Lack of oxygen leaves patients in Africa gasping for air

As Covid-19 spreads throughout Africa, a potentially deadly lack of oxygen is leaving patients gasping for breath. Many are having to go without this essential treatment.

Some experts apportion considerable blame to the two multinational gas suppliers who dominate the market for oxygen cylinders in most African countries, saying their high prices make the treatment unaffordable.

Ex-employees, industry insiders and hospital staff have told the Bureau of Investigative Journalism that in their opinion the Linde Group and Air Liquide have overcharged for medical oxygen and on occasion limited hospitals’ supply. They perceived the Linde Group as trying to reduce competition, and making it difficult for clinics to switch to cheaper systems.

In most European and North American hospitals, oxygen is delivered by tanker and piped directly to patients’ beds. But across many countries in Africa without this infrastructure, hospitals instead rely on cylinders. Even then, oxygen is only routinely available in big hospitals in major cities. One nurse in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, said that in her hospital doctors frequently have to choose who receives oxygen and who does not, leaving an average of three patients a month to die without it.

The Linde Group refused to comment on any of the allegations but said they would “do everything possible to continue to reliably supply our customers”.

Air Liquide told the Bureau: “We have done everything we can to secure supply through the pandemic.” It added: “We are committed to making sure as many patients as possible in sub-Saharan Africa receive treatment and work with Unicef and a range of other international institutions, governments and NGOs to increase access to oxygen in the region.”

A life or death situation

Grace Anya watched her father Obiefula die. He was diagnosed with pneumonia and sent for a coronavirus test at Gbagada General Hospital in Lagos, Nigeria’s most populous city, on 12 May. Despite protestations that he had been vomiting and excreting blood, he was given medication and sent home.

Over the next two days he became so weak that he could not speak. He did not get his test result. The family took him to hospital after hospital, nine in total, only to be told that they had no oxygen, or were not admitting people over 50 years old, or could not treat people without a positive test result.

He became breathless and died at home.

Grace Anya's father, Obiefela, died at home of Covid-19-suspected pneumonia. Nine hospitals refused to admit him

Grace Anya's father, Obiefela, died at home of Covid-19-suspected pneumonia. Nine hospitals refused to admit him

Grace said it was hell to watch her father suffer

Grace said it was hell to watch her father suffer

It was hell to watch, said Anya. In her view, he would not have died if he had access to oxygen.

With still no cure for Covid-19, oxygen is a key treatment. As lungs become damaged by the virus, people suffer extremely low oxygen levels in the blood, called hypoxaemia, which can eventually be fatal. Oxygen buys time for a patient’s immune system to clear the virus.

While the majority of people with Covid-19 have mild symptoms, of all patients, 14% will need oxygen in hospital and 5% will need mechanical ventilation in intensive care. Yet, across countries including Nigeria, Kenya, Burkina Faso, Guinea, South Africa, South Sudan, Cameroon, Ethiopia and Tanzania, many hospitals and dedicated Covid-19 isolation centres have reported oxygen shortages.

In high-income countries, liquid oxygen is delivered and stored in giant containers on hospital grounds before being turned back into gas and piped to the patient’s bedside. This is much more efficient than transporting oxygen in compressed gas cylinders, as is generally done in poorer countries. As a result, oxygen in sub-Saharan Africa tends to be at least five times more expensive by volume than in Europe and North America.

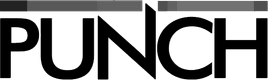

The price of a 6.8 cubic metre cylinder of oxygen (a “J” cylinder), enough to treat an adult for roughly a day, ranges from $112 in Guinea, including transport, to $23 in Kenya. (Air Liquide said that comparisons of prices between countries were “unfair” because production costs vary.) Additional costs can include a cylinder deposit fee of about $300, a monthly cylinder rental fee of about $25, and paying to transport cylinders to the gas company’s depot. As some big hospitals need up to 80 cylinders a day, the costs can quickly spiral.

Air Liquide and the Linde Group, European companies whose African subsidiaries include Afrox and British Oxygen Company (BOC), operate across nearly every country in Africa. Hospitals represent only a small part of their business; they also supply so-called industrial oxygen to the mining, chemical, welding and food industries. Globally the Linde Group and Air Liquide made revenues of $28bn and $24.5bn respectively in 2019.

Ex-employees and analysts said that some gas companies have likely made profit margins of between 45% and 88% on medical oxygen. Air Liquide has charged up to a third more for medical oxygen than industrial oxygen, even though it comes from exactly the same gas plant; BOC/Afrox has charged up to seven times more for its medical oxygen. Some ex-employees interviewed by the Bureau felt this had almost bordered on profiteering.

Air Liquide told the Bureau: “The 88% margin claim is totally inaccurate and does not reflect the economic reality of our business in Africa or the competitive nature of the market.”

Can these prices be justified? As oxygen is regulated as a pharmaceutical drug, companies have to register with the local medical authority to produce it. Thus the businesses require more stringent systems to test the oxygen for impurities and record its journey, so that it can be recalled if there is an issue.

Unlike industrial cylinders, medical cylinders are completely emptied and cleaned every time they are refilled. Some former employees say that these extra steps explain why medical oxygen costs more.

Air Liquide said medical oxygen “cannot be produced or distributed in an offhand manner. It needs to be fully traceable and of the highest quality.”

But others disagree, arguing that, in practice, this process does not significantly increase production costs, especially as most medical oxygen cylinders are returned empty.

One former gas company employee, who wanted to remain anonymous, characterised the discrepancy between the prices of medical and industrial oxygen as, in their opinion, “exploitation”.

“There’s no justification for it one way or another,” they added. “The Covid-19 crisis highlights the need for governments to treat medical gases as strategic and not be at the mercy of foreign owned suppliers.”

The price is right?

The impact of Covid-19 is just the latest symptom of a chronic shortage of oxygen across Africa.

Worldwide, pneumonia is the single largest infectious cause of death in children. In 2018, almost half a million children died of bacterial pneumonia in sub-Saharan Africa. Better access to oxygen and antibiotics could have saved many. Studies from Malawi and Nigeria show that less than a third of adults and children who needed oxygen actually got it.

In a landmark study Trevor Duke, director of the Centre for International Child Health at the University of Melbourne, found that improving access to oxygen reduced early deaths in children by 35% and says he is about to publish work suggesting an even bigger reduction in mortality.

But even when oxygen is available, it has to be paid for – along with other hospital treatments. For children with pneumonia in Nigeria, the gas accounted for half the cost of an admission, said Dr Hamish Graham, a consultant paediatrician who researched improving oxygen access. “Oxygen was a really big driving force of catastrophic health expenditure for those families.”

“These prices are completely beyond the reach of most public hospitals across sub-Saharan Africa,” Leith Greenslade, an activist from the Every Breath Counts coalition, said, “which is why the hospitals have been passing the cost on to patients.

“You can imagine how desperate that situation can be for a family, when they have just put a family member in hospital and they have had to find the oxygen to help keep them alive and come up with these huge, huge amounts of money.”

Patients that need oxygen have sometimes discharged themselves against medical advice because the costs get too high.

Air Liquide accepted that patients were charged for oxygen in Nigeria, Ghana and Cameroon, but said: “In most countries where we operate … patients are not charged for the oxygen supplied by public hospitals.”

Hospitals cannot simply shop around for a better deal if their local oxygen supply is too expensive. “There are many countries with a gas company monopoly,” Duke said. “In some countries,” he added, “the oxygen bill is the largest single drug purchase by ministries of health.”

Despite oxygen being so necessary – not only to treat pneumonia, but also in surgery, childbirth and after serious injuries – for years it was only included for anaesthesia on the WHO List of Essential Medicines, which determined the “minimum medicine needs for a basic health-care system”. It was added as a treatment for low oxygen levels in 2017.

Air Liquide and BOC have a history of pricing practices that have attracted criticism. In 2002, the European Commission fined them and five other gas companies for running a medical oxygen cartel in the Netherlands, which prompted other investigations across Europe. The companies held regular meetings to fix prices and agreed not to deal with each other’s customers for at least two months every year, which were concluded to have been in order to raise prices and keep them at the set level.

Between 2001 and 2011, Air Liquide and Praxair – which later merged with the Linde Group – were investigated for perceived cartel-like behaviour in a series of cases in Latin America. The Argentinian competition authorities fined Air Liquide, Praxair and two other companies $24.3 million in 2005 for price fixing and allocating customers. Praxair and two other companies were fined $8m in 2010 for bid-rigging in Peru.

Such investigations are not wholly consigned to the past. The Linde Group’s subsidiary Afrox is currently being investigated by the South Africa Competition Commission for concerns over alleged price-fixing over liquid petroleum gas cylinder rental schemes. Medical oxygen also uses similar cylinder schemes.

“It's quite obvious that there are structural framework conditions to encourage coordination and thereby anti-competitive practices,” Maria Teresa Da Piedade Moreira, of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, said. “It's one of those sectors where the investments to enter the market are so high that you will never have a competitive market.”

Air Liquide said: “The market for oxygen in sub-Saharan Africa is competitive, with more than 15 medical oxygen suppliers across the region.”

Exposing systemic failings through investigative journalism isn’t a quick fix. It takes time to uncover the evidence. It takes time to get people to notice. But when we take that time, we can get results. Help us do more.

Support the Bureau today

Community action

Over the years, smaller companies have tried to provide cheaper oxygen. Insiders say, however, that the multinational companies fight to maintain their market share.

The Bureau found evidence of the Linde Group trying to blunt competition. Before 2013 its Kenyan subsidiary BOC Kenya had a near monopoly and was charging about $58 per J cylinder, plus transport to the Nairobi plant, a cylinder deposit and a leasing fee on top of the refill cost.

Dr Steve Adudans and Dr Bernard Olayo, of Kenya’s Centre for Public Health and Development, acquired funding and built their own oxygen plant under the name Hewatele – “abundant air” in Swahili. The pair devised a system to drop off and pick up oxygen cylinders directly from hospitals and clinics for free, providing rural areas with oxygen for the first time.

One of Hewatele's oxygen plants

One of Hewatele's oxygen plants

A year after the doctors set up the business they were approached by a BOC Kenya representative who met them at a restaurant and asked them to shut down their plant and distribute BOC Kenya’s oxygen instead. They declined.

Instead they expanded, building two more oxygen plants. “If you're a dominant player, you probably want to protect your market share,” Olayo said. “If someone wants to take it away you better convert them or you aggressively compete against them.” Hewatele charges $25 for a J cylinder; BOC soon reduced its prices for some hospitals to compete, Olayo said.

One of Hewatele’s plants was built on the grounds of the Rift Valley General Hospital in Nakuru, Kenya’s fourth largest city. According to Dr John Murima, who was then the area’s medical superintendent, the hospital had previously suffered shortages. BOC orders, which had to be driven for 3 hours from Nairobi, often turned up short.

Switching to Hewatele meant a cheaper, steadier supply. “We were able to cut the costs of oxygen by 40%” Dr Murima said. BOC tried to tempt Rift Valley General back, offering a 5% discount for refills and other incentives, but the hospital stuck with Hewatele.

Other hospitals found it harder to switch, Olayo said. Their flow meters, valves which regulate how much oxygen is released from the cylinder, only fit BOC Kenya’s cylinders. This design is “absolutely purposeful”, a former industry insider told the Bureau. “My entire life as a young worker, that’s what we did. We created those barriers intentionally to make swap-out as difficult as possible.”

The companies also install tanks and piping when hospitals opt for liquid oxygen, the ex-employee added, and this infrastructure also stops hospitals from switching suppliers.

It is “completely wrong” that gas companies use their cylinders to seek to tie hospitals to their product, because they cannot always deliver all the oxygen a hospital needs, said Temie Giwa-Tubosun. She set up AirBank, the service she now runs as chief executive, to distribute free emergency oxygen cylinders to Nigerian hospitals, when she saw a news story about a man who died after being sent to five different hospitals, none of which had oxygen. The project is funded by corporate donations.

AirBank has to supply a full adaptor kit, worth $129, to hospitals to ensure that their cylinders can actually be used. “By tying hospitals to this one system you're actually putting people at risk,” she said.

After turning down BOC’s offer, Olayo did not hear from them directly, but heard stories of them trying to win back Hewatele’s customers. Then, in July 2019 he received a letter that accused Hewatele of illegally filling up BOC Kenya’s cylinders at their plants, an allegation he vehemently denies. “We have never filled their cylinders,” he said. His perception was that BOC was seeking to put inappropriate pressure on him.

Some hospitals report that oxygen companies have occasionally limited their oxygen supply. Usually, 35 cylinders were delivered every day to Yalgado Ouedraogo University Hospital in Burkina Faso, said Idrissa Ouedraogo, who is in charge of buying the hospital’s oxygen. But in March, Air Liquide said that the hospital could only order more cylinders if they had returned 60% of those already provided. But those cylinders were still in use.

Now only ten cylinders a day are delivered, and the hospital is constantly close to running out of oxygen. On a day when the delivery did not arrive at all, Ouedraogo said he told Air Liquide he was concerned he might have enough to last until morning, but no more arrived that day.

Air Liquide told the Bureau: “Given the unprecedented increase in demand, leaving empty cylinders in one hospital would result in a shortage elsewhere – creating an unacceptable risk to patients. No hospital ran out of the supplies they needed from us.”

A concentrated effort

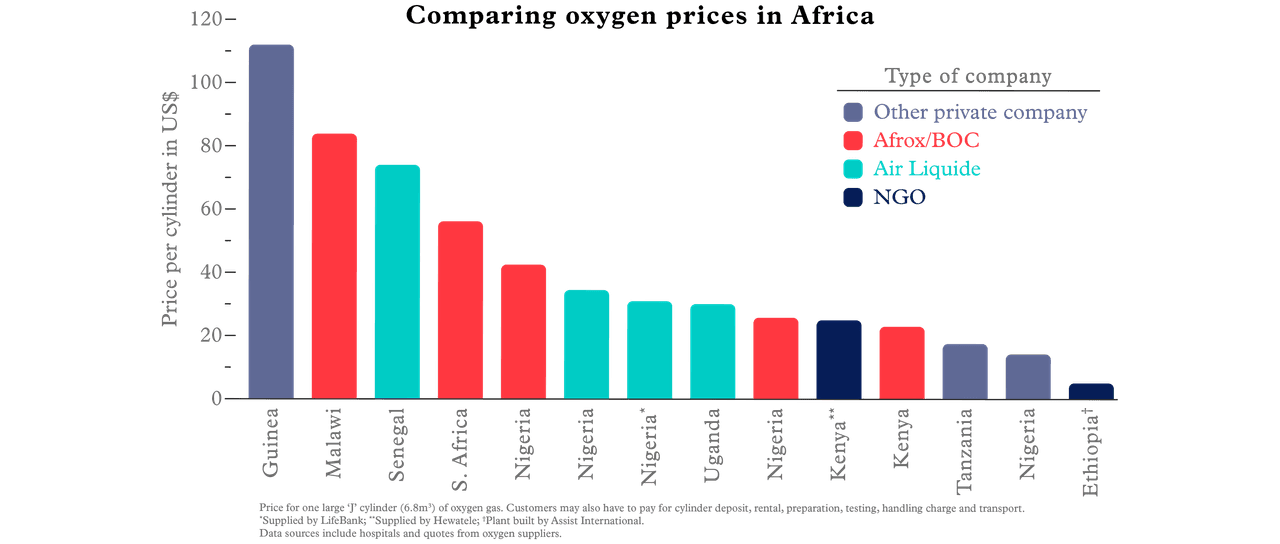

As the coronavirus crisis deepens, the World Health Organization, World Bank and Unicef are shipping thousands of oxygen concentrators to 120 countries. These portable, suitcase-sized machines convert ambient air into oxygen and can be used at a patient’s bedside in place of cylinders.

But in a meeting about acquiring concentrators for Kenya, the Kenyan Health Federation, whose oxygen division is led by BOC, appeared to have ruled out the oxygen these concentrators produce for use for Covid-19 patients, saying that only 99.95% concentrated oxygen should be used.

That concentration is only possible with oxygen made cryogenically – where air is frozen so that the oxygen and nitrogen separate and liquid oxygen is formed. This is the method used at BOC’s African plants. The other two methods to make oxygen – the concentrators and pressure swing adsorption (PSA) plants (like those built by Hewatele) – produce concentrations of between 93% and 99%.

Kate Baldwin for TBIJ

Kate Baldwin for TBIJ

Experts disputed the health federation’s reported stance. The World Health Organization defines medical oxygen as anything above 82%. There is no clinical reason to raise the WHO oxygen purity recommendations, said Dr Hamish Graham.

“There is a common misconception that 99% is ‘better’,” Graham, who has led projects to increase access to oxygen, said. He said Nigerian technicians and healthcare workers have told him that gas companies and cylinder distributors contributed to the perpetuation of this misunderstanding, claiming that cylinder oxygen is more appropriate than concentrator oxygen.

Whichever type of oxygen is supplied, the gas given to patients is mixed with air, reaching the lungs at concentrations of up to 50%.

Supplying oxygen concentrators would help hospitals to be more “independent” of gas companies and mean hospitals that are not accessible by road still had access, said Dr Hans Lang, a paediatrician working for Alima, a global health NGO. He added that oxygen production needs to be “decentralised” – produced near patients rather than at a gas plant in the country’s capital.

Alima has ordered 280 concentrators to be distributed around Guinea on top of 50 that have been sent to Donka hospital in Conakry, the capital. At present, the hospital spends between $2,800 and $9,000 a day on cylinders from Sogedi, a former Air Liquide subsidiary.

A concentrator costs about $1,000 to $2,000, but the electricity to produce one cylinder’s worth of oxygen costs less than $1.50, so the machine can soon pay for itself. The WHO and Unicef have bought more than 30,000 concentrators to send to countries that need them, although more recently the WHO warned of shortages.

Concentrators are not a perfect solution. Electricity is not always available, and stories of patients dying during blackouts are common. They were not built for hot, dusty or humid conditions, so are prone to breaking down.

Innovators have tried to find ways round these problems. Professor Roger Rasool, a physicist at the University of Melbourne, has developed concentrators that can run on solar or river power and have a “bladder” which stores oxygen and continues supplying patients when the power goes off. In a trial at Mbarara hospital in Uganda, the machines eliminated oxygen shortages and cut the number of cylinders used in three months from 77 down to two.

Grow your own

A longer-term solution for hospitals to build their own oxygen plants, either for piping the gas to patients or to fill cylinders for their own use and for other local clinics. It is an expensive project – plants can cost from $100,000 to $1.5m, with electricity and staff costs on top – but investing can mean improving oxygen access across a large area.

The Ugandan ministry of health used donations to build an oxygen plant at every regional hospital, meaning health centre staff no longer need to drive to the capital to get oxygen. “There's been great improvement,” said Sheillah Bagayana, a biomedical engineer who helped install the first plant. “Oxygen used to be a huge, huge challenge. You’d literally have no option ... just watch the patient die. Now, at least doctors don't have to decide which patient gets oxygen.”

There have been challenges: at first technicians were expected to carry out their day jobs while also running the plants. There is no night shift, so the plants run at half capacity. Power cuts shut off the supply.

“Ministries of health and governments have to realise they have to invest in health systems to save money,” Trevor Duke said. This, he added, “requires a sort of multidisciplinary effort [rather] than just signing a check to BOC every quarter”. But he argued that by most calculations the expenditure can be regained within three to five years.

“Medical oxygen is the only thing available to really keep patients who get very sick alive.”

Demand for oxygen is rising.

“In Africa, now we're in the middle of a pandemic,” Leith Greenslade said, “and medical oxygen at the moment is the only thing available to really keep patients who get very sick alive.” There have been a million recorded cases of Covid-19 across the continent, with tens of thousands of new cases every day.

The Bureau visited Kongoussi hospital in Burkina Faso in mid July. Doctors said that a six-month-old boy had just died from pneumonia because another child was connected to the only oxygen concentrator.

For this young boy, for Grace Anya’s father and for the thousands of others who have died because of oxygen shortages, any changes will come too late. But, Greenslade said, if there was ever a time for discussions and negotiations with the five or six gas companies that control most of the market, it is now.

Additional reporting by Rosa Furneaux, Nasibo Kabale

Header image: A young boy with severe pneumonia being treated with oxygen at a hospital in Kenya. Image courtesy of Save the Children.

This article is part of our Global Health project, which has a number of funders including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.