Why self-exclusion is not an answer to problem gambling

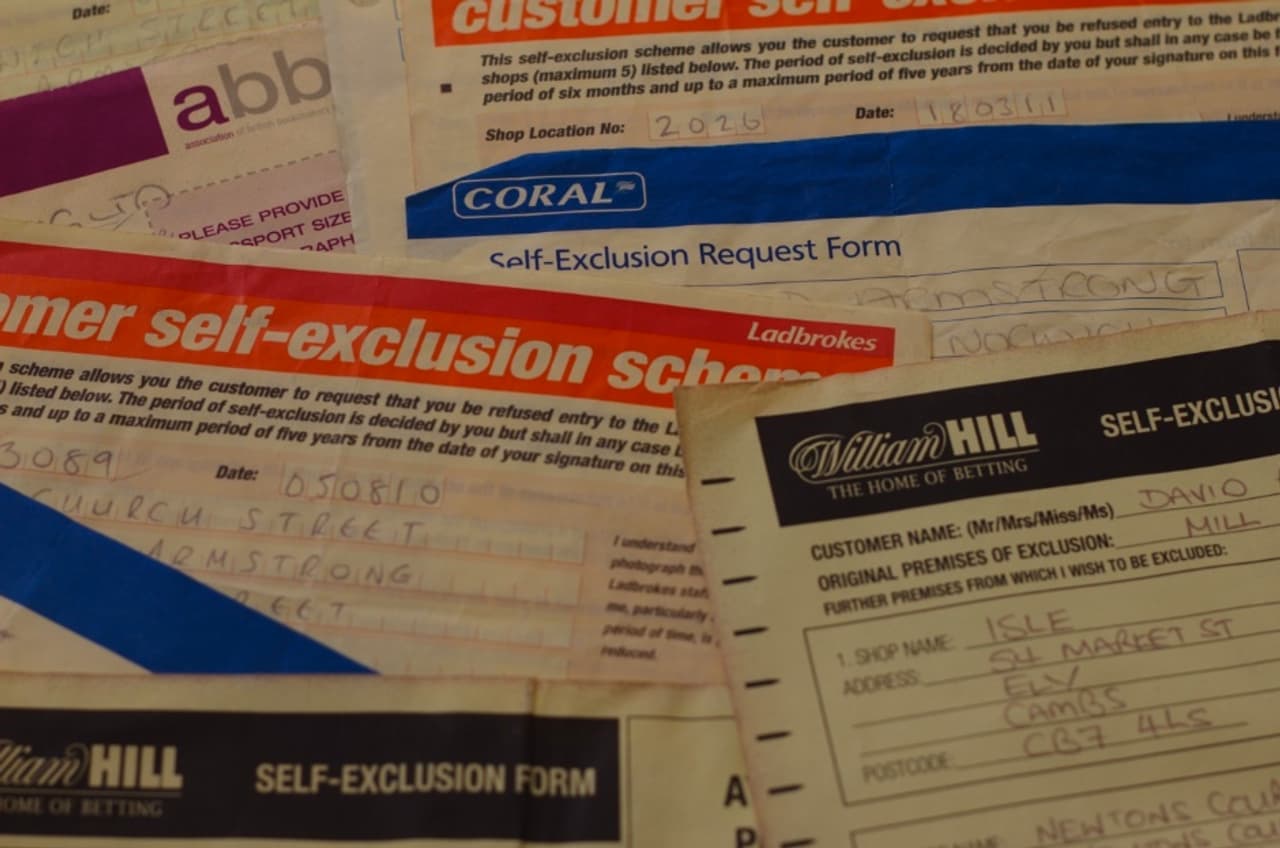

Signed, sealed, and undeliverable: self-exclusions.

One of the key measures to help problem gamblers manage their addiction is self-exclusion – but even bookmakers admit the system is flawed and hard to police, while critics claim betting shop staff may be discouraged from enforcing them.

Self-exclusion is a formal agreement with a bookmaker that it will no longer accept your bets for an agreed time, up to a maximum of five years. The process is fiddly and time-consuming. Anybody seeking help must take a form and passport photo to individual branches they feel they may try to bet in, although they can often nominate other branches on the form.

Gambling Commission figures show the number of self-exclusions has risen by 45% in just two years, from roughly 11,500 in 2008-09 to 20,823 in 2010-11 – although as one individual often fills out multiple self-exclusion forms, this doesn’t indicate how many individuals are affected.

But gambling addicts have found self-exclusions are often ineffectual at helping them manage their problem. When their own self-control lapses, many problem gamblers have found they have been allowed to bet again unchallenged in betting shops from which they have excluded themselves. The Gambling Commission records 10,468 ‘known breaches’ of self-exclusion in 2009-10 – more than double the reported breaches of just a year before.

And even when gamblers successfully exclude themselves from their regular haunts, the sheer number of betting shops in many areas means that fresh temptation is often just around the corner.

As counselling, therapy and hypnotherapy failed to curb problem gambler David Armstrong’s urge to bet huge amounts on fixed-odds betting terminals, he turned to self-exclusions. He banned himself from every betting shop in Norwich, and even further afield – but found that he was often able to bet again in the same shop.

Community spokesman

‘They’re impossible to police, these self-exclusions – the forms just get put in a cupboard and left to gather dust,’ said David Armstrong, producing a sheaf of official-looking yellow forms.

He has repeatedly been able to bet in shops he has banned himself from – most recently losing £650 in a single afternoon in a branch of Coral, despite having self-excluded himself from it. Other problem gamblers say they have encountered similar problems.

Related story: How Britain got addicted to bookies’ betting terminals

A Coral spokesman said: ‘Self-exclusion does still mean there is an onus on the customer not to enter our shops and this is made very clear to them. When a customer chooses to self-exclude we provide them with a form where they highlight a primary shop and they also have a choice of three further secondary shops to be excluded from, as self-exclusion is always most effective at a customer’s regular shop or those in the locality of where they live and are known to staff.

‘We do everything we can to ensure the shop teams are aware of the customer, sadly in practice it is impossible to guarantee that the customer will not access a shop at some point if they are inclined to do so,’ the spokesman added.

‘There’s no joined-up working or thinking around self exclusion: there’s nothing to stop a customer from excluding himself from one shop and simply going down the road – and of course problem gamblers are often very high turnover clients,’ said a spokesman for Community, the trade union for betting shop workers. ‘The way betting shops are set up puts employees under pressure not to do it and we can understand where the pressure comes from.’

Legally unenforceable

The Gambling Commission produces a code of practice for operators of gambling machines such as fixed-odds betting terminals. This notes that complying with self-exclusions is not a condition of keeping a machine permit. And the courts have ruled that bookmakers are under no legal obligation to honour self-exclusions.

In 2008, a greyhound trainer called Graham Calvert sued William Hill after he lost £2m through his telephone betting account even after he had completed self-exclusion with the company. He lost: the judge – and then a Court of Appeal – ruled that although William Hill had failed in its duty of care, he was likely to have gambled the money away with another operator in any case.

If bookmakers can overlook self-exclusions in a process where the punter is clearly identifiable – as in the Calvert case – then they stand even less chance of being successful on the high street, where they rely on staff recognising individual gamblers. And on fixed-odds betting terminals it’s easy to lose significant amounts of money without going anywhere near the counter.

In its report on the consequences of the Gambling Act, the culture, media and sport select committee called on the government to create a new form of self-exclusion that is universally applicable across all gambling locations in the UK. But such a measure would be even harder for bookmakers to enforce, and would again rely on the gambler’s self-control.

A spokesman for GamCare, the treatment organisation for problem gamblers, said: ‘GamCare takes the view that self exclusion, whether from land based gambling operations or from online gambling, is one useful step which people who feel that their gambling is getting out of their control can take to keep themselves out of harm… But we recognise the system has its limitations.’

The spokesman added that there was ‘a risk of over-reliance on self-exclusion’ as a means of managing problem gambling.