Finding the faces of Afghanistan's slaughtered civilians

Masih ur-Rahman Mubarez’s life changed in a single moment. It took eight months to find out why.

In the early hours of September 23, 2018 a bomb struck his house, killing his wife, seven children and their four teenage cousins. Both the US and Afghan militaries – the only forces carrying out air strikes in the country – denied responsibility. It took months of work by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism with The New York Times to prove the US had struck the house, and it all rested on a photograph showing a four-pronged mark in the wreckage.

For one family, the question was answered. But the Bureau has been tracking strikes in Afghanistan for more than five years. Last year the air war intensified, with record numbers of civilians killed or injured. More and more families are being left behind to search for the truth.

The TBIJ database included 21 strikes from 2019 that were devastatingly similar – all were reported to have hit buildings, and many were thought to have destroyed family homes. All deserved to be investigated. However, finding what happened to Masih’s family had taken months. Replicating this for more than twenty cases would be impossible without help from new methods and means of investigation.

The challenge

Investigating on the ground in Afghanistan is perilous and difficult. Strike sites can be in remote areas, where security is a very real concern. Even with a reporter in Kabul, contacting an affected family can often mean weeks of waiting; telephone lines are frequently damaged.

Instead, the Bureau turned to the independent investigation site Bellingcat. The organisation has built up a stellar reputation for “open source intelligence” (OSINT). OSINT investigations use satellite imagery as well as information and photos posted on social media, paying close attention to the details to get to the truth.

In the words of the site’s founder Eliot Higgins, who rose to prominence using OSINT to help track the people who brought down the MH17 plane over Ukraine: “I realised you could get a good idea of where the front lines were in Libya and who was fighting where, just by closely following information shared online.”

Bellingcat has created a community of dedicated OSINT investigators – some professional, some hobbyist, all working remotely. When it put out a call for a team of volunteers to investigate the Bureau’s list of 20 strikes, more than 150 volunteers signed up.

The weapon fragments found at the site of the strike that killed Masih's family, which led back to the US

Via Masih

The weapon fragments found at the site of the strike that killed Masih's family, which led back to the US

Via Masih

For each incident, two key questions were put to the group: Could they prove the strike took place? Could they prove it killed civilians?

If those were answered, there was a third: who was behind the strike? This question is always the hardest to answer, but one thing the project has found is this: if you can narrow down the first two, you get a better shot at the third.

Their months of digging generated huge amounts of visual evidence: photos and videos showing the rubble of houses, the bodies of alleged victims and the angry aftermath of strikes, all of which could serve as proof – at a minimum – these incidents had occurred.

Most of this came from social media. Smart phones have put the daily lives of millions of people in the public domain via platforms like Twitter, Facebook and Instagram – and social media captures the dark moments as much as the light. Across these platforms people are sharing evidence of crimes, whether they are communities documenting an injustice or perpetrators showing off their cruelty.

This has by no means made “traditional” journalism redundant – but it does create a helpful starting point. When volunteers found information through social media, it was passed to contacts with experience reporting on Afghanistan to follow up, for example by finding a family member to contact, or calling an outspoken official in the region.

This is a big part of the value this type of work can have, said Nick Waters, an investigator for Bellingcat. “It means we can do intelligence-led on the ground reporting … It means we can sit here and say if we go to this village and exactly this house, we may find what we’re looking for.”

Baghlan

July 9 2019

One of the strikes on the Bureau’s list had hit a building – a home – in Baghlan province, north of Kabul, on July 9, 2019.

Early narratives around this incident were conflicting. A few brief lines in news reports at the time said that the Afghan Ministry of Defence had admitted civilians had died in a strike, but stopped short of taking responsibility. And while the US denied carrying out strikes in the area, the governor of the province was on camera blaming Nato forces – a common shorthand for the US, the only Nato member still conducting air operations in Afghanistan.

Coordinating an OSINT operation involves setting priorities for different strikes – what is known already, and what’s most important to find out? Do we know for sure that a strike happened, or are we trying to pinpoint where and when?

In the Baghlan case, the key information to find was the coordinates. In incidents like this, where responsibility is not clear, finding the exact location of the strike can make a huge difference. In the strike on Masih’s house, it was this detail that had prompted a reversal of the US military’s initial denial.

Finding the coordinates of a single house is a difficult mission.

In this case, the village hit by the strike had been named in a Taliban video. That name could be cross-referenced with a report by Humanitarian Response to get a better understanding of its location. The group then used the video and other photos found online that showed the aftermath of the strike to identify distinctive features of the building hit that might be visible from above.

Photos posted online that were said to show the aftermath of the strike allowed the team to find key features of the compound

Photos posted online that were said to show the aftermath of the strike allowed the team to find key features of the compound

There was a compound with an L-shaped building in its northeastern corner, a small grove of trees inside that compound and a line of trees and a low line of vegetation that flanked it. The OSINT volunteers scoured for those features in the area identified on satellite maps, until one user found a strong match.

Now we had what we thought were the coordinates of the house. Looking at the building before July 9 and after on satellite imagery could prove we were correct – could we see damage consistent with an airstrike? Would there be an outline of a house in one photo, gone in the next?

There was just one snag: the week the project launched, the main provider of affordable satellite imagery announced it was withdrawing its services.

The investigation into the strike on Masih’s house was able to use satellite imagery to not only see the damage to his house, but also to see evidence of his children’s graves from above. It was a crucial piece of the puzzle.

In other cases across the country, it has not been so easy. Even spending hundreds of pounds does not guarantee good quality images, as certain areas are only available in very low resolution.

“It’s deliberately degraded,” said Waters. “Most of the aerospace industry is inextricably bound up with defence and diplomacy,” which makes it more difficult to investigate events in certain countries.

London

February 2020

The team had to press ahead without satellite images. But they had the coordinates. Or so they hoped.

The Afghan Ministry of Defence statement had also evidenced civilian harm – but who were those civilians? If accountability is to be real, it cannot just be about admitting the fact of a strike, but also its key details – most crucial of all, putting names to impersonal fatality numbers.

Finding those names began with online searches. In this case, the community was quickly able to uncover a large volume of visual evidence. Attached to a news report on the strike in Dari, one of the main languages in Afghanistan, was an image said to be from the scene. It showed the remains of four children and what looked to be another two adults, although damage to their bodies made it difficult to tell.

It is vital to check the authenticity of such images. One of the early steps is to run a reverse image search, via major English language, Russian and Chinese search engines, to check whether similar images have appeared elsewhere.

For this photo the reverse image search did turn up a match, leading to social media posts containing additional close-up images of children’s bodies. The photos from this search had not been shared before the date of the alleged attack, making it more likely they were from this incident.

Searching through imagery like this can take its toll, especially after prolonged periods of time. People working or regularly volunteering in the field have been known to eventually struggle with trauma as a result of what they’ve seen. Working in this field requires constantly striking a balance between limiting exposure while still collecting evidence.

The team had to sift through images showing the victims' bodies and graves to find clues to their identities

The team had to sift through images showing the victims' bodies and graves to find clues to their identities

And not all of that evidence may be true. Along the way to finding the answers in this case, there were possible red herrings, including a video showing fragments of weapons said to have been found in the wreckage, which appeared to be from an American bomb.

However, this section of the video had been tacked onto what appears to be a modified version of a longer video produced by the Taliban, which didn't show any fragments. The area surrounding the fragments was also not shown making it hard to verify whether it was filmed in the same location.

However, while militant sources must be treated with caution, they are still useful, according to Abdullahi Hassan, an Amnesty International researcher investigating strikes in Somalia. “When [al Shabaab] share photos or videos, it does not mean they are useless, especially for people like us struggling to get evidence related to an incident.”

In Somalia this can be the only visual evidence coming from a strike site, given that the militant group has banned mobile phones in the otherwise inaccessible territories they control.

But, as Hassan says, this makes verification all the more important. Among the pro-Taliban accounts sharing details of the Baghlan strike was a Twitter user who described himself as a lead political analyst. His profile picture showed him appearing on Afghan television. He posted a photo and wrote that the victims were all members of his family, whom he had met three months earlier.

Finding an affected family in Afghanistan can be like finding a needle in a haystack. Poor phone lines, shifting Taliban territory and rural locations all add complications. But sometimes social media can help provide that missing link.

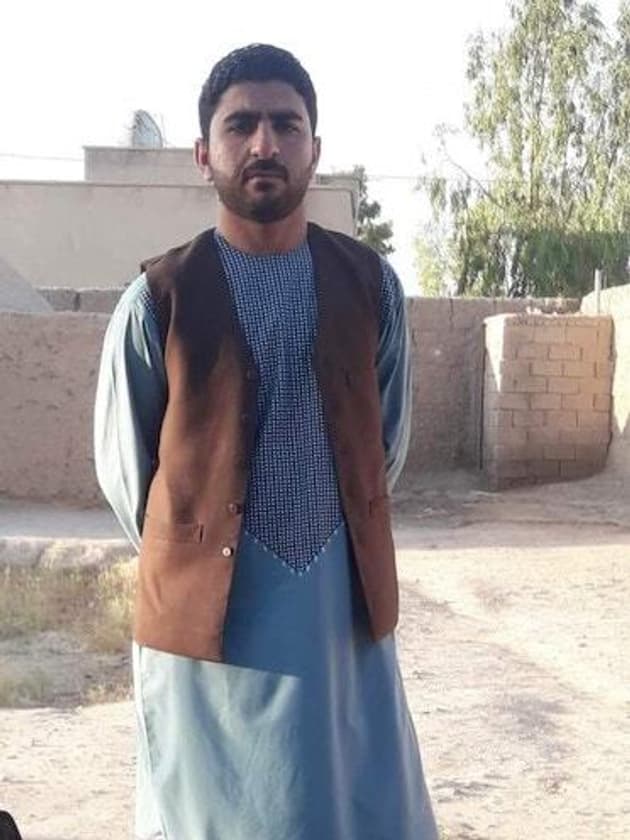

This was one of those times. Within a few days of a direct message on Twitter, this relative led the team to Ismael Khan.

On the phone, Ismael was quiet and shy, but although the call broke up several times he pressed on, calling back several times in the hope of a better signal. He spoke slowly; his speech had been affected by a head injury. He’d been hurt the night his home was bombed.

Ismael had been sleeping in the family’s terrace.

Ismael Khan

Ismael Khan

“The bombing woke me up,” he said “I wasn’t fully under the rubble and one of my hands was stuck in it.

“I wasn't very conscious but I could reach and touch one of my son's body. I knew that he was dead.”

He was taken to hospital. When he came round, he learnt that it wasn’t just his son that had died that night. His wife, Naseema, and six of his children were gone. The youngest was just two years of age.

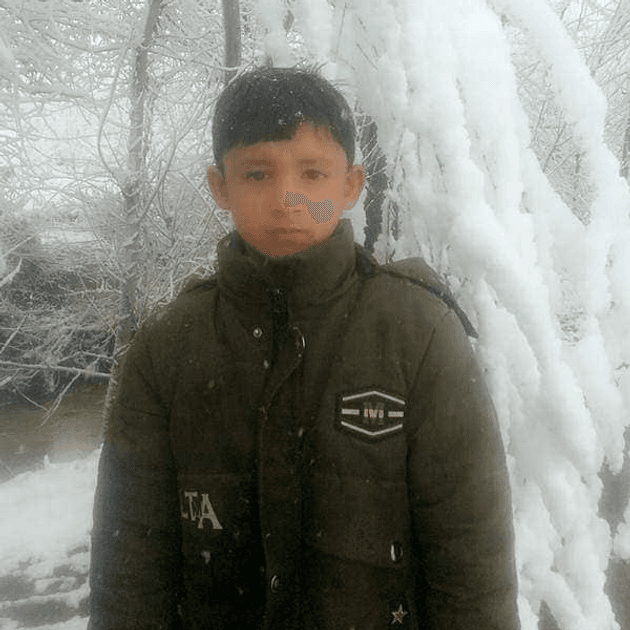

Ismael provided us with photos of his children: his sons, Khairullah, 15, Bakhtullah, 12, Shirullah, 10, and Sunaullah, the youngest at only 2, and his daughters Ruqia, 9, and Nazmeena, 7. For the first time, we saw his children as they had been before the strike - wrapped up in warm winter coats, very much alive.

Khairullah, 15

Khairullah, 15

Bakhtullah, 12

Bakhtullah, 12

Ruqia, 9, circled left, and Nazmeena, 7, circled right

Ruqia, 9, circled left, and Nazmeena, 7, circled right

Shirullah, 10

Shirullah, 10

Sunaullah, 2

Sunaullah, 2

Farah

May 24 2019

On 24 May 2019, a NGO building was allegedly hit in a strike and two charity workers killed. The incident was reduced to a few lines in a general monthly update on the violence in Afghanistan.

This case stood out, even in a dossier full of tragedy. A strike may have hit a charity and killed two staff members. What was the charity? Who were the workers?

The US military had deemed this alleged strike “possible”, a form of words meaning they had not accepted responsibility, but they had not denied it either. The military had also said the strike on Masih’s house was “possible” following the evidence published in our story. For him and others, this word can rob survivors of closure.

The admission that the allegation of civilian harm was “possible”, however, did mean that a strike had occurred – the team did not have to establish coordinates or find satellite imagery to prove it had taken place. Instead, the work narrowed down to finding out who had been killed. Like in the Baghlan case, the team needed that missing link that OSINT could provide.

It came in a eulogy for a man named Abdul Hamid Alkoazay. It was posted on Facebook on the day of the incident and underneath were tens of comments mourning his loss. Key details matched - his name tallied with another public tweet and there was mention of a plane.

More searching uncovered the alleged victim’s Facebook page. It is always eerie searching through a dead man’s social media. They seem like any number of people you only encounter online, making their death seem almost unbelievable, even when the digital trail ends abruptly.

Abdul Hamid Alkoazay

Abdul Hamid Alkoazay

With his newborn niece

With his newborn niece

The Facebook profile revealed a young man with a love of sport and a wide circle of friends. His photos showed him with friends in their graduation caps and gowns and one of him holding his newborn niece. And here among all these memories, were his coworkers, friends and family. Each was a potential connection to speak to and find out more about him, and about the day he died.

This is how we found his brother, Abdul Hadi Alkoazay, who described Abdul Hamid as kind, hard working, honest and pious. “His death is a huge loss for us,” he told us. Their mother was still deep in grief. Abdul Hamid had also been supporting the family financially as their younger brother studied at university, he added.

The OSINT team also uncovered an article that gave us a name for the charity and one of its directors – who the Bureau managed to track down via social media. It was called Coordination of Humanitarian Assistance (CHA), and had been working in Afghanistan since 1987 across health, environmental issues, education, water provision, community development and disaster and emergency response.

Haji Malik, the charity’s provincial director, confirmed Abdul Hamid’s death and gave us the name of the other man who died that night: Abdul Rahim Jan. Malik could not understand why the office had been targeted and his employees killed, saying there was no Taliban presence in the immediate vicinity.

Speaking with Malik helped the team piece together the events of that night. Abdul Hamid and Abdul Rahim had stayed the night at the charity’s office, which was not uncommon – the building served as an office, but also as a safe place to stay for staff; Taliban fighters have repeatedly targeted NGO staff. At about 1.20am, a strike hit, killing them both instantly.

Abdul Rahim was 22 and had got married a month before his death. He worked as a supervisor at the charity, which he had joined relatively recently. One colleague said of him: “He was such a softly spoken person. He was a very good man with the best manners.”

Malik claimed the local governor had told CHA the strike had been conducted by US forces - but no one from the US military had contacted the charity, and, he said, no compensation had been paid to the families.

Bagram base

March 2020

Using open-source investigation – starting with tweets and international media – created enough new leads to get closer to the truth in both cases, whether that was confirming the attack itself or finding out more about who it killed.

In fact, progress – be it big or small – was possible in all the 21 cases opened up to the online community. In some cases we were only able to uncover additional reporting or unverifiable social media posts about the strikes, but in others we were able to confirm strikes and their civilian death toll, putting names to numbers.

We took our findings to the US military press office based in Bagram airfield, Afghanistan.

The US military did not respond to any of the specific allegations the Bureau put to them. A US forces in Afghanistan spokesman said: “The global community has been very clear – the best way to protect civilians in Afghanistan and prevent civilian casualties is to stop the fighting. Reducing the violence is an absolute necessity – and this is up to the leaders of all military forces. Attacks generate attacks, while restraint produces restraint. All sides must choose restraint to prevent more killing and violence.”

He cited “a drastic increase in Taliban violence” since the agreement was signed at the end of February and added: “We call on the Taliban to live up to their commitments, reduce violence now, take part in intra-Afghan negotiations, and make real compromises for a lasting peace that benefits all Afghans.”

In its response, the US did not make any reference to civilian casualties in 2019, when all of the strikes we investigated took place.

The Afghan military did not respond to the Bureau’s questions.

However, despite the lack of official answers, there are still reasons to hope for better. Contributors from across the globe helped collect information that can be added to our database, making the picture of what happened somewhat clearer, and perhaps creating a foundation for others to carry on building upon.

“There is so much information on the internet,” says Rawan Shaif, an open source investigator. “Open source gives you accessibility to locations that are hostile, it’s using the power of people who are there.”

Shaif began employing these techniques to examine airstrikes in Yemen carried out by the Saudi-led coalition. Just by looking at freely available satellite imagery, she could see entire civilian areas obliterated by bombs.

She turned this into a more comprehensive investigation, working with Waters at Bellingcat to collect the mountains of evidence out there and preserve it.

“Part of the project was to prove a point to the government that post-strike assessments could be done using open source data,” Shaif said. “And if we could do it, they should be able to do it too.”

Abdullahi Hassan agrees that poor responses from military forces do not undermine the value of OSINT work. “I believe documenting and gathering evidence on each strike with civilian casualty allegations is extremely important,” Hassan said. “You don’t know when people will be held accountable … Justice might happen for these families one day.”

Rawan has similar hopes for Yemen. “Accountability isn’t always immediate,” she said. “I’m pro long-term preservations, long-term archiving, making sure this information exists in years to come

“You never know, one day Yemen may have a legal system that is wholesome and transparent, and one day they may pick this up and there may be local reckoning.”

Header image: Abdul Hamid Alkoazay, killed in an air strike in Farah, holding his newborn niece

Our Shadow Wars project was funded by the Open Society Foundation and the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.