy tool in operation. It is illegal for companies to install spyware on employee computers in Germany unless there is solid evidence of criminal behaviour or serious breach of duty, according to Henriette Picot, a Munich-based commercial technology lawyer.

Mitto said in a statement that it “uses customary and legal techniques” to monitor such things as who is accessing its computer network and internet activity on a random basis or based on concrete suspicions.

“None of our employees has ever brought to our attention that they feared illegal spyware was being used on their company-provided workstations,” the company wrote.

Some of the employees confronted Gorelik, who is said to have explained in a staff meeting that he had deployed the spy tool owing to concerns about employees leaking proprietary information, the former employees said.

Mitto later scaled down its presence in Germany and relocated to Belgrade, Serbia, according to Stefan Link, a former senior customer support engineer. He said he did not know about the alleged surveillance service.

Link, who worked in Berlin for the company, said that his own job was outsourced to Serbia and his contract not renewed when it expired in mid-2018. He felt that “it was leadership based on fear”, citing the alleged spying on employees and Gorelik’s occasional berating of employees. “And you didn’t know who you could trust.”

Header image: A man uses his phone to access an account on his laptop with two-step verification. Credit: Sergey Shulgin/Getty Images

Reporters: Crofton Black and Ryan Gallagher

Global editor: James Ball

Editor: Meirion Jones

Production editor: Frankie Goodway, Alex Hess and Emily Goddard

Fact checker: Alice Milliken

Legal team: Stephen Shotnes (Simons Muirhead Burton)

Our reporting on Decision Machines is funded by Open Society Foundations. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau's editorial decisions or output.

-

Area:

-

Subject: