Seven year saga of Great Ormond Street department that over-treated some children

Specialists at Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) misdiagnosed some children with a rare allergic disease and over-treated them with drugs that can have dangerous side effects, an investigation by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and Amazing Productions has found.

A number of senior doctors from inside and outside GOSH have been asking serious questions over the past seven years about the gastroenterology (also known as gastro) department, which manages children with gut disorders.

GOSH has now apologised for any failings. The hospital told the Bureau that this is “an incredibly complex area of medicine where there are no agreed clinical guidelines” and that, although the department strived to provide the best possible care, “we haven't always got this right. For this we are very sorry”.

From 2011 onwards, GOSH brought in one external set of experts after another to review the service. One team’s findings raised such significant concerns that in late 2015 the department stopped accepting most new patients while further investigations were carried out. The unit is still only doing half the work it was but the hospital is talking to commissioners about increasing the number of referrals again.

The department’s approach, characterised in a GOSH internal document as “aggressive”, led to a number of children being misdiagnosed with a rare intestinal disease and given unnecessary drugs with potentially serious side effects, the investigations found. Some staff had concerns, but had felt too scared to speak out.

The most recent review, published last month, found significant improvements had been made. But despite stringent new safety measures children were still potentially at risk of too much intervention.

Most of these reviews have never been published and until now, few details about them have been made public.

Seven years of reviews

GOSH is one of Britain's best loved children's hospitals. It has a worldwide reputation for treating sick children and for cutting edge science. It is widely trusted, seen as an outstanding provider and its doctors have international reputations.

GOSH commissioned its first review into the gastro service as far back as 2011. An external panel uncovered “issues around consultant behaviours” and a lack of data showing that treatments used were effective. There were also high numbers of patient complaints.

An external senior consultant reviewed the service again the following year and identified several themes for improvement, which a newly appointed manager shaped into an action plan.

Internally, concerns were also raised in 2012 over the unit’s approach to a rare allergy-rated gut disorder. Those concerns resurfaced in 2013, when the mother of two GOSH gastro patients was arrested for lying about their symptoms. One of the two children, diagnosed by GOSH with the rare disorder, had been given a cocktail of drugs and tube-fed for years despite tests showing no abnormalities for most of that time.

Multi-disciplinary team meetings aimed at weeding out parents who fabricate their children’s illness were introduced to the gastro service and the mother was later jailed for child cruelty and benefit fraud.

But complaints about the gastro service continued and concerns about over-treatment lingered. In spring 2015, GOSH asked the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) to review the department again. The College uncovered a breakdown in relationships between the gastro consultants, management and other GOSH staff and inadequacies in child protection, with “significant numbers” of staff saying they felt “too scared” to raise concerns.

Separately, the Royal College reviewers wrote an urgent, confidential letter to GOSH’s medical director warning that the service “may be causing avoidable harm to children” - a claim which GOSH has subsequently denied.

The College had been told that the gastroenterology team was diagnosing some conditions, including the rare allergic disease, “excessively, without…consistent criteria or thresholds”, the letter added.

Some senior doctors from other hospitals had advised the team they had stopped referring patients to a GOSH doctor “because they are worried they will return with an unexpected rare disease diagnosis”, the letter said.

The letter also raised concerns over numbers of invasive tests being carried out.

GOSH responded in November 2015 by turning away most new referrals to the service. Managers also arranged for experts to reassess hundreds of patient cases, including children diagnosed with the rare disease and those taking powerful medication, such as drugs that suppress the immune system. These drugs reduce inflammation but can raise the risk of deadly infections and cancer.

This is part of a series of Bureau articles looking at the gastroenterology department in Great Ormond Street Hospital

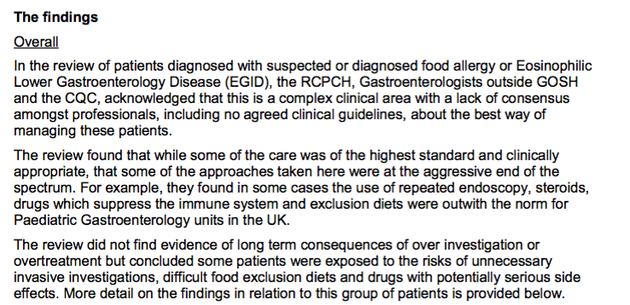

Find out more Extract from GOSH memo circulated by GOSH's then medical director, in December 2016, about the Paediatric Gastroenterology Review

Extract from GOSH memo circulated by GOSH's then medical director, in December 2016, about the Paediatric Gastroenterology Review

Outwith the norm

By December 2016 all the patient case reviews were complete. The department’s approach to the rare disease and food allergy was at the “aggressive end of the spectrum”, according to a memo (extract pictured above) summarising the reviews. Use of steroids, immunosuppressive drugs and exclusion diets was “outwith the norm for paediatric units in the UK”, according to the memo, which was circulated by GOSH’s then medical director, Dr Vinod Diwakar.

“Some patients were exposed to the risks of unnecessary invasive investigations, difficult food exclusion diets and drugs with potentially serious side effects”, the memo said.

Some patients had been misdiagnosed with the rare allergic gut disorder, had undergone unnecessary tests and had been put on powerful drugs before their symptoms had been adequately checked, it added.

The Bureau also obtained two reports on child safety and protection, dated 2016 and 2017, which together highlighted major concerns about weaknesses in the department and in the hospital as a whole. The gastro service is amongst parts of the hospital that receives most child protection cases, one of the reports said, but these were not routinely discussed with the safeguarding team or lessons learned from the cases.

In response to all these reviews and inquiries, GOSH carried out a major overhaul of processes and procedures. New safety measures were put in place, including team meetings to discuss treatment before and after each gastro patient is seen in clinic.

Make change possible

Investigative journalism is vital for democracy. Help us to expose injustice and spark change

Click here to support us Exterior of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, by Katharine Quarmby/the Bureau

Exterior of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, by Katharine Quarmby/the Bureau

When the RCPCH experts re-evaluated the department last summer they found “significant progress had been made” since their first report, with “very good senior and operational leadership”.

But their latest review also shows that attitudes which could potentially put children at greater risk of over-treatment have still not been totally eliminated amongst some consultants, who “remain sceptical about the need for change”.

Patients had been referred for tests “with insufficient justification and checks”, some children “had been kept on strict dietary regimes for over six months without review and others had been recommended exclusion [diets] even before a first appointment, which may not have been necessary”, the Royal College team found.

GOSH December 2016 statement on the gastroenterology review

GOSH December 2016 statement on the gastroenterology review

GOSH released a statement (pictured above) in December 2016, which it put on its website. It said that no patient had suffered any “long term consequence” as a result of the gastro team’s approach. However, the Royal College experts were told that some patients had required extensive psychological therapy after years of treatment now thought to have been unnecessary.

Questions remain over how many children may have been misdiagnosed and over-treated over the years. One of the professionals with ongoing concerns, Dr Rob Heuschkel, head of the paediatric gastroenterology service at Addenbrookes Hospital in Cambridge, believes GOSH should have given "families and referring doctors full details about the seriousness of the medical concerns that led to this decision” to stop most new referrals of EGID patients to the department. “In my opinion there has been too little transparency”, he said.

Peter Walsh, head of patient safety charity Action against Medical Accidents, agreed, saying: “It is vitally important that, when there are concerns about a particular type of treatment, the concerns are shared with other health providers.”

GOSH told the Bureau they had "in-depth dialogue with the patients whose care packages were reviewed and ensured all gastroenterology patients were aware of the review" and also shared review findings with "our regulators, the CQC, and NHS Improvement and NHS England".

Last year Dr Michael Marsh, a medical director at NHS England, which commissions specialised services from GOSH, told the Bureau: “We have been working very closely with Great Ormond Street who are putting in place measures to prevent this happening again. We are saddened to hear that any child, young person or family have been put through unnecessary treatment.” This week NHS England added that the hospital "rightly brought in experts from across the UK and from the US to review what had taken place, and they are now putting in place measures to ensure the right care is always offered for these rare and complex conditions".

The hospital told the Bureau that "the vast majority of care in the service was good and there was no evidence of long-term consequences for any patients as a result of their care."

It later emerged that GOSH spent £130,000 with Schillings reputation management firm trying to handle the Bureau/ITV story.*

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism had been working in conjunction with Amazing Productions who produced “Great Ormond Street: The Child First and Always?”, part of the Exposure strand transmitted on ITV on Wednesday 18th April. You can view it here: https://www.itv.com/hub/great-...

*This line was added on September 30 2018.

Header image, of the Great Ormond Street Hospital main entrance, by Juliet Nagillah/the Bureau