Drug shortages put worst-hit Covid-19 patients at risk

Countries around the world are scrambling to source more ventilators for patients infected with coronavirus, but doctors fear that these will be useless without essential drugs to keep patients comfortable, the Bureau of Investigative Journalism can reveal. These drugs, which include sedatives and painkillers, are already running low in the hospital pharmacies of many countries, including the US.

“This is the most stressed I’ve been,” said Amy*, a clinical pharmacist at a hospital in New York State. Her facility is treating a growing number of patients so ill with coronavirus that they need to be connected to a ventilator to help them breathe. But the hospital is running out of the drugs for sedation and pain relief that such patients need.

In comparison to all of February, just one week in March saw the use of 10 midazolam drips, (compared to none), twice as much propofol and more than three times as much dexmedetomidine as well as 17 morphine drips, which would usually only be used for palliative care.

Amy now spends most of her day trying to order more supplies, making inventories of the medication already in stock and coming up with strategies for how to conserve it.

The problem is not confined to New York, or even the US. Hospitals around the world are facing shortages of the critical medicines needed to ventilate patients.

As a result, some doctors are having to use unfamiliar alternative drugs. Others are forced to choose drugs with greater side effects, including those that can increase the length of time a patient stays on a ventilator. In some cases, doctors are even performing potentially avoidable surgeries to take people off ventilators early, because they need to conserve medication.

As global demand for essential drugs skyrockets, there are fears that manufacturers may not be able to make enough to keep up. The pandemic has brought home just how fragile the world’s supply chain of medicines is.

Essential drugs

Most people with Covid-19 suffer mild symptoms. Some, however, develop a more severe form of the disease, and require mechanical ventilation in intensive care to help them breathe.

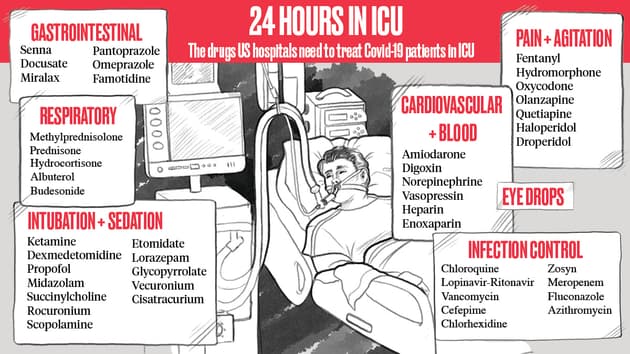

Ventilation requires the insertion of a tube into a patient’s airway – known as intubation. Once on the ventilator, the patient needs to be kept sedated. These processes require a range of drugs. According to one hospital, 24 hours on a ventilator for a patient with Covid-19 could require almost 50 different medicines, including those for intubation and sedation, as well as cardiac, respiratory and antimicrobial drugs.

Sedatives and painkillers are vital to keep the patient calm and comfortable. Without them, ventilated people can become agitated, especially in the unfamiliar setting of an intensive care ward, and try to pull out their breathing tube. The most critically ill patients can stay on a ventilator in intensive care for several weeks.

Pharmacists deal with drug shortages on a near-daily basis outside the coronavirus crisis, but the surge in demand for painkillers and sedatives due to coronavirus is exacerbating the problem. Amy’s hospital has more than trebled its use of some common sedatives and opioid painkillers. But, for now, despite a few close calls, her colleagues are still managing to find the drugs they need in their hospital. However, Amy is preparing for a scenario where they cannot order any more.

Louie Kenyon Crocket for TBIJ

Louie Kenyon Crocket for TBIJ

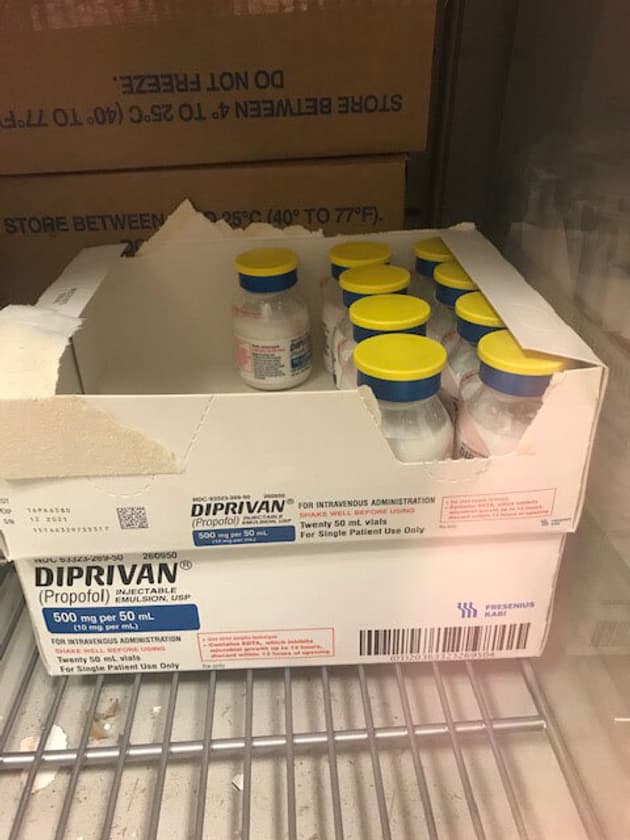

Propofol, a commonly used anaesthetic, is of particular concern. Supplies are running out in hospitals all over the world. Propofol is a fast-acting sedative that doesn’t stay in the body long. This means that, after being anaesthetised and intubated, patients can be kept lightly sedated for their stay in intensive care.

Patients take longer to be woken from drugs that give deeper sedation. As a result they may spend more time on a ventilator than necessary, preventing other patients from accessing the bed. Light sedation, on the other hand, means that patients tend to spend less time in intensive care overall, which lowers their risk of catching an infection or experiencing delirium, a severe state of confusion associated with a lack of oxygen to the brain and medications given in ICUs. ICU delirium can cause cognitive impairment, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and is a risk factor for early death.

“Propofol is the thing I’m most concerned about,” Amy said. “A lot of our patients are requiring really high doses to obtain sedation so we’re going through our supply really quickly and we’re having a hard time getting any, or being able to order more.”

Other hospitals have reported similar shortages. In an Instagram video, Mary Macdonald, a nurse in Oakland County, Michigan, describes how her hospital ran out of anaesthetic drugs.

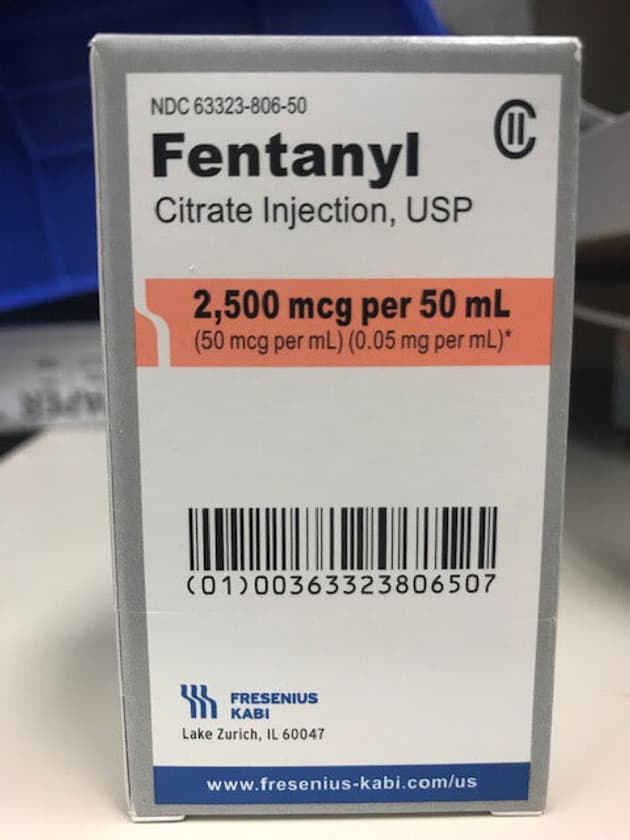

“Resources are very slim,” she said. “We have no medications to keep these patients even ventilated, let alone ventilators. Medications like fentanyl or propofol that would keep a patient sedated while they’re intubated we’re out of.”

Her hospital told local media it was sourcing from other facilities and directly from manufacturers, as well as assessing alternative products. A spokesperson said: “The safety of our patients, associates and providers is our utmost priority.”

The effects of the shortages are felt well beyond the US. Italy, Spain and France have all added propofol to their national drugs shortages list, which means that some drug manufacturers have flagged delays in supply.

Some producers of drugs commonly used in combination with propofol – including fentanyl, dexmedetomidine and midazolam – have reported shortages in the US, Italy, Spain and Germany. The UK has banned all four drugs from being exported in order to conserve supplies for its own hospitals.

Seeking alternatives

Drug shortages have an immediate impact on patient care. Amy, the clinical pharmacist in New York State, now has daily meetings with intensive care doctors at her hospital to tell them what she is able to order. Then they go through each patient’s drug regimen, substituting propofol with alternatives in order to conserve supplies.

The alternative drugs include benzodiazepines. Often, these are not the first choice for mechanically ventilated patients, as studies show that they can cause ICU delirium. This means that they are normally only used on patients who cannot tolerate the better options. Now, Amy is having to prescribe them more widely.

Dr Ali Haider – an interventional cardiologist who has been working at Baystate Medical Center, Massachusetts, during the Covid crisis – is also concerned.

Baystate Medical Center, Massachusetts

Baystate Medical Center, Massachusetts

“We’re seeing definite shortages of propofol, fentanyl and midazolam,” he said. Like others, Haider and his colleagues are using different medications than usual, including hydromorphone (sold under the name Dilaudid) for sedation.

“We’ve started using Dilaudid drips, which we normally do not use in the ICU setting,” he said. “Those are the powerful narcotics that we don’t often use but have resorted to due to the fentanyl shortage.”

Baystate Medical Center declined to comment.

Coronavirus cases are a double whammy for ICUs – not only are there more patients who need ventilation, but they need it for a week, or even two.

“The storm hasn’t hit here but we’re watching what’s going on in New York,” said Haider. “If I tried to guess, we’ve at least doubled or tripled our ICU capacity… the difference is here normally when someone is ventilated our goal is to get them extubated. They’re on the ventilator for a couple of days. In this situation you have a lot of people ventilated for a long period of time, so they burn through it [the medicine]. It’s the volume and the duration.”

Amy’s hospital is also using opioids more, despite the high risk of addiction. She hopes that patients will not be sent home and prescribed oral opioids because pharmacists and family doctors do not realise that the drugs were used as a stopgap in intensive care. The US is suffering an opioid crisis, with millions misusing prescription medications – about 128 Americans died from an opioid overdose every day in 2018.

For now, she has also started using ketamine as a sedative in order to conserve propofol. While ketamine is used regularly in other intensive care units, it has never been used before in hers. Normally the introduction of such a drug, which could cause significant harm to patients if used incorrectly, would be reviewed by a multidisciplinary group, approved by different committees and then rolled out with an education plan to teach nurses how to administer it.

In the middle of the crisis there is no time for that. “We rolled it out in 24 hours with me just doing as much on-the-fly education as I could,” said Amy. “That’s certainly less than ideal.”

Intensive care unit staff undergoing training in Moscow

Stanislav Krasilnikov\TASS via Getty Images

Intensive care unit staff undergoing training in Moscow

Stanislav Krasilnikov\TASS via Getty Images

She added that doctors at another hospital – NYU Langone Health – are performing a surgical procedure called a tracheostomy to get patients off ventilators after three days, therefore conserving medications.

During a tracheostomy, a hole is cut in a patient’s neck and a tube is inserted into the airway, usually temporarily. Patients don’t require such high doses of sedatives or pain relief with a tracheostomy than when on a ventilator.

Tracheostomies are typically carried out after at least a week on ventilation if attempts to have the patient breathe unaided have failed. Tracheostomies are considered high risk for the team carrying out the procedure, as it exposes people to droplets containing the virus from the patient’s throat.

Doctors at NYU Langone said that they had developed a new technique to help perform this procedure more safely, reducing the number of droplets sprayed from the throat. Carrying out the procedure on Covid-19 patients should “allow patients to be weaned from the ventilator sooner, thereby reducing the need for certain medications such as paralytic agents,” a spokesperson told the Bureau.

Pharmacists are concerned about shortages of propofol and fentanyl

TBIJ

Pharmacists are concerned about shortages of propofol and fentanyl

TBIJ

TBIJ

TBIJ

Looking ahead

Drug shortages are not a new problem. They can be caused by quality issues, which could mean that a batch has to be destroyed or recalled. There could also be a limited amount of profit to be made from a drug, which means that only a few manufacturers produce it. This leaves the supply chain vulnerable to disruptions if a manufacturer has issues.

In the US, for example, a surge in demand for certain drugs caused by coronavirus has compounded the problem. Manufacturers have not reported any issues with producing propofol, but there is a shortage because demand for the drug has skyrocketed.

With midazolam and ketamine, companies including the pharmaceutical giant Pfizer have reported shortages due to ongoing manufacturing delays and a surge in demand. Pfizer estimates that some ketamine and midazolam products on back order will not be available until 2021.

Got a Story?

We welcome tip-offs from the public and we always protect our sources

Find out how to work with usAmy’s hospital is drawing up a similar policy in light of the drug shortages. “We’ve never before done a tracheostomy just to reduce the analgesia medication,” she said. “That’s what we’re considering at our hospital now. They’re looking at starting a process for that in the next few weeks.”

If hospitals had the necessary drugs, Amy said, patients would not have to undergo these surgeries, which can leave visible scars.

The US Food and Drugs Administration said that it was working closely with manufacturers to ensure that they continue to notify the agency of any interruption in manufacturing that could lead to a shortage in supply. A spokesperson said that the agency was updating its shortage list regularly and communicating in real time so that hospitals have the most up-to-date information on drug shortages.

The pandemic has emphasised how opaque and fragile the global supply chain for medicines is. The raw ingredients for many American drugs are made in China, India and the EU. Manufacturing capacity in China fell as the coronavirus crisis worsened. As a result, India banned the export of 26 active ingredients for drugs to keep them for domestic production.

While European manufacturers have some supplies to continue making medicines, lockdowns are causing issues with distributing the drugs.

As the number of patients with Covid-19 grows daily at her hospital, Amy is hoping for a best-case scenario in which she can order “a ton” of propofol and fentanyl. In a worst-case scenario, she would have to use continuous anti-epileptic drugs to put patients who are on ventilators into a coma. She hopes things do not get to that point.

“At this point we’re all being creative and barely getting by,” she said, adding that what could happen in the coming weeks is never far from her mind.

Like many hospitals across the world, Amy’s is desperately increasing the number of intensive care beds with ventilators to treat the influx of coronavirus cases. But, she says, the machines will be “essentially useless” if the hospital cannot replenish the medicines needed to keep patients on them.

“Every time I see that they’re talking about getting more ventilators, I’m like, ‘What about the drugs?’” she said.

*Name has been changed to protect identity.

The Bureau is writing a series of stories on drug shortages related to the treatment of Covid-19. If you have a similar story please get in touch with Chrissie Giles, our global health editor, at [email protected].

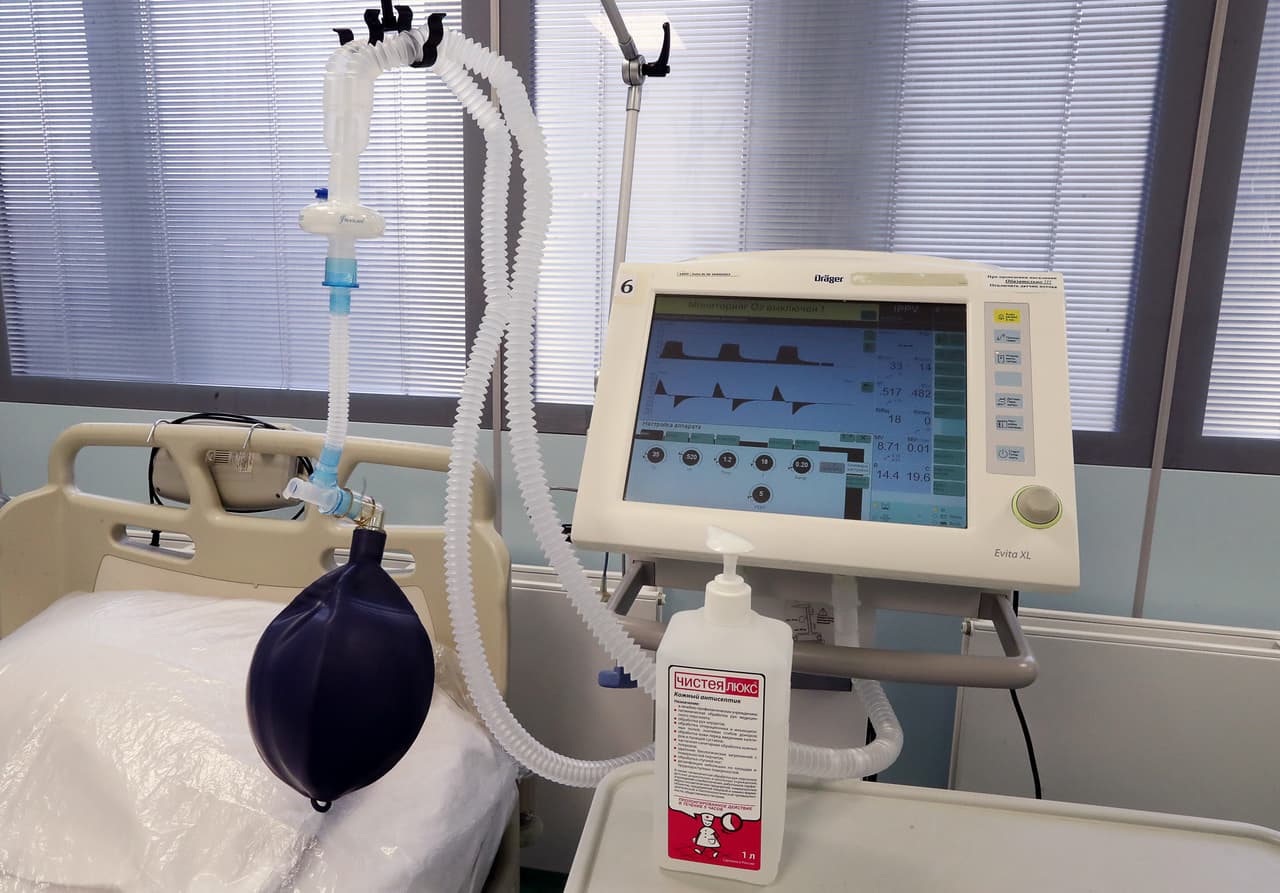

Main image: A ventilator at an intensive care unit in Moscow's Filatov City Clinical Hospital No 15. Photo by Stanislav Krasilnikov\TASS via Getty Images

Our reporting on coronavirus is part of our Global Health project, which has a number of funders including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.