‘Invisible’ pharmacists selling knock-off drugs: the rise of antibiotic resistance in Cambodia

Quack pharmacists in Cambodia are fuelling the rise of drug resistant bacteria by incorrectly peddling antibiotics, a study has found.

For the first time researchers have interviewed Cambodia’s “invisible” drug sellers – those who sell from their own homes, visit customers’ houses or wander around markets or villages.

Despite recent attempts by the Cambodian government to crack down on illegal pharmacies, these sellers fly under the radar. Most do not have any qualifications that would allow them to prescribe the cocktail of drugs they give patients, the researchers from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the University of Health Sciences found.

The invisible sellers had many misconceptions about antibiotics and dispensed them incorrectly, researchers said. Most openly admitted they sold them in response to patients’ demands, rather than medical need, leading to overprescription. They believed that antibiotics were necessary for colds and diarrhoea, and sold short courses of the drugs. They also sold antibiotics designed for humans to people wanting to give them to their cattle, chickens and dogs.

One seller said she learned about medicines during the Khmer Rouge regime and incorrectly believed antibiotics should be smeared into wounds. She said: “We break them into small pieces and pour them on wounds on our legs.”

This kind of misuse speeds up the creation of drug resistant bacteria, or superbugs, which are predicted to kill 10 million people by 2050 if no action is taken. The rise of drug resistance will make infections like urinary tract infections and pneumonia much harder to treat, and will mean it is much more risky to carry out hip replacements, C-sections and chemotherapy.

But Dr Mishal Khan, who led the research, argues that informal drug sellers are an important part of healthcare in Cambodia. She called on international health organisations and the pharmaceutical industry to do more to ensure that informal sellers have the training they need to responsibly prescribe antibiotics.

“We can’t say you can only access antibiotics with a prescription. It sounds great as a principle but there aren’t enough doctors to prescribe and trained pharmacists say only one in ten people arrive with a prescription,” she said. “There isn’t an easy solution but we need to accept the situation as it really is, not what we want it to be.”

Official pharmacies are monitored by the Cambodian government, but there are not nearly enough to tend to the country's population, researchers say

TBIJ

Official pharmacies are monitored by the Cambodian government, but there are not nearly enough to tend to the country's population, researchers say

TBIJ

The Bureau revealed last month how two major pharmaceutical companies in India persuade quack doctors to buy more antibiotics by incentivising them with free TVs and fridges. There’s an estimated shortfall of 600,000 government doctors and 2 million nurses in India, with many people depending on the more than 2.5 million quack doctors.

Khan said it “wasn’t difficult” for informal sellers in Cambodia to get antibiotics. Wholesalers would deliver antibiotics to informal sellers or they would be passed on by qualified practitioners. “Drug reps also come directly to the communities on motorbikes to promote or provide medicines,” she said.

The invisible sellers are a symptom of Cambodia’s ailing public health system, which was weakened during the Khmer Rouge regime and the country’s subsequent civil war. Medics were killed by the regime, and the lack of free government clinics now means that 70% of people visit private healthcare providers, including invisible sellers, when they fall ill.

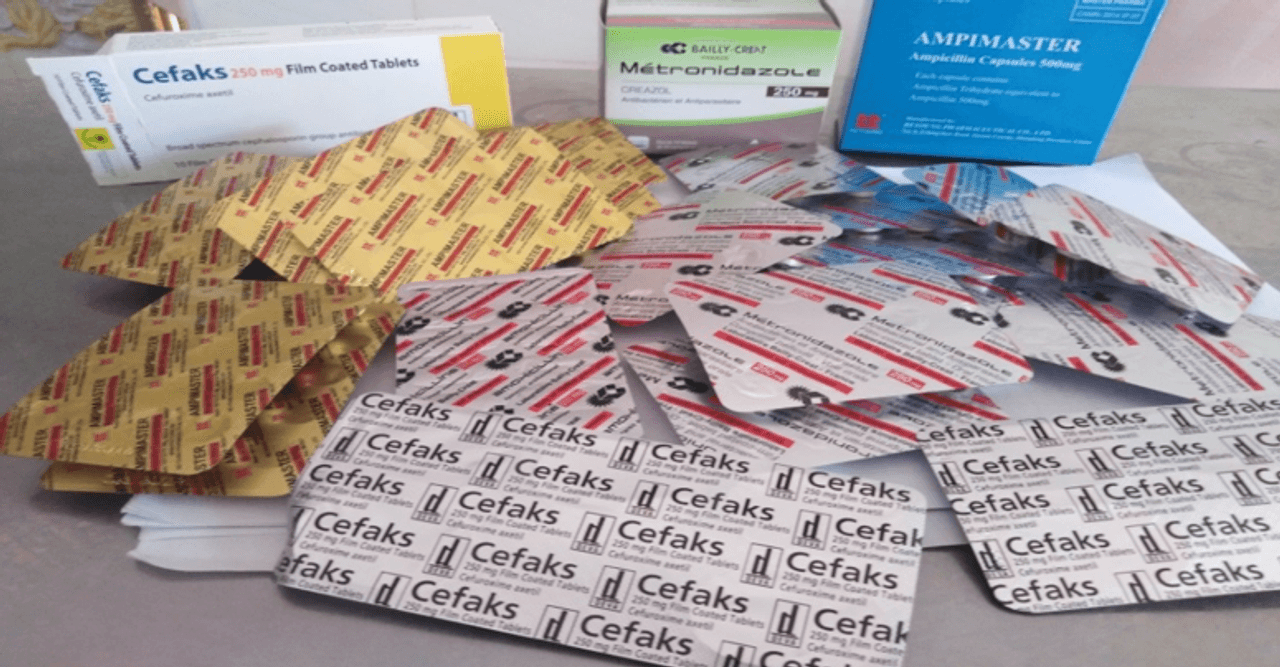

Medicines are freely available without a prescription from both licensed and unlicensed pharmacies and shops in Phnom Penh. The Bureau visited five markets in the city and were offered dozens of antibiotics without a prescription.

The country also has a problem with counterfeit medicines smuggled in from Vietnam, India, Pakistan and China. These include “substandard” antibiotics, anti-malarials and antivirals: those which do not contain enough of the active ingredient, meaning they fuel drug resistance.

Cambodia gained global attention in 2008 when malaria resistant to artemisinin, the most potent anti-malarial being used globally, was discovered in the country. Inappropriate sales of artemisinin on its own, rather than with the two other drugs it should be administered with, and the availability of substandard tablets were blamed for its spread.

The Cambodian government now keeps a list of licensed pharmacies in order to crack down on unlicensed shops, but many remain, and tackling invisible sellers is extremely difficult.

The researchers carried out community interviews in seven villages on the outskirts of Phnom Penh and found 62% of people reported using invisible medicine sellers.

They found eleven invisible sellers, five of whom were willing to be interviewed. Only one, a nurse, had training that would equip them to prescribe medicine. The others had loose links to the medical profession – a guard at a health centre, someone whose sister took a short course in pharmacy, a former pharmaceutical sales representatives and someone who stayed with doctors during the civil war – but no recognised qualifications.

They prescribed incomplete course of drugs and told patients to take a cocktail of multiple antibiotics at once. The seller who thought antibiotics should be smeared on wounds also told the researchers: “If you are very sick, you can take it [ampicillin] three times per day. If you are not that sick, you can take it for two times. I tell them that they must buy mixed drugs or the drug will only cure one symptom. You won’t cure diseases. For diseases like coughing, if you only take drugs for coughing without antibiotics, you won’t get better.”

The researchers also found doctors – who under Cambodian regulations are only allowed to stock medicines needed for emergency care – often also secretly sold antibiotics from their clinics.

Header image: Antibiotics available for sale in Cambodia. Credit: TBIJ

Our reporting on anti-microbial resistance is part of our Global Health project, which has a number of funders. Our work on superbugs (to December 2018) was funded by the European Journalism Centre. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.