PMI sidesteps global health treaty to lobby councils

One of the world’s biggest tobacco companies is using its pledge to “unsmoke” Britain as a cover to seek to regain influence in Westminster and with councils across the UK, experts have warned following an investigation by the Bureau.

A covert lobbying offensive by Philip Morris International to create a market for Iqos, a product which claims to “heat not burn” tobacco, has involved the company ignoring ministerial warnings and rules designed to limit tobacco industry influence.

Evidence obtained by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism has revealed that:

- Philip Morris wrote to government ministers and offered to work directly with local authorities and even schools, notwithstanding rules preventing tobacco companies influencing public health policy

- Despite this proposal being rejected on “ethical” grounds, the company then approached local councils directly with the same offer – even suggesting the use of Philip Morris-branded “quit” or “switch” vans

- Philip Morris has hired a former minister, No 10 advisers and lobbyists close to Boris Johnson to seek to gain access to officials, doctors and public health experts as part of its extensive lobbying efforts

- Participants invited to at least one of these events, including NHS workers, were left in the dark on Philip Morris’s sponsorship

The findings raise questions as to whether former officials may have broken bans on lobbying work, and whether Philip Morris tried to sidestep rules on tobacco companies’ dealings with governments.

Since Iqos’s UK launch in late 2016, Philip Morris has hired lobbyists with strong links to the Conservative party, sought to build a network of allies in cash-strapped local council and NHS services, and spent millions of pounds on public relations campaigns urging smokers to quit or switch to alternatives such as Iqos.

Philip Morris has positioned Iqos as a “reduced risk” alternative to cigarettes and an essential element of the government’s drive to make England “smoke free” by 2030.

However, there is no consensus on the evidence around heated tobacco products and their dangers, including the degree to which they are less harmful than cigarettes. There are also questions about how effective such products are in helping people to quit.

“Philip Morris is desperate to rehabilitate its image with decision-makers so it can influence public policy to the benefit of … Iqos,” Deborah Arnott, the chief executive of Action on Smoking and Health, said. “While it trumpets its commitment to a smoke-free future … in low- and middle-income countries it continues to aggressively promote smoked tobacco brands like Marlboro. Now is not the time to open the door to Philip Morris and allow it back into the fold.”

In late 2017 Philip Morris wrote to Theresa May with an offer to support local stop smoking services, a proposal it reiterated in adverts placed in British newspapers.

The offer was quickly rebuffed. Writing to Peter Nixon, the managing director of Philip Morris UK, the health minister Steve Brine reminded him of the UK’s commitments under an international treaty to protect public health policies from interference from the tobacco industry.

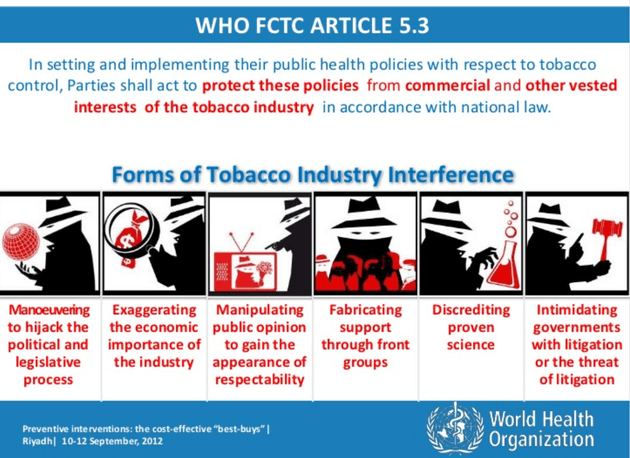

The World Health Organization treaty severely limits the tobacco industry’s interactions with officials. Its provisions are echoed in a voluntary public declaration, the Local Government Declaration on Tobacco Control, which applies the same rule to local councils.

The World Health Organization has strict rules to protect public health policies from the tobacco industry

The World Health Organization has strict rules to protect public health policies from the tobacco industry

“In working within the spirit of this commitment,” Brine wrote, “we do not believe it is ethical to accept funding to support local stop smoking services from a company that is still committed to producing tobacco products.”

Rather than heed the minister’s concerns, Philip Morris instead bypassed the government and directly approached officials in local authorities.

Just weeks after Brine’s letter, Philip Morris wrote to Burnley council with an offer to support stop smoking services in the area. “We are obviously interested,” the council chief replied, suggesting a meeting.

Burnley has some of the highest smoking rates in the country. Council spending on stop smoking services is under severe pressure and across the country funding has fallen by more than a third in the past four years.

In general, Iqos stores have opened in affluent metropolitan areas, such as Canary Wharf and Kensington in London, as well as central Bristol and Manchester, rather than places with higher levels of deprivation and smoking.

The Iqos shop in Kensington, west London

Iqos

The Iqos shop in Kensington, west London

Iqos

Iqos

Iqos

Philip Morris assured Burnley council officials that its offer would not involve the company advising smokers on quitting: “Philip Morris does not have the expertise to be giving cessation advice,” it said. Instead, it could potentially supply unsuccessful quitters with discounted or loan devices of smoke-free products through Philip Morris’s “switching programme”. It sent a mocked-up image of a Phillip Morris-branded quit/switch mobile cabin.

Burnley council said: “We were approached by Philip Morris, we listened to what they had to say, we rejected their offer.”

Philip Morris also approached Tory councillors it met at the Conservative party conference in 2017, where the company bought a “large and prominently positioned stand” to promote Iqos. The company also exhibited at the conference in 2018 and 2019, and has paid for a stand at the Local Government Association (LGA) conference in recent years, which it claimed led to dozens of approaches, some of which discussed potentially “partnering to end smoking locally”. The LGA told the Bureau it will no longer allow Philip Morris and other tobacco and vaping companies to exhibit at its conferences.

A councillor at the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead with responsibility for children’s services subsequently met with Philip Morris and the borough’s public health lead. Philip Morris floated the idea of sponsoring work around quitting smoking in schools. The proposal was not pursued by the borough.

As well as contacting councils directly, Philip Morris has also farmed the job out to the lobbying agency run by the Tory strategist Sir Lynton Crosby, CT Group. James Dee, one of its lobbyists who now works for a Conservative MP, approached officials in Leicester city council in April 2019 with Philip Morris’s offer of help. Northumberland, Lancashire and Norfolk county councils were also targeted. None responded to Philip Morris’s offer.

“Local authorities will not be fooled by Philip Morris’s attempts to paint itself as a public health partner,” says Nick Forbes, leader of Newcastle city council, who has led efforts to protect councils from tobacco influence. “The tobacco industry has constantly attempted to whitewash its role in spreading death and serious illness around the UK. This is just another example of Philip Morris trying to disguise its financially motivated strategies as a moral choice.”

This view is backed up by leaked internal emails that show Philip Morris attempted to use its offer of local funding as a way to leverage weaker rules on advertising heated tobacco products.

Concerns were raised over whether Kate Marley, a former adviser to David Cameron, may have breached a lobbying ban when she promoted Iqos at the Conservative party conference just over a year after leaving Downing Street. Philip Morris employed Mark MacGregor, a former chief executive of the Conservative party, as head of corporate affairs until last month.

Numerous parliamentary events have given the tobacco giant other inroads into politics. In 2018 Philip Morris was able to launch its “Hold My Light” stop smoking campaign in parliament, even branding the barriers at Westminster underground station. As recently as last month, Philip Morris invited MPs to “discover more about smoking in your area” at yet another event in parliament, this time hosted by Ben Bradley MP.

Philip Morris has also used the services of the former Conservative health minister Stephen Dorrell, an influential figure in UK health circles. In September 2019 Philip Morris paid for the drinks at an event organised by Public Policy Projects, an advisory firm chaired by Dorrell, aimed at healthcare and public health professionals and billed as an opportunity to discuss how to deliver the government’s plans to help people to quit smoking.

Local public health chiefs, stop smoking officials and NHS staff were told about a Philip Morris-commissioned survey that showed the need to educate frontline workers on the benefits of e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products to smokers who want to quit. Participants were unaware, however, about Philip Morris’s sponsorship of the wine and canapé reception that followed the debate.

Philip Morris told the Bureau: “We believe that open dialogue is the only way to solve a complex problem. Decisions on the future of public health are often made behind closed doors without any public accountability or scrutiny. Where we are excluded, we work hard to ensure that our views are heard.”

Forbes, of Newcastle city council, said that Philip Morris’s actions represented an attempt to paint itself as a public health partner for local authorities. “As long as the company remains in the tobacco business anywhere in the world, local authorities should have no dealings with them in any form that we can avoid.”

The Bureau newsletter

Subscribe to the Bureau newsletter, and hear when our next story breaks.

Header image: A mock-up of a Philip Morris branded Quit or Switch van in Blackpool

Our reporting on tobacco is part of our Global Health project, which has a number of funders. Smoke Screen is funded by Vital Strategies. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.

-

Subject:

-

Area: