Revealed: The thousands of public spaces lost to the council funding crisis

The local government funding crisis has become so dire that councils are being forced to sell thousands of public spaces, such as libraries, community centres and playgrounds.

In a double blow to communities, some local authorities are using the money raised from selling off buildings and land to pay for hundreds of redundancies, including in vital frontline services.

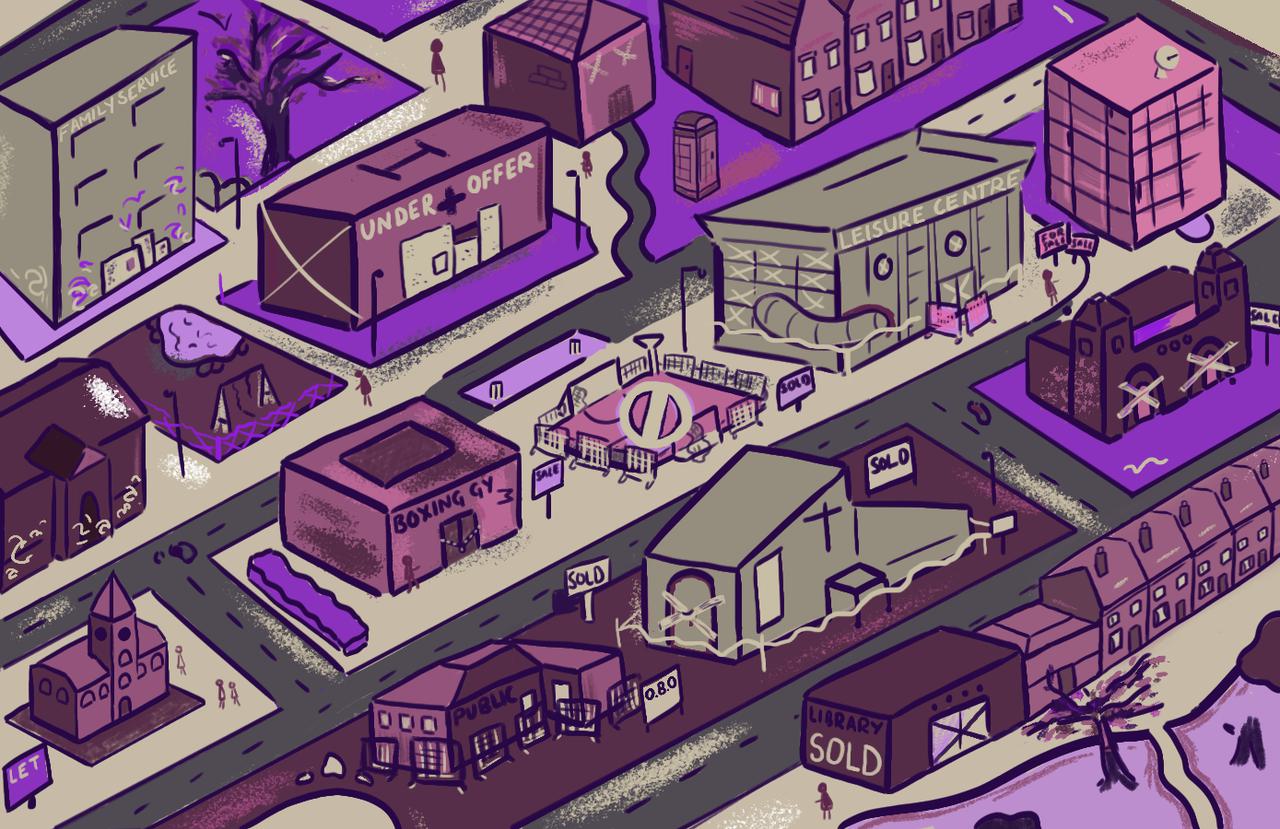

In a major collaborative investigation with HuffPost UK and regional journalists across the country, the Bureau has compiled data on more than 12,000 public spaces disposed of by councils since 2014/15. Our investigation found that councils raised a total of £9.1 billion from selling property.

The findings lay bare the spiralling impact of eight successive years of austerity, leaving services shut and buildings closed. Councils have been forced to take ever more desperate measures to stay in the black as their funding from central government has been cut by about 60% since 2010.

“This is an absolutely ridiculous way to do business,” said Khalid Mahmood, MP for Perry Barr in Birmingham, where the council has sold off land and buildings and spent the proceeds on making workers redundant. “We should never have been selling the land that we have inherited from our forefathers [...] It just takes the future away from our children and grandchildren to come and that is really devastating.”

What has your council sold? Enter your postcode into our interactive map to find out.

Our investigation also discovered a link between the sell-off of public assets and a sharp rise in redundancies at some councils, following a new government policy which gave local authorities more freedom over what they could do with their money.

Previously, money made from selling public assets could only be used to fund the cost of buying new ones. In April 2016, the then Chancellor George Osborne relaxed the rules to allow local authorities to spend the proceeds on cost-cutting measures, such as sharing back-office functions with other authorities, investing in new technology or other reforms which have upfront costs but reduce spending in the long-term.

Freedom of Information requests submitted by the Bureau found 64 councils in England have spent a total of £381 million made from property sales using the new freedom since the policy came into effect. Almost a third of that - £115 million - was spent on making people redundant.

Our investigation revealed a clear trend - over the three years since the rules were relaxed, the average number of redundancies was 75% higher at councils that made use of the new spending powers than at those which did not.

In Bristol, the number of council workers made redundant jumped ten times from 39 the year before the new rules were introduced to 401 the year after. The council paid for many of the redundancies by using proceeds from the sale of assets, which that year included a historic library.

“If given the choice – would you consider selling a disused council building to raise funds to deliver a balanced budget – or would you retain that asset for potential future use but instead cut adult social care, or raise charges for care packages?” asked the director of the County Councils Network Simon Edwards.

“Put bluntly, these are some of difficult the decisions facing councils every day. Local politicians do not go into public service to slash and burn or make valued staff redundant, let alone sell assets to do this. But this is the financial reality of years of funding reductions and rising demand,” he said.

Blame could not be laid at the door of local government decision makers, said Labour deputy leader Tom Watson.

“Council budgets have been cut to the bone by almost a decade of Tory austerity,” he said. “As a result, we’re seeing cash-strapped councils taking desperate measures to balance their books.

“Selling public buildings and spaces was a false economy that leaves our communities poorer… responsibility for these cuts lies firmly at this government’s feet. They should take urgent action.”

Much more than just a building

When it comes to the loss of community spaces, boxing coach Mark Holt does not hold back. After all, he has first hand experience, not once but twice.

“The council is closing so many youth centres and they wonder why there are kids out on the streets stabbing each other,” said Holt, 51, who has dedicated his life to family-run Nechells Amateur Boxing Club.

For almost 60 years the club was based in Nechells Green Community Centre, in the Nechells district of inner-city Birmingham. In 2016 the Holts - Mark, his dad Derek, 77, and his uncle Ernie, 81 - were told by the council the club would have to vacate the building so it could be auctioned off.

“The council called a meeting to say the building wasn’t making enough money so it was going to be sold,” said Mark.

The club, which has produced a string of champions and attracts around 50 members per session, was eventually relocated to Newtown Community Centre, which is where they currently train three nights a week.

The arrangement is temporary because the building, where legendary rock band Black Sabbath first rehearsed, is also being sold by the council.

Members of Nechells Amateur Boxing Club spar as others watch

Photo by Alex Sturrock

Members of Nechells Amateur Boxing Club spar as others watch

Photo by Alex Sturrock

Boxing coach Mark Holt, right, says the club is a vital community space

Photo by Alex Sturrock

Boxing coach Mark Holt, right, says the club is a vital community space

Photo by Alex Sturrock

“We’ve been told we’ve got to leave again so we’re in the process of trying to get our own unit,” said Mark.

“It’s destroyed my uncle. He doesn’t sleep. We don’t just run a boxing club, we go to shows all around the country with our lads. We keep kids off the streets.”

In February, Nechells Green Community Centre sold at auction for £1.3 million, more than three times the guide price. It is the latest publicly-owned property to be sold by Birmingham City Council, in a list which includes care homes and other community centres.

During the last three years the local authority has made extensive use of the new freedoms around sell-offs, spending £49 million raised from assets on making reforms or cuts to services - more than any other local authority. Spending funded with this money includes a £12 million investment in a new IT system, £1.6 million on changes to its waste service and a staggering £23 million on redundancies, of which there have been nearly 1,000 since 2016/17.

The council’s workforce has halved since 2010 - and just last week, plans to cut another 1,095 jobs were revealed.

“Local government has never been so wilfully neglected by Whitehall and the choices we are having to make get tougher every year,” council leader Ian Ward said. “Inevitably that impacts on communities across the city.”

The financial challenges are being felt on the ground. As well as Nechells Green Community Centre and the impending loss of Newtown Community Centre, the council also sold Phoenix Community Centre and Square Club Community Centre after the spending rules were relaxed.

In total the council disposed of 167 buildings or plots of land between April 2016 and July 2018, according to our FOI. The council refused to reveal the prices or who the assets were sold to.

The Labour-run authority proposed a controversial change to its constitution which would raise the threshold under which council officers can approve sales behind closed doors from £1 million to £5 million. The idea has been temporarily shelved after opposition from Conservative councillors.

“It’s completely undemocratic and it’s part of the reason why Birmingham has so many problems, because there isn’t proper oversight of what is being done,” said Robert Alden, leader of the Conservative group on the council.

“The council has to be very careful about how it uses its assets because once you’ve lost them, they’re gone. With many of the assets the council is selling they’re getting a short-term benefit but not looking at the long-term revenue impact.

“Part of the savings the council is having to make is because they have disposed of the income generating assets without replacing the income source. So it has ended up filtering through and hitting front line services.”

Zain Ali, 20, who's boxed at Nechells since he was nine years old, with club founder Ernie, 81

Photo by Alex Sturrock

Zain Ali, 20, who's boxed at Nechells since he was nine years old, with club founder Ernie, 81

Photo by Alex Sturrock

Jobs lost as well as spaces

Birmingham was the biggest spender we found in terms of funding redundancies through selling assets. But Bristol provides the starkest example of how relaxation of the rules around sell-offs has in some cases led to soaring job cuts.

In the financial year 2015/6, when local authorities were only allowed to use money from selling assets in order to buy new ones, Bristol City Council made 39 people redundant. The following year, when local authorities were free to spend sales money on “service reform,” the council made ten times as many redundancies. Our investigation found that £5.3 million raised by selling assets was spent on making people redundant that year.

Councils including Leeds, Sunderland and Telford and Wrekin also made significantly more layoffs than usual once they were able to use the proceeds from selling public buildings and land to fund them.

Five local authorities in London spent money from selling assets on making people redundant, our investigation found. Haringey spent £8 million this way and job losses increased 70%. Assets sold by the council during this period included two community centres to a property developer.

Onay Kasab, London regional officer for Unite, was unaware his members’ redundancy packages had been paid for with the proceeds of community asset sales.

“It’s shocking and appalling,” he told the Bureau. “We are calling on councils to stop making job cuts and to stop cutting services. They don’t have to be selling off public land. They need to be lobbying the government for extra money, not selling off the few assets they have left. It’s ludicrous.”

A double blow to communities

Our investigation found services for society’s most vulnerable people have often been twice hit by council sell-offs. In the last three years, Staffordshire County Council has sold four care centres including residential homes for the elderly and day facilities for adults with disabilities. During the same period, it spent £843,000 made from selling assets on making people redundant, with two thirds of the job cuts made in social services.

Janet Convey and her family have sharply felt the effect of the cutbacks. Her son Paul, 49, who has complex learning disabilities, used Kidsgrove day centre from the age of 21 until it was closed in 2015.

The facilities had included two sensory rooms and disabled toilets that the parent-teacher association had paid for through years of fundraising. The building was later sold to Bluebell School Ltd, a private school, for £395,000 in 2016/17.

“It was devastating,” Mrs Convey said. “People might say there are private providers and various other opportunities in the community, but nothing can compare with what is provided by a fully authenticated day service run by a county council.” Her son now attends a private service set up by two carers, run in a community hall.

Dave Bailey’s son Stuart, 52, has also personally suffered from council sell-offs. He lives at home with his parents, who help him to dress and cook each day, and used another day centre for over 30 years until it was closed in 2016.

The centre had provided a crucial sense of community, said Bailey. “They have friends at their level. The parents have someone to talk to.”

Chase Day Services was sold by the council to D&G, a developer, for £600,000 in 2017/18, and remains empty. Staffordshire Council told the Bureau that the centres were not closed so that they could be sold off.

Deputy Leader of the council Alan White, said the closures were part of a reform of social care which meant “more people having choice and control over their own care, and accessing the many different opportunities available to them.

“Rather than allowing buildings to stand idle or fall into disrepair, we are committed to maximising the return for taxpayers and breathing new life into sites to support health projects, housing and the local economy where possible.”

The Bureau found a number of councils where adult and children’s social care departments suffered job cuts as public buildings and spaces were sold. Rotherham, which was shamed by a child sexual exploitation scandal in 2012, was one example. It put £3 million from asset sales towards redundancies, with 70% of the jobs being lost in social care.

Nowhere to turn

Councils are being forced to do whatever they can to stay afloat and keep services running, following eight years of increasingly harsh cuts to their budgets. Historically, one of the main sources of funding for local authorities has been a grant from central government - but that funding has been cut by two thirds since 2010 and by next year will be almost completely phased out.

Government policy aims for councils to become fully self-financing using their income they get from council tax and business rates - but local government representatives warn that the amount many councils can raise that way is already far less than what they need, and that their bills will only get higher as demand for their services grows with an ageing population.

Northamptonshire County Council became the first major casualty of the funding crisis when it collapsed last year, suffering a £70 million shortfall in its budget. It was taken over by government-appointed commissioners and had to make “radical” cuts including to children’s services, road maintenance and waste management.

A report last March found the council had sold off buildings and spaces simply to balance its books, instead of using the money to fund measures that would have reduced costs over the long-term. Using the proceeds from asset sales to plug gaps in finances is strictly prohibited under the government rules except in exceptional circumstances.

This short-termism was a significant factor in the council becoming the first in nearly 20 years to effectively go bankrupt and the findings of the investigation were so scathing that Northamptonshire was barred from using its property sales to support its budget again. That decision was overturned in November amid concern the authority would again be unable to balance its books.

Lack of awareness

Councils selling public land and buildings to fund cost-cutting measures - a policy called the “flexible use of capital receipts” - must in the government’s words, “demonstrate the highest standards of accountability and transparency.” This means producing annual reports detailing the amount of money being spent, the projects funded and the savings targets set.

Our investigation found those standards were not always being met, preventing proper scrutiny and denying the public the chance to properly debate the decisions about what is sold and what the money is used for.

Two thirds of councils are not fully adhering to the rules around the data they have to publish about the land and buildings they own, we found. Additionally, about 30 refused all or most of the Bureau’s FOI request which asked for details about what assets they had sold. Another 36 councils responded to the request but withheld how much the properties were sold for and who they were sold to.

There is also a lack of information about how the funds are being channelled into redundancy pay-outs. Of the 39 local authorities which told us they had used proceeds from selling land and buildings to pay for redundancies, a third had not included that information in the financial data submitted to the government at the start and end of each year.

And while most councils are publishing the transparency reports required under government guidelines, those reports do not have to include details of which assets were sold.

During our reporting we also encountered a lack of awareness about what was happening from people and organisations directly connected to the issue. None of the union representatives we spoke to knew councils had funded redundancies by selling public buildings and spaces.

The cross-party Public Accounts Committee (PAC), which oversees all government expenditure, recently completed a report into council finances, accusing the government of being in a state of “denial” - but the report made no mention of the fact councils were selling off community assets.

When contacted by the Bureau, Meg Hillier, chair of the committee, said the sale of public spaces did not fall under the scope of the report’s research. Much more scrutiny was needed in terms of how the relaxed rules on spending were playing out on the ground, she said.

“Government needs clear oversight... councils might like the freedom it gives them but it’s difficult to resist when they have no other options and there could be perverse outcomes as a result.

“What happens when councils need to build more housing or open more schools but they don’t have the space to build in? They are stacking up problems for the future.”

The new rules were initially introduced for a three-year period but were later extended until 2021. Given councils’ options are extremely limited, it is likely any attempt to introduce greater regulation would meet with stiff opposition.

Yet as all central government funding is withdrawn next year, the financial pressure on councils is only going to increase. As that happens, more could turn to selling off public spaces.

“Councils are in a precarious financial position after years of budget cuts and uncertainty about how they will be funded post-2020,” said a spokesperson for the Local Government Information Unit think tank.

“They welcome further financial flexibility but as it stands councils have a limited range of levers at their disposal.

“We are in danger of forcing councils to sell off the family silver to stay afloat.”

Concerned? What can you do?

Share our stories We are sharing a series of stories on this topic - please share these with those in your community - via email, social media, or on a community forum! Join us by using hashtag #SoldFromUnderYou.

Use our map as evidence Explore our interactive map to find out what’s been sold off on in your local area - if you’re concerned about the results you can write to your council and your MP to raise the issue. Or if you have information about a particular building or space that has been sold off, let us know.

Safeguard the future If you know of local buildings or spaces under threat, you can tell Locality, who coordinate #SaveOurSpaces, and who also advise what communities can do to save public spaces.

All illustrations by Hannah Eachus

Our reporting on local power is part of our Bureau Local project, which has many funders. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.