How ammonia is killing off the countryside

To the untrained eye, the ancient woodland of Gregynog in mid-Wales seemed in good condition. It was late spring and the trees were heavy with green leaves. The grass was lush and the birds were noisy. Yet on closer inspection, there was a problem.

“Look at this dead lichen overgrown with algae.” Sam Bosanquet, a plant ecologist with the Welsh environment agency Natural Resources Wales (NRW), pointed to one of several coral-like growths on the branch of a tree in the middle of the woodland.

These lichens — groups of organisms that grow on bark or rocks and take nutrients from the atmosphere — should be a pale olive colour, but several were largely consumed by a lurid green. It was algae. “We are in the heart of a designated site of special scientific interest, where the lichens should be healthy,” he said.

The root of the problem, he said, was ammonia.

The gas emanates from animal excrement on livestock farms, several of which surround the site, and poses a problem for both human health and the environment.

While some of the gas mixes with industrial or vehicle pollution away from farms, creating “particulate matter” harmful to humans, the rest is deposited in the rural environment as nitrogen. It harms some plant species and boosts others as a fertiliser, damaging the balance of ecosystems and putting biodiversity at risk.

“We are very much in the transition between Gregynog being a clean-air area to an ammonia-polluted area,” Bosanquet said. The changes underway at the site, protected for its rare lichens and insects, are reflective of a wider problem: nearly 90% of sensitive habitats in Wales and nearly two thirds of those across the UK were exposed to harmful levels of nitrogen from 2014 to 2016, according to research by the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology published by Defra.

The problem is only getting worse. Ammonia is the only pollutant for which emissions are rising: Defra figures suggest an increase of more than 10% between 2013 and 2017, to 245,000 tonnes. The department says that nearly 90% of the UK’s ammonia emissions come from agriculture, and that the sector is the main culprit for the emissions rise.

“Ammonia is causing dramatic landscape-scale impacts on virtually every terrestrial ecosystem,” said Bosanquet. Studies across the UK and Europe have highlighted how nitrogen from agricultural ammonia is affecting biodiversity: grasslands are losing species, which can hit pollinating insects, and fungi that help trees and other plants to grow are being killed off.

The ammonia pollution at Gregynog — which, according to Bosanquet’s study undertaken in 2017, has affected lichens on every tree in the woodland — could have dire knock-on effects. The full, coral-like lichens that are sensitive to nitrogen, and are therefore dying off, usually provide good habitats for spiders and other invertebrates. These in turn provide food for woodland birds, such as woodpeckers and nuthatches. Lichens and similar organisms can also absorb half of all rainfall in forest ecosystems, preventing erosion and flooding as well as storing water that is later released in drier periods.

The UK government has recently woken up to the problem and launched a Clean Air Strategy addressing ammonia, among other pollutants, in January this year. The report said the government would start regulating ammonia reduction measures in farming and experts have generally seen it as a step in the right direction, but it was vague on who or what will fund these often expensive measures, aside from a “future environmental land management scheme”.

Simon Bareham, NRW’s principal adviser on air quality and biodiversity, said that the threat agricultural ammonia posed to ecosystems was unprecedented. “If we don’t do something about it we risk losing some of these internationally important [ecological] communities that we have and have hung onto since the last ice age,” he told the Bureau. “In the short term, this poses one of the biggest threats to biodiversity that I’ve come across in my working career of over 30 years.”

Slurry: "It stinks, it's absolutely dire."

Livestock farms are the main source of ammonia pollution across the UK, contributing 65% of all emissions, and cattle operations are the worst offenders. Cattle farmers face few rules concerning their ammonia management, although the government plans to close this loophole by 2025.

A rise in UK cattle numbers is one of the key factors behind the recent climb in ammonia emissions, according to Professor Mark Sutton, an ammonia specialist at the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology (CEH) in Edinburgh. Another is arable farmers using cheap fertilisers made of urea, a chemical compound found in urine that breaks down into ammonia.

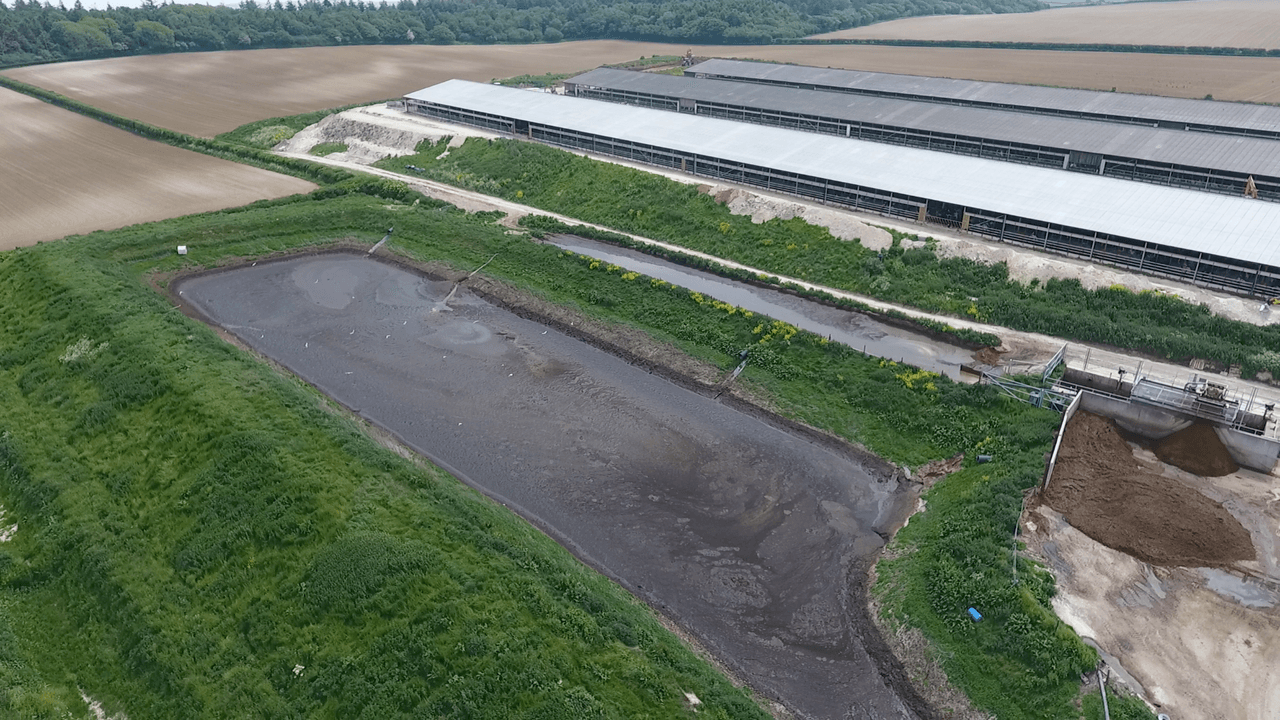

Intensive housed systems for cattle and pigs tend to produce more ammonia because the animals’ urine and dung usually mix together in their sheds, producing slurry, according to Sutton. This cocktail, which is more toxic than the substances are separately, emits ammonia at every stage of its use: when it is created, when it is stored in uncovered slurry “lagoons” and when it is sprayed onto fields as a fertiliser. In contrast, when animals graze outdoors, their urine is absorbed by the soil, producing lower emissions.

Cows produce slurry, a mixture of faeces and urine, when they are kept indoors

TBIJ

Cows produce slurry, a mixture of faeces and urine, when they are kept indoors

TBIJ

The Bureau spent two days in the Hartland Peninsula in North Devon, one of the UK’s major dairy regions, to meet both farmers and their neighbours living with slurry.

In the village of Hartland the strong, close odour hit our nostrils with some force and seemed to cling to the air. Multiple slurry tankers were spotted on the surrounding lanes and we watched one spraying the liquid manure onto a field. At the end of the day we carried the smell home with us on our clothes.

People who had lived in the area for decades said they were having to endure the stench of freshly spread slurry more frequently. “It used to be like, you go out in the country and it’s a beautiful day and you take a deep breath of fresh air, and then you could smell the different herbs, the different grasses, and what’s flowering,” said Sarah Macdiarmid, a gardener who has lived in the area since 1990.

“Not anymore. Most days when you go out, you’ve got a brief window and if [the weather] is fine, they’re going to be spraying. And it stinks, it’s absolutely dire.”

Another woman, who did not wish to be named due to local tensions over slurry, said: “The farms have got so big and the cows are permanently housed. There’s just so much more slurry now.”

Her partner added: “When it’s bad you can’t open your windows.”

Although in Hartland residents’ complaints focused on the smell, a study into the potential human health impacts of airborne emissions from intensive farms last year raised concerns about their wider consequences.

The report, published in March 2018, stated that “biological emissions from intensified livestock farming may have the potential to impact human health”. It added that emissions were likely to increase as more farms switch to intensive methods, which could pose a threat to health in nearby communities.

The price of pollution

Farmers around the Hartland Peninsula say slurry and its ammonia emissions are a result of supermarkets pushing down food prices and forcing them to intensify.

One farmer who had sold off his 400-strong dairy herd but kept 60 beef cattle said that mixed farming — promoted by many as more sustainable than keeping just one or two species or crops — would never become widespread while consumers still expected cheap food.

“Thousands of milk producers have gone out of business this year and the ones that are left will just get bigger and bigger,” he said. “I would hate to be the next generation of farmers unless something drastically changes.”

Andrew Opie, the director of food and sustainability at the British Retail Consortium, told the Bureau that retailers know how important agriculture is to emissions reduction. “Retailers have built up long-term relationships with their suppliers and know farmers need a fair price to improve their businesses [...] The industry has many dedicated farming groups where retailers share best practice in environmental improvement,” he said.

However, farmers complain that what they receive for their products are not enough to pay for the expensive measures to reduce ammonia emissions recommended in the government’s Clean Air Strategy, such as covering slurry lagoons and injecting it into fields instead of spraying.

One dairy farmer with 480 cows said he had installed a cover on his lagoon for environmental reasons, but at a cost of £35,000, he had only been able to do so with a grant. “If I got 3 or 4p more [per litre] for my milk it would be cost effective,” he said.

A slurry tanker

TBIJ

A slurry tanker

TBIJ

Defra offers a few grant schemes in England for lagoon covers and slurry injecting, but they do not apply nationwide. There are no grant schemes in Wales or Scotland and Northern Ireland’s small scale trial grants are under review.

“I would like to see covers and proper storage at the farm,” said another dairy farmer, whose 220 cows graze for half the year. He explained that without enough storage space for slurry — which is expensive to build — he sometimes has to spread the fertiliser on fields in wet weather, when it can run off and pollute watercourses. “The government should help with that.”

A chicken and egg problem

While cattle and pigs tend to produce more ammonia with more intensive farming systems, the opposite is often — surprisingly — the case with chickens and hens. Birds do not urinate so the ammonia they produce comes from their faeces alone. The more they wander and excrete outside in free-range systems, the more opportunity there is for the ammonia to escape into the atmosphere.

This is causing a real headache in Wales, according to NRW, where poultry production has boomed in the last decade. Numbers from the Campaign for the Protection of Rural Wales suggest there are now more than 7 million birds in Powys, up from 1.7 million in 2010; the group says over 3 million are free-range.

“ ‘Free-range’ used to be going to a farm, a few dozen hens, picking up some eggs,” said Simon Bareham from NRW. “But over the last eight or nine years we’ve seen these free-range units get bigger and bigger, from a few hundred to a few thousand to tens of thousands.”

All devolved administrations in the UK regulate what they consider to be “intensive” poultry operations — those with more than 40,000 birds — but Bareham explained that these units were not the problem. “They can be controlled through fans and emission controls, it’s actually — believe it or not — the free-range issue that’s the biggest issue.”

In 2015 officials at NRW noticed that free-range poultry farms were a major source of ammonia pollution. While big, they tend to fall below the 40,000 mark and therefore do not require an intensive farming permit, skirting stringent regulations on managing ammonia emissions.

Bareham and his team commissioned a study of poultry-related ammonia emissions in Powys after a local objected to an 80,000-bird, non-free range unit that would have been regulated. They found 13 smaller poultry farms nearby. “Those that appeared off the radar, away from view,” he said.

The team calculated each farm’s ammonia footprint and discovered that several 12,000-bird free-range units were each producing more ammonia than the 80,000-bird farm would have.

“This is a landscape that has escaped a lot of the ravages of the industrial pollution from the Industrial Revolution,” said Bareham. “We’re […] then having these very high concentrations of ammonia that result from these units just being dotted round willy nilly in the countryside.”

The Bureau newsletter

Subscribe to the Bureau newsletter, and hear when our next story breaks.

The existing farms were unregulated, meaning they only needed permission to operate from local authority planning officers. The team at NRW realised many planning officers were not considering the cumulative impacts on pollution from existing farms when considering new proposals.

NRW released new guidance encouraging planning officers to consider the combined ammonia impact where farms already exist, especially where new farms are proposed near potentially sensitive natural habitats.

While some could say NRW’s approach merely relocates ammonia emissions away from ecologically sensitive sites, rather than reducing the total, the team said it was the first step in a broader re-examination of the ammonia problem.

Some farmers are already making progress on capturing ammonia and reducing the overall output. Trees can be planted strategically in and around free-range poultry enclosures or near livestock sheds to capture ammonia emissions, as well as other greenhouse gases.

“There are of course multiple benefits for planting trees in the landscape — carbon sequestration, screening livestock buildings, welfare, ammonia capture, flood risk, water quality to name but a few,” said Dr Bill Bealey, who is part of the team developing the tree-planting approach at the CEH in Edinburgh.

“We already have a fair bit of interest in this tree planting measure,” he added. Woodland enclosures can also offer chickens space to roam with shelter from bad weather and protection from predators, giving the birds a higher quality of life. “Many egg producers are planting trees around their barns to enhance free-range animal welfare, deliver better egg quality and reduce hen mortality.”

Our Food and Farming project is partly funded out of Bureau core funds and partly by the Hollick Family Foundation (for 2020) and the Guardian. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.