‘Impossible to enforce’: Big Tobacco exploiting loopholes in European menthol ban

Tobacco companies are finding loopholes in the Europe-wide menthol cigarette ban in order to keep selling products that can get new, younger smokers hooked on tobacco.

Japan Tobacco International (JTI) – which owns Sterling, Benson & Hedges and Sovereign – has been able to work around a ban imposed in 2020 that was intended to prevent young people from taking up smoking cigarettes. Competitors have called for governments to investigate the company’s new “menthol reimagined” products.

A joint investigation by the Bureau and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) can reveal new details of how confusion across Europe means that, almost 18 months after the ban came into force in the EU and UK, nobody knows for sure whether certain types of cigarette are covered by the ban. A breach of the ban could potentially be a criminal offence. Previously unreported documents show the tobacco industry attempting to press public health authorities as well as mudslinging between cigarette makers accusing each other of undermining the ban.

Once described by the industry as “good starter products”, menthol cigarettes have a minty taste that is less harsh and easier to inhale, making them appeal to many younger smokers.

“The industry is circumventing the menthol ban for fear that otherwise menthol smokers may quit, and so it can continue to provide products it knows are easier for new young smokers to inhale,” said Deborah Arnott, chief executive of the health charity Action on Smoking and Health.

The UK and EU banned cigarettes with a “characterising menthol flavour” in May 2020. But this category, Arnott said, is “hard to measure and difficult, if not impossible, to enforce”.

JTI said: “We are confident that all JTI products are fully compliant with the law and do not have characterizing flavors.”

The sniff test

Before the ban, one in five UK smokers bought menthols. In the months before the law came into force, the industry launched a number of alternative products.

JTI, which is the world’s third largest tobacco multinational, rebranded some of its menthol cigarettes under its “New Dual” range. Its claim that these cigarettes contained a new blend of tobacco with lower levels of menthol triggered a slew of investigations across Europe.

Meet the new box: JTI's rebranded menthol cigarettes

Meet the new box: JTI's rebranded menthol cigarettes

Most of these inquiries have been thwarted by EU rules that prevent multiple member states from investigating the same products at the same time. The first was launched by the Swedish government and, to ensure consistency across the bloc, the EU requires other governments to wait until that investigation is completed before taking any action of their own.

Responding to queries from public health agencies across Europe about the cigarettes, JTI said that continuing to investigate the products would be in breach of these rules. In the meantime, it has repeatedly stated that it “firmly believes” the blend does not constitute a “characterising flavour”, the term used in the EU ban.

However, in an email to UK Trading Standards last year seen by the Bureau, the company admitted that there was, in fact, no way of knowing. “There is no mandatory or official testing method that JTI can use to determine whether finished products containing our new blend have a ‘characterising’ flavour or not,” it said.

The term that has led to this confusion was itself proposed by the tobacco industry. A 2007 internal document from the maker of Marlboro cigarettes, Philip Morris International, sets out how the company could respond to the tightening grip of regulation. It suggests the company itself could “propose a ban on ‘characterizing flavours’,” although it added that menthol should be exempt.

Although EU member states agreed the ban in 2016, it took nearly five years for a group of experts to put in place a methodology for assessing flavour approved by the European Commission. It was established in March, some 10 months after the menthol ban came into force.

The solution? A combination of chemical analysis and sniffing.

To join the “sensory panel”, applicants had to make it through a rigorous selection process, including a smell test and assessment by a behavioural psychologist. The 34 people selected were then put through a 15-day bootcamp to train them to sniff out menthol cigarettes.

A leaked document seen by the Bureau and OCCRP reveals the Swedish government referred 21 varieties of cigarette owned by JTI to the commission for testing in June 2020. Progress has been slow, partly because it is the first time this procedure has been used, and the testing is ongoing. The EU told the Bureau it would "take further action" against the tobacco companies if they were breaking the menthol ban.

Also in June last year, the UK government announced that Public Health England (PHE) was investigating cigarettes from JTI and possibly other manufacturers for potentially contravening the ban. But EU rules prevented the agency from launching its own testing until the commission’s investigation had concluded or the UK had left the bloc on 31 December.

In September 2021 a PHE spokesperson told the Bureau that testing of “products from a range of manufacturers” including JTI will begin in October and conclude by the end of the year. This will be more than 18 months since the ban came into force. (The investigation has since been taken over by the new Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, after PHE was axed on 1 October.)

In this regulatory vacuum, JTI has been free to market its new “menthol reimagined” cigarettes across Europe. In the UK alone, sales of these brands are estimated to have topped £1bn in the year following the ban, according to market data reported by the Daily Mail.

JTI’s competitors have become increasingly frustrated with what they see as a lack of action by PHE. Their anger seems to stem from concerns about the threat to their profits and “the ongoing growth in the vaping sector”.

Initially, British American Tobacco (BAT) said JTI’s new product line “damages attempts by BAT to actively participate in reducing the health impact of our industry”. Later, however, it threatened to launch its own brand of cigarettes to compete with JTI if nothing was done.

BAT told the Bureau: “We are clear that our products are for adults only and that youth should never use any tobacco or nicotine products.”

Lawyers from Imperial Tobacco, the maker of JPS and Lambert & Butler, repeatedly wrote to PHE and quizzed it about the legality of the delay. Both companies have commissioned research that they claim shows JTI’s cigarettes to have a characterising flavour, the results of which they have shared with PHE.

But despite its repeated complaints, it appears that Imperial Tobacco too may be under scrutiny. PHE requested more information about a number of cigarette brands the company launched under its new “Green Filter” range, which it said were “designed specifically for [menthol consumers]”. PHE reminded the company that “it is a criminal offence to breach these regulations”.

Imperial Tobacco told the Bureau: “Menthol is not an ingredient used in any of our current UK cigarette offerings […] and we always comply with legislation. Children should never use our products.”

What makes a cigar a cigar?

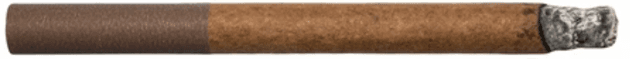

Alongside its New Dual cigarettes, JTI started selling menthol cigarillos – short, narrow cigars – in the run-up to the ban as part of its “menthol reimagined” campaign. In a brochure distributed to retailers around the time of the ban and seen by the Bureau, JTI said the “look, feel and smoking experience” of the new cigarillos will be “comfortingly familiar” to menthol cigarette smokers.

By law, what distinguishes a cigar is that it is wrapped in tobacco leaf. Crucially, cigars and cigarillos are exempted from many of the rules applied to cigarettes – including the menthol ban.

Researchers at the University of Bath took apart a JTI cigarillo to see how it compared with a conventional cigarette. The only notable difference was that the cigar was wrapped in tobacco leaf rather than a white paper – but on opening they found there was also a paper tube within the leaf wrap to hold the tobacco.

This seems to have come as a surprise to someone in JTI’s offices. “Presumably there are other changes beyond the leaf,” a JTI employee had written in notes sent to the Bureau, perhaps inadvertently, after we put it to the company. Next to our claim that the menthol cigarillo has a paper tube, like a cigarette, within the leaf wrap to hold the tobacco, JTI’s notes read: “Does it – check with UK M&S [marketing and sales]?”.

In its official response, JTI said: “There are a number of differences between cigarettes and cigarillos. Unlike cigarettes, cigarillos are wrapped in tobacco leaf or tobacco-based paper.”

Notes by a JTI employee on the document it sent back to the Bureau

Notes by a JTI employee on the document it sent back to the Bureau

JTI sales representatives told shopkeepers in the UK to stock the new cigarillos, which have a distinct menthol flavour, ahead of the ban. In May 2020, when the ban came into force, sales of cigars and cigarillos at corner shops in the UK increased significantly, according to data from the New Retail Data Partnership. The bump in sales was almost entirely driven by JTI’s new menthol cigarillos.

One shopkeeper told the Bureau the new menthol cigarillos were “popular because they're much cheaper” than cigarettes. Cigarillos are taxed lower than cigarettes and can also be bought in smaller 10-packs, which were banned for cigarettes in 2017.

Based on analysis by the University of Bath, the Bureau calculated that a pack of 20 cigarillos could be taxed almost £2 less than a pack of 20 cigarettes. It appears this saving is passed on to the customer – JTI’s Sterling Dual Capsule Leaf Wrapped sells for about £9, more than £2 cheaper than the average pack of cigarettes.

For “menthol seekers”, Imperial Tobacco launched new “flavour cards” under its Rizla brand. They can be inserted in a regular pack of cigarettes to impart a menthol flavour. They are sold individually for just 25p. It also started selling a similar menthol cigarillo shortly after the ban came into force.

Reaching the next generation

With Brexit meaning that the UK is no longer subject to EU tobacco regulations, JTI has taken the opportunity to lobby for a relaxation of the menthol ban. The company claims that the new rules have had “little impact on smoking cessation”.

Preliminary data from University College London suggests a quarter of 16 to 24-year-old smokers still smoke menthol tobacco. The researchers conclude that this is likely due to the variety of alternative products the industry promoted prior to the ban.

Sterling's Dual Capsule Leaf Wrapped cigarillos, launched in January 2020

Sterling's Dual Capsule Leaf Wrapped cigarillos, launched in January 2020

Rizla's new flavour cards, "designed for menthol seekers"

Rizla's new flavour cards, "designed for menthol seekers"

JTI said: “We have always strongly maintained that minors should not smoke and should not have access to tobacco products. We also do not believe that cigarettes with a characterizing flavor of menthol are appealing to minors.”

Although it is too soon for reliable data on the impact of the menthol ban – described as “not a real ban” by one shopkeeper – Arnott is concerned about what the industry’s efforts to undermine it might mean for efforts to curb youth smoking.

“The government is currently reviewing the regulations and we’ve strongly recommended that all flavours should be banned in tobacco products, which could be achieved very simply by removing the word ‘characterising’ from the regulations,” she said.

Additional reporting by Sarah Haque

Reporters: Ben Stockton, Laura Margottini, Alessia Cerantola and Andrei Ciurcanu

Additional reporting: Sarah Haque

Impact producer: Paul Eccles

Desk editor: Chrissie Giles

Global editor: James Ball

Editor: Meirion Jones

Production editor: Alex Hess

Fact checker: Alice Milliken

Legal team: Stephen Shotnes (Simons Muirhead Burton)

Our reporting on tobacco is part of our Global Health project, which has a number of funders. Smoke Screen is funded by Vital Strategies. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.

Header image: A shelf displaying Benson & Hedges cigarettes, one of the brands owned by JTI. Credit: Alamy