Inequity in international public health spending

Karani Ziro shuffles awkwardly around his small plot of farmland on the banks of the Galana River, Kenya. The stooped, slender man cannot move like he used to. However it is not age that has caught up with Ziro but lymphatic filariasis, a disease which causes painful elephantiasis swellings in the limbs and groin.

‘The problem with this disease is the weight I have to carry,’ Ziro told a United Nations film crew, adjusting the loose material wrapped around his severely swollen groin. ‘My swellings weigh about three kilos. Wherever I go it feels like I am carrying luggage.’

It is burden Ziro must carry alone. His disease is one of a group of 13 Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) which, despite decimating the lives of over 1.4 billion people, are repeatedly over looked by international aid policy makers.

Inequality in spending

‘There is a serious inequity in spending on public health,’ said Dr David Molyneux, Emeritus Professor at Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

‘If you look at HIV spending in Sub-Saharan Africa you’ll see that in many countries it is more than the total public health spend. Meanwhile NTDs which affect billions and can be treated cheaply and efficiency are being ignored,’ he added.

NTDs together kill more people than maternal mortality and have a higher disease burden than malaria or TB and nearing that of HIV/AIDS. However, despite the severity of the situation, funding for NTDs is just a fraction of that spent on other diseases.

In many countries [HIV spending] is more than the total public health spend. Meanwhile NTDs which affect billions and can be treated cheaply and efficiency are being ignored.

Dr David Molyneux, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine

Figures from 2008-2009 showed the group of 13 parasitic and bacterial infections received 5.4% of DFID’s research and development budget, compared with 8.7% for malaria and 46.1% for HIV/AIDS.

Jeremy Lefroy MP is chairman of the All Party Group on Malaria and Neglected Tropical Diseases. He is keen to see NTDs recognised.

‘These diseases are neglected because they are not the things that hit the headlines,’ he said. ‘They tend to be debilitating diseases rather than immediate killers, so people look at the things that are causing the deaths and think we have to tackle these, but they do not look at the potential impact on the economy from a long term debilitating disease.’

Lymphatic filariasis, which plagues Ziro, is a prime example of how NTDs can have a devastating effect on the lives of suffers.

The parasitic disease is transmitted by mosquitoes and attacks the human lymph node system potentially causing elephantiasis, a painful and disfiguring swelling of the limbs and groin. Reduced mobility and stigmatisation means many people with the disease are unable to work and have to rely on others for economic support.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that over 120 million people are affected by lymphatic filariasis. One third of them lives with the painful, disfiguring symptoms of elephantiasis.

Financial sense

The economic effects of preventing and treating the disease are compelling.

Researcher Brian Chu found that in the first eight years of the WHO campaign on lymphatic filariasis there was an estimated £13.3bn of direct economic benefits to be gained over the lifetime of the 31.4 million individuals treated.

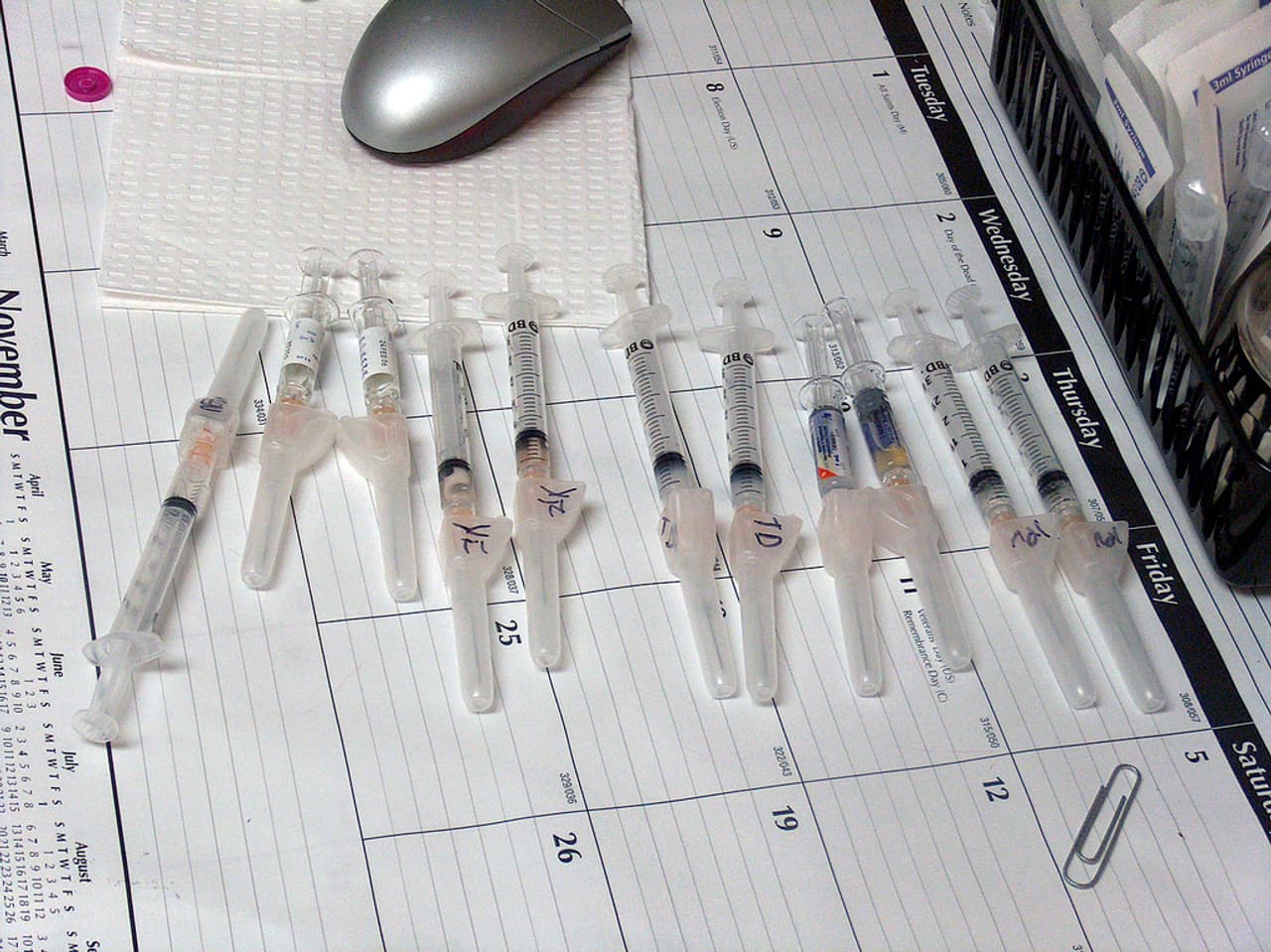

Treatments are cheap. One of principle means of addressing NTDs are mass drug administrations.

Lymphatic filariasis, for example, can be treated with a course of two drugs: albendazole and diethylcarbamazine (DEC). GlaksoSmithKline has committed to donating albendazole to all countries at risk for as long as necessary to eliminate the disease as a public health problem . DEC costs just 0.5p a tablet. But, despite the cheap cost of drugs, funding is still needed for logistics and distribution.

These diseases are neglected because they are not the things that hit the headlines. They tend to be debilitating diseases rather than immediate killers.

Jeremy Lefroy MP

‘It is absolutely in our national interests to fund programmes on NTDs,’ said Lefroy.

‘If we don’t we will certainly be facing consequences in the future, whether from increased immigration with people looking for a better life else because they simply cannot find it at home, or from food insecurity because people affected by debilitating diseases are simply unable to produce the food they need to survive.’

Molyneux too is convinced we need to rethink global health spending. ‘Treating NTDs is the best buy in public health. If we want to spend our aid money wisely then there is no better option than NTDs, we know our treatments work and they are cheap and they save lives. It’s a no brainer.”

After 11 years of suffering with the humiliation and pain of his disfigurement Ziro has finally heard of a free, medical clinic that had been set up in a neighbouring town. As the doctor tells Ziro that he can be treated a huge smile breaks across his tired face. It will take three operations and a course of drugs but for one man at least the neglect is over.