Superbugs killing twice as many people as government says

Superbugs are now killing more patients than breast cancer and at least twice as many people as the government estimate, experts have warned.

The Bureau has also established that the government’s stated figure of 5,000 people a year dying from superbugs is based on guesswork. And we have obtained official NHS data confirming that significantly more people than that died with drug-resistant infections last year.

The growth in infections that are resistant to antibiotics (also known as anti-microbial resistance, or AMR) is one of the biggest health crises facing the world today. Scientists have warned the world is on the cusp of a “post-antibiotic era” – where everyday infections will become untreatable and potentially fatal – unless concerted global action is taken. Yet the UK has no standardised system for recording the prevalence of AMR deaths, meaning the full scale of the problem here is unknown and it cannot be properly responded to.

NHS England’s chief medical officer, Professor Dame Sally Davies, has repeatedly claimed antibiotic resistance kills 5,000 people in the UK each year. Yet at least 12,000 people in the UK are likely dying each year just from drug-resistant sepsis (blood poisoning), according to Dr Ron Daniels, chief executive of the UK Sepsis Trust and CEO of the Global Sepsis Alliance.

Sepsis is a serious condition where an infection – such as a lung infection or a urinary tract infection – gets into the bloodstream and poisons it. In severe cases, people suffer organ failure and die within hours. Effective antibiotic treatment is crucial to prevent death and reduce the long-term physical damage suffered by survivors.

Nearly half of sepsis cases are caused by an E.Coli bacterial infection; and about a third of E.Coli bacteria types are resistant to antibiotics.

At least 44,000 people die from sepsis each year – meaning that there are likely at least 5,000 deaths each year linked to antibiotic-resistant E.Coli sepsis alone, Dr Daniels warned.

Once all the cases of sepsis caused by other bacteria are taken into account, and the proportion of those bacteria which are resistant to antibiotics is factored in, the likely death count rises to a number more than twice as high as the official government estimate for all types of infections.

“We reach more than 5,000 deaths just with resistant E.coli alone. If we add in the other resistant bugs we get to almost 12,000 deaths,” said Daniels. “[And] sepsis is just one condition affected by antibiotic resistance, albeit the one that is likely to cause the most mortality.”

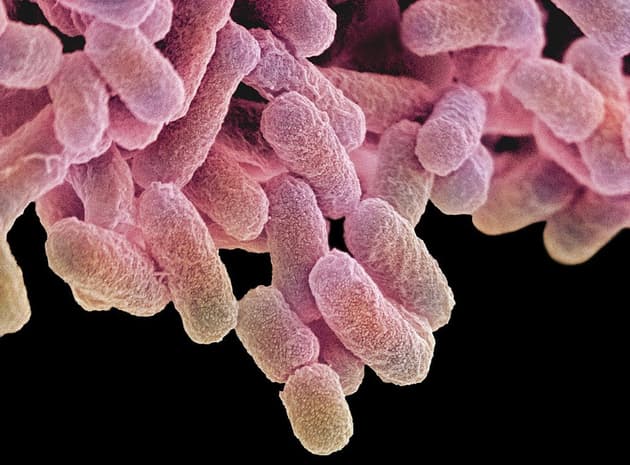

At least 5,000 people every year die from infections caused by E Coli bacteria (pictured) that are resistant to antibiotics, according to Dr Ron Daniels, chief executive of the UK Sepsis Trust. Photo from Getty Images

At least 5,000 people every year die from infections caused by E Coli bacteria (pictured) that are resistant to antibiotics, according to Dr Ron Daniels, chief executive of the UK Sepsis Trust. Photo from Getty Images

New data on deaths in hospitals also indicates that the government’s 5,000 figure is a serious underestimate. At least 6,060 people who died in English hospitals last year were carrying or infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria, according to records obtained by the Bureau from NHS Digital – the health service’s data collection arm.

This figure does not include deaths in Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland, and it only refers to deaths that happened in hospitals. It refers to all cases where a patient was recorded as having a drug-resistant infection, even when that infection was not the cause of their death – for instance someone dying of a heart attack who was screened upon entering hospital and found to be carrying MRSA.

However it is an undervaluation for a number of reasons. Antibiotic resistance is not always screened for or detected – and when it is, it is not always recorded in patient notes or on death certificates. Adding to the problem is the fact that the translation of those notes into NHS Digital data happens at an individual hospital level, and how well that translation is carried out varies between different hospitals. The various stages involved in diagnosis and recording means many cases of drug resistance never make it into the final tally.

The complexities of AMR

The distinction between antibiotic resistance causing deaths and contributing to deaths is important. Antibiotic resistance doesn’t kill people in and of itself; it just means an infection becomes harder, or impossible, to treat. The number of different factors affecting how ill someone gets from a particular infection and how they respond to different treatments means that even when the presence of an antibiotic-resistant infection is confirmed in a patient, and that patient dies, it is usually impossible to say whether or not they died as a result of that resistance. However it is known that AMR causes mortality rates for infections to rise – for instance, people are twice as likely to die from drug-resistant E.Coli than E.Coli that responds to antibiotics.

Superbug deaths estimate was based on flawed statistics

So where did the government get its 5,000 figure from? Quite simply, it made it up.

It took estimated figures on AMR deaths in the US and Europe, extrapolated those figures to the British population, then rounded the final numbers up. But the data it used was flawed, the extrapolation it did was rudimentary, and the rounding up was arbitrary.

The first study the government used was a 2013 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the US, which estimated at least 23,000 people die from drug-resistant infections there each year. The UK has a population size about 20% of the US, so the Department of Health took 20% of the US death toll figure to make an estimate for the UK of 4,600 deaths – then rounded that up to 5,000.

However it has already been revealed that the CDC figure was itself essentially guesswork and a serious underestimate. To come up with the 23,000 figure, the CDC mostly used a survey on AMR-related deaths in just 11 US states in 2011, and extrapolated those results to the US population. The CDC admitted the “limitations” of such a model, with the agency’s senior adviser for antibiotic resistance coordination and strategy telling Reuters that it had come up with a figure that was “an impressionist painting rather than something that is much more technical,” following pressure from Congress to provide a number.

“This was a ballpark figure based on a single study,” Dr Ramanan Laxminarayan, director of the US’s Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy, told the Bureau. “These were not scientific estimates but rather [numbers to be] used for advocacy. I think 23,000 is a gross underestimate, it is probably twice that number.”

There is no standardized way of recording deaths from superbugs, and so it is impossible to know the true extent of the problem. Photo from Getty Images

There is no standardized way of recording deaths from superbugs, and so it is impossible to know the true extent of the problem. Photo from Getty Images

When explaining to the Bureau how it came up with its 5,000 figure, the DoH also referred to a study by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. That report, published in 2009, estimated there were 25,000 deaths directly caused by multi-drug resistant bugs in Europe each year.

It came up with that figure by looking at the prevalence of five different multi-drug-resistant bacteria in EU member states, plus Iceland and Norway. It estimated how many infections would be caused by that bacteria, then applied the known mortality rate for those infections (which in each case is higher than the mortality rate for infections caused by bacteria which are susceptible to antibiotics). Like the CDC, the ECDC also stressed in its final report there were many reasons to believe its figure of 25,000 was an underestimate.

The DoH told the Bureau it extrapolated that 25,000 figure to the UK population, which resulted in a figure of 2,500 deaths here – it did not explain how that extrapolation was calculated. It said it then doubled the number to 5,000 because the ECDC report was published nine years ago and only looked at five bugs.

The ECDC report also only estimated the number of deaths directly caused by drug resistant infections, whereas the DoH wanted an estimated figure for all deaths in which drug resistance played a role.

Death certificates often don’t include superbugs

The real number of people dying from or with antibiotic-resistant infections across the UK is almost certainly far greater than 5,000, but with no standardized recording of deaths it is impossible to know what it is.

Even when a superbug has been diagnosed and the patient in question dies, the infection is often not recorded on the death certificate. Doctors have been urged to make sure infections from drug-resistant bugs MRSA and C. Difficile are recorded on death certificates, and they are supposed to put other resistant bugs on them too if they contributed to the deaths. But there is no standard procedure and no checks on whether existing death certificate advice is followed.

There are many reasons why these infections don’t make it onto death certificates. It is often too difficult to say if the drug resistance directly caused or contributed to the death. The cause of death might have been decided and recorded before laboratory results came back showing the patient’s infection was drug-resistant. Outside of critical care units it is usually junior doctors – who are less experienced at pronouncing causes of death – that fill out the forms. And what killed the patient is subjective; it is just one person’s opinion.

On top of this, hospitals can be reluctant to record drug-resistant infections for fear it will reflect badly on them, given that superbugs have in the past been associated with poor clinical hygiene. “It is like saying they are at fault and they don’t want to be claiming that, so the magnitude of the problem is under-reported,” said Dr Laxminarayan.

The importance of an accurate death count

Accurate death counts are crucial because they provide a clear measure of how serious a public health problem is, Dr Laxminarayan stressed.

Without knowing the true extent of antibiotic resistance hospitals will not take all the action necessary to stop resistance growing and superbugs spreading. “In the NHS it is very difficult to obtain funding to try to prevent a problem that is not yet seen as a problem,” said Dr Mike Cooper, a consultant microbiologist and director of infection prevention and control at Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust.

“The experience at many hospitals is that the necessary investment in infection prevention and control is only made after the multi-drug resistant bugs are already out of control, rather than at the point when interventions could have prevented or slowed this process.”

Failure to pay attention to AMR is the prime reason it has turned into a global crisis, Dr Laxminarayan pointed out. “Not recording public health problems means they get out of control,” he said. “That’s happened for antibiotic resistance. For many years it was undercounted and nobody did anything about it. We can’t let that continue to happen.”

Ignoring resistance has already caused serious amounts of suffering and loss of life. Sepsis caused by drug-resistant infections is killing more than 56,000 newborns in India and nearly 26,000 in Pakistan each year. Global travel and medical tourism means superbugs bred in one continent quickly travel all over the world

Follow the Bureau's antibiotic resistance updates on Twitter: @TBIJAntibiotics

British government raises profile of superbugs

The British government has been successful in raising the profile of antibiotic resistance on the global agenda. After six years of campaigning, Professor Dame Sally Davies secured a United Nations general assembly meeting in September, where all 193 countries signed a declaration to tackle the problem of superbugs.

Yet the local surveillance system for resistant infections in the UK is far from perfect, doctors warn. Hospitals in England are required to send details of bloodstream infections from MRSA, its non-resistant cousin MSSA and E.Coli to Public Health England (PHE), as well as cases of C.Difficile infections. PHE has published one report on deaths from these, and has indicated it eventually wants to expand the surveillance system so it is linked to mortality data.

Dr Cooper acknowledged the system is “streets ahead of everywhere else in the world” but said the government ought to be routinely counting deaths. “Take ESBL [multi-drug-resistant] E.coli. I keep fairly good records of blood cultures, but I don’t have clear records of outcomes,” he told the Bureau. “Public Health England has no idea because it has no outcome data. This is a serious mistake. It can draw nice graphs but it has nothing to show these infections are managed.”

The Department of Health described its estimate of 5,000 deaths a year from superbugs as “plausible”. A spokesperson said the government had spent hundreds of millions of pounds fighting the threat of drug-resistant infections and had persuaded doctors to prescribe fewer antibiotics, as well as leading the global initiative to make fighting superbugs a priority.

Public Health England told the Bureau it had made “huge strides” in recent years in improving surveillance of anti-microbial resistance and passing this information on to health professionals.

The UK Sepsis Trust is calling for a national register in which every case of sepsis is recorded, with details of the bacteria which caused it and whether that bacteria was resistant to antibiotics. It would include information on whether the patient died and if not, what impact the condition had on their quality of life years later.

The majority of people who die from a bacterial infection die from sepsis. So if this proposed register existed, it would record the bulk of AMR-related deaths. The UK Sepsis Trust also wants to see the information from this register mapped to antibiotic usage around the country, to see whether there are any regional correlations between prescription practices and levels of resistance to different drugs.

“We know globally we see 18 million cases of sepsis [a year],” said Dr Daniels. “If we don’t have antibiotics that work those 18 million people will die. In the UK the 150,000 people a year who get sepsis will die. Conserving antibiotics to treat sepsis is absolutely, literally, vital.”