A list of the 28 detainees held by CIA’s detention program in 2006 – its ‘final’ year

More than four years after President George W Bush responded to the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York, a total of 28 detainees began the New Year of 2006 in the CIA’s secret prison programme.

This was the same year the programme was later disbanded.

One man in the CIA’s possession was Janat Gul, who had in July 2004 been transferred to one of the agency’s secret prisons from a foreign government. CIA officers initially thought he was a senior al Qaeda fixer, but some time later, they began to realise he was simply a “lazy” and poorly educated village man who had been looking for easy money by doing errands for suspected terrorists.

However, this realisation came after a series of interrogations that left Gul suffering “’frightful’ hallucinations” and at one point he even “asked to die, or just to be killed”, according to a CIA cable highlighted in a report by the US Senate Intelligence Committee last month.

That summary report, which summarises five years of investigations by the committee, contains gruesome details of his torture at site “Black”, now identified as having been in Romania.

The detention facility’s chief noted that “there simply is no ‘smoking gun’ that we can refer to that would justify our continued holding of [Janat Gul] at a site such as” this.

Members of the US Senate Committee on Intelligence were so taken by his experiences, they quoted from CIA papers in last month’s report.

“[Janat Gul] was never the person we thought he was,” they quoted the CIA as saying. “He is not the senior Al-Qa’ida facilitator that he has been labeled. He’s a rather poorly educated village man with a very simple outlook on life. He’s also quite lazy and it’s the combination of his background and lack of initiative that got him in trouble. He was looking to make some easy money for little work and he was easily persuaded to move people and run errands for folks on our target list.”

The report noted that Gul was transferred to a foreign government and later released.

New research by the Bureau and The Rendition Project, which has established for the first time entry and exit dates for all 119 detainees put through the CIA’s controversial programme, reveals that Gul was one of 28 held by the CIA in its last year of existence.

Related story: Only 29 detainees from secret CIA torture program remain in Guantánamo Bay

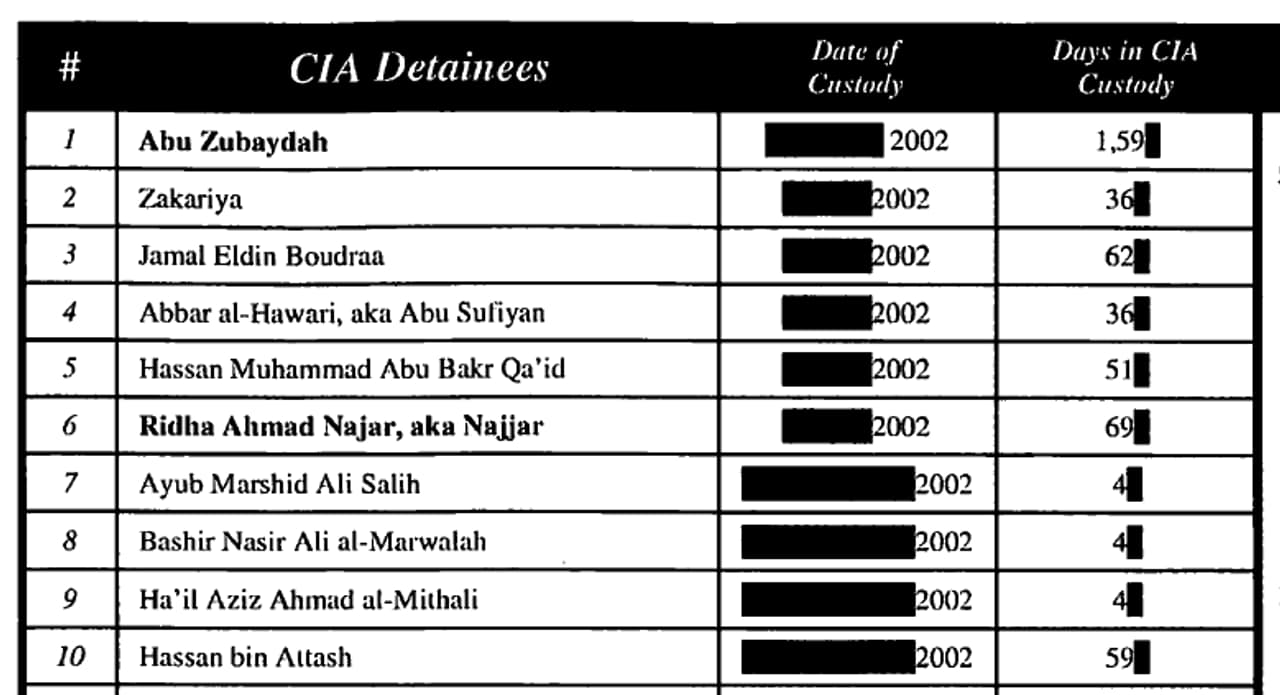

The full list of the 28 held by the CIA in 2006 is:

Ibn Shaykh al-Libi

Abu Yasir al-Jaza’iri

Majid Khan

Mohd Farik bin Amin, aka Abu Zubair

Riduan bin Isomuddin, aka Hambali

Hassan Ghul

Saud Memon

Hassan Ahmed Guleed

Abu ‘Abdallah

Abd al-Bari al-Filistini

Marwan al-Jabbur

Qattal al-Uzbeki

Ahmed Khalfan Ghailani

Abdi Rashid Samatar

Abu Faraj al-Libi

Abu Munthir al-Magrebi

Ibrahim Jan

Abu Ja’far al-Iraqi

On September 6 2006, President Bush announced that 14 prisoners had been moved from the CIA’s custody to the military camp in Guantánamo Bay. This statement was the first formal acknowledgement by the US government that the CIA had run its own separate detention system.

At this point, the CIA’s secret prisons were officially empty, and would remain so with two exceptions: Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi, rendered to the CIA in November 2006, and Muhammad Rahim, a “new guest” of the programme who arrived at site “Brown” in Afghanistan in July 2007.

Among those held in 2006 and not destined for Guantánamo, Firas el-Yemeni (otherwise known as Khaled el-Maqtari) was transferred to Yemen in late August 2006. Two prisoners – Marwan al-Jabbur and Abd al-Bari al-Filistini – were moved to Jordan. They had been captured together and moved into the CIA programme on June 16 2004.

After his release Jabbur told Human Rights Watch he was aware that another prisoner was with him on his transfer out of Afghanistan, but he did not know who it was.

The Senate summary report notes that Abu Ja’far al-Iraqi was transferred from CIA custody in Afghanistan back to the US military in Iraq in early September 2006.

Two prisoners held by the CIA during this period were released and later died in Pakistan: one, Hassan Ghul, was reportedly killed by a drone, while Saud Memon – captured in the first quarter of 2004 – reappeared in April 2007. According to an article in the Wall Street Journal, he was badly injured and had “lost all his senses”. He died soon afterwards.

Another former CIA detainee to die in mysterious circumstances was Ibn Shaykh al-Libi. The latter part of Ibn Shaykh’s detention by the CIA – which lasted from February 9 2003, after they had him transferred from proxy custody in Egypt where he had been tortured – has never been documented.

The Bureau analysis of the summary report reveals that he was transferred out of the programme between March 25 and April 3 2006. This corresponds to the closure of the “Violet” site in Lithuania on March 25. Prisoners were taken to Cairo and then to Afghanistan. Ibn Shaykh, however, was eventually relocated to Libya, where he was found dead in prison in May 2009.

The fate of several others among these 28 prisoners remains completely unknown.

Abu Yasir al-Jaza’iri was transferred from the programme in late July or August 2006, around the same time that other “high-value detainees” were taken to Guantánamo. He did not end up there, however. Also moved out around the same time were Abu ‘Abdallah, Qattal al-Uzbeki, Abdi Rashid Samatar, Abu Munthir al-Magrebi and Ibrahim Jan.

Note on Methodology:

The Senate committee’s report lists 119 detainees who were put through the CIA’s detention and interrogation programme.

Many of these individuals were not previously known. The Bureau’s new investigation in collaboration with The Rendition Project has produced a database which begins to provide details of what happened to each of these 119 individuals.

The database is available here. [Note: At the time of publication, we made the data freely available. However as our investigation has progressed that data is now out of date. For the latest data please see our first quarterly report.]

The investigation has began by attaching entry and exit dates to the 119 detainees that went through the programme. The starting point for this analysis is that the chart at the end of the report is chronological. This implies that each prisoner entered the programme on the same day or after the previous prisoner, and on the same day or before the next prisoner on the list.

Although the report itself gives few exact dates on which particular prisoners entered the programme, it gives numerous quite precise indicators. These include references to when “enhanced techniques” were first practised on specific individuals. Such references determine a date by which that prisoner had entered the programme.

A note on dates: although many months are provided, the actual days in the month are often redacted. In such cases, the size of the black redaction mark provides an indication of whether it is a single-digit or double-digit date.

Previous investigations – by legal teams, journalists and organisations such as Reprieve, The Rendition Project, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and Open Society Justice Initiative – have given well-documented dates of transfers into, or out of, the programme in specific cases. In some instances these dates have been correlated with flight data from planes associated with the rendition programme.

In cases where testimony from released prisoners and known flight data intersects, we have used these dates as firm entry or exit points for those prisoners. In cases where exit dates have been attested by a combination of such sources, we have worked backwards to estimate a range of entry dates.

For the minority of prisoners who were sent to Guantánamo Bay, a date of transfer into military custody on the base is generally included in the documents hosted on the New York Times’s Guantanamo docket. This transfer date can be a useful indicator of exit date from CIA custody, but is rarely equivalent, since the majority of former CIA prisoners spent a period in military custody in Bagram before their final transfer to Guantánamo. Occasionally this transfer date is also documented, but more frequently it is only vaguely recorded (eg “May 2004”) or not recorded at all. The relative lack of transparency surrounding Bagram means that records of entry and exits there are harder to come by.

In some cases, the Guantánamo docket or public source reporting offers firm capture dates for prisoners, but since many were captured by foreign governments or held outside the CIA programme for an initial period, a capture date rarely equates to a date of entry into the CIA programme. When prisoners were held by foreign governments before or after their entry into the CIA programme, these periods are generally not included in the figures given in the chart.

We have flagged the 36 prisoners who we know were subsequently sent to Guantánamo. Their names often occur with significant variation on the Guantánamo docket, however. There may be additional detainees who went through the detention and interrogation programme who were moved to Guantánamo. We will update our research if we find this is the case.

The Bureau’s reconstruction of entry and exit dates has erred on the side of caution, giving date ranges unless reliable and documented sources for precise dates have been published. In some instances, we have flagged potentially inconsistent dates, and we will investigate these further. We have also noted where the range of possible exit dates extends beyond September 6 2006 – a date on which the programme was officially holding no prisoners – and we assume that these prisoners had left the programme by this date.

We anticipate that as more material is developed and surveyed, the ranges on this spreadsheet will become narrower. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the figures, we will continue to monitor them and correct them where necessary.

This report is part of a joint investigation between the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and The Rendition Project and is being supported by the Freedom of the Press Foundation.

*To support the Freedom of the Press Foundation’s fundraising appeal for this investigation, click here.