Caught in the crossfire

Civilians are bearing the brunt of conflict in Afghanistan

Hamid Gul just wanted his family to be safe.

The 18-year old shopkeeper lived in Lashkar Gah, the capital of Afghanistan’s much fought over Helmand province. After his father was killed by an improvised explosive device (IED) in 2013, Hamid and his older brother, Mirwais, had to take care of his mother and younger siblings.

A focus of Taliban violence for many years, Lashkar Gah became much more dangerous after the US handed over primary responsibility for the security of Afghanistan to the Kabul government at the end of 2014. Not long after, districts in northern Helmand began to fall and Lashkar Gah looked in a perilous situation.

In 2016, Hamid sent his mother and siblings back to their family home in the district of Sangin. The insurgents had swept through most of the district earlier that year; this meant Hamid’s family home, now behind Taliban lines, would no longer be caught in the crossfire. Hamid stayed in Lashkar Gah to earn enough money to provide for the family, while Mirwais continued his studies at the city’s university.

By the start of 2017 the Taliban was pushing hard to take Sangin city’s district centre, a fortified compound which housed the local security and administrative officials, just a few miles from Hamid Gul’s family home. The compound was the only thing stopping the Taliban from claiming the whole district as their own. The US, which had lost at least 70 of its own troops keeping Sangin out of insurgent hands over the years, scrambled to respond with scores of airstrikes.

Hamid was convinced that his family were still safer behind Taliban lines than in Laskhar Gah, one of the Taliban’s prime targets. But on the morning of February 10 2017, he got an unexpected phone call from a neighbour in Sangin: the family’s house had been flattened.

In that one night Hamid Gul lost his 50 year-old mother, Bibi Bakhtawara, six brothers and a sister. All seven children were under 16 years of age. Bibi Rahmania, his niece, also died. She was just two years old.

Hamid was not the only person given devastating news on that day. On the same night, a few hours later, a second civilian house, just a few miles away from his own, was also hit. The following night a third one was struck.

To this day, there is no consensus about what happened to those three houses and why. What is clear, however, is that by the end of those three days in early February five women and 19 children were dead, among a full toll of 26 civilians, a Bureau investigation has established.

Three local officials interviewed by Bureau reporters on the ground claimed US airstrikes had destroyed the houses and killed their inhabitants. The United Nations (UN) said the same, in its biannual accounting of Afghan civilians killed in the war, released in July 2017, adding that there appeared to have been no fighting in the area at the time, meaning the attacks may have been pre-planned.

A spokesperson for Resolute Support, the US-led Nato mission in Afghanistan, told the Bureau that after four investigations the organisation could not confirm or deny responsibility for killing the civilians, though he pushed back strongly against the UN’s claims that there was no fighting in the villages at the time. Resolute Support has officially concluded the case as “disputed”, one of four categories for recording allegations of civilian casualties. It was used in this case because Resolute Support cannot decide if insurgents or the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) were responsible for the casualties, the spokesperson told the Bureau.

The fact that no-one has taken responsibility for the deaths of 24 women and children offers an insight into the lack of accountability of America’s longest-running conflict, which it now fights largely from the air under opaque rules of engagement against 20-odd armed groups.

US policy in flux

The US troop presence in Afghanistan - which reached 100,000 at the height of the occupation in 2011 - was slashed to a light footprint of around 9,800 by March 2015, along with around 6,300 soldiers from Nato and non-Nato allies. By this point the US and its partners had stopped fighting the Taliban. The Afghan forces were meant to have assumed primary responsibility for that effort, with Resolute Support troops training and advising them in a non-combat role.

The US was not allowed to take the fight to the Taliban on the ground and they could only carry out defensive airstrikes against the insurgents when they were threatening Resolute Support troops. They could occasionally give Afghan soldiers air support but only to save them from a serious setback, such as a strategically significant base being overrun. By June 2016 the ANSF were struggling to hold the Taliban back and the White House gave the US military permission to expand the scope of its strikes, despite announcing weeks later in early July the US force would be cut again to 8,400 in 2017. The new targeting rules meant it was allowed to carry out strikes to help Kabul’s army and police either take or hold ground from the Taliban and the various other armed groups in the country.

This jacked up the strike rate in Afghanistan. There have been more strikes in the first six months of this year than in all 2015 and 2016 combined. But with a smaller troop presence, on the ground intelligence is reduced. While Afghan security forces do most of the fighting on the ground, in particular the elite Afghan commando units which operate with US special forces advisers, Afghan intelligence analysis “remains a weakness,” according to a Pentagon report.

It recently emerged that through this period US generals have had to get creative in calculating troop numbers to ensure they had sufficient soldiers in the country to do the job without breaking the limit set in Washington. They did not include soldiers on short term deployments lasting 120 days, so hiding an extra 3,500 personnel.

In late August President Donald Trump announced his new strategy for the war in Afghanistan, including an increase in troops of around 4,000 though officials have refused to confirm a specific figure. More trainers and advisers will likely lead to a further increase in airstrikes, with more US troops to call in close air support for their Afghan partners.

US strikes - together with an unknown number of Special Forces on the ground - have also been hitting the Afghan offshoot of Islamic State for nearly two years.

The Taliban, meanwhile, has been carrying out attacks in districts across the country. Civilians getting caught in the crossfire between the Taliban and Afghan security forces is the second leading cause of civilian harm this year. Insurgents are responsible for most civilian casualties but the situation on the ground is confusing and lines of responsibility for casualties can be blurred. In July the UN attributed 10% of civilian casualties this year jointly to both the Taliban and Afghan security forces because monitors could not tell precisely which side hit them in the crossfire.

Collateral damage

Even if the source of the high explosives that flattened their houses was unclear, for Gul and other residents of Sangin there was nothing ambiguous about their effects.

Shopkeeper Fida Mohammad lived in a village just a few miles away from Gul. His village was the second place to be hit during those three days in early February.

His son, Habib Rahman, 21, told the Bureau that February 9 2017 had been an ordinary day. The family ate dinner together and went to bed. Fida Mohammad’s house was an extended building, stretched around a compound. Rahman and two of his brothers lived on one side of the house with their families, Fida and his wives lived on the other side, along with more of his children.

A blast, at about one o'clock in the morning, woke Rahman and the rest of the family on his side of the house. They dashed outside to find their father’s side of the home flattened. They scrabbled through the rubble. Each time they turned up a body they hoped in vain for a sign of life. All in all they lost 13 family members that night, including Habib Rahman's mother and step-mother, as well as his four sisters Amina, 17, Habiba, 15, Najiba, aged eight and Fatima, aged just four. Rahman also lost a niece, Nooria, who was one year old.

The next night, in the small hours of February 11 2017, Haji Mullah Ghafar was going to early morning prayers in the village of Shakar Sheela, just outside of Taliban territory. A local imam, or prayer leader, he was in the mosque when a blast flattened his house.

His 55-year old wife Bibi Sara was killed, along with his nine year-old son, Zia and Freshta, his eight year-old daughter. His grandson, Rohullah, aged just nine, also died.

| Name | Age | Strike location and date |

|---|---|---|

| Nooria | 1 | Chinari, 10 February 2017 |

| Bibi Rahmania | 2 | Mata Lakara, 9 February 2017 |

| Fatima | 4 | Chinari, 10 February 2017 |

| Naz Bibi | 5 | Mata Lakara, 9 February 2017 |

| Mohammed Wais | 6 | Mata Lakara, 9 February 2017 |

| Muhib Rahman | 6 | Chinari, 10 February 2017 |

| Nasibullah | 7 | Chinari, 10 February 2017 |

| Sultan Aziz | 7 | Mata Lakara, 9 February 2017 |

| Freshta | 8 | Shakar Sheela, 11 February 2017 |

| Najiba | 8 | Chinari, 10 February 2017 |

| Zia ul Haq | 8 | Shakar Sheela, 11 February 2017 |

| Rohulla | 9 | Shakar Sheela, 11 February 2017 |

| Rozi Gul | 10 | Mata Lakara, 9 February 2017 |

| Sultan Wali | 12 | Mata Lakara, 9 February 2017 |

Investigating the attacks

It is not clear what the target could have been in any of these strikes. The UN said nine Taliban fighters were killed when the house next door to Gul’s was hit, though Gul denies there were any Taliban combatants in his village.

Rahman, too, said that there were no Taliban in his village, insisting the closest were about 15 minutes walk away. But Hayatullah Hayat, the governor of Helmand, told the Bureau that the house next door to Fida Mohammad’s had been struck because the Taliban were using it as a base for attacks on the district centre. Sardar Mohammad, an Afghan policeman, also said there were Taliban nearby. According to Mohammad, the strike killed five Taliban fighters who were sheltering in Fida’s compound after incoming fire had hit their previous position.

Ghafar also said there was no Taliban near his house, just a nearby army checkpoint. But Sardar Agha Ibrahimkhel, an Afghan army captain, said that unbeknownst to Ghafar Taliban fighters had been trying to dig a tunnel under one of the checkpoints. Scores of Afghan soldiers in Sangin had been killed by the Taliban tunnelling under checkpoints, packing the shafts with explosives and then detonating the charges.

Ibrahimkhel said the US struck Ghafar’s house by accident as they tried to repel the Taliban advance. He said that the problem was that the US “see the people in the area but can’t tell whether they are civilians or others”.

Finding out who is responsible for causing civilian harm is important not just from the point of view of justice. It is vital for forces which want to avoid civilian harm to learn lessons from actions that cause it. Knowing how civilians came to be killed informs policies and rules of operations.

Afghanistan has been a textbook example of how policies at the top can affect the civilian death rate on the ground. In 2008, a quarter of all civilian deaths in Afghanistan were attributed to either Afghan government or Nato airstrikes. Six months after the UN report came out, General Stanley McChrystal, the Nato commander in Afghanistan, vowed to reverse the trend and banned the use of airstrikes on domestic homes in all but the most extreme circumstances for this express purpose. His successor the next year, General David Petraeus, elaborated on this. He told commanders they had to be certain there were no civilians present before allowing strikes to go ahead, except on two conditions that were redacted from the published version of his order.

Policies such as these slashed the civilian casualty rate. In 2009 a civilian died in every sixth strike, on average. In 2010 this was down to one dead in every fifteenth strike.

At some point the near-blanket ban on targeting domestic buildings seems to have been changed. After a series of high profile strikes with high civilian casualty counts, culminating in the bombardment of houses in the northern city of Kunduz that killed 33 civilians, a new rule was introduced requiring commanders to get permission from headquarters in Kabul before striking a building.

The Bureau’s Shadow Wars Dispatch

Subscribe to the Shadow Wars newsletter and hear when our next story breaks.

If there was decisive evidence the US did carry out the Sangin strikes, it could trigger further tightening of restrictions on targeting buildings. If it was ANSF mortars or rockets then its own civilian casualty mitigation team could use it to develop better policies and further reduce civilian casualties.

The problem is, it is harder to investigate civilian casualties allegations from airstrikes with only a small force and limited or zero access to the scene of strikes, a senior US military official told the Bureau.

The official's most recent work has focussed on Iraq and Syria, but his analysis also applies to Afghanistan, he said. “Not only do we not have access, as the military”, but that even aid agencies don't “have access they once had...so it’s much harder to really dig into an allegation.”

Now, “when I do my post strike analysis we may pick up signals intelligence that an ambulance got launched out to that particular location or that there’s a news report that there were civilian casualties that happened there.” US troops cannot go to the scene and see the impact and talk to people and "that is incredibly challenging to try and figure out what exactly happened,” the official added.

“The challenge now is the access and the lack of access. Before we had 150,000 troops there". He added that then it might not find out exactly what happened, the "ground truth". However, he added, you did at least get "another perspective or an allegation, whereas now we don’t have that luxury any more.”

In the case of Sangin, Resolute Support said it had “accounted for every munition down to precise latitude and longitude” and “could not find a link between our strikes and the alleged civilian casualties”. But it was short of an outright denial.

Helmand’s governor told the Bureau in July an Afghan government investigation was still going on. “I hope we will reach a conclusion that whether these were done by the RS [Resolute Support], or by the rockets of the enemies,” he said.

Today, Sangin remains under Taliban control. It is in the insurgents' heartland, according to the US military in Afghanistan. A local politician told the Bureau that both the Taliban and local Afghan forces operate in the district, but that fighting has become less intense since President Trump announced his new strategy towards the country, as if insurgents are waiting to see how their enemies will try and oust them from their prize.

In Sangin meanwhile, the Gul, Rahman and Ghafar families are picking up the pieces. Governor Hayat has given them each some money out of his provincial coffers. He told the Bureau he expects they will eventually get more compensation from the central government.

The Afghan intelligence service, Helmand police, council, and the governor all agreed that Hamid Gul's family were civilians and he should be compensated. The Bureau first spoke to him in February, but five months later in July he said he was still waiting on Kabul to decide his case.

Ghafar, similarly, has been left with nothing. He struggles to understand how this happened. His family was well known and trusted by the soldiers on the checkpoint. He used to live in a busy neighbourhood but his neighbours gradually left due to the conflict, till his family was left alone.

“My wife and I promised that we will not leave our house and we will not go to Pakistan or Iran...no-one, government or Taliban, had anything to do with me,” he told the Bureau. “If there were Taliban they should have hit them. Why did they hit us?”

He is now in debt and struggling. “I had a nice house and people wanted it for a lot of money but now I am looking after the injured,” he told the Bureau. “I am left with nothing. Not even one item was recovered.”

Additional reporting by our Afghan specialist

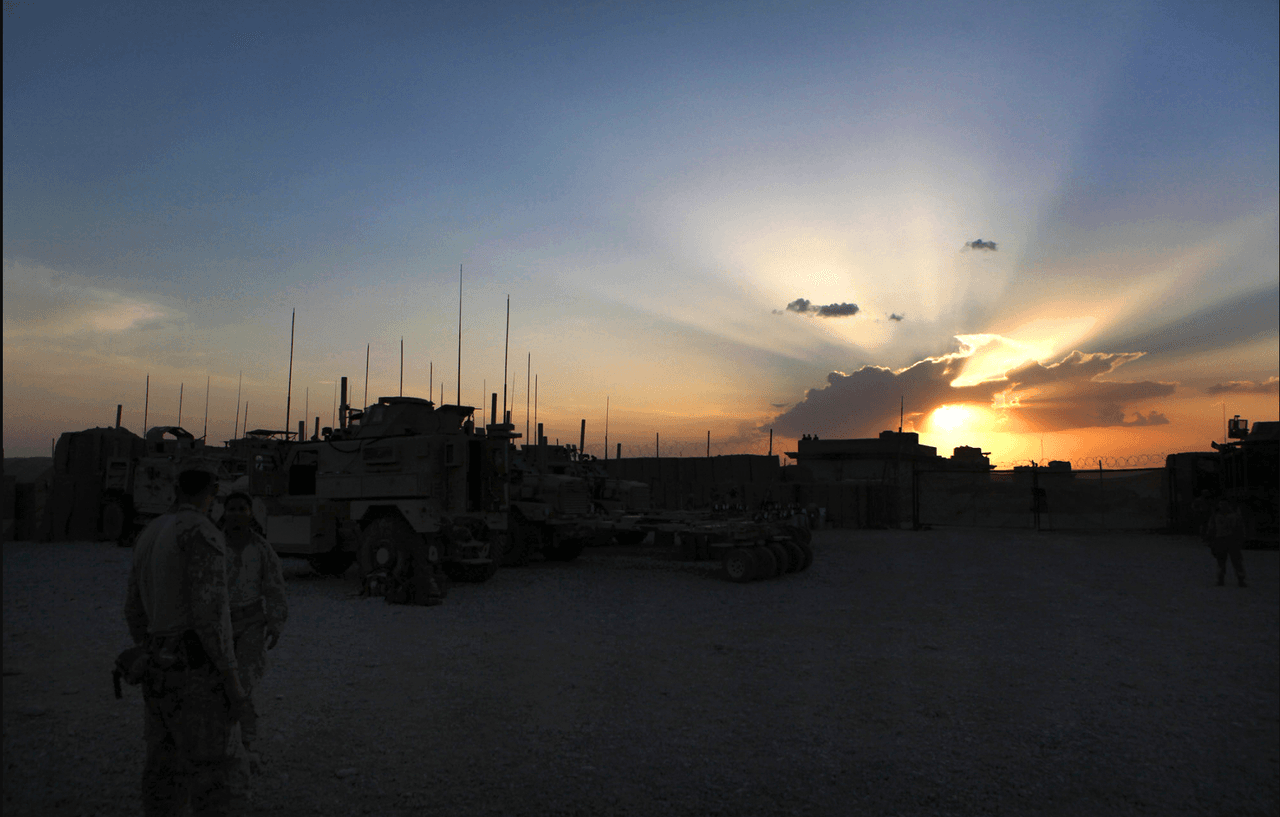

Main image, of the aftermath of an airstrike, via Captain Sardar Agha Ibrahimkhel