No Fixed Abode: how a simple question became a year-long investigation – and then a book

The number of people sleeping rough for the first time went up during the pandemic – reporting on homelessness is far from over

I thought it was a simple question. Back in the winter of 2017, I became fixated on one issue: homelessness. Rough sleeping to be more precise. Scrolling through my Twitter feed I had started to notice a few stories, horrific tales of people dying while on the streets. Each article would be accompanied by some small outcry, a few angry voices from local campaign groups… and then little more.

I knew that homelessness had been growing across the UK – the number of people sleeping rough rose by 169 per cent between 2010 and 2017. Though I didn’t need the data to tell me that: my daily walk from the Tube station to my office had become punctuated by the sad sight of people sitting or sleeping on the streets.

And yet it was an issue that very few people were talking about. It seems ridiculous in retrospect: the Covid-19 pandemic has made it abundantly clear how a safe space to call home can be a matter of life and death. Indeed, the push to get many of those sleeping rough off the streets no doubt saved lives. But before the outbreak of the virus, not many people gave much thought to how and when people were dying while homeless.

So those articles had provoked a question: if we knew more people were living homeless, were more people dying that way too?

Weeks later, I was no closer to an answer. I had tried calling everyone I could think of: coroners’ offices, hospitals, police forces, councils, central government departments – each time the voice on the other end of the phone would explain that they did not have the data but surely someone else had. It turns out that they were wrong: no one was keeping any kind of centralised count of how and when people were dying while homeless.

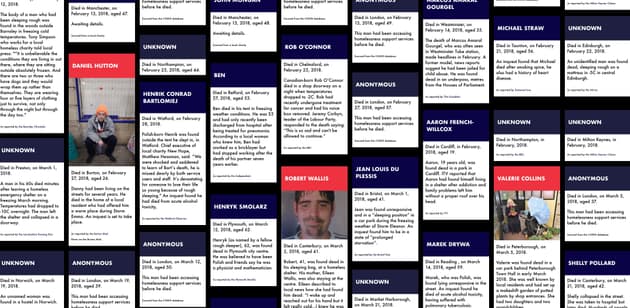

Thus began a year-long project we called Dying Homeless. Working with our Bureau Local network of journalists and citizens across the UK we pulled together the details of 800 people who died over the course of a year and a half. Together we published more than 180 news pieces on the topic, and people began to take note.

We started our series using the hashtag #makethemcount: a call for an official body to log these deaths. In December, prompted by our work, the Office for National Statistics produced the first ever official data on homeless deaths. This came after we opened our database to the ONS to help it develop its methodology. Our work was cited heavily in its release. The Scottish National Records Office has now followed suit and produced its own data too. We handed over the project to the wonderful people at the Museum of Homelessness and are proud to see the work to record and raise awareness around homeless deaths continue.

But I knew there was more to dig into, more stories to tell. Which is when I decided to write a book.

Detailing the lives and work of more than a dozen individuals, No Fixed Abode is the product of nearly three years of research. Through the stories of those living homeless, their families and the people working to support them, the book charts how the safety net we expect to save us all fails time after time.

The Bureau launches 'Dying Homeless' project to count deaths on UK streets

The Bureau launches 'Dying Homeless' project to count deaths on UK streets

While researching the book I was often shocked at just how fragile the system is, how easy it is to fall through the net. Budget cuts to mental health services, substance abuse treatment programmes, the freeze on housing benefits, the hostile immigration environment and spiralling private rents have all culminated in a perfect storm, leading inevitably to the homelessness crisis that we see today.

I spent weeks and then months checking in with people, shadowing them as they went about their work, visiting squats, sitting quietly in the back rows of funerals, scribbling notes at inquest hearings, and watching hastily prepared lawyers tell of terrible violence in murder trials. I found myself in GP waiting rooms and hustling my way into council offices.

And on the way I met extraordinary people: people like Jon, who spends every free minute organising meals and accommodation for those at risk; or Pam, who fought for years to try and support her daughter and save her from the streets; or Alfie, who only wanted to get back to his own flat before his terminal illness claimed his life.

I saw how every strand of the safety net meant to support these people had been worn away. I feared for their future. And then the pandemic hit.

Almost overnight the world changed. At first there was a glimmer of hope: plans and policies on homelessness were implemented with unprecedented speed. But soon the concerns crept in…

The Bureau has reported how the long-term funding for those housed under the pandemic is not secure and while migrants are estimated to make up 60 per cent of the emergency homeless population during Covid, they currently do not have access to public help once the emergency funds end. Additionally, evictions are soon to start up again, bringing a wave of new homelessness across the country. In London, the number of people sleeping rough for the first time between April and June was up by 77 per cent on the same period last year.

Now the country is at a crossroads, but unless we learn from the mistakes of the past, we will never know how to build back better. My hope is that our Dying Homeless project and the work I have done since can go some way to highlighting the mistakes of the past and providing some solutions for the future.

No Fixed Abode: Life and Death Among the UK's Forgotten Homeless by Maeve McClenaghan builds on our Dying Homeless project to give a deep and intensely human insight into how we have got to this point, and how we can find our way back.

Our reporting on the housing crisis is part of our Bureau Local project, which has many funders. Our work on the housing crisis was supported by the Bertha Foundation. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.

Header illustration by Andrew Garthwaite