Was allergy poster boy given too many drugs?

Great Ormond Street Hospital experts criticised for over-treatment of some patients

Blond and sweet-faced, Tylor Savage made headlines a decade ago as “the boy who is allergic to almost every food”.

The mystery illness that sent the ten-year-old’s weight plummeting to four stone baffled a succession of doctors, and it was not until he reached the world-famous Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) that he was finally diagnosed with a rare gut disease. The story reached the US, where he appeared on TV, alongside his father and sister, with a GOSH consultant interviewed. Fitted with a feeding tube and treated with a range of strong medicines, he was back at school and thriving, or so media reports said.

But there is much more to the story of the angelic allergy poster boy - and to the GOSH department that cared for him - as the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, working with TV company Amazing Productions, has discovered.

It’s a story of a bolshie Essex teenager who defied doctors at the country’s top children’s hospital because he felt the drugs they prescribed were making him ill; of an allergic disorder so nebulous experts agree on little about it; of a highly specialised medical unit that misdiagnosed and over-treated some of its young patients; of a series of investigations and enquiries over seven years which raised serious issues about the department, and of some doctors who felt their concerns were not being adequately addressed.

Back in 2006 referring Tylor to GOSH was the obvious thing to do. “I had stomach problems and diarrhoea from the age of nine or ten”, he told the Bureau. Local doctors in Essex initially blamed stomach infections, but when his symptoms persisted they admitted defeat and sent him to London.

This is part of a series of Bureau articles looking at the gastroenterology department in Great Ormond Street Hospital

Find out moreAs a super-specialist centre, GOSH has an outstanding reputation and is one of Britain's best-loved hospitals for children. It cares for the sickest and most complex child patients in the country. Many children whose doctors have given up on them, who suffer from the rarest diseases or whose symptoms cannot be explained, have found hope, as well as cutting-edge treatments, behind its doors. It is widely trusted and its doctors have international reputations.

Consultants from the hospital’s gastroenterology (also known as gastro) department, which manages children with gut disorders, put a camera into Tylor’s intestines and took biopsies. They diagnosed him with a condition known as EGID.

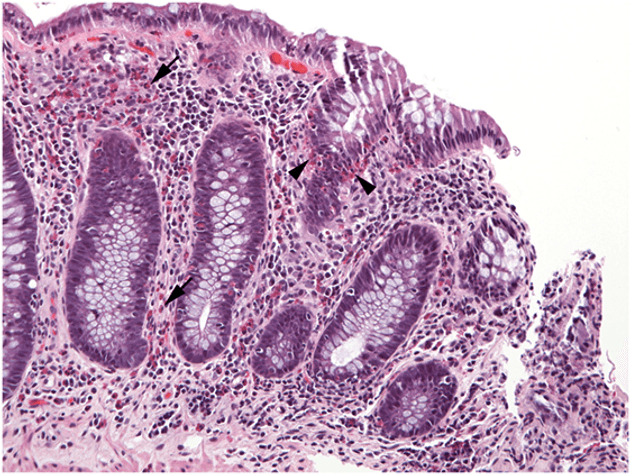

GOSH had built a name for itself as a centre for diagnosis and treatment of this rare and controversial condition. EGID occurs when white blood cells called eosinophils accumulate in the lower gut for no apparent reason. This is called Eosinophilic Gastro Intestinal Disease (EGID).* In some cases this may cause inflammation and symptoms such as abdominal pain and diarrhoea.

However, there is no medical consensus on how to diagnose or treat it or even agreement on what a normal level of these white cells should be. A gastro consultant at GOSH, who is one of the country’s lead experts on the condition, once described EGID as “nebulous” and its diagnosis and management as “dark arts”.

Tylor was put on a restricted diet which cut out soya, egg, wheat and diary and he was prescribed drugs, including an anti-inflammatory called Sulphasalazine. This can have side effects such as nausea and vomiting and in rare cases can damage the liver.

He was later given steroids and Azathioprine, a type of immunosuppressant. While this drug also dampens inflammation it works by weakening the body’s immune system, leading to an increased risk of potentially deadly infections and certain types of cancer.

By spring 2007 things had not improved. GOSH took another biopsy but the results were not illuminating. A letter written by a GOSH doctor at that time, seen by the Bureau, said. “We do not understand why he displays all these symptoms.”

In a single month he was admitted to Colchester Hospital four times with abdominal pain, diarrhoea, vomiting blood and “passing out”.

The GOSH doctor decided to put a tube into the boy’s stomach so he could be fed during nights with “elemental” formula - an anti-allergy liquid feed. His mother Linda later described the tube as a “godsend”.

In October 2007 the twelve year old and his father travelled to New York to appear on a US television show, (pictured above). Tylor talked about his condition and how much GOSH had helped. A press report on his appearance described him as “thriving”.

But his medical notes, which he has given to the Bureau, paint a more complicated picture. While the tube-feeding ensured he did not starve, his symptoms never went away. The next four years were punctuated by frequent hospital admissions and more medication. Sulfasalazine was stopped but for the next three years he continued on Azathioprine, supplemented with fortnightly doses of antibiotics to combat the risk of infection, frequent courses of steroids, and up to five other drugs. His notes show that any respite was usually short-lived.

“I don’t think the Azathioprine did anything, otherwise why was I still in hospital every month?” Tylor said.

A common side effect of Azathioprine is an upset stomach, but it also makes patients more vulnerable to infections. While taking it Tylor was hospitalised several times after contracting viruses including chicken pox. According to his hospital records the infections, in turn, made Tylor’s gastro symptoms worse.

Tylor also developed severe mouth ulcers, which he had suffered from for years and can also be a side effect of Azathioprine. His GOSH consultant’s response was to suggest yet more medication to treat the ulcers - this time, Thalidomide.

“I will be interested to see if this also has a significant influence on the remainder of his gut”, the consultant wrote in a letter to Tylor's doctor in Colchester, announcing the plan to start the boy on the drug.

Thalidomide is infamous for causing severe birth defects in babies whose mothers were prescribed it for morning sickness in the 1950s. It can also affect male sperm. According to Tylor’s mother Linda, the prescription caused consternation at Colchester, which summoned the family to discuss it.

The Colchester doctor “said she assumed GOSH had explained all the risks involved and we said no, they hadn’t”, Linda recalled. “Tylor was 15. She explained that if Tylor was to have a baby there was a risk of the child being born with deformities. I asked her if she would put a relative of hers on it and she said ‘no I wouldn’t’. So we decided against it.”

An image of esoniphils in the colon

Photograph: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, United States

An image of esoniphils in the colon

Photograph: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, United States

Defining eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorder (EGID)

Until 2016 GOSH was the leading UK centre for the diagnosis and treatment of allergy-related gut conditions known as eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders. These are defined as unexplained increases in a type of white blood cell, (known as eosinophils) linked to inflammation in the gut. Eosinophilic disorders of the lower intestine are collectively called EGID.

In the UK, doctors diagnose EGID according to numbers of eosinophils and signs of gut inflammation shown in tests and clinical symptoms including vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhoea and constipation. There is no single view on how many eosinophils must be present or on the cells’ correlation with symptoms and there are no national or international guidelines on EGID’s diagnosis and treatment to inform doctors’ decisions.

Some doctors have questioned whether the disease even exists in its own right.

Make change possible

Investigative journalism is vital for democracy. Help us to expose injustice and spark change

Click here to support us

Turning point for Tylor

Tylor’s attitude to both his illness and his doctors began to change in 2011, as he approached his sixteenth birthday.

In February, after an internal test showed white blood cells remained in his gut his GOSH consultant prescribed him another immunosuppressant: Sirolimus - a medication more frequently used to stop rejection of transplanted kidneys. Shortly after he began taking it Tylor developed such explosive diarrhoea he had to be put on an intravenous drip.

His local consultant in Colchester immediately stopped the Sirolimus and later wrote to GOSH asking if it should be re-started. The GOSH consultant replied that it should but Tylor refused to take it, given the previous effects.

He had now been taking immunosuppressants for almost five years. He vowed that after he turned sixteen he would stop all his medications. He also told his family he would ask for his feeding tube to be removed.

His Colchester doctor’s response was to write to a psychologist asking for him to be seen urgently to “address some of these issues”. Letters from this doctor record Tylor saying he felt most of the medications were “making no difference” and he was not sure why he was taking them. He also raised concerns over medical side effects.

“I’d read the pamphlets that come with the meds”, Tylor explained to the Bureau. ”The side effects sounded a lot like what I had.”

He was not to know, but around the same time he started to challenge his doctors’ advice, concerns were being raised about the GOSH department caring for him.

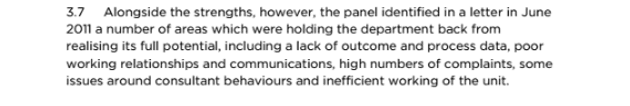

That year, 2011, GOSH managers had asked an external panel to examine the department. “High numbers of complaints”, inefficient working practices, “issues around consultant behaviours” and - crucially - “a lack of data showing the effectiveness of treatments being used” were identified in the panel’s letter (referred to below in screenshot) to GOSH in June of the same year.

Section referring to the panel letter, taken from the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health 2015 report about the gastro service, and held by GOSH

Section referring to the panel letter, taken from the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health 2015 report about the gastro service, and held by GOSH

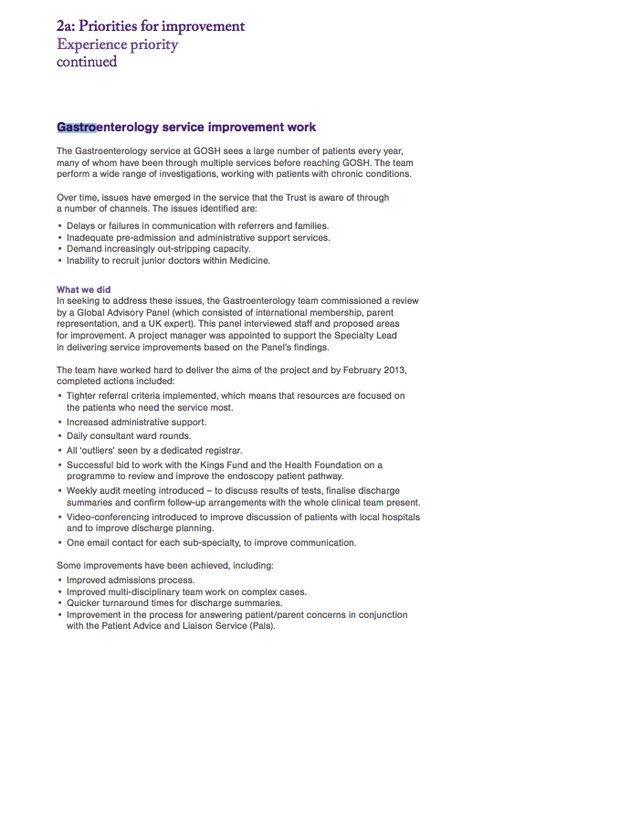

Issues in the Gastro department were also mentioned in GOSH's 2012/3 annual report (pictured below).

Screenshot of GOSH's 2012/3 annual report, referring to improvement work in the gastroenterology service

Screenshot of GOSH's 2012/3 annual report, referring to improvement work in the gastroenterology service

In August 2011 Tylor had an appointment at University College London Hospital (UCLH), which was attended by his GOSH consultant, to start his transition from children’s to adult services. There, the doctors discussed possible changes to his treatment plan. But after a second visit a month later, he refused to attend any more appointments.

“I completely lost faith in doctors”, he told the Bureau. He had also started on a training course to become a professional chef, which led him to test his tolerance for new foods.

“The people at the college said I couldn’t do the course because I wouldn’t be able to try the food”, he explained. “I started the course and tasted the food and nothing happened.”

Despite his mother’s fears, and against his doctors’ advice, he stopped all his medications and began to wean himself off his feeding tube.

Back at GOSH, concerns were beginning to emerge over the unit’s approach to EGID, the rare disease with which Tylor had been diagnosed. In 2012 GOSH organised a lecture to allow clinicians across the hospital an opportunity to “discuss doubts and look at evidence” about the disease.

Cases and GOSH reaction

A year later, a mother of two GOSH gastro patients was arrested for lying about her children’s symptoms in order to claim benefits. One of the children had been diagnosed with EGID, fitted with a feeding tube and treated with a cocktail of drugs for eight years. Tests found no trace of disease for much of this time, but both treatment and tube-feeding had continued because the mother insisted the child was ill and would not allow her to stay at the hospital for observation.

An expert who later scrutinised the case concluded that from 2009 the risk that the mother was making things up should have been obvious to those treating him.

The case raised serious questions about the management of the child’s diagnosis and treatment, and GOSH’s communication with other hospitals and agencies.

In response, GOSH introduced meetings involving doctors and consultants from a wide range of fields - known as multi-disciplinary team meetings - aimed at identifying parents who have fabricated, or exaggerated, their children’s illness.

Got a Story?

We welcome tip-offs from the public and we always protect our sources

Find out how to work with usMeanwhile, Tylor was delighting in a life without medical intervention. “In my first year after leaving GOSH and school I reintroduced plain foods into my diet and by the second year I was eating everything,” he says. He passed his catering course with distinction.

In spring 2013 Tylor visited UCLH hospital, to ask for his feeding tube to be removed. His consultant was astonished. “He does appear extremely well in himself. He really has done an amazing job in turning things around … he has put on around 6kg in weight and several centimetres in height since we last saw him. He is now eating completely normally”, the consultant wrote in a letter, following the appointment.

The letter also noted Tylor’s fears that GOSH may have over-treated him, saying: “He feels the best he has done for years and looking back has some concerns that he may have been on immunosuppressive medication unnecessarily for some time.”

The complexity of Tylor’s condition, the fact that some children grow out of EGID naturally and the divergence of expert opinion on how to treat it mean it is hard to say whether his case should have been handled differently.

What can be said is that he was not alone in having worries about potential over-treatment by GOSH’s gastro service. Some senior doctors and other staff inside and outside of the famous hospital were also concerned about aspects of the department’s approach to EGID.

Over the following years GOSH was to bring in one external team after another to review the department and its patients. As questions about possible EGID misdiagnosis and over-use of immunosuppressant drugs mounted, hundreds of existing patients were re-assessed and the department cut the number of patients it took on by half.

Making sense of this complex story has not been easy. The Bureau and Amazing have spent over a year investigating the service and have spoken to dozens of families and doctors with concerns. Many questions still remain.

The hospital has admitted some patients were misdiagnosed with EGID and over-treated, but says the Bureau has “an incomplete understanding… of the facts” around the extent and seriousness of this.

GOSH has declined to share the findings of some key reviews on grounds of confidentiality or to answer detailed questions on the numbers of children who may have been affected.

The Royal College steps in

In December 2014, GOSH asked the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) to carry out a review. GOSH highlighted worries over EGID in its terms of reference to the College. “A large number of patients within the gastroenterology service have this diagnosis,”it said. “Concerns have previously been raised via a number of routes ... and issues continue to be raised.”

The Royal College’s experts are often called on to act as consultants, bringing a fresh eye to parts of a hospital that managers feel may be under-performing or dysfunctional.

Throughout May and June 2015 Royal College experts interviewed more than 100 clinicians and other staff who worked in or with the department. In July that year, before their report was even finalised, the experts wrote an urgent letter to the hospital (letter partially redacted). The letter said: “Information shared with us … leads us to believe that the way the service is currently delivered may be causing avoidable harm to children”.

The experts had been told the gastroenterology team was diagnosing some conditions including EGID, “excessively without, we were told, consistent criteria or thresholds”, the letter added.

Senior doctors from other hospitals had even advised, “they will no longer send patients to [the service] for second opinions because they are worried they will return with an unexpected rare disease diagnosis”. And numbers of invasive tests, involving cameras inserted into the intestine, “appeared to be significantly out of line” with other specialist hospitals.

The experts advised a “swift but thorough review” of a sample of children currently being treated for a type of EGID.

GOSH responded by agreeing to take urgent action.

The Royal College’s full report, which was finalised in August 2015, which the Bureau obtained through an FOI request, paints a picture of doctors who had become professionally isolated and “in effect lost touch with many of their patients, families and colleagues”.

Relationships between the consultants and management had “almost completely broken down” while relations with general paediatricians, ward staff and referring hospitals were also poor, the report concluded.

Some general paediatricians had “unresolved safeguarding concerns” about gastroenterology patients. Some nurses felt “unable to challenge the consultants” and a “significant number” of staff reported feeling “too scared” to raise safeguarding issues internally, while others said they had raised concerns but felt no action had been taken.

Screenshots of some sections from the 2015 Royal College report on GOSH

Screenshots of some sections from the 2015 Royal College report on GOSH

GOSH brings in expert panel

The hospital commissioned a panel of external experts to review the notes of a sample group of patients being seen by the gastro department.

Dr Rob Heuschkel, head of the regional paediatric gastroenterology service in Cambridge, was invited to join the panel. He had had concerns about GOSH’s approach to EGID for a long time, he told the Bureau.

“I’d been seeing children coming from that unit on multiple medications for a condition I would not be treating in the same way”, he explained.

He had just taken on one such patient, 14-year-old George Wood, whose family had recently moved to the area. Since he was a baby George had suffered from allergies and stomach problems and he had been a GOSH patient since age four. At seven, GOSH diagnosed him with EGID.

His doctors prescribed powerful medicines and a restricted diet. At first the drugs seemed to work. But as George grew older his mother began to lose faith. “We just got medication after medication”, she told the Bureau. “But his symptoms never went.”

She added: “We had immunosuppressants... we had antihistamines, we had anti-reflux medications, we had medications that were to make the bowel stop spasming, to stop the pain, we had medications to help him go to the toilet, we’ve also had medications to stop him from going to the toilet. Medications morning, lunchtime and evening.”

Fear of infection ruled the family’s life, affecting George’s school attendance and ability to socialise. He also suffered from hypermobility syndrome, which affected his legs.

By 2015 his GOSH doctors had stopped his immunosuppressants and were attempting to broaden his diet. He had also received psychological help. But he was still taking eight different drugs, including antibiotics three times per week, and his ability to walk was very limited.

Dr Heuschkel wanted him weaned off half of this medication, with all drugs stopped within the next few months.

At first, both George and his mother were reluctant to proceed in that way. “I walked away and burst into tears,” Michelle recalled. But after some discussion, the family agreed they would follow Dr Heuschkel’s advice.

“Nothing got any worse,” Michelle said. “Suddenly George started walking a bit more.”

By October 2015 George was no longer taking any medication, had no dietary restrictions and was receiving more psychological help. He had even managed to complete a charity walk.

“I went from not being able to walk to walking 13 miles”, he said.

With George’s case fresh in Dr Heuschkel’s mind, he accepted GOSH’s invitation to join four other experts on the review panel. “I thought...the management at Great Ormond Street was prepared to grasp the nettle and investigate”, he said.

GOSH imposed restrictions on new referrals to the gastro service while the investigation proceeded. The panel’s task was not easy: some relevant notes were unavailable and the panel’s remit did not include speaking to the doctors involved in each case. One month after starting the panel called a halt to their work, telling GOSH they had seen enough.

The panel’s final report, submitted in February 2016, expressed concern over 14 out of the 18 patients they had reviewed. Their report echoed that of the Royal College, raising concerns over an overemphasis on EGID, over-investigation and over-treatment.

A “significant number” of cases had EGID diagnoses that were “very unlikely” to have been made in reviewers’ own institutions, the report said. In one case, histology test results had been completely normal.

The cases showed an “overemphasis on inappropriate… dietary restriction” and “over treatment, particularly with immunosuppressive drugs for prolonged periods without adequate documentation of the risks and benefits”, the report said.

The team concluded the gastro department had “put patients with relatively straightforward, uncomplicated or self limiting gastrointestinal symptomatology … at risk”.

GOSH's next steps

The hospital responded quickly to the panel’s findings. An overhaul of governance and safety procedures was set in motion and hundreds of GOSH gastro patients had their treatment plans re-assessed.

GOSH managers also asked consultants from a number of other hospitals including in Leeds, UK and Cincinnati, in the USA, to look at test results for the 14 patients highlighted by the expert panel. GOSH has said the many reports that came out of this further process provided a different picture to that found by the panel.

The hospital said it did not have permission to release most of the assessments to the Bureau but was able to provide one report. This report focused on five of the 14 cases. The report’s author agreed that one patient had been misdiagnosed and left on some drugs longer than necessary, but reached different conclusions from the expert panel team on the other four cases. He had no major concerns about these cases.

GOSH believes this means the expert panel’s findings should be given “only very limited weight”. As the author of the more in-depth report had access to more notes and also spoke to the treating doctor, his findings were more robust and reliable than those of the expert panel, the hospital said.

In addition to the in-depth reviews of the 14 cases the hospital arranged for external doctors to re-examine hundreds of the department’s patients. These included children who were taking potent drugs without a clear diagnosis and a random sample of all other patients in the department - some 300 cases in total, although GOSH has not told the Bureau how many of those were EGID cases.

GOSH said the process found no major concerns over misdiagnosis of EGID and that in total only 25 patients had their treatment changed and there was “no consensus” on whether over-treatment had occurred.

Section from email from GOSH to the health regulator, the CQC, on 9 May 2016

Section from email from GOSH to the health regulator, the CQC, on 9 May 2016

In an email sent to the regulator, (section reproduced above) the CQC, in May 2016, GOSH stated that there had been no physical harm to patients but it acknowledged there had been “a psychological impact” on children. This included children “believing they are very sick” and missing school.

Sections of December 2016 memo, circulated by GOSH's then medical director

Sections of December 2016 memo, circulated by GOSH's then medical director

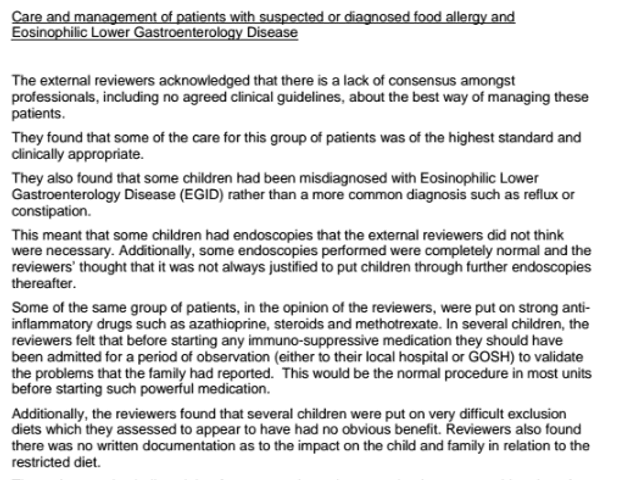

The Bureau has also obtained, via FOI, a summary of the overall findings of the entire review process sent by the then medical director of GOSH, Dr Vinod Diwakar to commissioning body NHS England and the CQC in December 2016.

Whilst some care was “of the highest standard”, some EGID and food allergy patients had been misdiagnosed, the memo said (sections pictured above).

“Some patients were exposed to the risks of unnecessary invasive investigations, difficult food exclusion diets and drugs with potentially serious side effects,” had been identified by the reviewers the memo added. In some cases, GOSH’s use of steroids, drugs that suppress the immune system and heavily restricted diets, was “outwith the norm for paediatric gastroenterology units in the UK”, it added.

Some patients had also been misdiagnosed with EGID, “rather than a more common diagnosis such as reflux or constipation” and put on immunosuppressive drugs before the symptoms reported by their families had been validated.

Overall, GOSH’s approach to EGID and complex food allergies was at the “aggressive end of the spectrum”, the memo stated. The memo said the hospital was taking action to bring treatment into line with other hospitals. GOSH would stop taking patients with suspected EGID it said, and all clinical decision making would be subjected to peer review and challenge.

Transparency

In December 2016 GOSH published a statement on its website, pictured above. It said reviewers had found some children had “unnecessary endoscopies and exclusion diets and they questioned some treatments”. The statement added: “There was no evidence of any long-term consequences to these patients” and it said GOSH had put in place measures to ensure this does not happen again.

In addition GOSH said all patients who needed to know about potential problems were told. All its external communications were sent to the healthcare regulator and NHS England, it added.

But in the view of Dr Sandhia Naik, a senior paediatric gastroenterologist at Barts NHS Trust, some patients have been harmed by the GOSH service’s approach. In a letter to a senior manager at her trust discussing patients referred by GOSH to Barts for second opinions she said some had been put on treatment she believed “should never have been started”.

“It is my professional opinion that patient harm has occurred”, she wrote. GOSH insists that the reviews uncovered "no evidence of long-term consequences for any patients as a result of their care".

Questions also remain about how many people may have been affected and the hospital has been criticised by some for a perceived lack of transparency.

In December 2017, the Royal College completed its latest follow-up review of the department, which was published by GOSH a few weeks ago. The report said: “Many patients were not satisfied with the communication from the trust… many families still don’t know what the situation is for their child.”

The Royal College reviewers were told the department’s closure to referrals caused “utter chaos”, with other specialist hospitals becoming “overwhelmed” with patients and families left “unsupported and confused”.

Dr Heuschkel agreed: “In my opinion it is utterly unacceptable that a highly respected institution can close a major service indefinitely to most new referrals, without giving the families and referring doctors the full details of the seriousness of the medical concerns that led to this decision.”

GOSH says it had to halt referral in order to "complete the review process and implement the recommendations"

Some patients treated by GOSH gastro doctors say they were not told about the lengthy review process.

Evie Gormley, one of these patients, (pictured above) was not reviewed despite having taken the immunosuppressant Azathioprine for many years at the recommendation of a GOSH consultant. She saw the GOSH specialist at a joint clinic at her local hospital. Under this arrangement local doctors at the clinic wrote her prescriptions. The hospital said this meant it was “not responsible” for Evie’s care and it would be “inappropriate for it to review her treatment”. Evie’s mother was not informed of any concerns about GOSH’s gastro service.

GOSH maintains that all who needed to know about potential problems have been told and that it has correctly balanced the need for transparency against the risk of causing unnecessary panic and alarm. It says the reviews were “comprehensive and thorough”, assessed “all relevant cases” and found that “the vast majority of care in the service was good”. Nonetheless GOSH will now reach out to patients such as Evie to make sure its is “doing all we can to learn from their experience”.

Moving on

Overall the latest Royal College report, which GOSH made public in 2018 in its March board papers (Appendix M, report pictured above), found “significant improvements” and “good progress in dealing with the immediate issues of concern. It highlighted “very good senior and operational leadership”. New safety measures put in place, including team meetings to discuss treatment before and after each gastro patient was seen in clinic. Noting the service was doing half the work it had previously, the College said normal activity should be restored.

But the Royal College also found some “deep-seated” attitudes persisted. Some consultants “remained sceptical about the need for change”, and were “reported to focus on medical investigations before considering … psychological causes for symptoms”.

Diagnostic staff said children were still being referred for tests “with insufficient justification and checks”. And some children had been kept on strict dietary regimes for over six months without review.

The report recommended that general paediatricians should have a greater role in supporting gastroenterology and could “bring objectivity” to complex and perplexing cases. And while safeguarding teams had been strengthened, it was felt the culture in the department was still not sufficiently open. Some staff reported that they still did not feel confident to raise concerns over patients whose treatment they thought should be delayed or reduced.

The College team said there should be another review of the service 12 months after the lifting of referral restrictions.

In its formal response to the Royal College report, GOSH said it was confident that patients and families were now seeing the benefits of improvements made. It said: “we are however disappointed that some anecdotal information has been included in the report and is unsubstantiated and not adequately triangulated”… “the progress the department has made [must not be] undermined by unverified information”. It had developed an action plan to address areas still requiring improvement, it added.

NHS England commissions specialised services from GOSH. Dr Michael Marsh, a medical director at NHSE, told the Bureau in August 2017: “We have been working very closely with Great Ormond Street who are putting in place measures to prevent this happening again. We are saddened to hear that any child, young person or family have been put through unnecessary treatment.” This week NHS England added that the hospital "rightly brought in experts from across the UK and the US to review what had taken place, and they are now putting in place measures to ensure the right care is always offered for these rare and complex conditions."

GOSH told the Bureau: “the vast majority of care in the service was good and there was no evidence of long-term consequences for any patients as a result of their care” but the trust also apologised for any failings in the gastro department. GOSH said the department was working in a “complex area of medicine where there are no agreed clinical guidelines”. The hospital said: “we always strive to provide the best possible care”, but “we haven't always got this right” and “for this we are very sorry”.

While GOSH and its doctors have largely moved on with lessons learned from a troubled period in the gastro department’s history. George still struggles with nausea and other gastro problems, but his doctors believe that these are mainly psychological.

His mother Michelle says he barely goes out and she believes that “psychologically the damage that has been done from all of those years of being medicalised has started to take effect”. She adds: “If I could turn the clock back, I would go along with someone who wanted to deal with it in a totally different way.”

Tylor Savage and family, photographed by Guy Cater

Tylor Savage and family, photographed by Guy Cater

Tylor, in contrast, has moved on. In March 2016, his girlfriend gave birth to a baby girl. The family (pictured above) now lives in Nottingham, where he has fulfilled his childhood dream to work as a chef.

“I eat KFC once a week because it has all the stuff in it I wasn't allowed. I just love it,” he says. His intestines are still not completely normal and maybe never will be, but he has now learned to handle his problems."

Tylor believes the team at GOSH was “not doing anything but their best” but wishes he had stopped all treatment sooner.

As for hospitals, he never wants to near one again. “I avoid them now. I won’t even go and visit people – I do Facetime but I won’t go in.”

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism had been working in conjunction with Amazing Productions who produced “Great Ormond Street: The Child First and Always?” as part of the Exposure strand which was transmitted on ITV at 22.40pm on Wednesday 18th April. You can view it here: https://www.itv.com/hub/great-...

Header photo, from the Savage family (copyright unclear). Please contact us if you own copyright.

*Our definition of EGID excludes eosinophilic oesophagitis - there are clear diagnostic and treatment guidelines for this disease.