Rockfire Capital: a private firm with millions of pounds of public money

A business that marketed itself as an investment opportunity for local authorities has used taxpayers’ money to propel itself to the fore in the UK’s solar energy market, despite concerns over the extent of the security of these kinds of investments by councils.

Council records reveal that Thurrock has made payments of at least £74m, and possibly far more, to Rockfire Capital, an investment firm which helped to raise £432m from councils that was used to buy 56 solar farms across the UK between late 2016 and the end of the following year.

Other councils, such as the London boroughs of Havering, Newham and Bexley also invested in this bond scheme, but Thurrock appears to be the single local authority largest backer. Its exposure alone could run into hundreds of millions of pounds.

Thurrock’s investments reflect the build-up of debt by local authorities since the financial crisis, as spending cuts forced councils to look for ways to supplement their income. Over the past three years, an unelected council official has signed off loans from about 150 local authorities and council pension schemes. Sean Clark, Thurrock’s corporate director of finance, governance and property, then invested £702m of that cash in renewable energy deals. It is a substantial bet. Thurrock’s £1bn borrowing spree accounts for more than 10 per cent of all short-term inter-local authority borrowing in the UK. It dwarfs the council’s annual budget, which stood last year at just £220m, according to data from the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government.

Mr Clark and the Conservative-controlled council have refused to say precisely where the money has been invested. They argue this would harm Thurrock’s commercial interests and “would result in other companies offering similar investments not wanting to work with the council”. But research by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism with the Financial Times shows that many of the investments have been into solar power schemes linked to Liam Kavanagh, an investment adviser and founder of Rockfire Capital.

News of Thurrock’s vast portfolio comes as public concern grows over the strategies councils have deployed. In parliament, the public accounts committee last month launched an inquiry into these commercial property plays. Some small local authorities have placed big bets using subsidised loans that are available from the Public Works Loan Board. This is a body attached to the Treasury that funds councils’ infrastructure spending. They include Spelthorne in Surrey, which by 2018 had assembled a £1bn commercial property portfolio, dwarfing its annual budget of just £22m. With demand for office property falling sharply as a result of the coronavirus outbreak, the Treasury is poised to ban councils from property investments including long-term assets held for yield.

Warrington's endorsement of Rockfire on the company's website

Warrington's endorsement of Rockfire on the company's website

After the Bureau contacted Rockfire, the website was taken down for redevelopment

After the Bureau contacted Rockfire, the website was taken down for redevelopment

The ‘solar bond' market

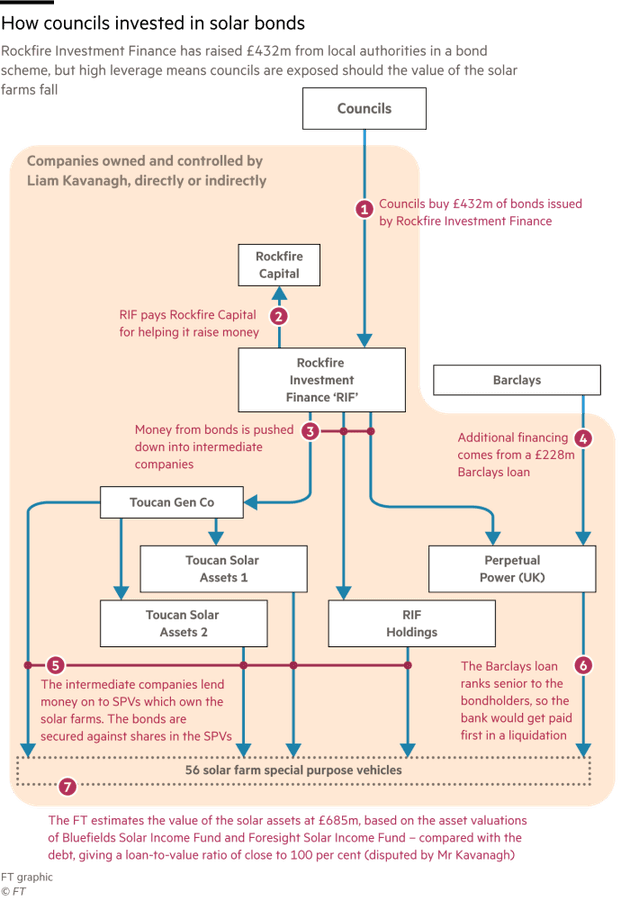

The Financial Times and TBIJ have sought to unravel the mystery of Thurrock’s giant green portfolio, of which no less than £604m has gone into solar investments. Council records show payments of at least £74m, and possibly substantially more, to Rockfire Capital Bonds Ltd, a firm whose sister company, Rockfire Capital, helped to raise £432m from councils that was used to buy 56 solar farms across the UK between late 2016 and the end of the following year. Other councils, such as the London boroughs of Havering, Newham and Bexley, also invested, but Thurrock appears to be the largest local authority investor. Established in 2009, Rockfire Capital has in recent years focused on renewable energy, advising a related financial company, Rockfire Investment Finance (RIF), on the sale of solar bonds, whose proceeds are then lent to intermediate companies that use the cash to buy solar developments.

Although Rockfire rejects the idea that these businesses constitute a group, the various entities share one thing in common: they are all controlled by Rockfire Capital’s founder, Liam Kavanagh. The energy venture has proved very lucrative for the Southampton-based investment adviser. Since his first council deal four years ago, Mr Kavanagh, 42, has banked dividends worth almost £8m. There are, however, questions over the prudence of Thurrock’s strategy. Its exposures to RIF’s bonds are not only substantial but are understood to run until 2027 and 2028. Yet much of the borrowing that supports these investments is short term. A peer review of the council’s finances by the Local Government Association in late 2018 warned of “concerns regarding the scale and leverage of investments”. It asked the council to “carefully consider whether the risks associated with your investment strategy are fully recognised and are as well managed as they could be”.

FT graphic

FT graphic

How to fund a solar farm

Thurrock’s bets on renewables reflect a wider strategy it describes as “unashamedly pro-revenue growth”. They help generate profits by exploiting the so-called “carry” between its low funding costs and the return on commercial investments; an approach that generated a net income overall of £19.2m in 2018/19, according to Mr Clark.

The council’s green adventure started in 2016 when investment brokers retained by Warrington council introduced its officials to Rockfire.

The Cheshire council had already invested £17m in five solar farm bonds promoted by Rockfire Capital and issued by RIF when its brokers, RP Martin, told Thurrock about the chance to invest in a large solar park near Swindon, 120 miles away. (Warrington has since redeemed its bonds to make a direct investment of £62m in two large solar parks in Yorkshire.)

Mr Kavanagh’s business was in some ways an unusual counterparty for Thurrock. It was neither long-established nor a renewable energy specialist. As late as 2014, it had revenues of barely £1m. RIF is not a conventional solar fund. Investors buy so-called debentures in the entity, which then lends on the cash to a string of intermediate companies, all owned by Mr Kavanagh, which purchase the solar farms. These special purpose vehicles provide the return by paying interest back up the chain. One feature of this solar business is how insubstantial Mr Kavanagh’s own capital contribution seems to be. His main companies — Rockfire Capital and RIF — have only £200,000 in paid up capital between them, and most of the others have just nominal equity.

Make change possible

Investigative journalism is vital for democracy. Help us to expose injustice and spark change

Click here to support usMeanwhile the solar portfolio itself has substantial borrowings. On top of the £432m from councils, the various corporate entities have also borrowed £228m from Barclays, giving a total of £660m. The Barclays loan is to Mr Kavanagh’s largest intermediate company, Perpetual Power UK Ltd, which owns 32 solar farms. It ranks senior to the RIF bondholders, meaning the bank would get paid first in a liquidation. Funds such as Bluefield Solar Income, a quoted vehicle that owns UK solar farms with a capacity of 465 megawatts (MW), assigned a fair value of £1.3m per MW to its assets at the end of last year. A similar fund called Foresight operating mainly in the UK, but with some farms in Australia, used a similar figure as at June 2019.

Using those as comparators, which Mr Kavanagh believes to be inappropriate, his 527MW portfolio would be worth £685m. That would suggest the total debt of £660m owed by Mr Kavanagh’s various corporate entities represents a loan-to-value ratio of about 96 per cent. The Bluefields fund has an LTV of 31 per cent. Although solar farms commissioned before March 2017 do enjoy subsidy support from the government for 20 years after commissioning, roughly 50 per cent of their income is exposed to price risk (though this can be reduced by signing long-term power purchase agreements with customers). Bondholders, and hence taxpayers, are therefore taking on a significant degree of equity risk.

Power prices can be volatile, as the coronavirus pandemic has demonstrated. Wholesale prices have nearly halved from £48/MWh last year to £25/MWh now, according to research from Cornwall Insight, although the fall has been mitigated by good weather, which has increased the output from solar farms. Yet this is not an equity risk for which RIF bondholders are well rewarded. According to the accounts of RIF, in 2018 the company paid interest of £17.7m to the holders of its £432m of debentures. That is an interest rate of just 4.1 per cent, although it is understood that bondholders may receive some form of equity return if the value rises. According to solar experts, equity investors in such ventures would normally expect a dividend yield of between about 5 and 8 per cent, plus any capital upside.

Mr Kavanagh contests any such comparison, saying RIF’s “bond structure is entirely different to that of a solar fund, and any associated valuation method or possible dividend or return for an investor is a completely false comparable”. He says RIF “has always paid bond interest in full and on time and repaid capital under the terms of each bond when required”, adding that “the structure of each bond is transparent and investors are protected by the security provided”. “Investors negotiate their own rates of return, which are competitive and, in the investors’ view, with the benefit of independent investment and legal advice, represents prudent financial management.”

As for the impact of Covid-19 on solar demand, Mr Kavanagh is sanguine. He argues the short-term impact will be “negligible” because “approximately 70 per cent” of the revenues generated by the portfolio are “fixed looking forward”. Thurrock’s 2016 Swindon deal was the beginning of a close relationship between its officials and Mr Kavanagh’s business.

The investment was revealed to councillors only some months later. “It was signed off by officers with no reference to members whatsoever,” says John Kent, a Labour member who was still leader of the council at the time. The council blamed a “period of commercial sensitivity”. In October 2017, Thurrock says the strategy received “full cross-party approval at Full Council”, since when there has been regular oversight “through both the Corporate Overview and Scrutiny Committee, which meets regularly, and the Council Spending Review”.

Questions over scrutiny

However, there remain questions over the level of independent scrutiny. Councils employ treasury advisers to provide guidance on borrowing and investments. In Thurrock’s case, this was Arlingclose, one of the two leaders in the field. Yet the council says it did not consult Arlingclose on the renewable deals. “When we did this our due diligence wasn’t through our treasury advisers,” Mr Clark says. “It was more through professional organisations like some of the big accounting firms, some of the big legal firms and valuation type firms.” Arlingclose ceased to be Thurrock’s treasury adviser in March last year and has not been replaced, an event Mr Clark attributes to “differences of opinion”. Arlingclose declined to comment.

Out of the £432m of bonds RIF had outstanding at the end of 2018, the FT understands that there are only four holders: Thurrock, Havering, Bexley and Newham. According to the latter three councils, they have a combined exposure of £11m. That potentially leaves the remainder, understood to mature in 2027 or 2028, in the hands of Thurrock alone. Thurrock has borrowed widely, regularly rolling over its loans from those authorities. Lenders include the Greater London Authority, Cornwall and Leicester councils. These appear sanguine, perhaps reflecting the fact that no council has ever defaulted on a loan and a prevailing belief that, if one did, the UK government would step in.

Thurrock’s cabinet member for finance, Shane Hebb, trumpets the investment strategy. “There are few councils that can say they have increased their general reserve by nearly 40 per cent, put £1m towards new police officers, £670,000 to tackle antisocial behaviour and £1.5m into visible environmental improvements over and above the traditional level of services,” he says, adding that its council tax remains “one of the lowest of all unitary authorities in the country”. But this has come at the cost of rapidly escalating debt. In March 2016, the council’s borrowings stood at £355m. By March 2019, they were £1.2bn. And the council’s 2019/20 Capital Strategy Report shows it could rise by a further £826m to £2.2bn by 2023.

Under reforms introduced in 2004, councils were able to borrow more, subject to local accountability. The revised prudential framework frowned on borrowing for financial investments. “If local authorities take on substantial debts to make commercial investments with the aim of supplementing their ordinary revenues, there are two big concerns,” says Don Peebles, head of policy at Cipfa, the public accountancy body. “One is that this debt has to be repaid irrespective of whether those investments perform, and second there is the concern that council services will become dependent on commercial income.” Few councils have exploited the carry trade as aggressively as Thurrock. Should those assets not perform, this could leave its residents with a headache.

Join the Bureau Local

Become part of the Bureau Local — our collaborative network of reporters and citizens — and tell stories that matter.

Find out more