Juul spreads over the world as home market collapses in scandal

The embattled American vape company Juul is pushing foreign governments to ditch strict e-cigarette regulations as it aggressively expands across the globe in an attempt to offset lost profits in the US.

Juul, which sells sleek e-cigarettes and flavoured nicotine “pods” that have become a craze among American teenagers, is planning to enter new markets in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, South America and Asia. As it expands, the company has spent millions of dollars lobbying politicians in an attempt to pre-empt or roll back relevant regulations on products in several different countries.

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism can reveal Juul has met politicians, regulators and officials to lobby on vaping rules, putting forward health claims it cannot legally make in the US. It has also launched glossy marketing campaigns that attempt to portray the company as a responsible alternative to smoking – a far cry from the adverts that first landed the brand in hot water in the US.

The company has come under intense pressure in its home market and is facing hundreds of lawsuits as well as state and federal investigations into claims its early advertising hooked a generation of teenagers on nicotine.

What is Juul?

Juul’s founders Adam Bowen and James Monsees met over smoking breaks at Stanford University, where they studied product design. Intrigued by the idea of making smoking less harmful and more socially acceptable, they turned their final thesis into an e-cigarette company, Ploom, in 2007, which became Pax Labs in 2015, and Juul Labs in 2017.

The Juul device has gone through many iterations since the prototype. It now looks like a high-end USB stick, its sleek design a far cry from some clunkier competitors, earning it the title of “the iPhone of e-cigarettes”. A puff delivers a vaporised dose of nicotine, the addictive substance in tobacco.

The company also sells pre-filled nicotine pods that click into the device and act as a mouthpiece, which come in flavours like “apple orchard”, “mango nectar” and “alpine berry”.

Juul borrowed a process developed by the tobacco company RJ Reynolds to make its cigarettes more palatable when developing its nicotine formula; the company uses benzoic acid, a common food preservative, to produce “nicotine salts”. This prevents the throat irritation that normally occurs when smoking.

It also means a higher dose of nicotine can be inhaled directly into the lungs, entering the bloodstream more quickly. Researchers say this combination allows users to get a puff that matches the addictiveness of a Pall Mall cigarette.

Juul’s stronger pods contain 59mg/ml of nicotine, meaning one pod is the equivalent to a pack of 20 cigarettes. The stronger pods are banned in the UK and Europe under EU regulations, where nicotine strength is capped at 20mg/ml.

In the UK, at £10.99 for a set of four pods, Juul costs roughly the same price as the average pack of cigarettes while delivering more nicotine. And unlike cigarettes, which burn out, users can keep vaping on until the device runs out of battery, which takes about a day of use.

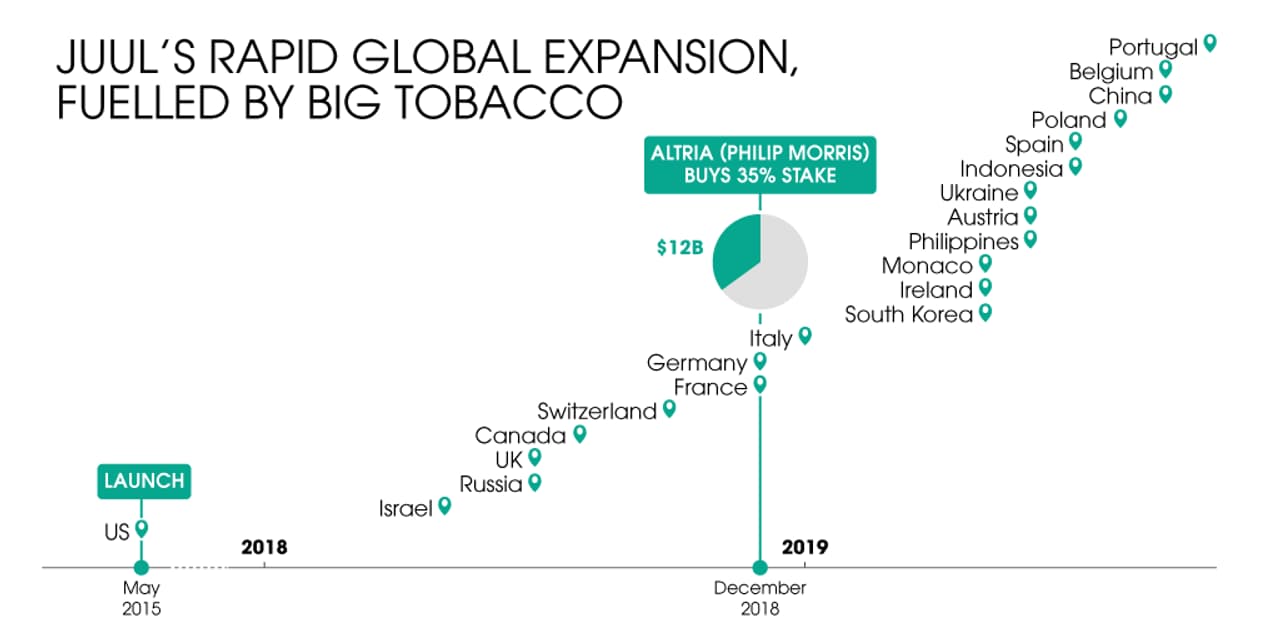

Although Juul’s influencer-led early marketing would later prove a problem, it created a trend that propelled the company from a small start-up to a market leader in the US. In late 2017 it held 32% of the market; by November 2018, it had 76%. As it grew, Altria, one of the “big six” tobacco businesses, invested $12.8 billion for a 35% stake. Juul forecast revenues of $3.4 billion for 2019, triple what it generated in 2018, according to Bloomberg.

Juul’s meteoric rise ended when concerns over the teen vaping “epidemic” in the US led to congressional hearings and multiple investigations into its early marketing practices. While e-cigarettes expose users to fewer carcinogens than traditional ones, scientists are still learning about the health effects of vaping, especially on young people. The damaging effect of nicotine on teenagers – harming the part of the brain responsible for memory, attention and learning – is well known, but the long-term effects of inhaling the vapour are unknown.

In October 2019, as the outcry raged in the US, Altria wrote down $4.5 billion of its investment in Juul, and adjusted its predictions about the company’s international sales.

Despite the mounting criticism in the US – including a raid by the Food and Drugs Administration on Juul’s offices – investor presentations show that Altria is confident international revenues can offset the predicted slump in US growth. It hopes Juul’s global sales will match domestic ones within four years.

Juul is requesting private meetings with ministers and ambassadors across the world to promote its e-cigarettes, influence countries’ vaping laws and stop taxes being slapped on its products. Lobbyists have suggested Juul devices can help people quit nicotine altogether, a claim the company would be banned from making in the US, according to transcripts of meetings seen by the Bureau.

Its lobbying offensive even includes offering to help governments write e-cigarette rules, despite the fact that tobacco companies are banned from interfering with public health policy under an international treaty.

Juul said it wants to work with regulators and policymakers to provide “an industry point of view on regulations”.

Experts are worried other countries could face their own teen vaping “epidemics” if Juul is not adequately regulated as it expands.

“Cigarettes are not cool in most communities. But Juul is cool with youth in a number of communities,” said Dr Vinayak Prasad, head of tobacco control for the World Health Organisation (WHO). “That’s a hugely powerful strategy for the tobacco and related industries, to let these products get in and capture significant market share, getting 6-8% of the young people addicted to nicotine. That’s a huge market for the future.

“Apart from the known harmful effects of nicotine on the developing brain, nicotine is addictive and could lead people, particularly young people, to take up more harmful forms of nicotine or tobacco consumption.”

Juul's early advertising has been criticised for appealing to a young audience

Juul's early advertising has been criticised for appealing to a young audience

A recent wave of mysterious lung illnesses, causing dozens of deaths and thousands of hospitalisations in the US, has compounded Juul’s troubles, although most of the cases were linked to black market products and not Juul devices.

However, the cases have re-ignited fears over the safety of e-cigarettes and a public health debate in which the benefits of switching smokers to a less harmful product are pitted against the risk that non-smoking teens take up vaping.

“The iPhone of e-cigarettes”

Juul was launched by Pax Labs in 2015, and within three years was America’s most popular vape. Dubbed “the iPhone of e-cigarettes”, it combined slick design with enticing flavours like “cool cucumber” and “creme brulée”.

Its first advertising campaign, Vaporized, featured young models posing and dancing against brightly coloured backgrounds. Its ads appeared on huge screens in New York’s Times Square and page spreads in Vice. It threw yacht parties, hosted rooftop cinema clubs and held concerts. The brand even funded summer camps for children as young as eight and went into schools, advertising e-cigarettes as “totally safe”.

The devices, which could be used discreetly and without releasing much vapour, surged in popularity. High school students bragged of taking puffs during lessons without anyone noticing. A language evolved among teenagers: “ghost ripping” meant taking a discreet drag; “Juuling” became a verb. On YouTube and TikTok, teens shared tips on blowing rings and shapes with vapour and decorating their Juuls with stickers.

One of Juul's events in LA

Standford Media Library

One of Juul's events in LA

Standford Media Library

Smoking rates in America fell sharply from 2013, with e-cigarettes like Juul contributing to the decline. Yet vaping has been accused of creating a new public health problem: addictions among non-smoking teenagers. In 2011, 16% of high school students regularly smoked and just over 1% vaped; the number of smokers fell to 8% in 2018, but the number vaping soared to almost 21% – more than had smoked before e-cigarettes took off. The FDA declared it an “epidemic” and said Juul was responsible.

Juul said: “We have never marketed to youth and do not want any non-nicotine users to try our products.”

Juul has been hit with hundreds of lawsuits in which Americans claim they were not warned about the potential dangers of vaping, or that the products contained nicotine. Juul disputes this. Some allege they have suffered respiratory issues, seizures, strokes, mental health and behavioural problems as a result of their addiction to Juuling. Lisa Vail, from Florida, told the Bureau she believes her 18-year-old son Daniel died from respiratory problems due to a heavy Juul addiction.

The company has until May next year to submit an application to the FDA to continue selling its products. It will need to prove they are “appropriate for the protection of public health”.

A host of cities and states have already tried to ban vapes like Juul or flavoured nicotine, including a blanket ban in its home city, San Francisco. As it fought these measures, Juul’s bill for lobbying in Washington soared from $120,000 in 2017 to more than $3m in the year so far.

Elsewhere, it gave nearly $19m to support PropC, a ballot measure to overturn San Francisco’s vape ban, which was unsuccessful. It set up The Switch Network, recruiting members of the public to contact state and local politicians to promote vaping. Critics accused it of “astroturfing”, dressing up a well-funded lobbying campaign as a grassroots movement.

Stefanie Miller, an investment adviser who specialises in regulatory risks, said the backlash against Juul in the US will severely constrict its American market. “I would be very concerned if they weren't simultaneously trying to grow in other markets,” she said.

Altria told investors it expects hardly any earnings from Juul this year as it expands abroad. Juul has launched in 21 countries outside the US, including Canada, Russia and much of Europe, but has plans to open in more markets across Europe, the Middle East and Asia-Pacific, and has advertised for jobs and lobbied governments in South America.

Amid the backlash at home, the company made extensive efforts to show it has changed and suspended all “active” lobbying in the US – but the Bureau uncovered a very different picture across the world.

Rewriting the rules

For decades tobacco companies lied about the lethal effects of their products and tried to subvert government policies that would harm their profits. In 2003 a landmark international treaty from the World Health Organisation was ratified by more than 180 countries. One key clause asks governments to protect public health policies from the vested interests of tobacco and e-cigarette companies, limiting interactions and avoiding partnerships.

Yet the Bureau has found concerns that Juul is seeking to shape how countries write the rules that will govern its products, in violation of the treaty.

In a private meeting with a government minister in Vietnam in August this year, lobbyists said Juul was working with a “number of ministries” formulating the country’s new decree on vaping. They offered to consult with the Ministry of Health on the new law, according to a transcript of the meeting seen by the Bureau. Vietnam is a signatory of the WHO treaty. Juul told the Bureau the interaction did not violate the treaty.

“Juul clearly has a systematic global strategy to meet with government officials in private behind closed doors,” said Matt Myers, president of the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. He added that in his opinion the strategy violated the WHO treaty and repeated methods the tobacco industry has used to undermine reasonable regulation. “[It] is exactly what the tobacco industry did: replace good science and good evidence with well-paid lobbying and PR firms which operate in secrecy.”

Juul lobbyists have also been telling officials the company’s products can help people quit smoking, a claim the company cannot make in America because the FDA has not approved e-cigarettes for smoking cessation. To do so, the FDA would have to review the evidence, only some of which backs the claim; other studies have shown people continue to smoke and vape.

“When Juul tells government officials outside the United States that its products have been shown to help people quit using nicotine altogether it is inconsistent with the evidence, it is inconsistent with their internal documents, and it reflects a willingness to say things that they know aren’t true,” Myers said.

In the meeting in Vietnam a Juul lobbyist claimed its products could help wean people off nicotine entirely. He said: “What you can do, is when someone transits from a cigarette to Juul you can eliminate the combustion and you can offer them lower strength pods over time [...] Over time with our technology we can then address the second phase and migrate people down nicotine to zero consumption.”

The lobbyist added that the company is looking to explore whether vitamins could be vaped as a more effective way to get them into the bloodstream, which concerns experts who say there have been no long-term studies on the safety of absorbing nutrients through the lungs.

An ambassador from a southern African country, who wanted to remain anonymous, told the Bureau that Juul lobbyists gave him the same pitch. He said: “They said they had success stories of people heavily addicted to smoking who switched to Juul and then quit nicotine altogether.”

The lobbying is as persistent as it is pervasive. Juul approached the Mexican government repeatedly, but its representatives were told they would get no further meetings, as there are strict controls on ministers’ contact with tobacco companies.

In Indonesia, campaigners are concerned about Juul’s rise. At Cilandak Town Square, a shopping centre in Jakarta, the Juul shop – its largest in Asia – sits near a Baskin Robbins and a Starbucks. Experts fear the brand is targeting young people.

Dr Rafendi Djamin, of the Indonesian National Civil Society Coalition on Tobacco Control said that the company was aggressively expanding, while e-cigarette regulations had been in limbo for two years. He said: “It has set up kiosks in places that teenagers hang out.” He fears a rise in teen vaping on top of the country’s soaring teen smoking rate. “Vaping in public has become stylish for young people. They idolise vaping.”

Move fast and break things

Juul has been fighting restrictions on its products since its global expansion began. Its first international market was in Israel, where it launched in May 2018. Within three months, it had been banned by the government because officials believed Juul's stronger nicotine pods were “a grave risk to public health”. Juul launched legal action, with the case to be heard this month, and began a pro-vaping PR campaign.

In India, Juul was said to have captured a third of the booming e-cigarette market before it had formally launched. In preparation, the company hired PR companies and thinktanks to seed the media with messages about the benefits of e-cigarettes. However, just as Juul was set to start selling there officially, the central Indian government banned vapes, fearing e-cigarettes were a growing health risk to young people.

Soon Plume Vapours and another local e-cigarette importing company, filed petitions against the ban. When the case was opened at a Calcutta court in October, two Juul officials were said to be sat beside Plume’s founder. Defending the ban, the Indian solicitor general Aman Lekhi told the court this was a “proxy case for Juul”. Juul told the Bureau it has “supported Plume Vapours in the past” but is not part of the legal case.

After launching in the Philippines in June this year, Juul is now fighting the government’s proposal to raise taxes on e-cigarettes. Juul’s stronger 5% nicotine pods, which are banned in the EU, would be badly hit.

During hearings in the Philippine senate in September, Kenneth Bishop, President of Juul Labs Asia-Pacific, claimed that Juul’s products should be taxed less because they were less harmful. He also told legislators that the company was now acting responsibly. He said: “We have done some things that we are not proud of in the past but we have taken aggressive and industry leading actions to mitigate any risks of exposing our products to youth or appealing to youth.”

Yet, fearing a surge of vaping-related illnesses as the US has seen, the Philippines’ Department of Health has now asked all hospitals to formally report any cases.

Shane MacGuill, an analyst at Euromonitor, told the Bureau Juul’s rapid expansion and “move fast and break things” mentality could harm its perception among regulators and the public.

“I think people in general don't really feel comfortable with where [Juul] think nicotine should be used and shouldn't,” he said, “They sort of drove a cart and horses through all of that. And I think it's really a time for reflection for them.”

"He was like a drug addict" — 13-year-old hooked on Juul

In March Jennifer* picked up her 13-year-old son Joshua* from a counselling session. Over the past six months he had changed from a happy, outgoing child to one riddled with anxiety. His Tourette’s syndrome meant he had always suffered from involuntary movements, called tics, but he never appeared to have mental health problems before.

That night, he started begging for a mango-flavoured Juul. When Jennifer refused to buy him one he became distressed. “He had a meltdown,” she said, “that’s when we realised how bad it was.”

Joshua had been caught with a Juul before but his parents had no idea he was addicted. They believed it explained the profound personality changes they had witnessed in their son: Joshua had become constantly anxious, regularly calling his mother and asking her to take him home from school and retreating from his friends. They had thought it was because he was being bullied, and had taken him out of public school and enrolled him in a private school.

After the meltdown, Jennifer and her partner asked Joshua why he was using e-cigarettes, He said he loved Juul’s mango flavour and it helped with his Tourette’s, making him feel more relaxed and in control of his tics. “He loved the buzz, he loved the way it tasted,” Jennifer said.

They realised the extent of his addiction at Easter, when they travelled to stay with family. Joshua spent the holiday crying and begging for nicotine, saying it was the only thing that made him feel better. “He was like a drug addict,” Jennifer said.

A day later, he sent his mother a text message saying he was going to kill himself; that without nicotine he felt out of control. His parents immediately took him to an outpatient behaviour centre and he began counselling with a specialist in nicotine addiction.

But his parents couldn’t stop him Juuling. He paid people on social media to bring a device to his house. He would ask total strangers for a hit. His mother banned him from the school locker room because children were using e-cigarettes there, despite the school searching bags.

Things came to a head in May when his mother found him raging and crying after school. He had taken a hit of Juul before baseball practice and hit another pupil over the leg with a bat. “That was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” Jennifer said.

Jennifer started testing Joshua using nicotine strip kits she bought online. Despite her best efforts to keep him away from e-cigarettes, he would often test positive. “In his mind, it helped him if he was having issues with kids. If anyone bothered him, it relaxed him… But he didn’t bother to think about how it can affect you mentally.”

Finally, in September, the family heard some news that made Joshua take stock of his addiction. A family friend’s 27-year-old daughter was rushed to hospital with pneumonia and died; her family blamed her death on her vaping habit. “It became real,” Jennifer said. “The consequences became real to him.”

Joshua continued with counselling, and his mother has kept randomly testing him for nicotine. As a result, he has not used a Juul in two months. His parents are suing the company, claiming he will deal with the effects of a nicotine addiction for the rest of his life.

Jennifer believes Juul’s marketing and flavours was attractive to children like Joshua. She wants to see more severe consequences for shops that sell e-cigarettes to minors. She understands the devices can help people switch from cigarettes, but believes the controls to stop teenagers becoming addicted to vaping aren’t adequate. She said: “If it’s helped you that’s great. But there are so many things that need to be done and put in place prior to putting it on the market to protect those it wasn’t intended for.”

Juul said it was focusing on underage use and developing technology to curb underage access. A spokesperson added: "With that in mind, we disagree with the allegations made in these claims and look forward to presenting the facts.”

*names changed to protect identities

Additional reporting by Rahul Meessraganda, Sharon Kelly and Ben Stockton

Illustration by Rebecca Hendin

Our reporting on tobacco is part of our Global Health project which has a number of funders. Smoke Screen is funded by Vital Strategies. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.