Deciphering the new CIA drone base in Niger

Is the CIA getting back into the drone assassination business? That’s the implication of an article published by the New York Times on Sunday, which reveals the existence of a new drone base in a small commercial airport in the West African state of Niger. Though American officials told the Times that the CIA has only used it for surveillance flights so far, an unnamed Nigerian official was quoted as saying that one drone flown from the base had already killed an al Qaeda target in southern Libya, which neighbours Niger.

If the CIA really is about to launch a new targeted killing programme, it will heighten fears that the US is returning to an era of unaccountability and carelessness with civilian lives in its military operations. “It is dangerous and unwise to expand again the CIA’s role as a paramilitary killing organization” warns Hina Shamsi from the American Civil Liberties Union.

The cause for concern may not be immediately apparent to casual readers of the New York Times story. After all, the Pentagon has a drone base of its own in Niger and has already admitted to carrying out several strikes in Libya in the past year. What difference does it make if the CIA has one too?

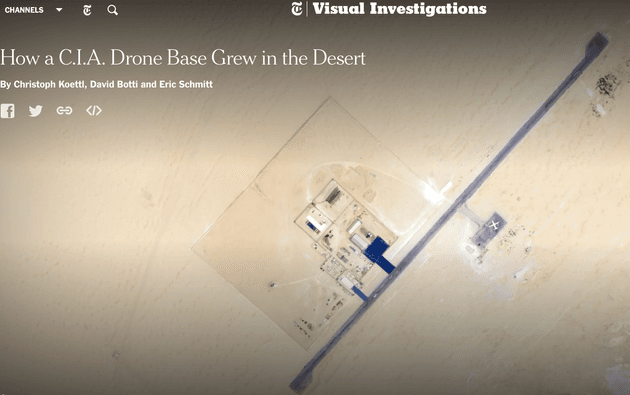

New York Times revealed a new drone base had been built in Dirkou, Niger

New York Times/Planet Labs

New York Times revealed a new drone base had been built in Dirkou, Niger

New York Times/Planet Labs

To understand why the CIA having its own programme sets off alarm bells, you have to go back to the start of the US drone programme, which launched its first strike seventeen years ago. It was the deaths of nearly 3,000 in America in the 9/11 attacks which led to the CIA being authorised to turn drones – which had hitherto only been used for surveillance – into killing machines. The first strike – a botched attempt to kill Taliban leader Mullah Omar – was carried out less than a month after 9/11.

The campaign soon spilled over the border with drone strikes against suspected militants in Pakistan under the presidency of George W Bush, but this was ramped up to a wholly new level by his successor, Barack Obama. Reports started to emerge of civilians being killed in these mysterious strikes in remote parts of Pakistan, but journalists looking to follow up on these accounts faced a problem: as is common practice with CIA operations, the US wouldn’t even officially acknowledge the existence of the programme.

One reason this matters is that accountability is a key part of how civilian casualties are avoided. Put bluntly, policies that reduce the chance of civilian harm, like not hitting buildings, make it harder to go after targets. Being publicly accountable for any non-combatant deaths provides an incentive to set rules of engagement which make them less likely. The Bureau’s research shows that at its peak in 2009, the CIA drone campaign in Pakistan caused at least 100 reported civilian deaths over the course of one year.

Under scrutiny by the Bureau's drones team and after sustained pressure from civil society organisations, the Obama administration did take some limited steps towards addressing the problem. The civilian casualty rate in Pakistan decreased, and the campaign there started to wind down. The Pentagon’s Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) became the primary agency for strikes in Yemen, meaning that the operations could be talked about at least, though the CIA continued to conduct some of its own strikes there too. In its latter days, the administration published some of the policies guiding its use of force in previously secret engagements outside of declared battlefields, as well as aggregated estimates of civilian casualties.

Under Obama’s successor Donald Trump however, policy has been shifting in the opposite direction. In May this year, the administration missed the deadline for releasing casualty data, and said they were reconsidering Obama’s policies in this area.

What the latest development in Niger means is not clear. The new site could still be primarily used for intelligence gathering. Even if it does become the launching point for strikes, it does not necessarily mean a return to the bad old days of the early drone war in Pakistan. The CIA has got better at avoiding civilian casualties since then, and some have argued that the agency is held more accountable for its operations than the Pentagon, by policymakers if not the general public, because its Congressional reporting requirements are more onerous.

Chris Woods of Airwars, formerly the lead reporter on the Bureau’s drone work and author of an acclaimed book on drone warfare, has assessed that at the very least, the difference in accountability between JSOC and the CIA is negligible. The development of a CIA drone programme in Niger may mean little more than a tactical victory for one side in the perpetual tussle between the agency and the military for prestige and influence in Washington.

But the New York Times’s story resonates uncomfortably with other signals on accountability and civilian harm being sent out by the Trump administration. While waiting a clearer indication of the future, observers can only draw on the past, and that is not particularly encouraging. “Limiting the CIA’s role was one of the few constraints President Obama placed on the US’s program of lethal strikes abroad, especially outside recognized war authorized by Congress” says Hina Shamsi. “Very recent history shows that the CIA has killed civilians, caused justifiable outrage, and sought to shield itself from accountability with absurd secrecy arguments.”

Header picture: Predator 3034 - the first drone to kill a human