JBS: The Brazilian butchers who took over the world

If you eat meat, you probably buy products made by one Brazilian company. A company with such power it can openly admit to having bribed more than 1,000 politicians and continue to grow despite scandal after scandal. And you’ve probably never heard of it.

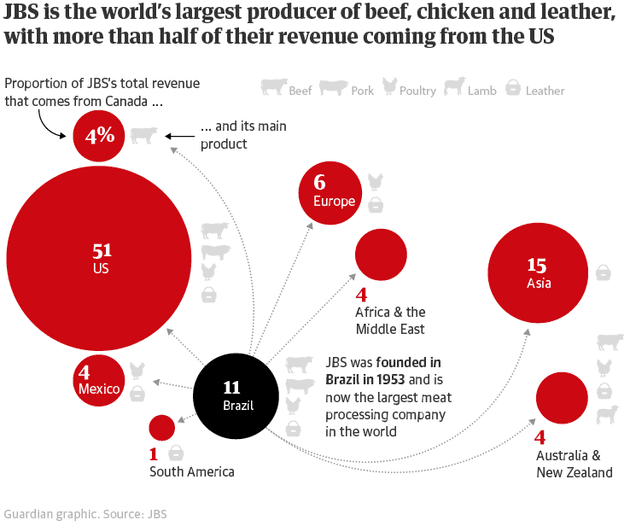

Meat is now the new commodity, controlled by just a handful of gigantic firms which together wield unprecedented control over global food production. The Bureau has been investigating the biggest of all: JBS, a Brazilian company which slaughters a staggering 13 million animals every single day and has annual revenue of $50bn.

When it comes to scandals, you can take your pick — during its rapid rise to become the world’s biggest meatpacker, JBS and its network of subsidiaries have been linked to allegations of high-level corruption, modern-day “slave labour” practices, illegal deforestation, animal welfare violations and major hygiene breaches. In 2017 its holding company agreed to pay one of the biggest fines in global corporate history — $3.2bn — after admitting bribing hundreds of politicians. Yet the company’s products remain on supermarket shelves across the world, and its global dominance only looks set to grow further.

In a two-part investigation published today, the Bureau revealed in partnership with the Guardian and Repórter Brasil that Amazon deforestation and dirty meat are very much part of how JBS has done business. Today we lift the lid on the company itself, and ask: what is the true cost of cheap meat?

A briefcase full of cash

Brazilian traders call May 17, 2017 “Joesley Day” — the date on which the power and influence of Brazil’s meat industry was exposed in all its ugly glory and gave the stock market a sucker punch.

Joesley Batista, one of two brothers who control JBS, secretly recorded President Michel Temer apparently ordering the payment of bribes to a notoriously corrupt politician who was serving a prison sentence for graft. Details of the recording, made as part of a plea bargain deal Joesley and his brother Wesley had signed arising from their own corruption investigation, were published by a leading Brazilian newspaper.

The investigation also uncovered footage of a Temer aide carrying a suitcase containing nearly $150,000, allegedly handed over by JBS. Ricardo Saud, a JBS executive, subsequently testified the company had bribed 1,829 candidates from across the political spectrum, spending almost $250m.

“It was the rule of the game. And what’s most important, corruption was on the upper floor, with the authorities,” Joesley said in an interview. At the time he was CEO of J&F Investments, the family empire’s holding company, which owns 40% of JBS.

Wesley Batista at a congressional inquiry hearing in November 2017

Andre Coelho/Bloomberg via Getty

Wesley Batista at a congressional inquiry hearing in November 2017

Andre Coelho/Bloomberg via Getty

Joesley Batista at another session of the same congressional inquiry in November 2017

Andre Coelho/Bloomberg via Getty

Joesley Batista at another session of the same congressional inquiry in November 2017

Andre Coelho/Bloomberg via Getty

The day after Joesley Day, the Brazilian stock market plunged nearly 9% in its worst collapse in nine years. Temer is thought to have only survived by upping budgets to individual lawmakers and making concessions to Brazil’s powerful agribusiness lobby.

That JBS’s activities could tank Brazil’s stock market and threaten to topple the government was a stark illustration of how far the company had come from its beginnings as a one-man operation.

JBS was founded in 1953 by Joesley and Wesley’s father, José Batista Sobrinho, who was a cattle rancher in the central western city of Anápolis. José would buy cattle from farmers to resell onto meat packers in the central western state of Goias, before opening a butchers shop with his brother.

“My older brother would buy cattle and I would slaughter it,” says José in this video telling the history of JBS. “My merchandise stood out. We only used top-class cattle ... Things took off real quick.”

A few years later, the pair saw an opportunity in the creation of Brazil’s new capital of Brasilia 125 miles away. They established a slaughterhouse which supplied meat to workers building the city.

The business quickly grew, but remained very much a family affair. All three of José’s sons dropped out of school aged 17 to manage different slaughterhouses, according to a Forbes profile, and the 1980s saw JBS expand rapidly throughout Brazil. It acquired a string of slaughterhouses and processing factories, and began exporting fresh beef — primarily cuts not widely used in Brazil. In 2007, JBS SA, its Brazilian arm, became a publicly held company.

Around the same time a national policy was introduced that propelled JBS to new heights. Brazil’s national bank BNDES began its “national champions scheme”, choosing several Brazilian companies and investing in them heavily with the stated aim of turning them into successful multinational corporations.

BNDES first invested about $580m in JBS in 2007, accelerating an international acquisition spree which saw the company buy up meat-packing businesses across the Americas, including in the US. It later bought the major Northern Ireland poultry firm Moy Park.

BNDES also invested $2bn in 2009 as JBS bought the US chicken corporation Pilgrim’s Pride. The bank today owns just over a fifth of JBS.

The national champions policy certainly paid off for JBS, which rapidly became the world’s biggest producer and exporter of meat.

In 2016 JBS made $20 billion more in food sales than the second largest meat multinational — the US firm Tyson Foods — according to the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, a US thinktank.

The journalist Raquel Landim, whose book, Why Not, charts the startling growth of JBS, described Wesley Batista as a smart manager with a close eye for detail and the more flamboyant Joesley as the risk-taker. “Joesley is very intelligent,” she said. In her opinion “he has no scruples”.

As JBS rose, Joesley bought a yacht, a Lamborghini and luxury apartments in New York and married the television presenter Ticiana Villas Boas in a sumptuous ceremony at company headquarters in Sao Paulo.

The scale of JBS’s operations today is stunning: the company employs more than 900,000 people globally, has revenues of $50bn and has customers in 150 countries. In 2018, JBS slaughtered some 77,000 cattle, 116,000 pigs and 13.6 million poultry birds every day.

“It’s a joy to see it grow,” says José Batista Sobrinho in the company video, as aerial images of thousands of cattle in feedlots play behind the subtitles. “It’s a whole new world now!”

The scandal portfolio

The secret to the company’s success, say Batistas from both generations, is that they work harder than anyone else. Others point to its network of subsidiaries in different countries, which allows it to weather storms in the market and get around particular trade restrictions — for instance when the European Union restricted Brazilian beef in 2008, JBS used its Australian subsidiary to continue exports, reported Forbes.

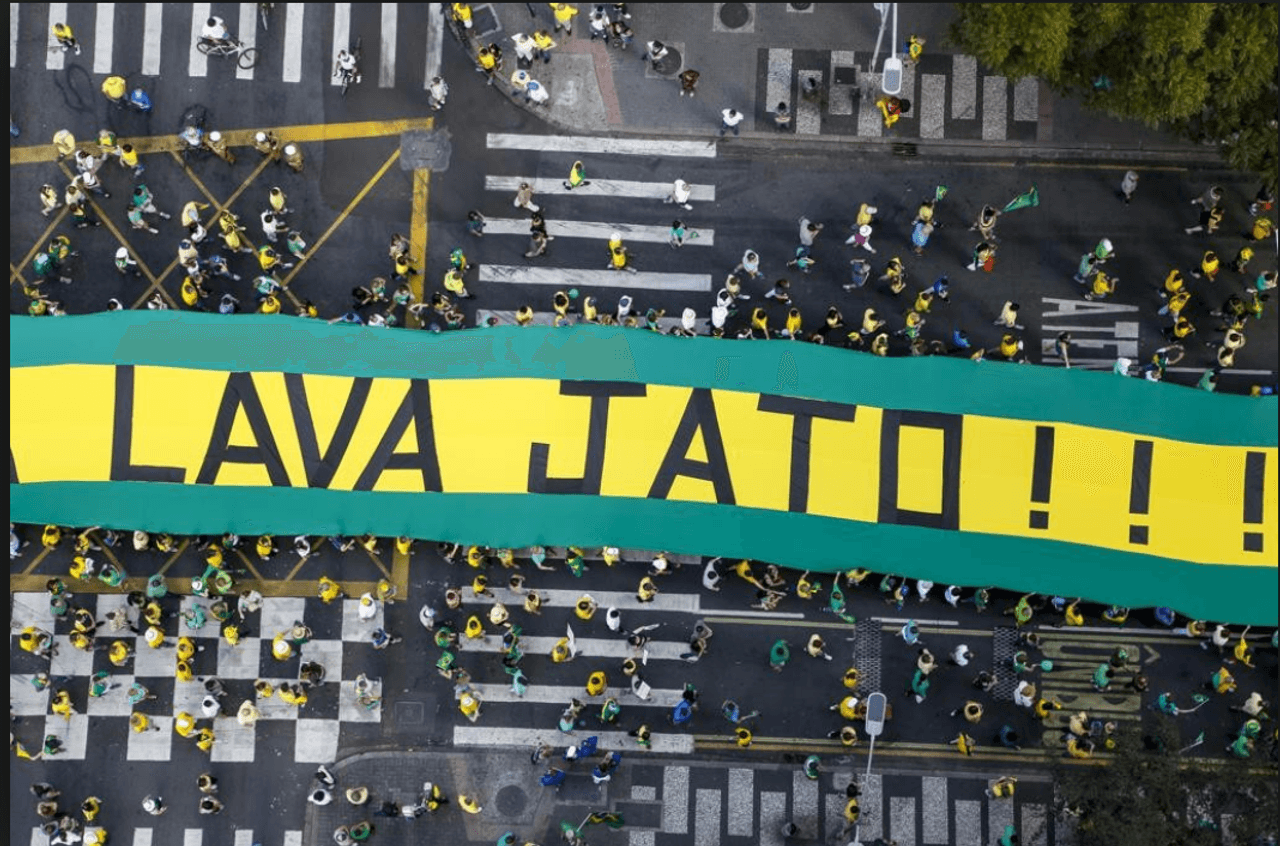

But for Brazilians, certain words may spring to mind when pondering JBS’s success: Car Wash, Weak Flesh, Capitu, Bullish. These are the operation names for massive official investigations that have taken place into the actions of JBS or its controllers. The company has been touched by allegations of scandal after scandal over the years, while its growth has continued unabated.

Corruption accusations

The scale of allegations of bribery against JBS stretches from meat inspectors to the highest office in Brazil: Temer, the aide, and the $150,000 briefcase.

Operation Car Wash was set up to investigate the bribery scandal that engulfed the Brazilian oil firm Petrobras in 2014. An astonishing network was revealed, stretching far beyond a single company and ultimately bringing down the Brazilian government.

Agriculture has long held sway over Brazilian politics — many lawmakers are farmers — but Operation Car Wash suggested that influence was backed by systemic graft. When the scandal reached JBS’s holding company, Joesley and Wesley Batista, along with five other executives, signed a plea deal in May 2017, admitting bribery of politicians.

Four months later the brothers were arrested on allegations of insider trading. In November last year, Joesley Batista was arrested again, accused of bribing officials in 2014. Even now, the Batistas’ holding company is under investigation over potential involvement in alleged collusion between executives, politicians and public servants to divert resources from a government-owned bank.

"Dirty" meat

The company has also come under fire over “dirty meat.” In 2017, JBS was caught up in an industry-wide scandal; police claimed inspectors had been bribed to allow the sale of rotten beef, falsified export and other documents, and had deliberately failed to properly inspect meat plants.

The resulting inquiry, Operation Weak Flesh, led to an EU embargo being placed on meat products produced at some Brazilian meat plants, and enhanced checks on meat and poultry imports. 60 people have been charged in connection with the inquiry — which covers much of the Brazilian meat industry — over the past two years, and investigations are ongoing.

And it's not just beef. A Bureau, Guardian and Reporter Brasil investigation published today showed millions of chickens contaminated with salmonella, including some supplied by JBS, have been exported from Brazil to Europe, including up to a million to the UK, over the last two years.

JBS said that Operation Weak Flesh had not “called into question the quality standard of its products”, and that the company followed EU standards when exporting chicken to Europe.

A Brazilian chicken factory

Shutterstock

A Brazilian chicken factory

Shutterstock

"Slave labour" allegations

In 2017, an investigation by the Guardian and Repórter Brasil found JBS had bought beef from a farm that was under investigation by Brazilian prosecutors for using workers in conditions described as being like “modern-day slavery”. Documents said police had found men forced to live in conditions described as inhumane and degrading, with inadequate shelter, toilets or drinking water.

Waitrose pulled JBS-supplied corned beef off the shelves following the story. JBS said it immediately stopped buying beef from the farm in question following the police raids and “does not buy cattle from any farms which have any association with slave labour, as listed by the Brazilian government”.

Animal cruelty

Also in 2017, an investigation by the Humane Society of the United States claimed undercover researchers had seen chickens being punched and beaten with iron rods at a farm and an abattoir contracted to Pilgrim’s Pride, one of JBS’s subsidiaries. Another animal rights group, Mercy for Animals, released video footage the following year that it said showed workers at a JBS supplier beating piglets and ripping off their testicles without anaesthesia.

JBS said in a statement that it suspended shipments from that pig supplier site and had started an investigation, and that it did not condone or participate in any type of animal abuse. Pilgrim’s Pride also launched an investigation, suspending supply from at least one of the farms.

Price fixing

In recent years, multiple lawsuits have been filed in the US accusing JBS and other major meatpacking firms of colluding to fix prices. The US opened a criminal investigation into the allegations against the JBS-owned Pilgrim's Pride and other poultry producers late last month.

Last year the country’s two biggest food distributors, Sysco Corp and US Foods Holding Corp, claimed major poultry producers had deliberately cut off the supply of chicken in order to drive up wholesale prices. It was the third lawsuit making such allegations in two years.

And in April this year, a lawsuit filed by independent cattle ranchers accused JBS and three other major US beefpackers of colluding since 2015 to drive down the prices they paid farmers for their meat.

Cattle grazing on deforested land in Brazil

João Laet

Cattle grazing on deforested land in Brazil

João Laet

Deforestation

JBS has repeatedly been accused of buying cattle raised on illegally deforested Amazon land. In 2017 the company was fined $7.7m by Brazil’s environmental regulator for buying cattle from ranchers operating on blacklisted land. Greenpeace has released multiple reports making similar allegations, which the company has always vigorously denied.

Our latest investigation shows companies illegally raising cattle on deforested land are still supplying JBS. Reporters visited a farm and saw cows grazing in embargoed areas at a ranch belonging to a company known as Santa Barbara, and saw official state documents confirming cattle from that ranch were delivered to sites which supply JBS slaughterhouses.

In response, JBS said that 99.9% of its cattle purchases meet its socio-environmental criteria. It also said that it was working to implement “a new procedure to cover all links in the supply chain” and stop the use of “cattle from illegally deforested areas”.

The UK connection

After every scandal regulators have attempted to take action against JBS, but nothing seems to stunt its growth. The EU has in the past temporarily restricted Brazilian beef; JBS products have occasionally been pulled from supermarket shelves. But when one arm of the business is affected, another fills the gap. If you live in the UK, there probably isn’t any JBS beef in your freezer, but check your chicken.

Like JBS, Moy Park is not a name consumers will recognise, yet it is one of Britain’s biggest food companies and supplies more than a quarter of the chicken we eat.

In a story echoing that of the Batistas, the company started out as a small farming enterprise in the 1940s. But over the past decade an aggressive growth strategy has seen it establish a near monopoly on Northern Ireland poultry production.

By 2015 the company was slaughtering five million birds a week. That same year it was bought by JBS for £900m, which took over an ambitious programme of farm construction across the UK.

With investment of about £200m, Moy Park’s dramatic expansion plan involved building hundreds more poultry houses in Northern Ireland and other parts of the UK.

The extra farms enabled another surge in production. Last year the company posted record figures of six million birds slaughtered each week, hailed as a milestone by company executives.

The number of intensive poultry megafarms, defined as those housing 40,000 or more birds, in Northern Ireland more than doubled between 2011 and 2017. There are also almost 50 units with more than 80,000 chickens. Many of these megafarms supply Moy Park.

The company is now Northern Ireland’s largest private sector business, with a reported turnover of £1.5bn in 2017, supplying virtually all of the major UK supermarket chains, as well as McDonalds and KFC.

Yet Moy Park has itself not been immune to scandal.

Since 2015 Moy Park has been fined more than £1m for a series of infractions, including subjecting chickens to “unnecessary pain and distress”, failure to pay workers the minimum wage, and unsafe work systems that led one employee to suffer life-changing injuries in an accident.

There’s vast wastage, and at abattoirs birds arrive unfit for human consumption. Last year, in slaughterhouses across Northern Ireland, almost 3 million chickens and other birds were plucked off production lines by meat inspectors. Due to its dominance of the market, a significant number of them will likely have come from Moy Park farms.

Diseased, emaciated or injured — many suffering fractures, bruising or dislocations — dead on arrival, contaminated, or damaged by machines during slaughter, the birds were disposed of. From 2016 to 2018, almost 8 million birds were discarded this way.

As recently as last week, Moy Park was accused of keeping animals in “horrifying conditions”, after secretly filmed footage at three Moy Park farms in Lincolnshire showed chickens that were lame, struggling to breathe and surrounded by dead birds.

Responding to the recent story, published by the Guardian, a company spokesperson said: “We have a zero-tolerance attitude toward anything that jeopardises the health and welfare of our birds and we are fully investigating these allegations.”

Corporate meat

Though it is by far the biggest, JBS is not the only meat giant. With global meat consumption expected to skyrocket in the coming years, and with some estimates suggesting that the combined meat, poultry and seafood industries globally could be worth $7 trillion by 2025, meat has become the new global commodity, joining such staples as oil, corn, soya, steel and gold in keeping the world moving.

Yet while corporate dominance in other key agri-commodity markets — grain, seeds, chemicals — is better understood, allowing for enhanced scrutiny and public debate, the same is not true of the meat sector. Many of the companies controlling the trade are little known outside of industry circles, often obscured behind brand names or supplying raw ingredients to supermarket chains, fast food outlets or wholesaler catering firms.

Ranchers in Brazil

João Laet

Ranchers in Brazil

João Laet

In the UK, just a handful of companies — of which many are subsidiaries of overseas corporations — now control large swathes of the meat sector: Dunbia, Dawn Meats and ABP dominate the beef sector. 2 Sisters Food Group, Faccenda, Cargill — as well as Moy Park — run the show on poultry.

Globally, it’s a similar picture with a clutch of multinational firms doing much of the rearing, slaughter, processing and supplying of red meat and poultry internationally — among them Tyson, Smithfield Foods, BRF, Vion, Cargill, and of course JBS.

With a spiralling global population, a climate emergency and widespread hunger in large parts of the world, what we eat, how we produce it, and — crucially — who produces it, matters. The supply of safe food, free from disease, sustainably produced and fairly priced, is vital for both food security and public health.

JBS began as a local butcher’s shop; now its beef travels thousands of miles from Brazil to UK supermarkets. That journey clouds the link between farm and plate and makes it almost impossible for the average consumer to understand where their food comes from — and how high a price the planet is paying for their cheap meat.

Make change possible

Investigative journalism is vital for democracy. Help us to expose injustice and spark change

Click here to support usOur Food and Farming project is partly funded out of Bureau core funds and partly by the Hollick Family Foundation (for 2020) and The Guardian. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.