Record number of fires rage around Amazon farms that supply the world's biggest butchers

The summer’s Amazon fires were three times more common in the areas supplying cattle to abattoirs than elsewhere in the rainforest.

The findings raise yet more questions about the role of cattle ranching in the world’s biggest single environmental crisis. Experts widely agree the fire emergency this year was a direct result of increased deforestation, as felled vegetation was burnt off.

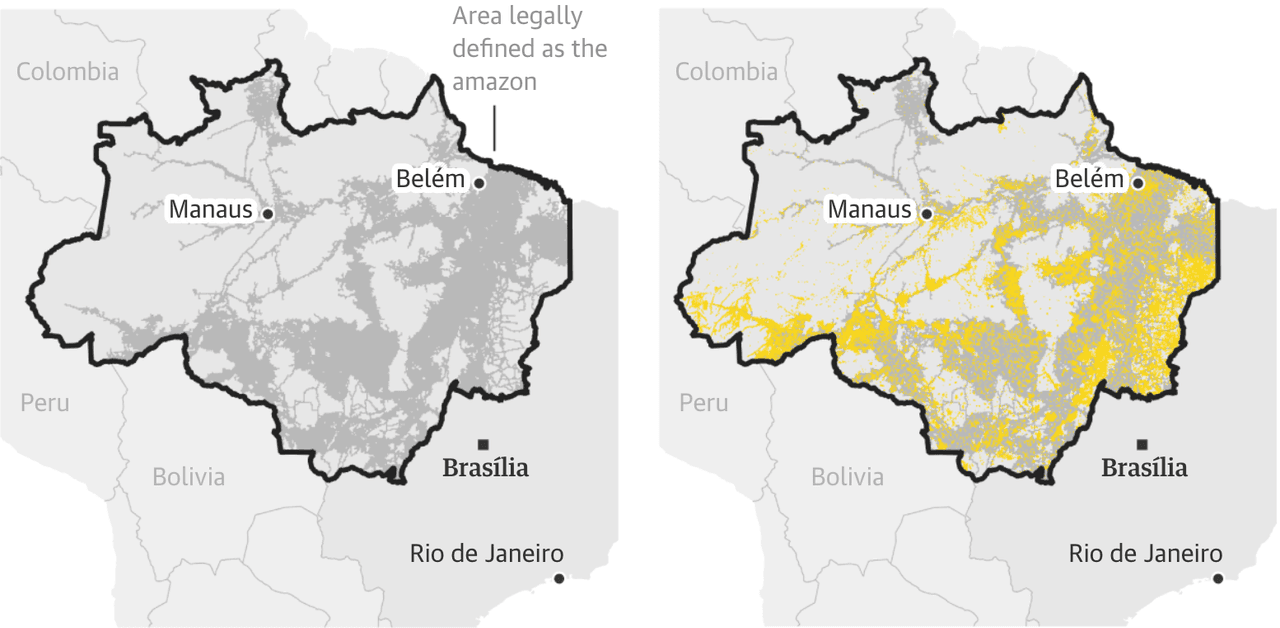

A joint investigation by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and the Guardian has found that in Brazil nearly 70% of the fires occurred in the estimated “buying zones” of cattle slaughterhouses – despite these zones accounting for only 40% of the Brazilian Amazon.

Using research by the Brazilian NGO Imazon, our investigation has shown that from July to September there were more than 554,000 satellite fire alerts in the Brazilian Amazon. Of these alerts, issued by Nasa’s VIIRS sensor, nearly 376,000 occurred in the probable operating area of the beef industry.

Some of Brazil’s – and the world’s – biggest meat companies buy cattle from the region. More than a quarter of a million fire alerts were issued in the estimated buying zones of JBS, the largest supplier of meat globally. Its factories are known to export to Europe, including to the UK.

There were more than 66,000 fire alerts in the probable buying areas of Minerva, the second largest Brazilian beef exporter, and almost 80,000 around abattoirs owned by Marfrig.

Multiple other companies could have been buying from the same areas because the estimated buying zones often overlapped, but these three meatpackers dominate in Brazil’s Amazon. They account for nearly half of the cattle slaughtered in the region, according to Imazon.

JBS, Marfrig and Minerva told the Bureau they were committed to “zero-deforestation” supply chains, and that they all monitor their suppliers to this end. However, Marfrig admitted that huge gaps in its audit trail mean more than half of the cattle it buys could have been bred or raised elsewhere. That could include illegally deforested Amazon land.

“Theoretical correlation based on estimates is not causation and is misleading,” a JBS spokesperson said. “JBS is actively working to bring together other important stakeholders and companies to join forces to preserve the Amazon.”

The company added: “If farms are deemed non-compliant with our sustainable sourcing policies for any reason, including deforestation, they are blocked from our supply chain ... We are not involved in, nor do we condone, the destruction of the Amazon.”

Marfrig also said it blocked any farms found to be involved in deforestation, and that it began monitoring fire outbreaks in August this year. “Whenever any overlapping of areas between the properties and the fire outbreaks is identified, there is an alert for the purchase to be reevaluated,” it said.

Minerva said there was no evidence it had bought animals from ranches where fires had occurred, and blamed this year’s crisis on the weather. It said “there is no proven connection with agribusiness activities”.

While JBS, Marfrig and Minerva say they are confident that the cattle they buy do not come from illegally deforested areas, they also accept that they cannot know the origin of many because livestock are often moved between breeding, raising and fattening ranches. There are thousands of cattle ranches in Brazil, many of which specialise in a different stage of the rearing process.

The beef industry is seen as one of the major causes of deforestation in the wider Amazon region. Cattle ranchers are responsible for 80% of land clearing in every country with Amazon forest cover, according to the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies.

JBS, Minerva and Marfrig all admit they cannot monitor the earlier ranches in their supply chains. “As of today, none of the players in the industry are able to trace indirect suppliers,” said Minerva.

Marfrig told the Bureau that 53% of the cattle it slaughters originate from these indirect suppliers. Research from the University of Wisconsin suggest that is true across the beef industry in the Brazilian Amazon.

All three companies said they were working with the government or NGOs to address this blindspot in monitoring.

JBS said: “We have been working with local authorities, government and wider industry to gain access to the data and tools required to address this issue.” Marfrig said it requests cattle purchase information from its direct suppliers, while Minerva said that more law enforcement was needed at all stages in the chain.

Responding to the investigation, MEPs called on the EU to block beef which may be linked to deforestation. “It is absolutely urgent that the EU puts in place a legal duty on European companies to ensure that their supply chains are free of deforestation,” said Heidi Hautala, a Finnish MEP.

“It cannot be the responsibility of a consumer to ensure that the products on European markets' shelves are sustainably produced. The consumer has to be able to trust that only responsibly produced items are sold in Europe.”

The French MEP Manon Aubry said the findings showed a need to rethink the EU-Mercosur trade deal, which, if ratified, would open the gates to reduced-tariff beef imports from Brazil and other South American countries.

“We need to change the rules with an international binding treaty forcing transnational companies to pay the price if they destroy the environment,” she said. “The EU also has to question the impact of free trade agreements that are detrimental to both the planet and the people. A deal with the Mercosur would worsen the situation and accelerate deforestation in Amazonia.”

Smoke rises from fires burning near Itaituba in Pará state, Brazil

Reuters

Smoke rises from fires burning near Itaituba in Pará state, Brazil

Reuters

There were 128 active slaughterhouses in the Brazilian Amazon in 2016, when Imazon collected data to estimate the beef buying zones. The research team gathered information on the maximum distances from which each slaughterhouse could feasibly source cattle through phone interviews with staff or taking averages based on meat plants nearby or similar factories in the same state.

They then modelled this data against local factors, such as roads, navigable rivers and seasonal weather patterns, to estimate the maximum potential buying zone for each slaughterhouse.

Using methods designed by the non-profit sustainability project Chain Reaction Research, the Bureau mapped Nasa fire alerts archive data onto Imazon’s buying zones.

Fires were also found on at least three farms known to sell cattle directly to JBS slaughterhouses. Working with Repórter Brasil, the Bureau found at least one of these slaughterhouses exports beef and leather globally.

“Our findings illustrate that fires and deforestation continue to take place in JBS’s supply chain, despite the company’s policies and commitments,” said Marco Tulio Garcia, who led the research at Chain Reaction. “It is of the highest urgency that JBS addresses these issues.”

There is no evidence that these fires were started on or by farms supplying JBS, but the very existence of a patchwork of ranches in the rainforest could be helping to exacerbate the overall effect of fires started elsewhere. “The whole local climate is drier because you’re getting less evaporation from the trees,” said Yavinder Malhi, professor of ecosystem science at Oxford University.

Over the summer, global attention was focused on the fires in the world’s largest and most biodiverse rainforest. Data released in August by both Nasa and the Brazilian satellite agency INPE showed 2019 had been the most active fire year for the Brazilian Amazon in nearly a decade. There were three times as many fires that month compared with the same month last year, according to INPE.

Experts say the increase in fires was directly caused by an increase in deforestation: the intentional burning of trees that had been felled months before, rather than random wildfires. “Once you clear forest to make a ranch, you have lots of dead materials lying around and then the farmers wait until the dry season to burn off that material,” said Professor Malhi.

Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon dropped drastically in the mid-2000s, but data released in November showed it increased by 30% in the year to July 2019. The country’s pro-agribusiness, climate-sceptic president, Jair Bolsonaro, took office in January 2019.

In July the European Commission published a communication on deforestation to address “the fact that the EU consumption of food and feed products is among the main drivers of environmental impacts, creating high pressure on forests in non-EU countries and accelerating deforestation”.

The commission pledged, among other things, to assess the need for regulation to “increase supply chain transparency and minimise the risk of deforestation and forest degradation associated with commodity imports in the EU”.

The Austrian government recently blocked the Mercosur deal over concerns about the Amazon fires crisis – as well as the potential damage to Austria’s farming sector – and the French and Irish governments have also threatened to do the same.

The Irish government told the Bureau it was commissioning an external assessment of the deal’s possible impacts on the environment and Ireland’s economy, which will inform whether it votes to ratify the agreement next year.

In the UK, the Liberal Democrats recently announced plans for a legal “duty of care” on British businesses, stopping them from buying from overseas companies causing environmental harm, including forest destruction. “If British companies buy their beef and continue to support this industry, they are not meeting their duty of care and the government must take action,” said Wera Hobhouse, the party spokesperson on climate change and the environment.

Header image: Getty Images

Our Food and Farming project is partly funded out of Bureau core funds and partly by the Hollick Family Foundation (for 2020) and The Guardian. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.