How clean water can be the most powerful weapon against superbugs

Above one of the doors of the Mirigu health centre in the Upper East Region of Ghana, the words "labour ward" are written in black marker.

In a cramped room no more than a few metres wide, midwife Felicia Akansi delivers about 15 babies every month, and staff members treat hundreds of patients for conditions as minor as a cough to seriouus diseases like malaria.

The health centre has been busier than ever since it got running water last year. There can be severe shortages of water at rural health facilities like this - but the same cannot be said for antibiotics.

Even facilities without running water on site have a steady stream of antibiotics to give to patients, with the drugs readily available and widely used to treat infections often spread by unhygienic conditions.

The more antibiotics are used, the less well they work - but the more they are again prescribed.

It's a vicious cycle that means bacteria are growing ever more resistant.

Midwife Felicia Akansi delivers about 15 babies every month with limited resources.

Photo by Ben Stockton/TBIJ

Midwife Felicia Akansi delivers about 15 babies every month with limited resources.

Photo by Ben Stockton/TBIJ

About half of patients in Ghana's biggest hospital are prescribed antibiotics, compared with a third in hospitals in Europe.

Although data is limited for rural health care facilities like Mirigu, studies suggest that the drugs are given out in even higher rates here. Only a handful of hospitals have labs to test whether a patient actually needs antibiotics, and many people self-medicate, buying them over the counter.

As bacteria become resistant to common drugs, stronger antibiotics are in short supply, and without these, doctors are faced with infections they simply cannot treat.

The overuse of antibiotics in human medicine and agriculture has hastened this process, and experts now warn of a looming global crisis. But in many developing countries, the crisis has already hit.

"When you have health care-associated infections from poor sanitation or poor infection control, you have all these readily available drugs given to patients to cure them. Now, when you have resistance to these drugs, there's nowhere to run," said Dr. Emmanuel Irek, a microbiologist at the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital in Nigeria, who has studied resistant infections across Africa.

Even at bigger district hospitals, doctors have a limited arsenal of drugs to call upon, Irek said: "We have the relatively cheaper ones, such as cephalosporins and macrolides [two classes of antibiotics], but when we now talk about resistant bugs, which invariably are due to poor infection prevention and control and poor water, sanitation and hygiene, we don't have the best antibiotics to deal with them."

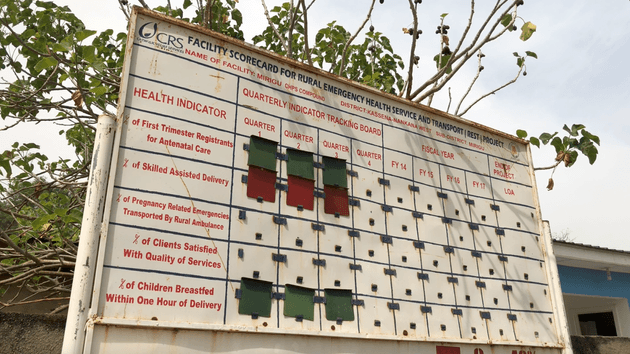

A sign outside Mirigu health centre displaying progress on targets

A sign outside Mirigu health centre displaying progress on targets

A recipe for infection

One in three health care facilities in low and middle-income countries doesn't have readily available water, according to the World Health Organization.

In poor, rural areas like Mirigu, this figure can double. Instead, vats of water are filled for washing hands and instruments. There's no safe way to dispose of medical waste.

It's a recipe for cross-infection, all largely solvable with running water.

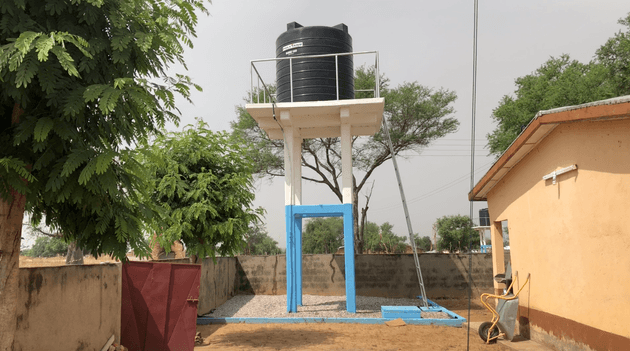

Until the nonprofit WaterAid put in the water supply at Mirigu a year ago, staffers would fill containers from a shallow borehole that would often run dry. Women with newborns would have to walk home to wash, often bloodied and carrying their soiled bedding.

The recent installation of running water at the health centre has helped break the cycle of infection and has been a powerful weapon in the fight against growing antibiotic resistance.

The new water source at Mirigu health centre

The new water source at Mirigu health centre

The toilet and shower blocks were finished last year, their bright blue walls distinguishing the new buildings from the old. Now, mothers can shower after labour, and patients can use a toilet that flushes and wash their hands with soap from the old plastic bottles next to each sink.

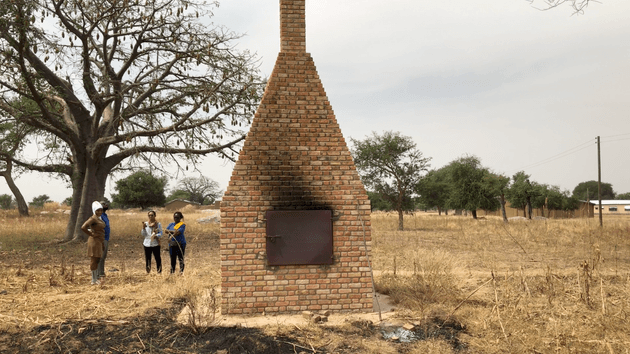

There's also a new incinerator. Many rural health care facilities try to burn medical waste in shallow pits, but at Mirigu, it can now be safely disposed of, further reducing the risk of infections spreading.

The incinerator has greatly reduced the danger of cross-infection from medical waste

The incinerator has greatly reduced the danger of cross-infection from medical waste

"Now, when they come, they feel happy and safe," midwife Akansi said. "It's made a big difference, a very big difference. I think it has reduced - and it will even reduce more - infections in the health care facility."

Although awareness of antibiotic resistance among patients remains relatively low in developing countries, word can spread quickly that conditions in a health facility have improved, meaning more patients seek care.

One study from a district hospital in Sierra Leone reported that more than half of women who had caesarean sections would contract sepsis, a potentially deadly bacterial infection of the blood. After the operating theatre and labour ward were fitted with a better water supply and lighting and staffers were trained on proper hygienic practices, cases of sepsis dropped to less than 1 in 10 women.

Within six months, deliveries at the hospital doubled as patients quickly learned that the services at the maternity unit had improved.

A global problem

Antibiotic resistance is a growing global crisis that will hit the world's poorest people hardest. Estimates show that 10 million people a year will die worldwide from the effects of superbugs by the middle of this century. Four million of those deaths will be in Africa unless radical action is taken to deal with the problem.

Efforts to improve sanitation and hygiene in Ghana's health sector are part of wider plans to slow the growing threat of superbugs. It is one of only two countries in West Africa to publish its action plan to tackle antibiotic resistance, a target set by WHO for all member states to deliver by the end of 2018.

Many more countries are still developing plans, despite the deadline having passed.

"We can only be as strong as our weakest link," said Mirfin Mpundu, head of ReAct Africa, an organization helping governments, including Ghana, produce action plans to tackle antibiotic resistance. He explains how the constant coming and going of people allows disease to spread easily from country to country. "Antibiotic resistance doesn't respect any borders."

Experts say wholesale interventions are needed to stem the rising tide of resistant bacteria, from global efforts to discover new antibiotics to local ones like improving microbiology labs so they can test for resistance. But for many people around the world - like those living in Mirigu - tackling the problem starts simply with safe, clean water.

All photos by Ben Stockton/TBIJ

Our reporting on anti-microbial resistance is part of our Global Health project which has a number of funders. Our work on superbugs (to December 2018) was funded by the European Journalism Centre. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.