Monitoring being pitched to fight Covid-19 was tested on refugees

The pandemic has given a boost to controversial data-driven initiatives to track population movements

In Italy, social media monitoring companies have been scouring Instagram to see who's breaking the nationwide lockdown. In Israel, the government has made plans to “sift through geolocation data” collected by the Shin Bet intelligence agency and text people who have been in contact with an infected person. And in the UK, the government has asked mobile operators to share phone users’ aggregate location data to “help to predict broadly how the virus might move”.

These efforts are just the most visible tip of a rapidly evolving industry combining the exploitation of data from the internet and mobile phones and the increasing number of sensors embedded on Earth and in space. Data scientists are intrigued by the new possibilities for behavioural prediction that such data offers. But they are also coming to terms with the complexity of actually using these data sets, and the ethical and practical problems that lurk within them.

In the wake of the refugee crisis of 2015, tech companies and research consortiums pushed to develop projects using new data sources to predict movements of migrants into Europe. These ranged from broad efforts to extract intelligence from public social media profiles by hand, to more complex automated manipulation of big data sets through image recognition and machine learning. Two recent efforts have just been shut down, however, and others are yet to produce operational results.

While IT companies and some areas of the humanitarian sector have applauded new possibilities, critics cite human rights concerns, or point to limitations in what such technological solutions can actually achieve.

A ship working with the EU border agency Frontex patrolling off the coast of Lesbos, Greece, intercepts a dinghy

Getty Images

A ship working with the EU border agency Frontex patrolling off the coast of Lesbos, Greece, intercepts a dinghy

Getty Images

In September last year Frontex, the European border security agency, published a tender for “social media analysis services concerning irregular migration trends and forecasts”. The agency was offering the winning bidder up to €400,000 for “improved risk analysis regarding future irregular migratory movements” and support of Frontex’s anti-immigration operations.

Frontex “wants to embrace” opportunities arising from the rapid growth of social media platforms, a contracting document outlined. The border agency believes that social media interactions drastically change the way people plan their routes, and thus examining would-be migrants’ online behaviour could help it get ahead of the curve, since these interactions typically occur “well before persons reach the external borders of the EU”.

Frontex asked bidders to develop lists of key words that could be mined from platforms like Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube. The winning company would produce a monthly report containing “predictive intelligence ... of irregular flows”.

Early this year, however, Frontex cancelled the opportunity. It followed swiftly on from another shutdown; Frontex's sister agency, the European Asylum Support Office (EASO), had fallen foul of the European data protection watchdog, the EDPS, for searching social media content from would-be migrants.

The EASO had been using the data to flag “shifts in asylum and migration routes, smuggling offers and the discourse among social media community users on key issues – flights, human trafficking and asylum systems/processes”. The search covered a broad range of languages, including Arabic, Pashto, Dari, Urdu, Tigrinya, Amharic, Edo, Pidgin English, Russian, Kurmanji Kurdish, Hausa and French.

Although the EASO’s mission, as its name suggests, is centred around support for the asylum system, its reports were widely circulated, including to organisations that attempt to limit illegal immigration – Europol, Interpol, member states and Frontex itself.

In shutting down the EASO’s social media monitoring project, the watchdog cited numerous concerns about process, the impact on fundamental rights and the lack of a legal basis for the work.

“This processing operation concerns a vast number of social media users,” the EDPS pointed out. Because EASO's reports are read by border security forces, there was a significant risk that data shared by asylum seekers to help others travel safely to Europe could instead be unfairly used against them without their knowledge.

Social media monitoring “poses high risks to individuals’ rights and freedoms,” the regulator concluded in an assessment it delivered last November. “It involves the use of personal data in a way that goes beyond their initial purpose, their initial context of publication and in ways that individuals could not reasonably anticipate. This may have a chilling effect on people’s ability and willingness to express themselves and form relationships freely.”

A phone is a vital tool for a refugee - as is communication about safe routes to take

Getty Images

A phone is a vital tool for a refugee - as is communication about safe routes to take

Getty Images

EASO told the Bureau that the ban had “negative consequences” on “the ability of EU member states to adapt the preparedness, and increase the effectiveness, of their asylum systems” and also noted a “potential harmful impact on the safety of migrants and asylum seekers”.

Frontex said that its social media analysis tender was cancelled after new European border regulations came into force, but added that it was considering modifying the tender in response to these rules.

The two shutdowns represented a stumbling block for efforts to track population movements via new technologies and sources of data. But the public health crisis precipitated by the Covid-19 virus has brought such efforts abruptly to wider attention. In doing so it has cast a spotlight on a complex knot of issues. What information is personal, and legally protected? How does that protection work? What do concepts like anonymisation, privacy and consent mean in an age of big data?

The shape of things to come

International humanitarian organisations have long been interested in whether they can use nontraditional data sources to help plan disaster responses. As they often operate in inaccessible regions with little available or accurate official data about population sizes and movements, they can benefit from using new big data sources to estimate how many people are moving where. In particular, as well as using social media, recent efforts have sought to combine insights from mobile phones – a vital possession for a refugee or disaster survivor – with images generated by “Earth observation” satellites.

“Mobiles, satellites and social media are the holy trinity of movement prediction,” said Linnet Taylor, professor at the Tilburg Institute for Law, Technology and Society in the Netherlands, who has been studying the privacy implications of such new data sources. “It's the shape of things to come.”

As the devastating impact of the Syrian civil war worsened in 2015, Europe saw itself in crisis. Refugee movements dominated the headlines and while some countries, notably Germany, opened up to more arrivals than usual, others shut down. European agencies and tech companies started to team up with a new offering: a migration hotspot predictor.

Controversially, they were importing a concept drawn from distant catastrophe zones into decision-making on what should happen within the borders of the EU.

“Here’s the heart of the matter,” said Nathaniel Raymond, a lecturer at the Yale Jackson Institute for Global Affairs who focuses on the security implications of information communication technologies for vulnerable populations. “In ungoverned frontier cases [European data protection law] doesn’t apply. Use of these technologies might be ethically safer there, and in any case it’s the only thing that is available. When you enter governed space, data volume and ease of manipulation go up. Putting this technology to work in the EU is a total inversion.”

Justin Ginnetti, head of data and analysis at the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre in Switzerland, made a similar point. His organisation monitors movements to help humanitarian groups provide food, shelter and aid to those forced from their homes, but he casts a skeptical eye on governments using the same technology in the context of migration.

“Many governments – within the EU and elsewhere – are very interested in these technologies, for reasons that are not the same as ours,” he told the Bureau. He called such technologies “a nuclear fly swatter,” adding: “The key question is: What problem are you really trying to solve with it? For many governments, it’s not preparing to ‘better respond to inflow of people’ – it’s raising red flags, to identify those en route and prevent them from arriving.”

Eye in the sky

A key player in marketing this concept was the European Space Agency (ESA) – an organisation based in Paris, with a major spaceport in French Guiana. The ESA’s pitch was to combine its space assets with other people’s data. “Could you be leveraging space technology and data for the benefit of life on Earth?” a recent presentation from the organisation on “disruptive smart technologies” asked. “We’ll work together to make your idea commercially viable.”

By 2016, technologists at the ESA had spotted an opportunity. “Europe is being confronted with the most significant influxes of migrants and refugees in its history,” a presentation for their Advanced Research in Telecommunications Systems Programme stated. “One burning issue is the lack of timely information on migration trends, flows and rates. Big data applications have been recognised as a potentially powerful tool.” It decided to assess how it could harness such data.

The ESA reached out to various European agencies, including EASO and Frontex, to offer a stake in what it called “big data applications to boost preparedness and response to migration”. The space agency would fund initial feasibility stages, but wanted any operational work to be jointly funded.

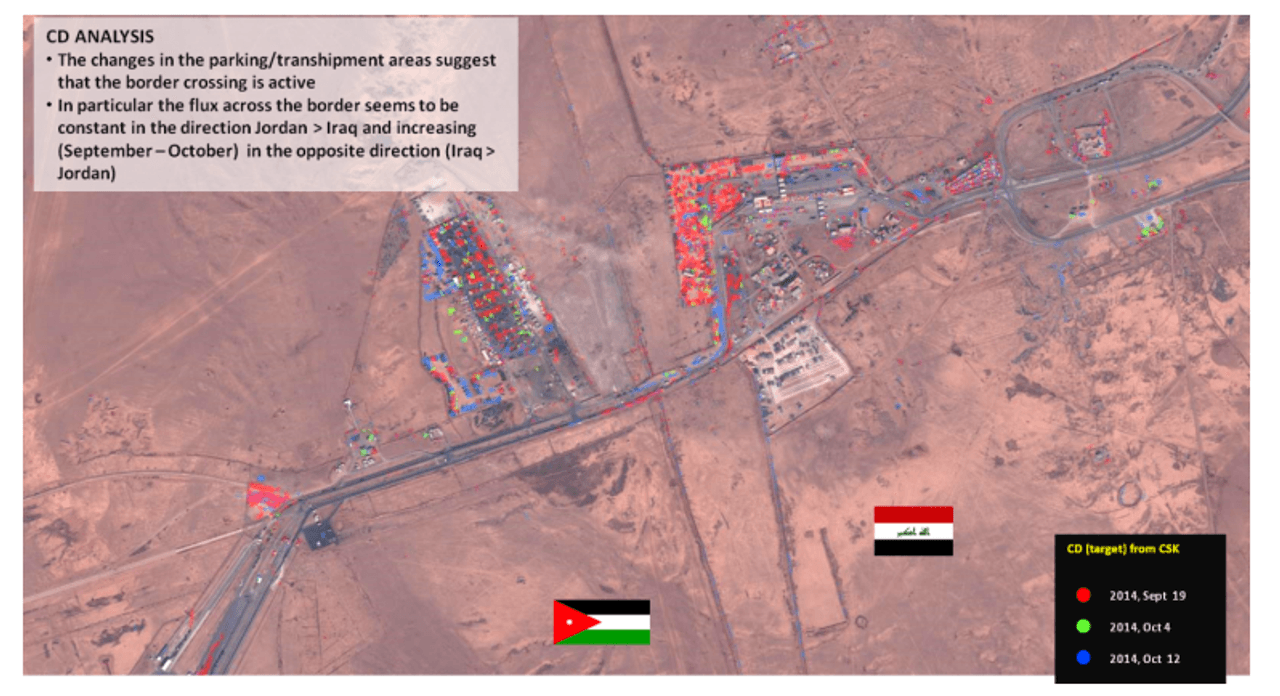

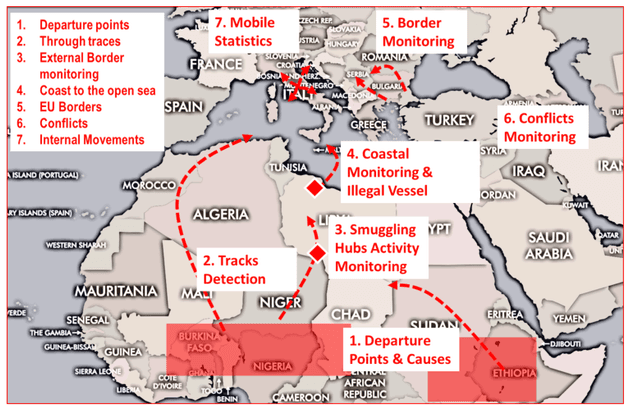

A mock up from an ESA study into the potential applications of migration tracking services

A mock up from an ESA study into the potential applications of migration tracking services

One such feasibility study was carried out by GMV, a privately owned tech group covering banking, defence, health, telecommunications and satellites. GMV announced in a press release in August 2017 that the study would “assess the added value of big data solutions in the migration sector, namely the reduction of safety risks for migrants, the enhancement of border controls, as well as prevention and response to security issues related with unexpected migration movements”. It would do this by integrating “multiple space assets” with other sources including mobile phones and social media.

When contacted by the Bureau, a spokeswoman from GMV said that, contrary to the press release, “nothing in the feasibility study related to the enhancement of border controls”.

In the same year, the technology multinational CGI teamed up with the Dutch Statistics Office to explore similar questions. They started by looking at data around asylum flows from Syria and at how satellite images and social media could indicate changes in migration patterns in Niger, a key route into Europe. Following this experiment, they approached EASO in October 2017. CGI’s presentation of the work noted that at the time EASO was looking for a social media analysis tool that could monitor Facebook groups, predict arrivals of migrants at EU borders, and determine the number of “hotspots” and migrant shelters. CGI pitched a combined project, co-funded by the ESA, to start in 2019 and expand to serve more organisations in 2020.

The idea was called Migration Radar 2.0. The ESA wrote that “analysing social media data allows for better understanding of the behaviour and sentiments of crowds at a particular geographic location and a specific moment in time, which can be indicators of possible migration movements in the immediate future”. Combined with continuous monitoring from space, the result would be an “early warning system” that offered potential future movements and routes, “as well as information about the composition of people in terms of origin, age, gender”.

Internal notes released by EASO to the Bureau show the sheer range of companies trying to get a slice of the action. The agency had considered offers of services not only from the ESA, GMV, the Dutch Statistics Office and CGI, but also from BIP, a consulting firm, the aerospace group Thales Alenia, the geoinformation specialist EGEOS and Vodafone.

Some of the pitches were better received than others. An EASO analyst who took notes on the various proposals remarked that “most oversell a bit”. They went on: “Some claimed they could trace GSM [ie mobile networks] but then clarified they could do it for Venezuelans only, and maybe one or two countries in Africa.” Financial implications were not always clearly provided. On the other hand, the official noted, the ESA and its consortium would pay 80% of costs and “we can get collaboration on something we plan to do anyway”.

The features on offer included automatic alerts, a social media timeline, sentiment analysis, “animated bubbles with asylum applications from countries of origin over time”, the detection and monitoring of smuggling sites, hotspot maps, change detection and border monitoring.

The document notes a group of services available from Vodafone, for example, in the context of a proposed project to monitor asylum centres in Italy. The proposal was to identify “hotspot activities”, using phone data to group individuals either by nationality or “according to where they spend the night”, and also to test if their movements into the country from abroad could be back-tracked. A tentative estimate for the cost of a pilot project, spread over four municipalities, came to €250,000 – of which an unspecified amount was for “regulatory (privacy) issues”.

Some pitches suggested tracking hotspots, and grouping individuals together based on “where they spend the night”

Getty Images

Some pitches suggested tracking hotspots, and grouping individuals together based on “where they spend the night”

Getty Images

Stumbling blocks

Elsewhere, efforts to harness social media data for similar purposes were proving problematic. A September 2017 UN study tried to establish whether analysing social media posts, specifically on Twitter, “could provide insights into ... altered routes, or the conversations PoC [“persons of concern”] are having with service providers, including smugglers”. The hypothesis was that this could “better inform the orientation of resource allocations, and advocacy efforts” - but the study was unable to conclude either way, after failing to identify enough relevant data on Twitter.

The ESA pressed ahead, with four feasibility studies concluding in 2018 and 2019. The Migration Radar project produced a dashboard that showcased the use of satellite imagery for automatically detecting changes in temporary settlement, as well as tools to analyse sentiment on social media. The prototype received positive reviews, its backers wrote, encouraging them to keep developing the product.

CGI was effusive about the predictive power of its technology, which could automatically detect “groups of people, traces of trucks at unexpected places, tent camps, waste heaps and boats” while offering insight into “the sentiments of migrants at certain moments” and “information that is shared about routes and motives for taking certain routes”. Armed with this data, the company argued that it could create a service which could predict the possible outcomes of migration movements before they happened.

The ESA's other “big data applications” study had identified a demand among EU agencies and other potential customers for predictive analyses to ensure “preparedness” and alert systems for migration events. A package of services was proposed, using data drawn from social media and satellites.

Both projects were slated to evolve into a second, operational phase. But this seems to have never become reality. CGI told the Bureau that “since the completion of the [Migration Radar] project, we have not carried out any extra activities in this domain”.

The ESA told the Bureau that its studies had “confirmed the usefulness” of combining space technology and big data for monitoring migration movements. The agency added that its corporate partners were working on follow-on projects despite “internal delays”.

EASO itself told the Bureau that it “took a decision not to get involved” in the various proposals it had received.

But even as these efforts slowed, others have been pursuing similar goals. The European Commission’s Knowledge Centre on Migration and Demography has proposed a “Big Data for Migration Alliance” to address data access, security and ethics concerns. A new partnership between the ESA and GMV – “Bigmig" – aims to support “migration management and prevention” through a combination of satellite observation and machine-learning techniques (the company emphasised to the Bureau that its focus was humanitarian). And a consortium of universities and private sector partners – GMV among them – has just launched a €3 million EU-funded project, named Hummingbird, to improve predictions of migration patterns, including through analysing phone call records, satellite imagery and social media.

At a conference in Berlin in October 2019, dozens of specialists from academia, government and the humanitarian sector debated the use of these new technologies for “forecasting human mobility in contexts of crises”. Their conclusions raised numerous red flags. They found a “striking absence” of agreed upon core principles. It was hard to balance the potential good with ethical concerns, because the most useful data tended to be more specific, leading to greater risks of misuse and even, in the worst case scenario, weaponisation of the data. Partnerships with corporations introduced transparency complications. Communication of predictive findings to decision makers, and particularly the “miscommunication of the scope and limitations associated with such findings”, was identified as a particular problem.

The full consequences of relying on artificial intelligence and “employing large scale, automated, and combined analysis of datasets of different sources” to predict movements in a crisis could not be foreseen, the workshop report concluded. “Humanitarian and political actors who base their decisions on such analytics must therefore carefully reflect on the potential risks.”

A fresh crisis

Until recently, discussion of such risks remained mostly confined to scientific papers and NGO workshops. The Covid-19 pandemic has brought it crashing into the mainstream.

Some see critical advantages to using call data records to trace movements and map the spread of the virus. “Using our mobile technology, we have the potential to build models that help to predict broadly how the virus might move,” an O2 spokesperson said in March. But others believe that it is too late for this to be useful. The UK's chief scientific officer, Patrick Vallance, told a press conference in March that using this type of data “would have been a good idea in January”.

Like the 2015 refugee crisis, the global emergency offers an opportunity for industry to get ahead of the curve with innovative uses of big data. At a summit in Downing Street on 11 March, Dominic Cummings asked tech firms “what [they] could bring to the table” to help the fight against Covid-19.

Human rights advocates worry about the longer term effects of such efforts, however. “Right now, we’re seeing states around the world roll out powerful new surveillance measures and strike up hasty partnerships with tech companies,” Anna Bacciarelli, a technology researcher at Amnesty International, told the Bureau. “While states must act to protect people in this pandemic, it is vital that we ensure that invasive surveillance measures do not become normalised and permanent, beyond their emergency status.”

More creative methods of surveillance and prediction are not necessarily answering the right question, others warn.

“The single largest determinant of Covid-19 mortality is healthcare system capacity,” said Sean McDonald, a senior fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation, who studied the use of phone data in the west African Ebola outbreak of 2014-5. “But governments are focusing on the pandemic as a problem of people management rather than a problem of building response capacity. More broadly, there is nowhere near enough proof that the science or math underlying the technologies being deployed meaningfully contribute to controlling the virus at all.”

Much has been made of contact tracing apps using phone record data to alert people when they may have been in contact with the disease

Getty Images

Much has been made of contact tracing apps using phone record data to alert people when they may have been in contact with the disease

Getty Images

Legally, this type of data processing raises complicated questions. While European data protection law - the GDPR - generally prohibits processing of "special categories of personal data", including ethnicity, beliefs, sexual orientation, biometrics and health, it allows such processing in a number of instances (among them public health emergencies). In the case of refugee movement prediction, there are signs that the law is cracking at the seams.

Under GDPR, researchers are supposed to make “impact assessments” of how their data processing can affect fundamental rights. If they find potential for concern they should consult their national information commissioner. There is no simple way to know whether such assessments have been produced, however, or whether they were thoroughly carried out.

Researchers engaged with crunching mobile phone data point to anonymisation and aggregation as effective tools for ensuring privacy is maintained. But the solution is not straightforward, either technically or legally.

“If telcos are using individual call records or location data to provide intel on the whereabouts, movements or activities of migrants and refugees, they still need a legal basis to use that data for that purpose in the first place – even if the final intelligence report itself does not contain any personal data,” said Ben Hayes, director of AWO, a data rights law firm and consultancy. “The more likely it is that the people concerned may be identified or affected, the more serious this matter becomes.”

More broadly, experts worry that, faced with the potential of big data technology to illuminate movements of groups of people, the law’s provisions on privacy begin to seem outdated.

“We’re paying more attention now to privacy under its traditional definition,” Nathaniel Raymond said. “But privacy is not the same as group legibility.” Simply put, while issues around the sensitivity of personal data can be obvious, the combinations of seemingly unrelated data that offer insights about what small groups of people are doing can be hard to foresee, and hard to mitigate. Raymond argues that the concept of privacy as enshrined in the newly minted data protection law is anachronistic. As he puts it, “GDPR is already dead, stuffed and mounted. We’re increasing vulnerability under the colour of law.”

Header image: The Mediterranean seen from the ISS. Credit: Tim Peake/ESA/NASA