Battle for the future of Parma ham

How Parma ham became battleground for future of Italian food

In April 1945, the countryside around the northern Italian city of Parma rumbled with the sound of warfare. Allied troops and Italian partisans fought the remnants of the German and Italian armies in the battle of Collecchio - one of the last major clashes of the war to take place on Italian soil.

Nearly 73 years later, the city, in Italy’s Emilia-Romagna region, is perhaps better known for its food, architecture and university - one of the oldest in the world - than its part in the war. But it’s now the setting for a very different type of conflict; an increasingly bitter war of words being played out between producers of one of the world’s most iconic meats and concerned campaigners for animal protection.

The region is the heartland of Italy’s billion dollar “prosciutto” industry, producing around nine million Parma ham legs each year for consumption both in Italy and for export globally. The meat has become a global favourite with consumers, whether picked up in the supermarket aisle, served in restaurants or bought from artisanal delicatessens.

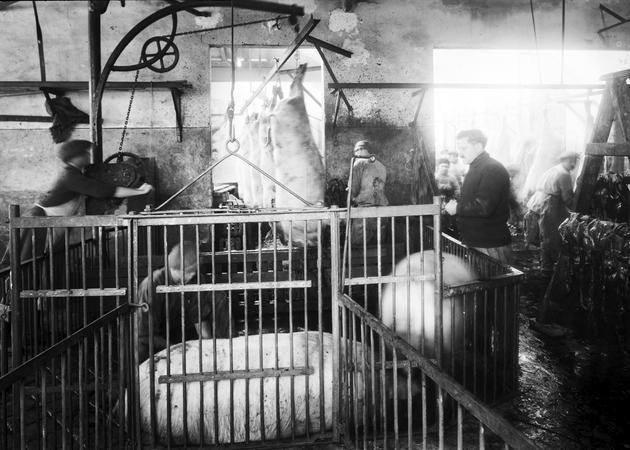

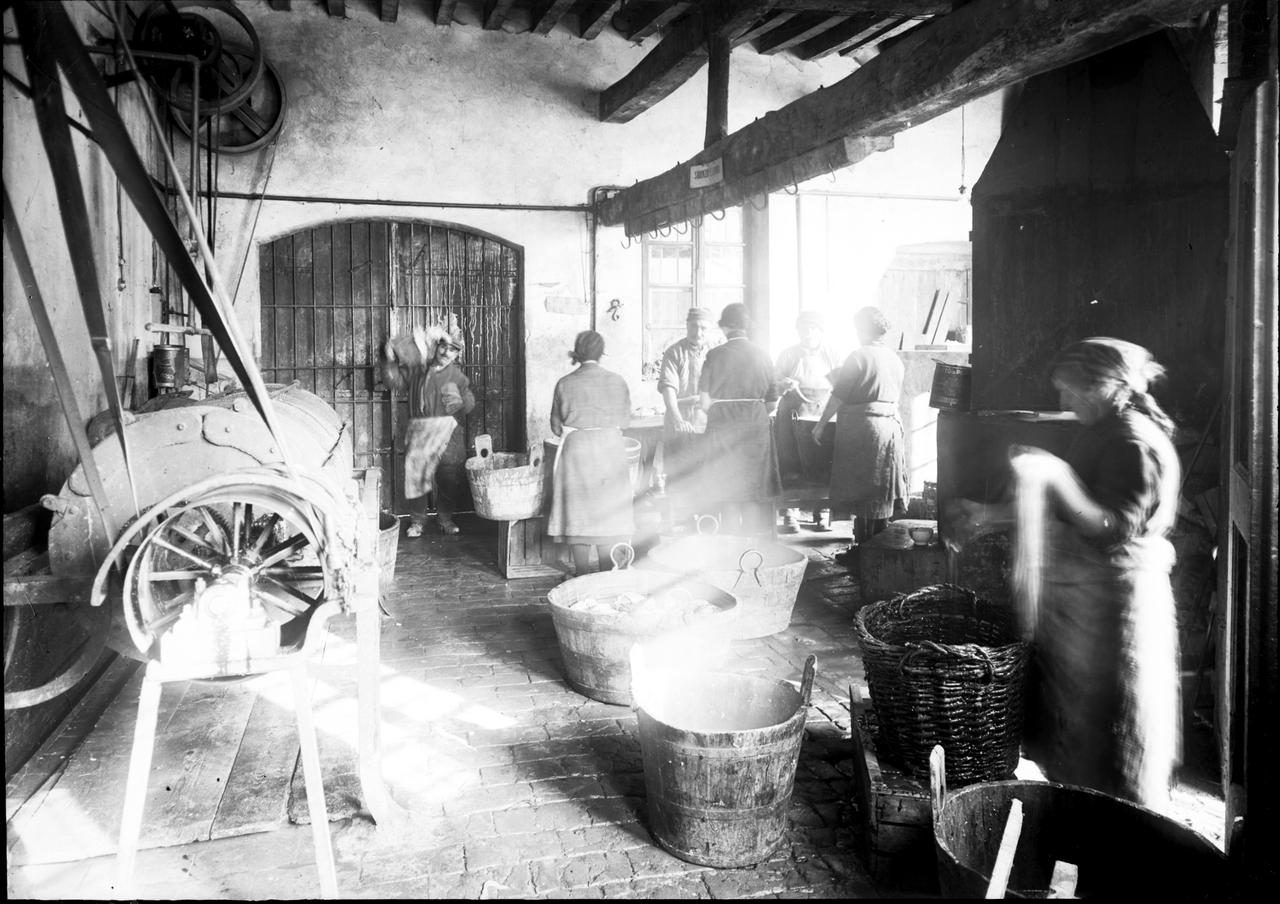

Photographs: Bruno Vaghi, of the Prosciuttificio Boschi family business in 1930, from the University of Parma

Photographs: Bruno Vaghi, of the Prosciuttificio Boschi family business in 1930, from the University of Parma

According to supporters, Parma ham is a traditional, natural product that is produced using centuries-old methods, which enables Italian pig farmers to make a decent living from a premium product.

For them, the ham is a central part of Italy's gastronomic heritage - linked to artisanal production, regional identity and culture - and intrinsically connected to another iconic Italian foodstuff, Parmigiano Reggiano, (Parmesan cheese) that’s also produced in the region. In a tradition still practiced today, whey created during cheese production is often fed to Parma piglets - an example of the product's sustainable roots, say supporters.

Make change possible

Investigative journalism is vital for democracy. Help us to expose injustice and spark change

Click here to support usYet critics paint a different picture, one involving factory farming, allegations of widespread cruelty and suffering, and an industry that’s become part of the much wider industrialisation of livestock production taking place globally. In recent years the sector has been rocked by a number of scandals that have appeared to reveal poor welfare conditions and bad practices on some farms producing Parma pigs.

Although industry chiefs acknowledge that in some cases the standards found were unacceptable, they insist these were isolated examples rather than representative of the industry as a whole. (There have also been accusations that some of the campaigners' evidence may have been misrepresentative and designed to harm the industry financially.)

Earlier this week, in the latest salvo, Eurogroup for Animals, a Brussels-based consortium for European animal welfare groups, published new evidence that it says again highlights concerns over the hidden face of Parma ham production. The graphic undercover footage, obtained at four intensive Italian pig farms in the Lombardy region, appears to show animals housed in dirty, overcrowded or barren conditions, evidence of inadequate veterinary care and poor hygienic standards.

At one industrial farm, capable of housing up to 3,000 pigs, according to Eurogroup for Animals, a log book written by undercover investigators recorded the following findings:

“Animals with untreated wounds found in both weaning and fattening facilities. Absence of adequate environmental enrichment. Excessive stocking density especially in the fattening units, which in some cases produced critical conditions for the animals. Some animals were very dirty and in some cases had serious injuries, with untreated and evident lacerations of the anus and of the tail. Carcasses of dead pigs were stored outside the building, in close contact with one of the sheds.”

“These pigs are not being treated as sentient beings, but as mere meat-producing machines”, claims Sean Gifford, Head of Campaigns at Compassion in World Farming, a UK member of the Eurogroup for Animals alliance. He believes the conditions seen here are echoed at a number of other farms supplying Parma ham. “These poor standards of welfare are completely unacceptable...in the pursuit of cheap meat.”

A quality product, say farmers

This is not a description of Parma production that farmer Nuno* would likely agree with. A third generation farmer, breeding pigs for Parma and other hams, and cattle for producing Parmigiano Reggiano, the family business started up decades ago, in 1938. Today the farm has 350 sows producing between 8,000-10,000 piglets a year - a medium sized operation.

“In this area we all had a mixed breeding of cows and pigs”, says the farmer, interviewed by the Bureau in his vast farmhouse kitchen. “The whey that was left by the production of Parmigiano Reggiano was given as feed to the pigs, it was [like] sugar for them.” With such a highly protein food the pigs would grow bigger than average, he claims, reaching between 160 and 180 kg in weight. This compares to a normal weight for a European pig of around 110 kg, Farranti claims, adding: “and that’s why the fat pig’s thigh has the characteristic thick strip of fat that keeps the future ham tender and sweet.”

The farmer tells us that pigs destined for Parma ham can be only born and raised in Italy and only from a few breeds that produce a firm and tasty meat. He also says the age his Parma pigs are slaughtered is older than is typical for pigs - at nine months instead of the average of between five to six - in order to have a more mature meat with thicker fat.

When asked why this is, he replies: “Because historically we could kill the pig only in winter, our winter is very short unlike in the North of Europe, that’s why the pig was heavier and old. To preserve the meat with salt we need a firmer and more mature meat.”

Farmers and Parma ham producers insist the secret to producing the ham is the simplicity of the ingredients used; the pig thigh that eventually becomes Parma ham has only salt and no other additives added, apart from, some say, “the crisp air in the hills around Parma city”.

Under industry rules, the ham must be cured for at least 12 months and only after that, and if it maintains the right qualities of smell, will it be branded with a distinctive stamp. This is the ducal crown that is the globally recognised seal of genuine Parma ham.

A porcine business model

Despite the traditions, and the wholesome-sounding air of the production process, Parma ham has become big business (see box). Around 4,000 farms, spread across ten regions, rear pigs destined to be turned into the speciality ham, served by more than 100 abattoirs. The industry employs 50,000 people directly and indirectly. In 2016, more than 11 million pigs were slaughtered, according to industry data.

The sector has around 150 companies dedicated to producing the ham, for both consumption in Italy and export globally. The UK has a healthy appetite for Parma, with imports worth £27.8m in 2015, not far behind the USA, Germany and France, according to industry publications. In the UK pre-sliced ham accounts for the majority of Parma meat sold.

Carolina Pugliese, a professor from the School of Agriculture at Italy's University of Florence, says the industrialisation of Italy’s pig sector began decades ago: “After the Second World War swine breeding - as with all agri-food production - got concentrated in North Italy and went towards intensive farming, as more or less did all the agricultural sector.”

Parma heavy-weights

Parma ham, often perceived as an artisanal product, made by small-scale producers, has become big business.

The ten biggest producers in the Parma Consortium, the official body in charge of regulating Parma ham, had sales totalling over €2bn in 2016, according to industry records (although this may include sales of some other products).

Its top seller, Grandi Salumifici Italiani, started in 2000 and has a number of meat packing plants in Italy, Germany and France that sell Parma ham. It produces and sells delicatessen meat to more than 30 countries. The group, which owns some of the biggest companies in the industry, reported sales of €640m last year.

Italian meat packing plants made the bulk of the Parma ham revenue last year. Alcar Uno began in the late 1950s and has become one of the biggest ham processing companies in Italy, with sales of over €304m last year.

Rovagnati began as a father-son company, producing butter and cheese, before expanding its factory operations to include ham and other pre-sliced meat. Today, Rovagnati exports to the US and a number of European countries, with latest sales totaling more than €200m.

For five generations, Citterio has been a key player in the cured meats industry. The company spent the latter part of the 20th century acquiring family-owned businesses. In 2008, Citterio built a large production facility in Italy to turn out cold cuts to sell mainly to international customers.

Another big player is the producer of Negroni Parma ham, owned by the Veronesi Group, which has interests across the agribusiness sector, including animal feed, hatcheries, farms as well as meat production.

There is no suggestion any of these companies are linked to poor conditions on farms or any other bad practices.

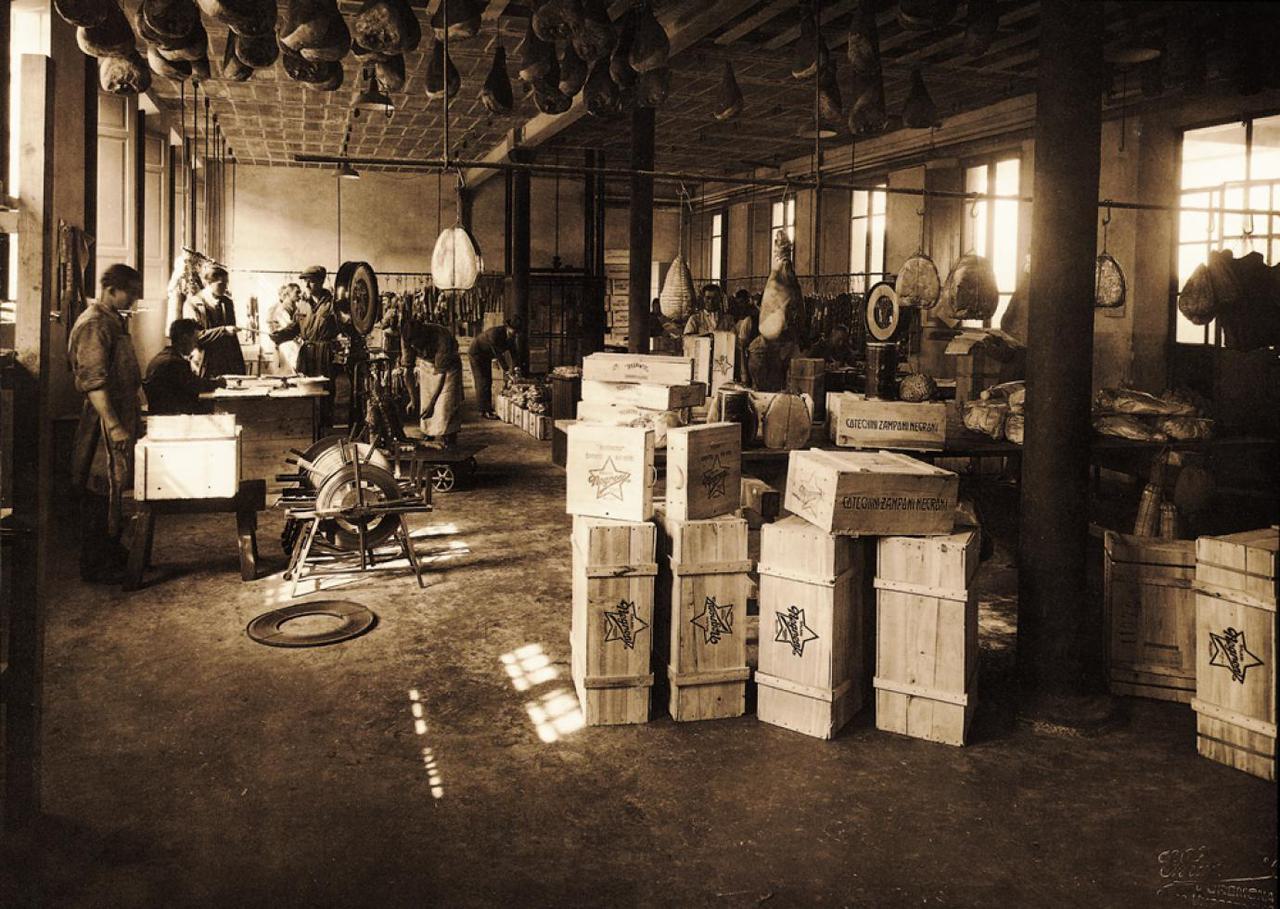

Workers process Parma hams at a factory visited by the Bureau, owned by Galloni

Workers process Parma hams at a factory visited by the Bureau, owned by Galloni

Inside Parma ham production

One major player in the Parma business is Galloni, based in the town of Langhirano, twenty miles south of the city of Parma. The company, which has been in the business in its current form since 1960, produces around 300,000 Parma ham legs a year, which are sold domestically and internationally.

Mirella Galloni, co-owner of the company, says the firm “is one of the biggest producers of Parma ham”. The company distinguishes itself from competitors by continuing to use traditional production methods like salting by hand and seasoning with natural air. At Galloni the curing process is quite long, lasting a minimum of 16-17 months and as many as 30 months. This is opposed to the industry standard of 12 months. “More time... means more taste”, says Galloni, whilst explaining the complex process of effectively seasoning the meat.

The company operates a contract-farming system, sourcing its pork from “less than 100” farms, according to Galloni, with farmers expected to follow highly specific processes dictated by the firm, particularly relating to pig feed. Again, whey from cheese production is utilised, something that Mirella says is advantageous for piglets and that “helps stabilise feed costs, which can fluctuate depending on the price of raw materials.”

A tour of one of the company’s three factories - a giant, shiny warehouse with thousands upon thousands of Parma hams stored on metal racks, each bearing the industry crown stamp - could be said to dispel the notion that parma ham production is, these days at least, an artisanal, cottage industry. Hams from here could end up for sale as far away as New York, where Galloni says the company does brisk business.

According to the businesswoman, much of the international success of the Parma ham brand is down to the industry’s trade body, the Consortium of Parma Ham. The body is charged with overseeing the rules which govern the ham’s production, managing the industry’s public affairs and marketing the product globally.

From a cottage industry to a global brand

In an interview at the consortium’s headquarters, its director Stefano Fanti describes how what was once a local, artisanal product became such a valuable, globally recognised brand: “The market has grown up with the industry and with demand and we had to put into effect a sort of traceability system”, he says. “In the 70s we had the first Italian protection law for Prosciutto di Parma, a state law said what are the pigs [that can] become Parma hams, how to salt the ham, how to cure it”.

The law that defined the production processes in detail had been one of the Consortium’s main goals as far back as 1970. “At the time”, continues Fanti, “every producer had its own way to produce the Parma ham and any of them claimed that was the right way. The Consortium decided to say ‘basta’ [enough] at this confusion and wrote down the rules that then became law.”

In 1992 the European Commission put in place the system of Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) - a certification system designed to protect names and traditions of European foodstuffs produced according to traditional methods in a specific geographical region. In 1996, according to Fanti, Parma ham became one of the first PDOs.

The new PDO status enabled the Consortium to put into practice its strict set of rules for traceability, controlled by an independent body - the Istituto Parma Qualità (IPQ) - that ensures that every pig used is born in Italy, keeps in check the genetics of the breeds used, and checks that feed is composed of the right amount of proteins, fibres and cereals.

In short, the IPQ oversees and “polices” every step of the process. With one apparent and noticeable exception - animal welfare.

Pigs in clover?

Not far from the city of Parma, in the Emilia-Romagna countryside, the Bureau was invited by an industry organisation onto a farm that claims to produce pigs that are turned into Parma - and other hams - for a major Italian supermarket chain. After changing into full body protective suiting, required for biosecurity and hygiene purposes, the farmer leads the way past feed silos and farm equipment before opening the door into one of a series of white-washed, single-storey barns.

Inside, one room contains dozens and perhaps up to a hundred adult pigs. Squealing and grunts fill the air. Each animal is housed in an individual metal cage laid out in rows across the full width of the room, apart from walkways to allow farm workers to pass. These are known as gestation crates, or sow stalls, used to hold animals that have been recently inseminated, and where pigs spend the first four weeks of their pregnancy. There’s room for the pigs to stand up or sit down but turning around isn’t possible, owing to the size of each crate, which isn’t much wider than the pigs themselves.

Such crates were banned in the UK in 1999 and are also illegal in Sweden. A partial ban was introduced in mainland Europe in 2013, but pigs are still permitted to be held in gestation crates for up to four weeks.

In an adjacent room, more pigs are held in similar-looking devices known as farrowing crates. These are home to animals that have recently given birth - around each cage, set on an orange and grey slatted floor, is a small space in which newly born piglets can move.

Most of the adult pigs are lying down, with piglets feeding and scurrying around. Metal bars prevent the adult pigs from moving into the piglets area, to help avoid crushing. Again, the adult animals cannot turn around, but can reach into a feed tray situated at the end of each cage. Farrowing crates have been outlawed in parts of Scandinavia and in Switzerland, but are legal elsewhere.

The farmer shows us into a third room in the complex, where groups of half a dozen or so pigs are housed in a series of identical square pens. Some pens are bare, with no visible straw or bedding, wooden floors and a single, swinging “enrichment” toy hanging from a metal chain. This is to give the animals some entertainment.

Pigs in a stall on a farm producing pigs for Parma and other hams visited by the Bureau, with a single toy hanging in the middle of the stall

Pigs in a stall on a farm producing pigs for Parma and other hams visited by the Bureau, with a single toy hanging in the middle of the stall

It is conditions similar to this that could be seen by some to fuel criticism of Parma ham production, and intensive pig farming in general. Farm animal campaigners say keeping pigs in cages deprives them of many of their natural behaviours, with little scope for exercising, foraging or socialising. They are equally critical of pigs housed permanently indoors in barren pens, and say “enrichment” toys are inadequate for meeting pigs behavioural needs.

As many as 250 million pigs are reared annually in the EU. Welfare groups claim the majority are industrially farmed in intensive conditions. We visited this farm by invitation and the farmer concerned had nothing to hide. In contrast, the farms at the centre of this week’s Eurogroup for Animals investigation were visited in secret, without permission. They had no prior warning that cameras were coming.

Activists say what they found highlights a need for improved pig welfare standards to be implemented, after they uncovered concerns over dilapidated structures, dirty pens, insufficient ventilation, failures of water systems, excessive overcrowding, infestations of mice, food troughs and pens covered in faeces and urine, amongst other poor conditions.

At one farm, undercover investigators reported: “Serious injuries found in many pigs inside the farm. Absence of adequate environmental enrichment. This structure has serious animal management problems: we documented instances of carcases not removed from the pens, left in contact with other animals, in some [for] hours and even days. In several cases animals were found in an agonizing state, left without veterinary care for hours and days. In other specific cases very severe untreated rectal prolapses were observed.”

At another farm, investigators reported finding: “Sick and suffering animals left agonising inside their pens. In one case a weaned piglet remained stuck inside the food trough, lying on his back, unable to free or defend himself, and can be seen in the footage squealing, defecating and urinating on himself and on the pen mates.”

Varied reactions

Paul Roger, a vet with the UK-based Animal Welfare Science, Ethics and Law Veterinary Association (AWSELVA), viewed some of the footage released this week by Eurogroup at the Bureau’s request. He expressed concerns at some of the conditions uncovered.

“It is grim. We keep pigs in similar conditions in the UK but I would say we pay more attention to their welfare and management. I can’t think of any farm that could be successful in the UK running that kind of attitude towards the animals. There are clear signs of poor stockmanship, and a failure to satisfy the animals' basic needs”, he said.

This is not the first time questions around conditions in pig farms supplying the Parma ham market have been raised. A string of investigations by animal welfare groups have taken place in recent years.

Perhaps most controversially, in 2017, pressure group Essere Animali released pictures secretly recorded over a six month period at one farm in which workers were filmed apparently moving animals out of pens using sticks, lifting them by their legs and throwing them on the floor. Dead and apparently sick animals were filmed left in corridors.

The Consortium’s Stefano Fanti says that, in matters regarding animal welfare, the organisation refers to existing European rules which are mandatory for all breeding farms. He accepts there may have been shortcomings in standards in some cases previously but believes these were ‘bad apples’ rather than representative of the industry as a whole.

Nevertheless, last year’s revelations prompted the Consortium together with CRPA (Research Centre on Animal Production), Milan University, National Breeding farmers’ Association and other research centers to begin developing welfare guidelines - due to be rolled out in the next couple of months, according to Fanti - including leaflets and training sessions for pig breeders that highlight ways to improve welfare.

“We can’t afford for consumers to see those images”, he says, adding that the Consortium asked for “immediate interventions” from veterinary officials when the evidence went public. The organisation says, however, that it is not a regulatory body and cannot intervene directly.

In a statement addressing this week’s campaign footage, the Consortium said: “In a smear campaign against Parma ham by, for some years now, some animal welfare organisations who regularly spread shocking images to convince the consumer not to buy our product any more. The Consortium always condemns any violation of the most elementary animal welfare standards that represent a criminal act, intolerable in a civilised society, but we can not tolerate those who improperly use our fame just to get more visibility.”

The Consortium added: “It is not credible that deplorable conditions shown in the images have escaped the eyes of the official vets in charge of control in the breeding farms. Animal welfare, we have to remember, is regulated by a European law valid in all EU-countries and the control is up to the Ministry of Health through the National Veterinary and local service.”

The Consortium added that this was a blanket allegation to attack the reputation of Parma ham and that none of the 145 producers or the Consortium had ever been denounced for animal welfare breaches.

The economics of Parma pig farming

For some, standards in farms supplying to the Parma market isn’t just an issue of ethics and animal welfare, but economics. “Keeping a high standard is vital for Parma ham and for the food industry in Italy”, says Luca Ferrari from the workers’ Union Flai CGIL, “otherwise we couldn’t compete with foreign [imported] pigs”.

Professor Pugliese, for her part, says: “The quality of the meat is high in Italy so is the food security, we have more controls than anybody in Europe. Today [amongst] the main goals is to meet with the higher sensibility of the consumer on animal welfare.”

This week’s revelations will not be welcomed by pig farmers, however, some of whom say that despite the success of the Parma ham sector, profits have not always found their way down to those breeding the livestock. During recent years, prices crashed, due, in part, to overproduction.

“The last ten years for pig breeders had been a disaster, the prices were too low. It was more expensive to produce a pig than to sell it”, says Luca*, a farmer based in Pavia who owns 350 breeding pigs producing around 6,000 piglets each year. “Half of the breeders in this area went under the regime of ‘soccida’ [a system where breeders don’t own pigs, instead fattening them under contract to large companies]. Only a few of us independents survived. Since this year we see some light at the end of the tunnel.”

Pigs in a stall on a farm producing pigs for Parma and other hams

Pigs in a stall on a farm producing pigs for Parma and other hams

Back in Langhirano, there are some signs that welfare is beginning to creep onto the agenda. Mirella Galloni tells us that part of her company’s supply chain is now experimenting with ways to address welfare issues.

“Nearly all Parma farms are intensive, and pigs can be aggressive”, she says. But she adds that it is possible to manage intensive farming in an ethical way. “You have to create entertainment, to support social life in the group, such as balls made with paper.”

Header photo taken from filmed footage by Bureau staff

*Names changed at the request of farmers