Taxpayers handing millions to private companies for housing the vulnerable

Ben’s journey to getting his own home has been fraught. The 26-year-old is autistic and has spent much of his adult life sectioned, pinballing between hospitals and police cells, as his mother struggled to get him the right support. At one point, he ended up comatose in psychiatric intensive care for four days after a massive injection of antipsychotic drugs. The council eventually found Ben* a home, and in early 2019 he moved into a block of flats in north-west England that was meant to be designed for people like him.

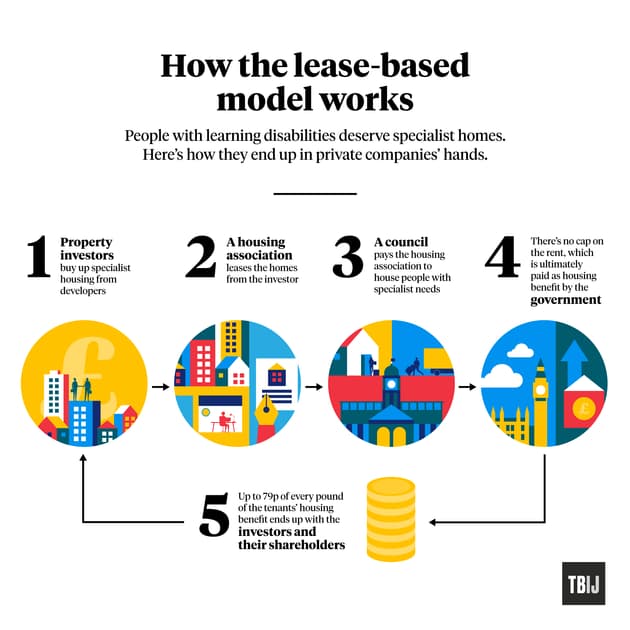

But it is not the council that owns his home – it belongs to a company called Civitas Social Housing (CSH), which is listed on the Stock Exchange and has a property portfolio of homes like Ben’s worth £878.7m as of March this year. Every week, the council transfers £276 – in the form of housing benefit – to Ben’s housing association, which in turn pays Civitas a lease payment for owning the building.

Housing associations (privately run non-profits) up and down the country have signed leases with companies such as Civitas, which have ended up making millions by providing homes for vulnerable people. This year, Civitas distributed a total of £33m to their shareholders.

The Bureau has found that up to 79p in every pound collected in housing benefit goes back to such companies before housing associations can fulfil their other obligations, such as making home repairs or ensuring safe conditions. The Bureau is publishing the full list of housing associations entangled in this model and has found evidence that in some cases they have been charging disproportionately high rents to cover the lease payments, with families describing the costs as “unjustifiable” for what is provided. The model has raised concerns at the industry regulator that not enough money is being left for the housing associations to run effectively.

According to his mother, Ben’s new home is not a suitable placement. The flat is located on a busy road, with sirens frequently blaring past. The police are often called out to his block of flats, which terrifies him because of his past experiences. “He keeps telling people he wants to leave,” his mother told the Bureau. She said he feels that “it is very institutional”.

How we got here

Since the Winterbourne View scandal in 2011 revealed abuse of people with learning disabilities in institutional settings, successive governments have committed to people living in their own homes in the community. Since then, a new model has emerged in which private companies buy up properties and lease them to housing associations for the accommodation of the most vulnerable people in society.

The model hinges on the government providing Specialist Support Housing (SSH) for vulnerable people, for which it pays out high rates of housing benefit. There is no cap for how much can be charged and the Bureau has found evidence of rent for a single person reaching up to £700 per week. Investors have honed in on this opportunity and a whole market has formed.

Becks Boulter

Becks Boulter

The leases last upwards of 20 years, with built-in annual increases. This has echoes of PFI, a government procurement policy where public-sector infrastructure projects were financed by the private sector, a model that had fallen out of favour due to the spiralling costs of leases.

Civitas owns 21 per cent of supported housing in the lease-based system in England, according to information released by the Regulator of Social Housing and the company. It provides specialist housing for vulnerable people who are covered by this uncapped rent policy. It collected £45.9m in lease payments in the past year to accommodate 4,216 people across 613 properties. That means it averages at about £75,000 per property for owning the lease. The Bureau has found many other companies operating in this model, with webs of off-shore companies making the full financial picture impossible to explore.

Thangam Debbonaire, shadow housing minister and MP for Bristol West, says that some companies seem to be taking advantage of a particular loophole in the system and she is concerned that in some cases even appear to be “providing very poor accommodation at almost extortionate costs to house potentially vulnerable people”.

The revenue they bring in is considered low risk because it comes from government-backed housing benefit. Civitas Social Housing offer returns of nearly 5 per cent to shareholders, which Annabel Brodie Smith from the Association of Investment Companies described as “attractive”, especially as other companies have slashed or suspended dividends during the pandemic. There are also tax advantages arising from their structure.

Bedwardine Court, Worcestershire, is one of the properties owned by Civitas

Bedwardine Court, Worcestershire, is one of the properties owned by Civitas

According to Civitas, independent research has shown that it has saved £64.7m for local and national government per year by enabling tenants to live in the community rather than in institutions or hospitals.

But others also stand to profit from the lease-based model, and have helped it grow. There are individuals and companies that put together packages of houses and tenants by working with care providers who need to house their clients and then sell those packages to investors. Sometimes these companies also have their own housing associations, maintenance companies and care companies.

One such company is the Fairhome Group, whose chairman, John Russell, was one of the “good guy” construction experts on Channel 5’s Cowboy Builders. In 2017, the company made nearly £21.5m in profit and distributed £3.05m in dividends to its four directors and a handful of shareholders. By 2018, the dividend had grown to £8m.

The squeeze on housing associations

The Regulator of Social Housing has identified 34 housing associations that use the lease-based system. More than 260 councils in England house vulnerable people in this way, with some areas becoming dependent on the model for providing specialist supported housing. In 2015, such housing associations accommodated just 5,500 people – today it is more than 20,000. You can see the full current list – and where they operate – here.

Of the 12 leased-based housing associations the regulator has inspected in the past three years, it has issued non-compliant regulatory judgements against 11, highlighting a range of concerns, such as overly high lease payments, their management and their ability to maintain appropriate living conditions.

“We are concerned that too much money is leaving housing associations and the housing association is not left with enough to run its business effectively,” Jonathan Walters, deputy chief executive at the regulator, said. “We haven’t yet seen a housing association come forward to show how it (the system) can be made viable in the long term.”

Out of the 34 housing associations, we found that 16 charge rent double the national average for supported housing, with rents in some areas reaching three to six times the average rent charged in the region.

Traditionally, housing associations would use any revenue surplus to reinvest in existing stock. But high repayments to property investors mean that there is often not enough money left to do this under the lease-based model and the Bureau has heard concerns of how this squeeze can affect tenants. The Bureau has been told of one housing association moving people into their new homes during the pandemic, instead of seeking lease breaks from the government. A group of vulnerable young adults is said to have felt pressured to move during the crisis, despite nervousness from their families.

Civitas has boasted of its recent performance. “The company continues to perform in line with expectations and rents have been collected as normal and unaffected by Covid-19,” it said in a report earlier this year.

A spokesperson for Civitas Social Housing said: “CSH’s remit does not include the care of an individual tenant or occupation issues; our only remit is the properties themselves. CSH has never directly or indirectly engaged in any discussion regarding the suitability of move-in dates or applied any pressure on anyone, directly or indirectly, in this regard.”

There is also concern that housing associations involved in this model expanded too quickly, and accepted leases for homes that are not fit for occupancy. A consultant told us of her shock at finding a resident living in filthy conditions, while his housing association wanted the council to pay £300 per week for his home. The Bureau also spoke to families – who did not want to go on record in case it lost their children their homes – who said that properties were not fit for purpose due to damp and black mould and that complaints had fallen on deaf ears.

The Bureau has heard that some housing associations are slow to do repairs, despite rents being designed to cover intensive housing management. David Ashby is 31 and has Down’s syndrome and autism. Westmoreland housing association was leasing his home until earlier this year. Despite rent of £372 per week, his mother Helen says that she had to persistently call them for any repairs.

“It was a farce to get anything done,” she said about David’s case. “Absolutely everything required five, six, seven phone calls. We went through multiple housing managers who came and went, who would make appointments and not turn up.” She believes that the rent has been “unjustifiable” for the level of service provided.

Westmoreland didn’t comment on this specific case and has since changed its repairs contractor.

Join the Bureau Local

Become part of the Bureau Local — our collaborative network of reporters and citizens — and tell stories that matter.

Find out moreFor a housing association using the leasing model, Westmoreland charged some of the highest rents, sometimes reaching up to £700, according to the latest figures published by the Regulator of Social Housing for 2018-19. The company’s most recent published accounts for 2018 reveal that it pays 79 per cent of its rental income to property investors.

A spokesperson from Westmoreland said that the figures cited and calculated by the Bureau are from 2018 and do not reflect its current position.

Jonathan Walters, of the regulator, told the Bureau that contracts signed by housing associations often gave the perception of being more favourable to powerful third parties than to themselves. “That could be commercial naivete, doing deals they really shouldn't have done...”

“Lots of money to be made”

The Bureau spoke to the founders of Westmoreland, John and Pat Finney, who set up the enterprise in 2002 because they have a severely disabled son of their own. They prided themselves on being “people-centred”. In 2016, when they received offers of leases from industry middlemen, it seemed like a good idea. They said they believed that they would own the assets at the end of the lease agreement, which they could then use to borrow against and expand, but this soon changed into what they described as a “never-ending lease”.

In the Finneys’ view, the overall picture is reminiscent of the PFI hospital scandal. They feel that “people realised there was lots of money to be made ... That was not what we were about,” John Finney said. The couple are no longer involved in Westmoreland.

The Finneys have since started a new company called Beacon Supported Housing and David Ashby is now one of their tenants. Helen says that the service is much improved.

Councils across the country are dismayed by the high rents being asked but do not have many alternatives. “[It’s like] they've stuck their finger in the air and said, ‘How much can we get for this?’” one councillor said. The shortage of supply limits her ability to negotiate lower rents. “The motivation is to make money for private individuals off the back of these vulnerable residents,” she said, adding that high rent was not reflected in the standard of housing and service provided; most of the SSH in her area, she explained, did not offer much more than an ordinary home.

In Bristol, the council fought back against high rents being charged by lease-based housing associations, employing a team to scrutinise supported accommodation bills, negotiate with providers and send cases to appeal if they were not happy. In other parts of the country, like Greater Manchester, the lease-based system has barely made an impression, with housing associations providing this type of housing themselves.

David Ashby is much happier in his new home

Helen Ashby

David Ashby is much happier in his new home

Helen Ashby

“The pricing and quality of housing offered through this lease-based model should be better regulated,” said Thangam Debbonaire, the shadow housing minister. “People who need specialist support deserve better. Labour has proposed a 10-minute rule bill to regulate supported housing, and will be pushing the government to take it up.”

The regulator currently has limited power in this space; the coalition government removed much of its authority over property conditions and consumer standards in 2011.

While there are areas across England that have found a way to keep this type of housing and the money behind it local, the industry behind the lease-based model is only set to grow. A spokesperson from Civitas said: “CSH is a responsible social-impact investor which delivers positive social benefits alongside a financial return. CSH is proud of what it does and is confident that its bespoke, adapted properties help lead to better physical, mental, emotional and social outcomes for the vulnerable adults who live in them.”

The company plans to expand its portfolio to Northern Ireland and Scotland and also bring this model into housing for people who are homeless and leaving hospital. Michael Wrobel, the non-executive chairman of Civitas, said in a statement in June: “We look forward to continuing to support the government's policy objectives to provide community settings for people with long-term care needs.”

*Some names have been changed.

Get involved

Report the story – use our reporting recipe to dig into the issue in your area and tell the story or share an experience of your own with your local press

Join the discussion – share your take on the model using #WhoBenefits

Start a conversation in your area – raise with your councillor, head of housing or a local organising group

Header image: Creative Commons. Illustrations by Becks Boulter

Our reporting on the housing crisis is part of our Bureau Local project, which has many funders. Our work on the housing crisis was supported by the Bertha Foundation. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.