The "dark ads" election: How are political parties targeting you on Facebook?

The Facebook election battle is in full swing, the Bureau can reveal, with at least 68 different types of political adverts tailored to individual social media users being paid for by the three main parties in the last month.

The Bureau has been given access to the first dataset ever collected that shows how UK voters are being targeted with specific messages in an attempt to influence their vote.

The shadowy world of online political advertising has until now gone largely unmonitored, despite the huge power and reach of Facebook and despite social media messaging being thought to have contributed to the Donald Trump and the Vote Leave victories.

A new project called Who Targets Me is attempting to address this, by recruiting social media users to share information on what adverts they are seeing. The Bureau’s new data journalism team the Bureau Local will analyse the data collected in an attempt to shed light on an opaque and rapidly growing industry.

This is a “dark ads” British election, warned Will Moy, director of independent fact checking website Full Fact - a phenomenon which could have sinister consequences.

"It's possible to target dark ads at millions of people in this country without the rest of us knowing about it,” he said. “Inaccurate information could be spreading with no-one to scrutinise it. Democracy needs to be done in public.”

Help the Bureau Local investigate how targeted messaging is being used in the General Election

Sign up to Who Targets Me? hereDatabase aims to shed light on a secret world

There has been a huge rise in political advertising on social media in recent years, with the reams of personal information held by Facebook on each user’s demographics and interests revolutionising the way political parties and candidates can speak to voters.

Facebook can provide data on different users’ ethnicities and occupations and what issues they care about, allowing campaign teams to target specific voters with specific messages. That means that unlike billboards or newspaper ads which everyone sees, the world of targeted advertising is extremely hard to track.

In an effort to do something about this lack of transparency, Who Targets Me has built a browser extension for Facebook users to download that will then report live to that individual when a political advert is being targeted at them. It also tracks that information in its database.

More than 4,000 people across the UK have so far installed the extension, making the Who Targets Me dataset the largest of its kind, though it can still only provide a small snapshot of the overall picture. There are more than 30 million Facebook users in the UK, meaning the true figures for political advertising on the network is likely to be much higher than what our sample shows.

The Bureau Local is urging more people to sign up in order to further investigate the scale and detail of targeted advertising in the lead up to the election.

What we know so far

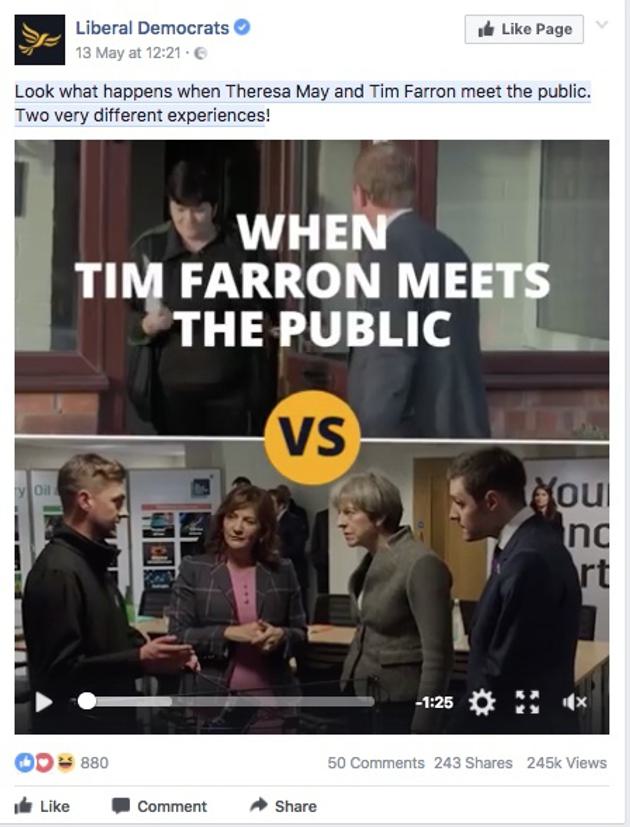

The data collected so far shows at least 68 different Facebook adverts have been paid for by the three main political parties. They have been seen by social media users in their newsfeeds or in advertising sidebars more than 1,400 times.

Of those ads, 34 came from the Liberal Democrats, 10 from Tim Farron’s official account, 10 Conservative and 14 from Labour.

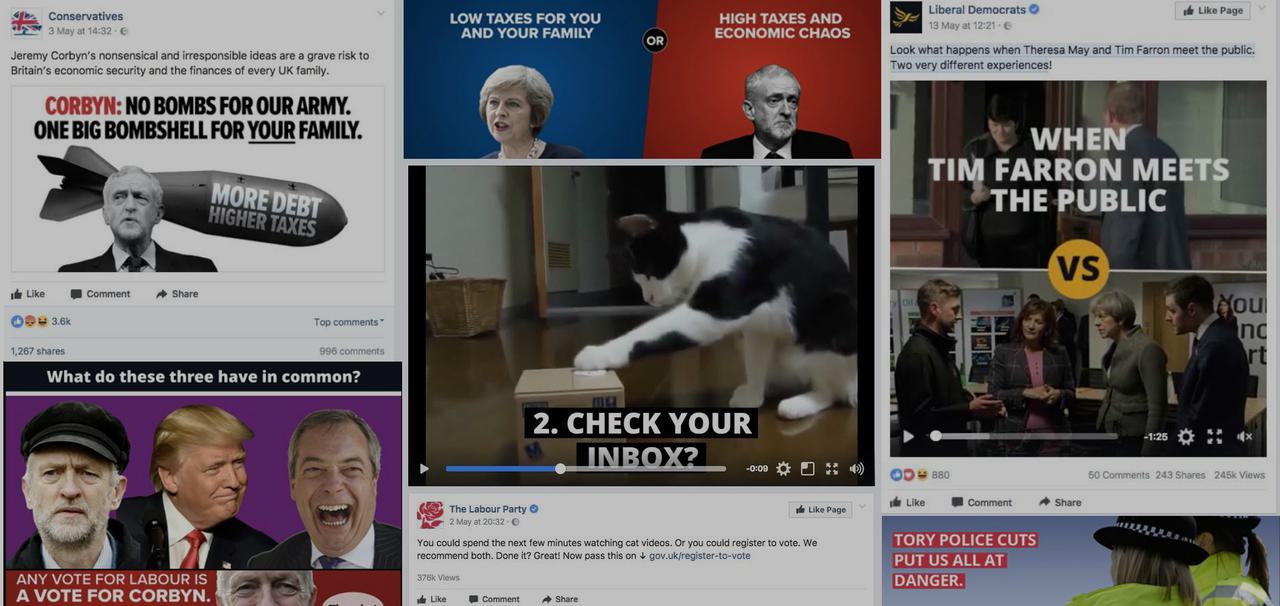

The Bureau found the Conservative party consistently attacking Jeremy Corbyn by name in each of the ten ads, with mention of Theresa May as a positive alternative in nine of them.

One ad reads: “A leader who supports our armed forces or one who wants to abolish them? The choice is clear: Corbyn and your security is too big a risk.”

By comparison, only two of the 14 Labour ads mention Theresa May.

Only one of Labour’s official ads uses an image or quote from Jeremy Corbyn. In another he is briefly mentioned in a filmed speech by actor Maxine Peake, but otherwise the adverts avoid any mention of the Labour leader, opting instead to focus on voter registration and issues such as taxation and foxhunting.

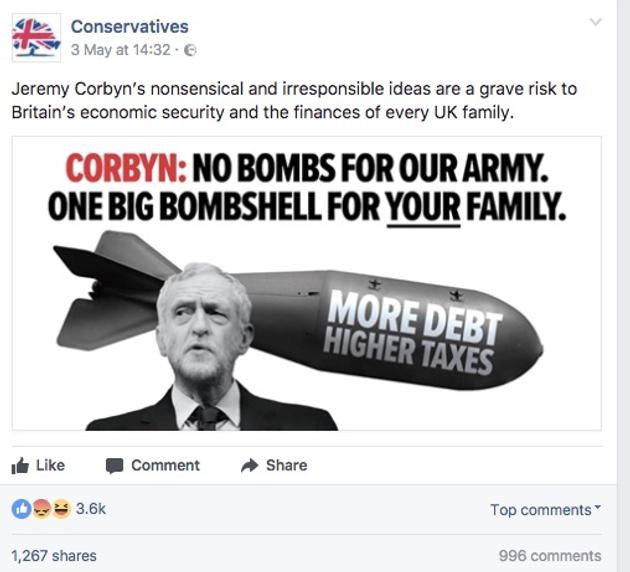

Of the 44 Liberal Democrat ads collected, 12 attack Corbyn by name and 15 attack May.

Our analysis also revealed Labour and the Lib Dems’ use of surveys and petitions in their adverts to pull in more email addresses of potential voters.

An ad from the Liberal Democrats, reads: “Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn are both trying to avoid taking part in TV debates - if you think they should, add your name today.”

Labour, by comparison, are apparently focusing on trying to get young people to sign up to vote. One video ad, logged by a 23-year-old in Oxford West And Abingdon, reads: “You could spend the next few minutes watching cat videos. Or you could register to vote. We recommend both. Done it? Great! Now pass this on” - with an arrow pointing to a voter registration link.

The power of targeted advertising

In the run-up to the 2015 General Election a combined £1.3m was spent on targeted Facebook advertising by political parties, accounting for about 23% of the total advertising budget, according to the Electoral Commission.

Social media gives parties a lot more for their money, with online ads costing far less than those published in newspapers and reaching a much wider audience, points out a recently-published research paper by the London School of Economics’ Media Policy Unit.

Yet despite the large and growing sums being spent, what politicians are saying in their online publicity remains in large part unmonitored. Only Facebook knows what users are being shown what adverts - and privacy obligations combined with commercial interests mean that information is not publicly accessible.

Dominic Cummimgs, campaign director for Vote Leave during the Brexit referendum, has claimed the group spent 98% of its £6.8m budget on digital advertising, publishing nearly a billion targeted digital adverts, mostly via Facebook.

In one day last August meanwhile, Donald Trump’s campaign showed ads to Facebook users that linked to 100,000 different web pages, each microtargeted at a specific group of voters, according to the campaign’s digital director Brad Parscale.

Following the last general election, Facebook claimed the Conservative Party had been able to serve ads to 80% of the site’s users in the key marginal seats. “The party’s videos were viewed 3.5 million times, while 86.9% of all ads served had social context — the all-important endorsement by a friend,” its business page boasts. “Facebook played a vital part in a highly targeted campaign, helping the Conservatives speak to the right people—over and over again.”

More volunteers are needed

While the sample group of adverts is still too small to make any meaningful conclusion so far on how different demographics are being targeted, the Who Targets Me set of social media advert data is the largest collected so far.

In the US, the New York Times attempted a similar project to collect data behind Facebook ad targeting during the US election but did not have as many volunteers taking part as those so far recruited in the UK.

Jeremy Merrill, a journalist from the New York Times who ran the newspaper’s project said: “I'm excited to see more and more attention paid to how political campaigns target ads to voters.

“It's now possible for a political campaign to send one message to one set of voters without another set of voters even knowing that message exists. While it's important to keep in mind that ad targeting isn't new, there's an opportunity for it to be much more granular on the web.”

To get a fuller picture of what the political parties are telling people online, Who Targets Me needs more people to sign up. It wants volunteers of all ages and genders from all political backgrounds and affiliations, in order to get the most representative sample possible.

Sign up to be a Who Targets Me volunteer here

Its current volunteers stretch across most of the UK (594 out of 650 constituencies) but in some cases there is just one person per constituency or none at all. The vast majority (81%) are men and the average age is 37 years old.

“We're in a new era for political campaigns - one where the message a party has for you can be personally tailored to your likes and preferences,” said Jeffers. “If we, as voters, don't take a moment to think about how campaigns are being run, we'll end up having more and more advanced techniques used on a narrower and narrower slice of the voting public.”

The Bureau Local will work with local journalists across the UK to help them gather data about online ads in the area and cross reference this with traditional published material.

We are a new journalism and technology team at the Bureau of Investigative Journalism which is building a network of collaborators to dig into different types of datasets and tell the stories that matter to local communities. If you want to become part of the Bureau Local network sign up here.