Huge disparity in how police use law to protect women from violent partners

Following the trial of serial killer Theodore Johnson, concerns surface about scheme designed to warn others of violent partners.

Those asking for information about their partner’s record of domestic violence are 10 times less likely to receive it from police in some parts of the country than others, new analysis by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism has found.

Clare’s Law - the scheme designed to help people find out if their partner has a history of violence - was heralded as a potential life-saver when it was introduced in 2014 following the murder of Clare Wood by her violent partner, who was known to police.

The law allows people to ask the police for information about someone they know and also enables the police to proactively warn people who they believe may be in danger.

Yet the Bureau has found huge disparities in how forces release information to those that apply, with some forces disclosing to less than 10% of applicants, others to more than 70%.

Clare’s father Michael Brown told the Bureau he was “very disappointed” to hear that some police forces aren’t using the scheme as often as others. “We didn’t run around for five years to get the law in place just for it to be ignored,” he said. “It seems like some police forces just don’t put domestic violence high up on the list.”

MP Jess Phillips who is on the Women and Equalities select committee told the Bureau: “the inconsistencies must be investigated and a level playing field must be reached. If we are going to make new legislation, we have to make sure it isn’t just nice-looking law, it has to mean something on the ground.”

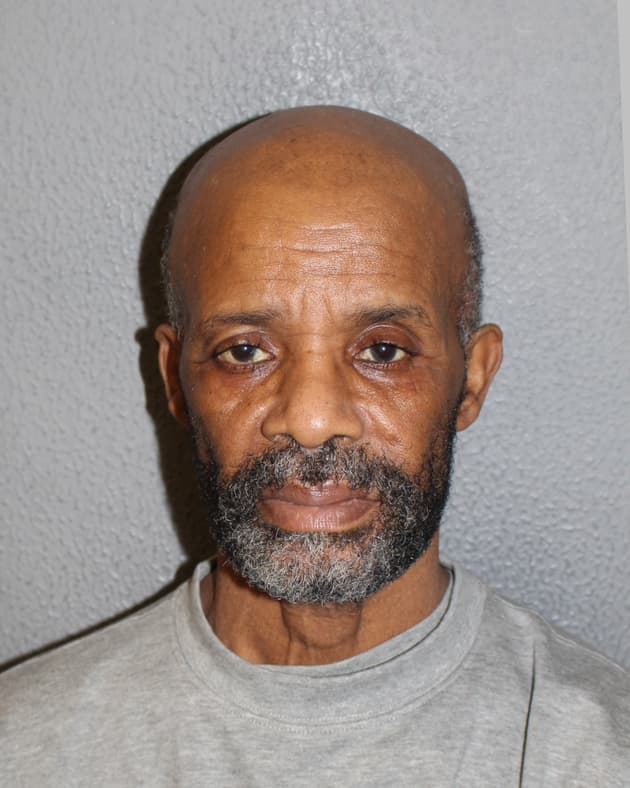

The findings come days after serial killer Theodore Johnson was sentenced to life and ordered to serve 26 years for the murder of his ex-partner Angela Best. Johnson had already killed two other women: his first wife Yvonne Johnson and, years later, his partner Yvonne Bennett.

Variations across the country

The Clare’s Law disclosure scheme encompasses two elements: the right for members of the public to ask the police for information on their partner’s offending history (right to ask), and an element which allows the police to warn those who may be at risk (right to know).

The Bureau’s analysis reveals that take-up of the scheme varies across England and Wales. The number of applications from the public to find out about a partner’s past - per 100,000 - are 15 times as high in some areas as in others. The number of applications from the authorities to warn partners proactively are 30 times as high in some forces as in others.

Make change possible

Investigative journalism is vital for democracy. Help us to expose injustice and spark change

Click here to support us Michael Brown, Clare's father, campaigned for years to get the law passed.

via First Minister of Scotland

Michael Brown, Clare's father, campaigned for years to get the law passed.

via First Minister of Scotland

There is no set format for how police make decisions on Clare’s Law applications. The level of seniority needed for an officer to sign off disclosures varies across the UK. Some forces take decisions to safeguarding boards where social workers, healthcare professionals and others consult on decisions. In other cases, police have set up their own ad-hoc decision-making panels specifically to look into requests.

The Bureau also found disparities in the rate forces disclose information under both elements of the scheme. Disclosure rates range from 3% to 98% for “right to know”, and 7% to 76% for “right to ask”.

For instance, Cumbria and Bedfordshire forces cover populations that are roughly the same size, however the Cumbria force made 226 proactive disclosures last year compared to just one disclosure by the Bedfordshire force.

Those two forces had similar numbers of applications from members of the public under the ‘right to ask’ element, but in Cumbria disclosures were made 76% of the time, while in Bedfordshire information was shared in just 8% of cases.

Sergeant Colin Nelson, from the Bedfordshire police’s Public Protection Hub, said: “We recognise as a force the ‘right to know’ element to Clare’s Law has been underused in Bedfordshire. We are working to improve the knowledge and understanding within our workforce, and increase its use to provide early intervention and help protect the most vulnerable from harm.”

Theodore Johnson was sentenced to life and ordered to serve 26 years for the murder of his ex-partner Angela Best.

via The Metropolitan Police

Theodore Johnson was sentenced to life and ordered to serve 26 years for the murder of his ex-partner Angela Best.

via The Metropolitan Police

“Justice by geography”

Professor Sandra Walklate, from the University of Liverpool, looked into how the scheme is working across the country. She told the Bureau it is a case of “justice by geography”.

“There’s variation in what forces share and variations in the extent to which this is a proactive process in the first instance”, Walklate explains. “I guess some areas will have put a lot more effort into advertising or promoting the scheme.”

“It is all driven by different forces’ priorities and resources at a local level. Some forces have suffered more than others in austerity, and these kind of schemes cost”, she added.

This was echoed by retired detective superintendent Phil Owen, one of the driving forces behind the creation of Clare’s Law. He told the Bureau there is no funding available for police to process applications. Requests from the public need to be made in a face-to-face meeting, which could be impeded by staffing issues.

Owen now helps train police forces across the country on the use of the disclosure scheme, but he says he notices big differences in the rate at which forces disclose information.

“At Greater Manchester police, we were ‘lawfully audacious’, meaning if ever there were some concerns, we would disclose information. We’d rather face investigation by the Information Commissioner’s Office than face an inquest. But some forces are more cautious”, Owen said.

A spokesperson from the domestic abuse charity SafeLives said: “Clearly, the use of Clare's Law and other powers available need to be of a consistently high standard across the country. A woman, wherever she is, whoever she is, should be kept informed if she begins a relationship with a predatory perpetrator that puts her at risk. This is currently not the case.”

“We need the police and other agencies to be brave and proactive in how they share information to properly understand the risk someone poses, and monitor dangerous men.”

Official reports in 2016 and 2017 have echoed these concerns and pointed out delays and inconsistencies in the way forces disclose information.

Last month, the Bureau revealed that another domestic violence law, designed to tackle coercive and controlling behaviour, was not being actively used by many police forces.

Six police forces in England had brought five charges or fewer since the coercive and controlling behaviour law was rolled out in December 2015.

Further research by the Bureau revealed councils across England cutting funding for domestic violence refuges. Funds had been reduced by 24% since 2010, according to data compiled through Freedom of Information requests.

Get the data

Access the data behind the story to find out the information relating to the police force in your area.

Access it hereMain picture via Juliet Nagillah/TBIJ.

If you need to talk to someone about domestic violence contact Women's Aid/Refuge free helpline on 0808 2000 247. If you are in immediate danger, call 999.