No place of safety

The inside story of how women fleeing domestic violence lost their refuge

It was a little after one in the morning when Susan’s world came crashing down for the second time.

She was woken in the middle of the night by commotion from the room above her. A huge chunk of the ceiling, sodden with heavy rain, had come tumbling in. It brought dirty water flooding into the building.

Bleary-eyed and scared, Susan wandered out to the hall. The other residents of the building, seven women ranging in age from early twenties to late fifties, had gathered their young children and made a makeshift shelter in the communal living room.

“We were terrified, we were sleeping on mattresses on the floor”, Susan recalls.

The women say they had been complaining about leaks for weeks, as well as a malfunctioning fire alarm and an infestation of mice and insects.

This was not just another case of a rogue private landlord. These women were living in a domestic violence refuge located in one of the most affluent boroughs in the UK, Kensington and Chelsea.

This was a place where these women, each fleeing horrific violence at the hands of their former partners, hoped they could find support and protection.

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism has been following the stories of six of the seven women housed in that shelter for the past three months as they have been buffeted around the social services system, from hotels, to council meetings, to lonely flats. The seventh woman has dropped off everyone’s radar.

We have also found that local authorities all over England have cut their funding for women’s refuges, by 24% on average. In Kensington and Chelsea, however, the cuts are even more stark, with refuge funding plummeting 45% over the same period.

In the weeks following the emergency the women say they have felt ignored, housed in unsuitable premises and have been left insufficiently unsupported. Out of those we interviewed, two have been hospitalised with suicidal thoughts and two are living on the floors of friends and family. One woman has been located by her ex-partner.

These are their stories.

Nowhere to turn

The morning after the ceiling collapse, Susan and the other women gathered their belongings together. However, they say they struggled to get anyone in authority to take notice.

The refuge was managed by a charity, Hestia, which also offered support services. A housing association, Notting Hill Housing Trust, owns the building and provides maintenance, in response to call-outs from Hestia.

Support workers were on site during the week; at the weekends a senior manager was on call.

When the roof collapsed during a weekend the women say they could not reach their usual support workers, although the on-call manager did pick up the phone and alerted the Fire Service and the housing trust.

Six hours later an electrician turned up. He took one look at the water pouring through the walls and plug sockets and he said “I cannot, I cannot turn the electricity back on in this house, I cannot do it, because this place will light up just like Grenfell Tower”, Susan adds.

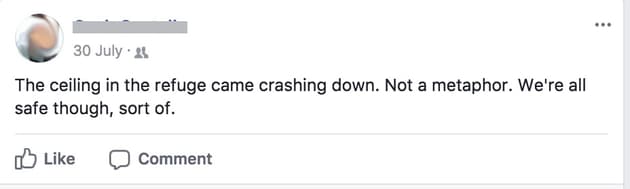

Frustrated by the reaction of those tasked with supporting them, the women set up a Twitter profile and posted on Facebook, desperate to get the help they wanted.

The desperate Facebook post sent by the women just after the collapse

Facebook post from Refuge Women, altered for safety reasons

The desperate Facebook post sent by the women just after the collapse

Facebook post from Refuge Women, altered for safety reasons

Commiserations and words of support rolled in from the general public. But as time went on, over weeks and months, the women would find themselves battling alone, fighting for an appropriate safe place to stay.

No place to call home

Two days after the roof fell in, I meet the women on the steps of the Kensington and Chelsea council buildings. Three of the women wait nervously on the steps of the civic centre. Jessica, an older woman, leans her arm on her walking stick to steady herself as she fishes out her mobile phone. She shows image after image of her room at the refuge, covered in rubble and dirty water.

Another of the women, Carrie, smooths the hair of her six year old daughter. The council has told her they might be moved 12 miles away to another area of London. Carrie is unsure whether or not to go. “We said, we don’t want to leave our schools or the support networks we’ve built up”, she says.

The council is telling some of the other women, including Susan, that they should move back into the refuge. While they were explaining this, in the council offices, the ceiling of Susan’s room caved in. Now she is not sure where she will go. “I’m just so nervous”, she says, tears falling down her cheeks.

In the end the council does not send the women back to the refuge to live. Instead, they are allowed in just to collect up their belongings. They have to gather up their few things, putting them in black bin-bags to take away.

Belongings in bin bags

Illustration by Ella Paton

Belongings in bin bags

Illustration by Ella Paton

It is another two days before I meet the women again. This time they have been housed in Travelodge hotels. Some are in the same hotel as traumatised survivors of the Grenfell tower fire, which broke out in the early hours of 14 June. The lobby and restaurant of that hotel becomes a gathering place for them to share their stories.

Fatma had been at the refuge for around a month. She left her abusive husband after years of torment, taking her young son with her.

At home Fatma had learnt to stifle her screams of pain during attacks so as not to wake her sleeping child. Last night, in the hotel, she woke him up with her sobs. The stress had become too much for her.

The women say they have been told that they will be moved on soon. For now, their hotel rooms will be paid for.

Fatma fears that she has nowhere to go. “I am thinking maybe we will go and sleep in Chelsea Hospital lobby,” she says, her eyes tired. “I have my son’s pushchair and his cosy coat because I don’t want him to be cold. I think I will take him in his pushchair and sit in the lobby. If someone asks me, I will say it is an emergency I am waiting for something. This is my plan”, she says, breaking down in tears.

In the room next door Susan has laid the few possessions she salvaged from the refuge carefully in the corner. They are paintings done by her recently deceased father, some splattered with patches of water damage. She did not manage to get anything else. Fatma has lent her a t-shirt because she has no change of clothes of her own. These days her entire life can be stuffed into a couple of bin bags.

She is furious. Notting Hill Housing have tweeted, saying: “The residents have all been provided local accommodation until they can return sometime this week." Susan using the women's group account, has responded with one word: “Lies.”

A tweet reads "Lies", as the response from Refuge Women to the council

A tweet from Refuge Women

A tweet reads "Lies", as the response from Refuge Women to the council

A tweet from Refuge Women

“One of the things my ex-husband used to do, he’d get mad at me and tear up my things and break my things and stuff like that. It felt like as soon as I had left that place and managed to get the things I cared about most and wanted to keep the most, here I am in this women’s refuge and it's got destroyed as well and I’ve just got nothing left.”

She takes out her phone and plays me a recording. Out of the tinny speaker comes her voice, crying. She is apologising for the fact she asked for the train fare so that she could scatter her father's ashes. The other voice, that of her husband, is gruff and angry. Suddenly he is yelling in a voice filled with rage: “Oh my God, leave me alone!”

“He screamed in my face”, Susan explains as the man’s voice bellows in the background.

Things had not always been bad. “He started out as this really amazing person and we had so much in common, funny, articulate, all those things”, she says. Six months into their marriage, however, the mask slipped. Her partner abused both prescription drugs and alcohol. As well as the screaming arguments he controlled her access to money, making her account for every penny she spent.

Then there was the physical violence.

“There were times where he had choked me, grabbed me by the neck and thrown me down on the ground. There were times when he’d taken a telephone charger cable, and the metal end of the bit, and whipped me with it, hit me in the face, I had welts all over my face, one across my cheek, I had to lie about what had happened.”

One day, after she had been woken in the night by her husband dragging her off the bed and punching her repeatedly, she decided she had to leave.

“I called a domestic violence helpline and I said that I need help now. The support worker wanted to put me in a refuge that day, which didn’t happen…it took longer than that…she said ‘call as many friends as you can’, she said ‘I know it’s embarrassing, call ‘em, call ‘em, just see who will pick up, and that’s what I did.”

Susan ended up spending three weeks on her friend’s floors before they found a refuge for her. Her situation is far from unique; a recent report from the charity, Women’s Aid, found that because refuges are full to capacity women spend an average of one to two weeks waiting for a place to open up. In one case, a woman waited six months.

The Bureau surveyed 40 refuge managers across England; 95% of them told us that they had turned women away in the last six months because they either did not have the space or they no longer had funding for the support services to meet the woman's needs. While women wait for a space to become available in a refuge, they remain in danger. One woman we spoke to said that the police had been called out to her flat four times while she was waiting to get into a refuge.

Safe at last?

When she arrived at the Hestia refuge, located on a quiet side street in Kensington and Chelsea, Susan thought she was safe. However, the refuge was hardly homely. Mice and insects infested the eight bedroom building and brown patches of damp stained the ceiling. Susan and the other women complained.

“I’ve complained about leaks, I’ve complained about cockroaches. I’ve complained about mice, nothing was done – over and over and over again”, she says. Hestia says that it did respond to the rodent infestation and had asked the residents not to leave out food. It also acknowledged that a report was made to the Housing Trust about a fire alarm going off, but that an electrician attended and carried out “a full repair”.

In general, refuges are funded through a complicated combination of housing benefits, which pay for the buildings, and local authority funding which pays for support services, such as support workers, child workers, language specialists and counselling services.

In this case, the room rent for the women was paid through housing benefits. The support workers and running costs came from local government funds.

The women are not impressed with the help they received.

Hestia, the charity that managed and ran the support services provided in the refuge, provided only basic support. The women said that they arranged their own counselling services through their doctors, where they were often put on waiting lists and delayed as medical records were transferred from their homes across the UK.

The staff were friendly, the women say, but very young and inexperienced. Carrie remembers her first day in the refuge. “I was met at the tube station by my support worker who was pleasant enough”, she recalls, pushing her hair back off her face.

However, Carrie says the support workers weren't able to help the women fill in basic forms. Hestia, for its part, says that all workers are fully trained and that no such issues have been raised with its local manager, adding that the refuge had a dedicated Children and Family worker.

“There is no counselling or anything in this refuge. There’s no provision at all. Often you can’t even reach a support worker. Over the weekend, apart from the emergency on-call person, we weren’t able to get hold of our key workers.” Carrie added.

Hestia is a charity which was set up in 1960. It claims to be the largest provider of domestic abuse refuge services for women and children in London, with 32 refuges across the city. The organisation has held the contract to provide domestic violence services in Kensington and Chelsea for many years. In late 2015 they were called to tender again.

Got a Story?

We welcome tip-offs from the public and we always protect our sources

Find out how to work with usIn response to a Freedom of Information request the council said it had cut its spending on domestic violence refuges by 45% since 2010. This meant, in turn, that Hestia had to reduce its budget in order to win the contract. Hestia said, in a statement: “All supported housing services for all client groups have seen significant cuts to funding over the past decade, including refuges for women and children fleeing domestic abuse.”

In council paperwork seen by the Bureau, the charity agreed to drop its budget by 14% to get the current contract. Officials note: “The contract value, under the Hestia proposal, would reduce the RBKC contract value from £184k to £158k, delivering a saving of £25k per annum.” Hestia says that the 2017 contract has risen in value.

The housing association which was responsible for the upkeep of the building, Notting Hill Housing Trust, had also experienced budget cuts in recent years. The company dropped its budget for social housing from £4,876 per unit in 2014/15 to a budget of £4,267 in 2017/18. The trust told the Bureau, in a statement: "Over time, we have sought to become more efficient, for example, by reducing management costs, so that we can make our funds go further and ensure we have more money to reinvest in our core purpose - providing more homes for low-income Londoners."

In the year 2016-2017 there were 174 enquiries or complaints about Notting Hill Housing Trust to the Housing Ombudsman Service.

The company also missed its target for responding to complaints in time. The trust acknowledged both these points and said it was "working to reduce the time we take to respond to complaints", adding that the number of complaints where the Ombudsman had contacted the trust was 61 in total, a smaller figure.

The council has been earmarked to share a slice of £489,643 funding from the Department for Communities and Local Government, which was awarded to Kensington and Chelsea, Westminster and Hammersmith and Fulham councils. However these funds will go specifically to a specialist refuge for women from Middle East and Afghanistan with high mental health needs and immediate and short-term refuge accommodation for rough sleeping women facing domestic or sexual violence.

It was in this context that Susan and the other women asked for shelter and then found themselves in yet more trouble.

Nowhere to go

Weeks pass and the refuge is still uninhabitable.

One by one the women are rehoused, some in bed and breakfast accommodation, whilst some others are offered council flats. But all options are problematic.

Jessica is in her fifties and has health and mobility issues, walking with a stick. The ceiling fell in first in her room in the refuge. Luckily she was in hospital when it happened.

A video on her phone documents the tiny room, the single bed, swamped by heavy chunks of damp ceiling.

Kensington and Chelsea council have a duty to house all the women, but they have not found any spaces for them in the borough. Instead, Jessica is offered a tiny, unfurnished studio flat elsewhere in London. She is not happy.

“I just got the keys for the temporary accommodation, but it is not suitable at all. I have a disability, this is a basement and there are lots of steps, so it is hard to get to the flat”, she explains, her voice tired and distant as she talks to me on a phone line.

Jessica walks with a stick and the eight or so steps down to the front door of the flat are too much for her. In addition, she is scared that the front door leads straight onto the road. “I don't feel safe”, she explains.

Too scared to stay, Jessica has instead been staying with family.

Carrie and Fatma were also offered flats. Both were unfurnished and they have no idea how long they will be staying there. Fatma spent five nights without a piece of furniture, her son slept in his pushchair and she made a bed on the floor with a towel, using his disposable nappies as a pillow.

The day she got the keys to her studio council flat Carrie got on her hands and knees to scrub dried faeces left there by previous occupants, off the walls. Days later, after making preparations to get her daughter into the local school, she found out she would only have the flat for a few months and would then be moved again.

No place of safety

But beyond the discomfort, three of the women from the shelter have been in real danger since leaving.

Fatma was sent to a flat in a neighbourhood where she feels at risk. She is not from the UK and the area is full of people from her home country. She believes that makes it likely that her violent husband will find her there especially as his job regularly brings him to the area.

“So I don’t talk much when we are out”, she explains, “even this main road we have to walk to the train, every day I am scared my husband will see me.”

These days she mainly stays in and keeps herself to herself, except for three days a week when she takes three trains to take her young son to his beloved nursery school. It is costing her more than £8 a day, money she cannot afford.

She has, however, little choice. Despite protesting to Kensington and Chelsea council that this area was unsafe for her, she was given the option of taking the flat or refusing it and making herself “intentionally homeless” and therefore no longer the responsibility of the council.

Another of the women, Roxanne, is in bed and breakfast accommodation. Her violent ex-boyfriend has tracked her down, but she is too exhausted to move again. “Besides, I think at least there are people here. If he comes I can shout and the manager or someone might come, if I am in a flat alone there is no one to help”, she says.

Without a social worker she has been asking Hestia for help, but her ex-boyfriend found her. She eventually reported it to the police.

Another woman, Mel, was caught in a bind. If she accepts another council flat then she will lose the flat she had before she had to flee to the refuge. She had lived there for a long time and was working towards having the Right to Buy. “I would have had to give up my tenancy. I have had it for 18 years and didn’t want to lose it”, she says. Now she and her two small children are sleeping on air mattresses on a friend’s floor.

“We’re stuck in the middle”, she explains, “the council and the police have refused to help me and insist there is no danger, even though my ex-partner was seen outside my house two weeks ago.”

Susan is also still feeling let down by the lack of support. She was also placed in bed and breakfast accommodation, this one run by men and with a lot of male clientele. One day, as she was getting changed, she saw a man photographing her through the window.

She called Kensington and Chelsea Council and told them she was very uncomfortable there.

“One of the housing department people said 'oh, we’ll get in touch'. Well, four days later no one had got in touch. One of them said, 'unless there is a police report of what happened, we’re not moving you'. He was even questioning me like, well, if this happened you would have gone to the police. He goes: ‘well any normal person would report it right away’. It was like the worse thing you could say.”

Eventually Susan filed a police report. While she was at the station she says that a police officer called the council. They finally took note; less than a week later she was placed in a small flat elsewhere in London.

However, the experience took its toll.

“I think at one point I hadn’t slept for four or five days, I ended up going to the hospital for urgent care. I literally broke down crying, I was like, 'I need help, I need supervision, I can’t do this any more.'” For Susan bed and breakfast accommodation didn't work.

Hestia’s own survey of their clients found that 49.5% service users said they would feel “scared and unsafe” in bed and breakfast accommodation, while 13% said they thought it would put their recovery process back by months.

Aftermath

It has been nearly three months since the roof fell in.

None of the women are happy with the way Kensington and Chelsea council have responded.

The council told the Bureau in a statement:

“Women who have survived abuse need the best possible care and services to help them rebuild their lives, we know that and we understand that. More money than ever is being invested in these services and the contract given locally to the domestic violence charity, Hestia, was done so through a competitive and fair process in line with all other refuge services across West London. The way in which the service is delivered is the responsibility of Hestia and the maintenance of the building is managed by the owners, Notting Hill Housing Trust. The Council acted immediately to help Hestia temporarily relocate the people at the centre to similar premises where there was room and at short notice. We expect the very best from this service, we are investigating, and will take further action if required.”

Of the six women we’ve been following, only Carrie is secure. She managed to find a private rental flat with a cheap enough rent to be just about affordable. Her young daughter gives me the grand tour. Her favourite part of the tour, is to show off the toilet. “We didn’t have our own toilet in the refuge”, Carrie explains.

Fatma and Susan are now in council flats, but they have no idea how long they will be able to stay there. Jessica and Mel are living on the floors of friends and family. Roxanne is in bed and breakfast accommodation, hoping that her ex-boyfriend does not find her again.

It has not been the secure, happy ending they had hoped for when they left violent and dangerous homes. Some of the women have even considered going back to their abusive partners, that the sacrifice of being beaten up is worth it to have a roof over their heads.

“We said, 'do we go back and risk our lives or not'”, Susan explains. “These are the options we have to weigh, do I go back and at least it is stable and I can save enough money to get out and be more stable but I might also be killed by him before that happens, or do I stay in this situation where I am starving myself and the stress is unbelievable, we’re moving from place to place, losing our things, everything we own?”

“You just have to make that decision, do you keep fighting or do you give up? And there are so many people that would give up. We had each other and that is the only reason we didn’t."

If you need to talk to someone about domestic violence contact Women's Aid/Refuge free helpline on 0808 2000 247. If you are in immediate danger, call 999.

All names in the article have been changed for reasons of safety.

All illustrations in the article are by Ella Paton, a member of the Bureau Local network. Her work can be seen at etsy.com/uk/shop/Viewfi…