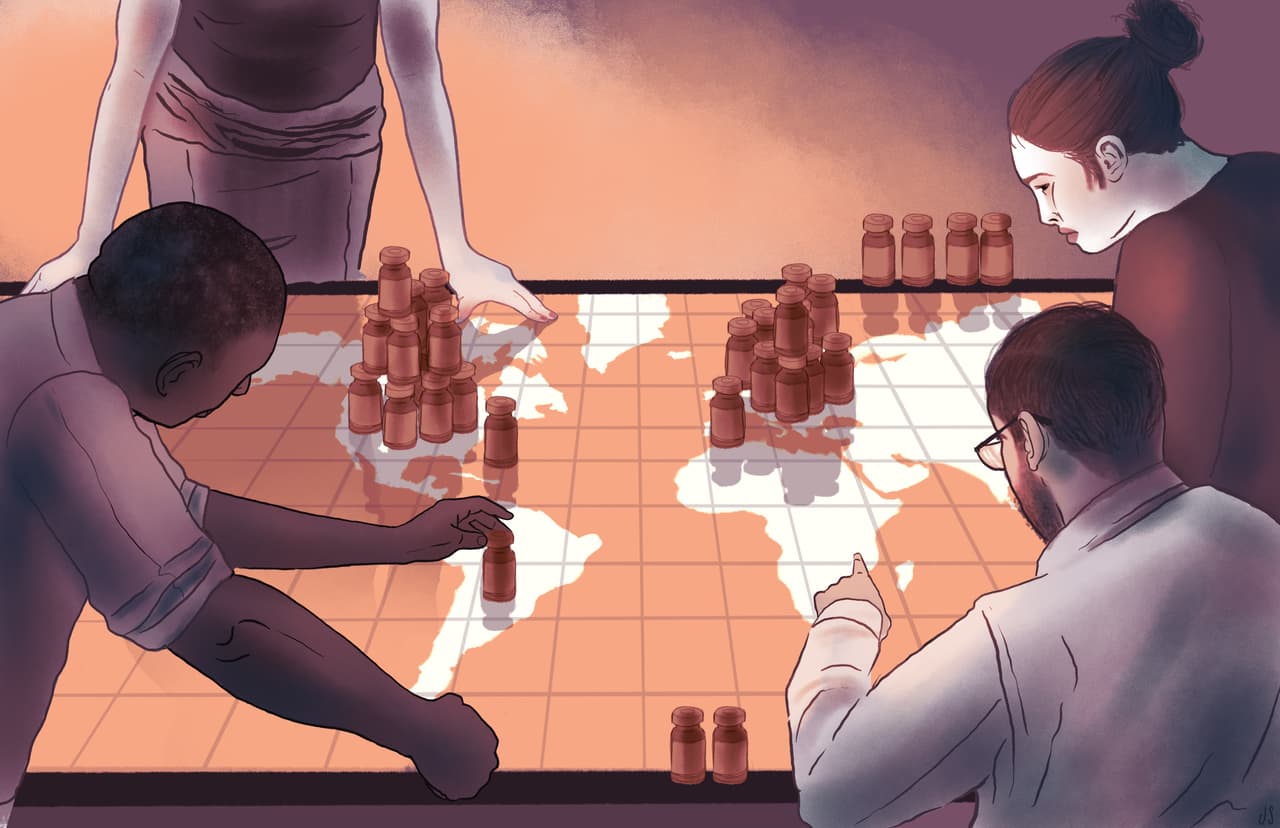

How Covax failed on its promise to vaccinate the world

The ambassador felt her heart sink as she read the email. Later she would recall this moment as the worst situation she’d faced since arriving in Geneva. Gripped by the pandemic, her country had received many thousands of free Covid-19 vaccines in early 2021. But the supply had rapidly depleted. The shots had come from Covax, the ambitious global collaboration set up to give people in rich and poor nations equitable access to vaccines.

Now, in April, Covax was telling her the next delivery wasn’t coming yet. What would happen to the doctors, nurses and grandparents waiting for their second shots?

Over the next few weeks, the ambassador and her colleagues tried everything to get more vaccines for people in their large, developing country south of the equator. She repeatedly called her Covax coordinator, but they wouldn’t put her in touch with the manufacturers and couldn’t tell her when more doses would arrive. She tried to contact Covax executives directly, to no avail.

Running out of options, country officials called their counterparts in other governments to try to negotiate deals. They were in dire financial straits but the situation was desperate. “We were begging for an answer,” she said.

Conceived at the start of the pandemic, Covax pursued lofty goals, promising fair access to Covid-19 vaccines for every country worldwide, and to give them free to the poorest. For richer nations, Covax said it would act as an insurance policy. For poorer ones, a lifeline.

Stark reality

But the first 18 months have not gone as hoped. As richer countries roll out booster shots, 98% of people in low-income countries remain unvaccinated. Covax, described as “naively ambitious” by one expert, has contributed just 5% of all vaccines administered globally and recently announced it would miss its 2 billion target for 2021.

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism and STAT have reviewed confidential internal documents and spoken with officials from more than two dozen countries, many of whom described confusion and frustration with Covax. Although grateful for what the initiative is trying to do, they say they’ve struggled to get information from Covax personnel and been left in the dark over when, if ever, deliveries would arrive.

Countries have received supplies months late or with little notice, throwing vaccination campaigns into chaos and sometimes delaying people’s second doses. In some cases, short-date vaccines were returned or thrown away after governments were unable to distribute them in time. Countries and regions with the financial means to do so then scrambled to make deals with vaccine manufacturers directly, but found themselves at the back of the queue.

Covax has been accused of sidelining the organisations that represent the interests of poorer nations in its top-tier discussions, denying a voice to those who were most desperate.

Some officials spoke to us on the condition of anonymity, fearful that openly discussing their experiences with Covax could harm their relationships with the organisation.

Many of the concerns identified in this investigation have been reflected in a review commissioned by Covax’s umbrella organisation. A draft version was seen by the Bureau.

The review highlighted the “insufficient inclusion and meaningful engagement” of low- and middle-income countries, civil society organisations and community representatives. Additionally, it noted concerns that Covax isn’t doing enough to expand vaccine production through measures such as technology transfer, and that health systems will “need support” in the coming months to roll out increased supplies of vaccines.

Covax told the Bureau that the initiative is breaking new ground in facilitating access to Covid-19 vaccines for all, including creating the “world’s first global allocation mechanism based on principles of equity and fairness”.

Covax said that estimates of the number of doses and availability are based on information received from manufacturers, and that “because of delays in the release of vaccines from manufacturers, it has not always been possible to notify countries a long time in advance” about supplies.

It acknowledged that, “while the mechanism is now working at scale, volumes made available to it to date are unacceptable”. It calls on manufacturers and governments “to prioritise Covax so it can urgently accelerate deliveries to countries that need doses most”.

Covax has delivered some 330 million vaccines so far, yet now intends to distribute a massive 1.1 billion vaccines in just the next three months. Some officials in poorer countries fear that the abrupt surge could overwhelm their health systems and lead to much-needed vaccines going to waste.

As a vision of solidarity to an operation based on charity, Covax has failed to live up to its promise. Eighteen months since the initiative launched, countries in the global south continue to face devastating Covid-19 waves and billions of people remain unvaccinated. Experts say that Covax must reflect and learn from its mistakes to change the direction of this pandemic – and apply vital lessons before the next.

A chance to change

In January 2020, at a bar in the Swiss mountain resort of Davos, Seth Berkley and Richard Hatchett were discussing the growing crisis in Wuhan, China. Berkley is the CEO of Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance, a public-private partnership that aims to improve access to immunisations in developing countries. Hatchett is head of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (Cepi), a foundation that finances the development of vaccines to stop epidemics.

Cepi had already made its first deals to fund three candidate Covid-19 vaccines through early human clinical trials, anticipating a global emergency. In Davos, Hatchett recalled: “[We] talked about our concerns about ensuring equitable access to any vaccines, if what we thought might be happening transpired – which was it might evolve into a pandemic.”

After witnessing the White House’s response to the 2009 swine flu epidemic, when wealthy nations snatched up vaccine supplies, Hatchett knew a similar reaction to Covid-19 would mean disaster for much of the world. To avoid that, he told Berkley, they needed to “try to create a globally inclusive system that serves everyone’s needs”.

Two months later, Hatchett shared a proposal for the initiative that would become Covax. It would be an end-to-end programme – spanning vaccine development to delivery – for every country in the world. By investing in several candidate vaccines from different companies, Covax would improve its chances of having a successful vaccine when trials concluded. Buying doses in bulk meant Covax could negotiate favourable prices with manufacturers.

High- and middle-income countries would buy into Covax, while poorer ones would receive vaccines for free, funded by donations from wealthy governments and charities, for up to 20% of their population. As a clearing house, Covax would allocate vaccines fairly across the globe, shipping them to rich and poor countries simultaneously. Such a system could be established fairly straightforwardly, the proposal said, “with sufficient political will and public sector financing”.

But Covax was short on both. To work, it would require the cooperation of rich governments whose impulse would be to buy up as many vaccines as possible to protect their own citizens – even as they stood to benefit from the reduced risk of Covax’s vaccine portfolio. And the initiative would need substantial funding, at least $2bn, to make early investments in candidate vaccines and get access to the ones that made it through trials.

Covax was launched in April 2020 as part of a global partnership known as the Access to Covid-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A). Covax would handle vaccines, led by Cepi, Gavi and the World Health Organization (WHO), with Unicef leading delivery efforts.

Covax is co-led by Cepi, Gavi and the WHO. Unicef assists with the procurement of vaccine doses, freight, logistics and storage

Covax is co-led by Cepi, Gavi and the WHO. Unicef assists with the procurement of vaccine doses, freight, logistics and storage

But even at this stage, there was disquiet about Covax’s design. After meeting with Hatchett in March, Els Torreele, then the director of Médecins Sans Frontières’ (MSF) access to essential medicines campaign, had been sold his idea of a collective end-to-end global programme. Now, to her, Covax looked “watered down” to just an allocation mechanism.

In comments sent to Cepi in early April, she pressed the need for Covax to push hard to get manufacturers to agree up front to give them global access to vaccines if trials were successful, and to invest in expanding global manufacturing infrastructure immediately. She also urged Covax to be fully accountable and transparent about contracts and prices. “But clearly the train had left the station,” she said.

Once established, Covax had only a small window of opportunity to sign up wealthy countries before national governments began buying their own vaccine supplies.

John-Arne Røttingen, a Norwegian medical scientist, civil servant and Gavi board member, said Covax missed an opportunity to sign up Europe early in 2020. “Europe was not organised at that time. They had not decided on a model,” he said. “We definitely tried to sell the idea not only as a joint procurement mechanism, but as a risk-sharing mechanism.

“I had a couple of conversations with countries where we tried to make them form some sort of alliance,” he said, but added that the governments weren’t ready to put their faith in the idea of Covax.

Then, in May, the Trump administration launched Operation Warp Speed, officially signalling the United States’ unwillingness to enter a global collective. “The Americans didn’t want to play,” said Torreele.

Covax said it never expected Europe or other high-income countries to refrain from making bilateral deals. However, it said it “anticipated that they would join as a risk-mitigation measure, given that at the time Covax was designed, all vaccine candidates were unproven”.

“Covax really was flawed in the beginning,” said Kate Elder, a senior vaccines policy adviser at MSF’s access campaign. “I think it was naively ambitious.”

Others agree. “Covax probably overestimated the amount of vaccines they were going to get and the speed at which they were going to get them,” said Mauricio Cárdenas, a member of the WHO’s Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response. “And they basically told that story to the countries.”

Covax takes flight

On 24 February 2021, 10 months after Covax’s launch, a plane carrying 600,000 doses of vaccine landed at Kotoka International Airport in Accra, Ghana. Covax’s first international shipment had officially arrived, on time, but still some three months after the UK vaccine rollout had begun.

Covax was in business. Over the next six weeks, it shipped 38 million doses around the world. Although it had planned to use multiple vaccine manufacturers, nearly three-quarters of these initial doses came from a single company in western India. Gavi had a longstanding relationship with the Serum Institute of India (SII), and had signed an agreement for it to supply Covax with 1.1 billion doses. More than 110 million were due before May 2021, destined for lower-income countries.

But in March, disaster struck. India suffered a sudden, devastating wave of Covid-19 infections, and the country imposed a de facto ban on vaccine exports. Gavi announced that Covax would face delays on up to 90 million doses during March and April. In Geneva, the ambassador grew frantic.

Experts say this shouldn’t have come as a surprise to Covax. A confidential briefing by Unicef in the previous summer noted that Covax was potentially too dependent on Indian manufacturing. Yet it seems no changes were made. “They should have seen this coming,” said Hitesh Hurkchand, an epidemiologist and expert on pharmaceutical supply chains. “Where was the risk analysis?”

Covax said that “it was natural that SII was contracted to supply large volumes” of vaccines to the initiative, because “all other capacity [was] already pre-ordered by high income countries, and because of SII’s significant manufacturing capacity and its proven ability to deliver affordably”.

Delays mounted. Country officials around the world said that since April, many Covax deliveries have arrived weeks or months late.

For countries like the ambassador’s, where people were waiting for their second doses, the result was chaos. Country officials faced a dilemma: to give people their first vaccine and hope subsequent deliveries arrived in time for the second shots, or to hold back doses from the same delivery to cover the first and second for half the number of people – if expiry dates allowed.

In Gambia, officials came under pressure to find second shots. “People were calling us every day for vaccines,” said Mustapha Bittaye, director of health services at the Gambian Ministry of Health.

In Nigeria, Namibia and Afghanistan, late deliveries had a knock-on effect for state-led vaccination awareness campaigns, harming efforts to increase uptake. Nigerian Ministry of Health vaccination lead Dr Faisal Shuaib said the lack of shots allowed misinformation, including claims that future vaccines would be tainted, to thrive. “Because the vaccines were delayed,” he said, “those conspiracy theories became more widespread.”

Ben Nangombe, Namibia’s executive director of health, said people in his country had travelled long distances only to find vaccination centres had not received the expected doses. “They won’t come back,” he said.

A senior Pakistani government official said the impact of India’s export ban had shaken faith in Covax. “We’re really worried that it could disrupt our [vaccination] plans again,” he said.

Like some other middle-income countries, Pakistan made its own deals with vaccine manufacturers when it became clear Covax could not deliver. This process was made harder because many richer countries had already made deals, leaving latecomers at the back of the queue.

An official from one Latin American country described the potential political fallout of late deliveries: “How are we going to justify that you put so much money upfront and still you have not received what was promised?” Delivery delays also forced this country to make direct deals with manufacturers.

Tatiana Molcean, Moldova’s ambassador to the UN, described an “embarrassing situation” in which she praised Covax during a meeting with the WHO, but was followed by “speeches from several ambassadors from different countries saying they had [received] no information”. She said: “It was painful to see that when we were already receiving a few batches, they were still struggling.”

As delays from India dragged on, Covax scrambled to make up its shortfall. Internal supply forecasts from April 2021 showed Covax expected Indian manufacturers to provide most of its supply until September: up to 560 million doses. Two months after India’s ban, a confidential report to investors showed that Covax was pursuing “various mitigation strategies”, including diversifying its vaccine sources.

But moving away from Indian manufacturers would mean higher prices, the report noted. SII vaccines cost Covax about $3 a dose. The average prices offered to Covax for non-Indian candidates were “50-100% higher”, according to the report.

Covax said that “while important, price has never been the only consideration when making procurement decisions”. It added that as new vaccines are approved they become available through the Covax portfolio and that 400 million doses of the new Chinese vaccine Clover have been secured. Covax said it hoped these would become available before the end of the year.

In late September, six months after imposing its export ban, the Indian government announced it expected to restart shipments to Covax in October. But some believe the damage has been done. As one logistics expert said: “Because of Covax’s decision to put all their eggs into one basket, people did die.”

Desperate for answers

Problems with deliveries were compounded by miscommunication. Many officials said they were unable to get adequate answers from Covax about when doses might eventually arrive. Covax had coordinators to liaise with country officials, but some officials said they found it difficult to get clear information. “They talk about having issues with producers, but they don’t specify details,” a Latin American official said. “All the time, we are asking when vaccines will be delivered, and they don’t give us a precise answer.”

Relations with Libya’s Covax coordinator got “a little ugly” at times, said Tamim Baiou, Libya’s UN ambassador. Baiou said his country’s request for a meeting with Berkley was met with silence.

Covax said it had not received the request and would be following up with the Permanent Mission of Libya.

Officials from other countries questioned whether Covax’s coordinators withheld information purposely, or whether they were also being kept in the dark. One ambassador from a small European country described how she had sometimes been given conflicting information from different people inside Covax.

As Pakistan pressed for answers, the official said Covax would “sometimes not pick up the phone”. When he did get through to a Gavi executive, he said he could “sense the feeling of helplessness”. Repeatedly, Covax told countries they were aware of the difficulties, and were doing what they could.

Dr Sabin Nsanzimana, the director general of the Rwanda Biomedical Centre, said Covax had given his country just days’ notice of a shipment arriving. “We had to run to the airport in the morning,” he said.

When doses did arrive, some were close to expiring. For nations with weak health systems, this presented a considerable challenge. In East Timor, doses from Covax had to be destroyed because they had expired or were damaged because of a lack of freezers.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo eventually returned more than a million doses to Covax after being unable to use them before they expired. South Sudan also returned vaccines. Covax said most of the “doses from DRC and Sudan were successfully redeployed to other countries in Africa”.

Not being able to give long-term predictions to countries is “very frustrating”, Seth Berkley said. But he maintains that Gavi had communicated the information it could. “It’s so complex, we could talk every day and not bring everybody on board.” Covax added that it has maintained “regular communication” with countries, “including with respect to changes in supply volumes, schedules and timelines”.

But the Bureau has learned that some communication issues remain. A Latin American health official said their government wrote to Berkley a month ago demanding an explanation for why their Covax doses had not yet been delivered. They have not received a reply.

Meanwhile in Somalia, one health official said Covax supplied vaccine doses but not syringes or other equipment needed to administer them. The country is having to use stockpiles of syringes normally reserved for childhood measles vaccination campaigns.

The official said he fears interruptions to routine immunisations during the pandemic make a large measles outbreak possible – and the lack of syringes could be disastrous.

Covax said that countries eligible for vaccines “are also eligible for safe injection equipment”. It said it is aware that some countries may use routine stock as a “temporary bridge until additional supplies become available”, and it is unaware of any risks to any immunisation activities in Somalia due to equipment shortages.

The Somalian official said that although emergency paperwork for extra funding for syringes and other rollout costs was sent to Covax in mid-August, he has yet to receive a response. When he followed up, he said he was told: “Oh, it’s a holiday time.”

From solidarity to charity

Stymied by events in India and short on vaccines, in May 2021, Covax tried a new tactic. Wealthy countries had bought far more vaccines than needed. Even accounting for booster shots, one internal Covax document noted these countries collectively would likely have between 1 billion and 5 billion doses to redistribute – mostly from the US and EU. “The time to donate excess doses,” Unicef implored, “is NOW.”

But countries were slow to take up the call, even as they continued to make their own deals. Canada had bought enough vaccines to inoculate its population five times over, but only shipped its first donations last month. The bulk of those doses went to Nigeria, which was already in the grip of a third coronavirus wave. The US promised 200 million doses by the end of the year, but missed its first target. In September, US president Joe Biden announced a further 500 million doses would be donated to developing countries in 2022.

In total, wealthy countries have pledged to donate roughly 785 million doses to Covax as of 24 September. But just 18% have arrived, according to figures compiled by Our World in Data.

At the same time as promising donations, some wealthy countries have dipped into Covax supplies themselves. The UK, Canada and other rich countries have all received Covax doses in 2021. In June, Covax sent some 530,000 doses to the UK alone. The entire continent of Africa received only four times that amount in the same period.

As with some doses sent directly from Covax, recent donations from Canada and the UK through Covax arrived in African countries just weeks before expiry.

Analysis by scientific research group Airfinity found that more than 100 million vaccines held by G7 nations and the EU are to expire by the end of the year, and need to be redistributed immediately. Covax said it was “committed to letting no doses remain idle wherever possible”, and it tries “to identify countries that are able to absorb rapid deliveries”.

Internally, Covax has also expressed concerns over the additional cost burden of donations. On a call with ACT-A leaders in July, Berkley said some donors were not funding “fringe costs” such as freight and transportation, leaving Covax to pick up the tab. “Covax is appealing to donors to cover these aligning costs and also working with countries to understand more precisely the timing of donations,” the minutes noted.

Ultimately, donations have not made up for Covax’s shortfall. By early October, Covax had shipped about 330 million of its 2 billion planned doses, 40% of which were donated. “I do not believe donations is the way we should be dealing with a health crisis like this,” Berkley told the Bureau. “What we need is to get those deals locked in and to make sure that manufacturers will deliver on time.”

“You can’t charity your way out of a pandemic,” Elder of MSF said. “This is why rebalancing between corporate interests and the public’s interest is so important.”

Airport workers in Antananarivo, Madagascar, unload a Covax delivery

Mamyrael/AFP/Getty

Airport workers in Antananarivo, Madagascar, unload a Covax delivery

Mamyrael/AFP/Getty

Shortfalls and shortcomings

With frustrations mounting, some advocates have accused Covax of taking a “business as usual” approach to an unprecedented global emergency.

“The foundational flaw for me is the fact that they did not put around the table the low- and middle-income countries,” said Dr Joanne Liu, the former international president of MSF. As a product of the western-led global health system, she believes there was the sense that Covax could not find the time to or was not interested in listening to the needs of poorer countries, and was instead telling them to be grateful for what they were being given. “That country club mindset needs to change.”

Poorer countries and civil society organisations were not consulted adequately in Covax’s design process, according to MSF, and Covax was the last ACT-A pillar to nominate representatives of these organisations to its working groups. “Initially, they blocked us,” said Mike Podmore, who represents non-profits in ACT-A. It took “a lot of advocacy and pressure”, he said, before Covax agreed to let them in. Even then, insiders said, it seemed like Covax attempted to control the nomination process.

Once the representatives arrived, things didn’t improve. Some told the Bureau that Covax was unwilling to listen to them. “In the first meeting, I was shocked,” said Rudelmar Bueno de Faria, who joined a Covax working group in April as one of two civil society representatives. “I did not even have access to the chat in Zoom.” Other representatives confirmed that they could not unmute themselves to give feedback during online meetings.

Silenced in meetings, Bueno de Faria said he submitted comments ahead of calls, but they were not acknowledged. Other representatives said they felt as if decisions had been “pre-cooked” before meetings began. Representatives said Covax had sent out documents just 24 hours before calls. Podmore said this effectively eliminated representatives’ ability to consult or provide meaningful feedback. “They’re just lucky if they can actually get through the slide decks,” he said.

The issue goes beyond optics. Without global south perspectives in the room, advocates said Covax has blindspots. “Priorities are totally distorted. You don’t get a sense of the weight of what’s happening in-country,” said Dr Fifa Rahman, a civil society representative on the ACT-A facilitation council. “If it’s not inclusive, it’s not going to be effective.”

Bueno de Faria is concerned that his expertise on combating vaccine hesitancy – an issue high on Covax’s agenda – is not being fully used. He is considering stepping down. “If we will be mere spectators, I don’t want that position,” he said.

Covax said it takes civil society organisations’ input seriously and holds regular calls with individuals from more than 100 organisations. It said it has had “considerable positive feedback” from a variety of these groups, and had not heard about issues with unmuting.

Covax has also come under scrutiny for its close ties to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. (The foundation is one of the Bureau's funders). Two of Covax’s three leaders, Cepi and Gavi, are backed by the Foundation and some question whether Gates’ involvement might have led Covax to take a less radical approach to vaccine distribution – particularly regarding Covax’s stance on intellectual property (IP) laws.

Covax’s timid approach to issues such as sharing vaccine technology and know-how with global south manufacturers has infuriated advocates, who believe lifting IP rights could radically increase manufacturing and get vaccines to poorer countries faster. But many western nations have refused to back even a temporary lifting of IP laws, and neither Cepi nor Gavi has publicly supported the idea.

The Gates Foundation said the primary barriers to vaccine access it has identified include “financing, limited tech transfer, constraints on raw materials, and nationalist policies that have kept doses concentrated in a few high-income countries”. It added that “Covax is breaking new ground in facilitating access to Covid-19 vaccines for all”.

“Their whole premise is about public-private cooperation,” said Katerini Storeng, an associate professor at the University of Oslo who has researched Gavi and Gates’ approach to improving global health. “And if you’re trying to cooperate with people, you don’t enter into a revolution, do you?”

A winter surge

After suffering severe delays through the summer and downgrading its overall delivery target for 2021, Covax is planning to send more than a billion vaccines to poor countries in the last three months of 2021. One internal Covax document shows health systems will need to deploy nearly twice as many Covax doses as they have in the previous three months.

While countries that have been anxiously waiting are grateful they will soon receive much-needed doses, some are concerned about handling the influx from Covax. One Latin American official described his country’s expected allocation – well over 10 million doses – as “a huge amount”, especially given the timing. “We’re going to have huge issues trying to get those vaccines in people’s arms by the end of the year during Christmas festivities.”

Covax said it is working hard with health ministries to ensure countries are ready to receive these doses, but that its remit does not include vaccine rollout. “Our goal is to try to empower countries to do a good job,” Berkley said. “We can help, but we can’t make that happen.”

In a statement, Covax added that “some levels of wastage are to be expected across all immunisation programmes”, and it expects “wastage to increase when supply ramps up”. It is calling on development banks to unlock funding and ensure countries avoid problems such as expiry and wastage.

But Covax’s reputation is on the line, experts said. “They are under the gun to deliver,” said Hurkchand, the supply chain expert. “The likelihood of wastage is very high.”

The damage to Covax’s reputation may have already been done. In June, a report to the Gavi board said Covax anticipated “many” self-financing countries would decide not to get doses through Covax in 2022. In August, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), an international global health agency, announced that it would begin to buy vaccines itself.

PAHO assistant director Jarbas Barbosa said the initiative was “not to replace Covax but to complement” it. But others note that the region has suffered heavily during the pandemic, and many Latin American countries have made vaccine deals with countries and companies to make up for Covax’s shortfall – in essence, buying twice.

“We signed an agreement for a certain amount and we had to pay, we have obligations,” said Uruguay’s UN ambassador Álvaro Moerzinger Pagani. “But Covax did not deliver in an appropriate manner. Covax did not comply with the agreement.”

Lawrence Gostin, a professor of global health law at Georgetown University, said hundreds of thousands of people who died in Latin America could have been saved by Covid-19 vaccines. “PAHO took the decision that, as much as they believe in Covax, they could do a better job,” he said.

PAHO’s decision was not without precedent. The African Union previously set up the Africa Vaccine Acquisition Task Team to reach 60% coverage on the continent by 2022. Unicef and Covax said they are focused on delivering vaccines to Africa through all available channels.

Yet, despite friendly appearances, one insider said it seemed a “turf war” between players on the continent may be damaging access efforts. “At a tactical level, you need these individuals, you need these agencies, sitting together and planning,” he said. “That has not happened, period.”

Facing the future

Covax has shipped doses to 144 countries – but some have received less than half of what they were originally allocated.

Covax is clear on who’s to blame for the shortfall: vaccine manufacturers. “There’s no transparency on where we are in the queue,” Berkley told the Bureau. While some manufacturing delays were certainly legitimate, “the question is, are they equally affecting all of their customers? Or are they saying, ‘Gee, we’re going to have more political pressure from high-income countries, and therefore we’re going to allow [Covax] to slip down the pipeline.’”

Dr Kate O’Brien, director of the WHO’s Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals, agrees: “It would be probably fair to say that it’s the manufacturers who allocated vaccines globally.”

But while manufacturers are falling behind on their Covax orders, advocates said Covax shouldn’t be absolved of all failings. “I don’t think that manufacturers’ behaviour, which has been tested time and time again and always delivered the same thing, is uniquely why Covax is not delivering,” Elder said. “I think there was plenty that was under the control of the architects of Covax which was a misstep.”

The scheme’s concept was good, but it “failed miserably” in practice, Libya’s UN ambassador Baiou said. “I can’t understand and don’t understand why Covax would enter into these agreements when it did not address how to control the supply of vaccines.”

Torreele sees it as a missed opportunity. Rather than transforming the way we develop and share life-saving medicine in an equitable way, she says, “We’re back to what we’ve always done.”

Ultimately, advocates and officials in low- and middle-income countries agree: vaccine shortages and unfair distribution have not been fixed by Covax, and more must be done before the next pandemic.

One Latin American health official considers the grave consequences of not having other supplies on which to fall back. “If we didn’t have bilateral agreements, it would have been catastrophic.”

Reporters: Rosa Furneaux, Olivia Goldhill and Madlen Davies

Impact producer: Paul Eccles

Desk editor: Chrissie Giles

Global editor: James Ball

Investigations editor: Meirion Jones

Production editors: Alex Hess, Emily Goddard and Frankie Goodway

Fact checker: Alice Milliken

Legal team: Stephen Shotnes (Simons Muirhead Burton)

Illustrations: Jess Suttner

A version of this article also appeared in Quartz.

This article is part of our Global Health project, which has a number of funders including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.

-

Area:

-

Subject: