How a doctor who has never seen you can say you're fit enough to sleep on the streets

Over 100 councils have paid a private company to assess vulnerable people applying for help with homelessness

Susan* could not face decorating for Christmas. She and her daughter Leah* are living in temporary accommodation, but their council, Bexley, had told them they needed to be out on 20 December, five days before Christmas. “It would break my heart to have to take them down again.”

Leah, 22, has autism, a learning disability and several mental health issues, including anxiety, ADHD, PTSD, severe obsessive compulsive disorder, agoraphobia and depression. “She’s on seven tablets a day,” Susan explained. A benefits assessment found she was not fit to work and had “severe functional disability relative to coping with changes”.

And yet the council had decided that she would have to cope, telling Susan and Leah they would be able to manage as well as “an ordinary person” even if “homelessness were to result in you having to sleep rough occasionally or in the longer term”. Despite Leah’s health problems, mother and daughter were found not to be in “priority need”, meaning the council had no obligation to house them.

It made that decision after commissioning reports from NowMedical, a private company that reviews medical cases to advise on whether someone is a priority case for homelessness support. The Bureau can reveal that at least 118 councils across England have used NowMedical, spending more than £2m of taxpayers’ money since the start of 2014.

Susan had already consulted Dr Mayur Bodani, a neuropsychiatrist, and later brought in Dr Rachel Daly, a forensic psychiatrist, who spoke with Leah and examined her. Dr Daly wrote that Leah was “extremely debilitated”, noting that her hands were raw from obsessively washing, that she thought about suicide and that she was unable to leave the house. “It would be a disaster for [Leah] to be homeless, given her current mental state,” she concluded.

Susan obtained copies of the NowMedical advice relating to her daughter, Leah

Maeve McClenaghan/TBIJ

Susan obtained copies of the NowMedical advice relating to her daughter, Leah

Maeve McClenaghan/TBIJ

Bexley council asked doctors at NowMedical to consult on her case four times, but at no point did anyone at the company talk to Leah, or to any of her regular doctors. Instead, in four reports, none longer than four paragraphs, NowMedical found she was no more vulnerable than “an ordinary person if homeless”.

After a legal battle, the council conceded Susan and Leah were in priority need but offered them a private sector flat that was unaffordable and unsuitable. Susan said she had no choice but to turn it down.

The council said it could not comment on specific cases, but said it “strictly adhered to the Homeless Code of Guidance” when assessing the vulnerability of clients.

“How have they come to this decision, when they have never met my daughter?” Susan asked. “There’s something very, very wrong with this system. It is unjust.”

People seen only on paper

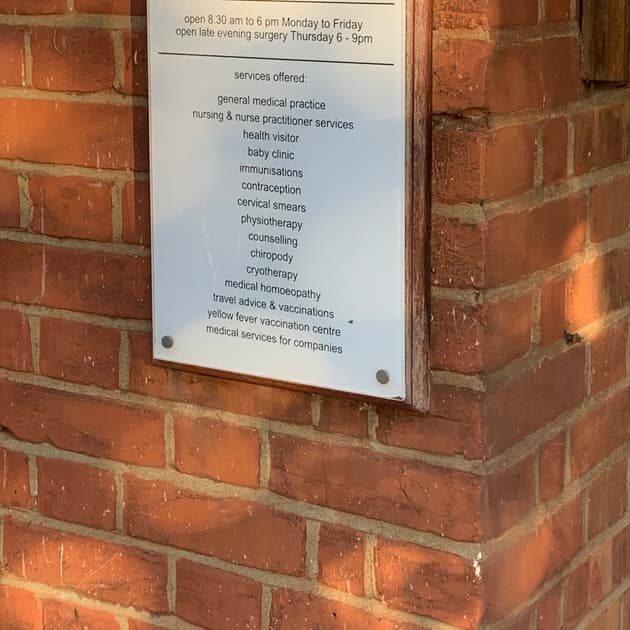

There are Christmas trees for sale on the common opposite the unremarkable GPs’ surgery in Chiswick that serves as the registered business address for NowMedical. On a bright December day dog-walkers in waxed jackets wander past the sign that lists the practice’s services: immunisations, physiotherapy, medical homeopathy, and then, at the bottom of the list, a clue. “Medical services for companies.”

Inside the warm waiting room, three well-dressed elderly women wait to be seen by the doctors as a receptionist cheerily greets return visitors.

From the same building, NowMedical assesses hundreds of people a week for councils and the Home Office purely on paper.

NowMedical charges £35 plus VAT for a basic report on whether someone is medically vulnerable enough to get long-term support to prevent or alleviate their homelessness. In most cases, this is produced solely on the basis of the council’s paperwork; the doctors working for NowMedical rarely meet the person involved, and do not regularly access their full medical records or talk to their GP. On its website, NowMedical says that it can turn reports around in a single day.

Lawyers familiar with the system told the Bureau that the company “churns out findings very quickly” and in some instances they believe NowMedical “diminish or downplay” the severity of applicants’ conditions or unsuitability of housing. The result, they warn, is that life-changing decisions are being made by councils without rigorous enquiry.

Through Freedom of Information requests the Bureau has learnt that the six-strong team, led by Dr John Keen, provides an estimated 14,000 assessments to councils per year, an average of 55 a day. In some cases the Bureau found them advising on applicants that live more than 250 miles away.

Decisions on homelessness support rest with councils. However, after years of cuts, many have no in-house medical experts to consult. Islington council spent £30,000 on NowMedical assessments last year and followed the company’s advice in every one of the last 10 decisions on which the company was consulted. One councillor said she was “a bit horrified” to hear the company rarely met those they were assessing. The council is actively looking for alternatives.

Leah is far from the only vulnerable person turned down for help by a council after a NowMedical assessment. Others included:

- A man with serious psychotic issues whose consultant psychiatrist had warned he was highly vulnerable;

- A 40-year-old man suffering PTSD;

- A suicidal refugee from Mauritania who had been subjected to slavery and human trafficking;

- Torture victims from Mexico and Iran, including a man who had been beaten so badly he still suffered pain in his feet;

- An alcoholic man with epilepsy, psychotic episodes and depression, who after being rejected for homelessness support ended up living in a shed.

In one case last year, Lambeth council was chastised by a judge for relying on NowMedical’s advice. An expert had examined Troy Guiste and found he had significant mental health issues, including hallucinations and suicidal thoughts, and that if he were to become homeless he “would be at risk for self-harm and suicide”. Lambeth took the advice of a doctor at NowMedical who was a psychiatric adviser but not a qualified psychologist and who reported Guiste was no more vulnerable than an ordinary person.

At a judicial review questioning the council’s decision, Lord Justice Henderson wanted to know why the council officer gave more weight to NowMedical’s recommendations. “They were less highly qualified than she is, and (more importantly) they had never met or interviewed Mr Guiste,” he said.

The GPs' practice that serves as the registered business address for NowMedical

Alex Sturrock/TBIJ

The GPs' practice that serves as the registered business address for NowMedical

Alex Sturrock/TBIJ

This is the sign outside the registered address

Maeve McClenaghan/TBIJ

This is the sign outside the registered address

Maeve McClenaghan/TBIJ

In another case, a judge questioned why Tower Hamlets council was favouring the opinion of a NowMedical psychiatric adviser who had not met the patient, over that of a practicing consultant who had examined him.

In a previous case a NowMedical adviser had told the court he did not meet applicants on whom he reports in about 80% of cases.

Heads I win, tails you lose

A document obtained by the Bureau that NowMedical used to train council officers on assessing medical vulnerability themselves provides startling insight into the company’s rubric.

The guidance offered to Bedford council’s housing team says that someone with HIV would not be considered “priority need” or vulnerable enough if they are “not on therapy”; and that a patient with cancer could get help if they are having “ongoing chemotherapy or radiotherapy” but not if the illness was “under investigation” or “in remission”.

“I fear it is a ‘heads I win, tails you lose’ situation,” Nicholas Nicol, a barrister who has successfully challenged such council decisions, told the Bureau. “They say if you’re not getting treatment your condition is not severe enough but, if you are, then you have the requisite support and, either way, you’re not vulnerable.”

Bedford council said it took NowMedical advice into account alongside other factors, including government guidance and regulations.

While some councils rely on applicants’ GPs or other medical records, scores across the country opt to use NowMedical’s service. Tower Hamlets council used to spend £110,000 a year for in-house medical expertise, but paid half that, £42,000, to NowMedical in the past year; Southwark paid £51,000. The company has been paid more than £2.2m by 118 councils in England since 2014.

Many lawyers told the Bureau they feared councils were using the advice of the company as a way of out-sourcing tough decisions on homelessness and housing applications. Cash-strapped councils across the country struggle with paltry levels of council housing stock and instead must house homeless people in costly temporary accommodation.

“It is a terribly flawed system, it is obviously a kind of gatekeeping exercise for councils,” said Simon Mullings, a housing law case worker. “And it is a very useful, arms-length, quick and cheap way to protect your case workers from the trauma of having to make these decisions on people’s lives.”

Nicol added: “I am not saying there is any conscious bias, but if they continually said this person is vulnerable, well, they just would not be used. They are delivering, in the broadest terms, the advice that their customers want to hear.”

In all instances, the decisions to deny housing to applicants are made by the council. At no point is NowMedical making these decisions; they are paid to provide medical assessments.

Councils have also paid the company to advise on whether housing is suitable. In one case, NowMedical said that a ground floor flat would be optimal but that a first floor flat with a balcony was was an “acceptable alternative” for the family of a six-year-old girl with severe autism, despite the fact that she had no concept of danger and had climbed up onto the balcony and put herself at immediate risk. The flat was still suitable, the company said, because a fall from that height was “unlikely to be fatal”.

Nor are councils the only branch of government seeking NowMedical’s advice. Last month OpenDemocracy revealed that the Home Office asked the company to determine if a 55-year-old woman who was awaiting spinal surgery was fit for the 10-15 hour deportation flight to Sudan. A NowMedical doctor determined she was, recommending that she did “frequent exercise whilst on board”.

After being contacted by the Bureau and Susan’s lawyers, Bexley council is letting the family stay in their flat over Christmas. The council is reviewing whether it was right to offer Susan only a private rental flat, but in the meantime it has told her to prove that she is searching for a place of her own every week.

She said: “I’m glad we’re here for Christmas, at least there’s that, but after … we’ll see. They clearly have no plan to help us long term. I have to keep fighting.”

A spokesperson for NowMedical said: “Local authorities have the legal responsibility to make, and must make, decisions on a priority need. NowMedical does not and cannot make any decision on behalf of a local authority. We simply provide medical opinions to assist the local authority to understand the medical records and make its decisions, ensuring that those who are most vulnerable receive the accommodation and fair treatment to which they are entitled. Our opinions are only a part of the information that councils consider. The law uses the comparators of “vulnerable person” and “ordinary person”. Our reports use this language.

“Opinions we give to the UK Border Agency consider the statutory test of whether an individual is “unable to leave the UK”. This is not an opinion on whether an individual is “fit to fly” on a specific day. No such language is used in NowMedical reports.

“NowMedical’s registered doctors and psychiatrists are not required to physically examine patients in order to provide the opinion that the local authority/UKBA has asked for. This approach is one which the Courts and General Medical Council have readily accepted to be entirely correct.

“There are may Court judgments which are positive, commending our medical expertise, and where our assessments – based on having applied the correct test to the evidence – have been preferred to the treating GP.”

Homeless or not?

In England, those threatened with or experiencing homelessness can approach their local council for help, assuming their immigration status means they are eligible for public funds. After an initial period of support where the council will try to end or prevent their homelessness, they will be assessed to see if they are eligible for long-term help.

The council will consider whether the person is intentionally homeless, how long-standing and strong their links to the local area are and, crucially, if they are so vulnerable that they warrant help.

People may be considered vulnerable if they have a physical disability, mental health issues, or if they are elderly, fleeing domestic abuse or have been in care or the military. But being considered vulnerable is not enough. The council housing officers will then decide if the person is significantly more vulnerable than an ordinary person would be if they became homeless. It is here many cases fall down.

If they decide the person does not meet that bar, then they are assessed as “non-priority need”. They can appeal the decision internally and even take the case to judicial review, if they can find the funds. However, without the decision being overturned, the council is under no obligation to find them housing, leaving them with few options to keep them off the streets.

This article was updated on March 6 2020 to include a statement from NowMedical.

Header image: A rough sleeper outside a shop in Brighton. Credit: Alamy

Our reporting on the housing crisis is part of our Bureau Local project, which has many funders. Our work on the housing crisis was supported by the Bertha Foundation. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.