Ten years investigating US covert warfare

It’s a momentous week for the Bureau as we bring to an end our longest-running investigative project, on which we built our reputation. Our Drone Warfare team, which later evolved to become our Shadow Wars team, has spent 10 years investigating the global war on terror and documenting its devastating human cost.

All our projects have to come to an end at some point, and we feel now is the right time to move on from this one: US covert warfare is no longer the underreported area that it was when we began, it is increasingly difficult to pursue this kind of reporting, and we believe our drone data work is now better placed with Airwars – an organisation monitoring civilian casualties – than with our investigative journalism team.

As we say goodbye to this project, we want to pay tribute to the talented and dedicated reporters that worked on it over the years, and the powerful impact that their work achieved. Here’s a look back of 10 years investigating the shadowy activities of the world’s most powerful military and security forces.

Transparency

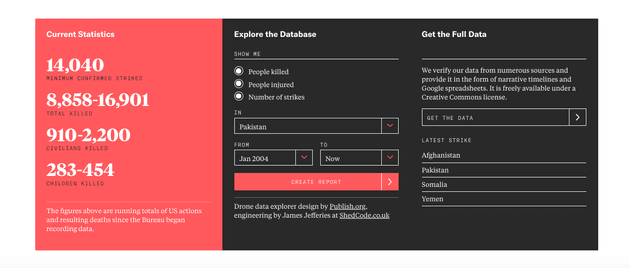

Chris Woods began this work at the Bureau in 2010, following the US drones hunting al Qaeda and its allies around the world. At that time there was a complete lack of official data on when and where airstrikes were being carried out and who was being killed in them. It soon became clear we would have to build our own datasets of strikes and casualties from scratch.

In 2011, we released our Pakistan database, compiled from thousands of news reports, NGO reports, government documents, and interviews with sources on the ground. Our Yemen and Somalia datasets came the following year, and in 2015 we started tracking US air and drone attacks in Afghanistan.

We became the go-to place for information. Our online datasets have been visited hundreds of thousands of times over the years, and used by all sorts of people and organisations in all sorts of ways. Amnesty International, the American Civil Liberties Union and Human Rights Watch are among those who have investigated or filed lawsuits off the back of our research; UN special rapporteurs and congresspeople have asked questions of made statements; academics, researchers, bloggers and others have used our information in their research or to make their own reports and visualisations. We have been cited tens of thousands of times in publications across the globe.

Our continued publication of this information ultimately contributed to a change in policy by the US. In June 2016 came a long-awaited announcement that figures on people killed in strikes would finally start being published – a move towards transparency which US government insiders said was a direct response to continued pressure from the Bureau and other organisations that used our data.

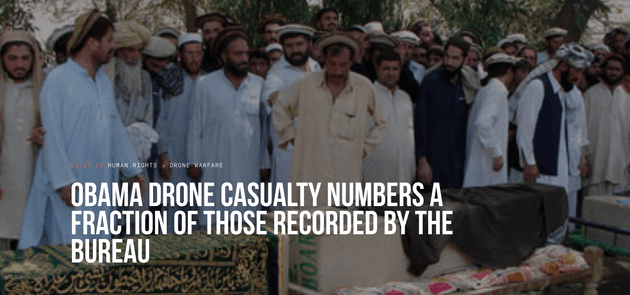

However the White House's number of civilians killed that year by US drone strikes – between 64 and 116 – contrasted strongly with the Bureau’s estimate, which was six times higher. We published a story with our version of the figures, data which was used widely by international media reporting on the announcement.

In 2017 the US then reversed their decision and stopped publishing any details on strikes at all, citing operational security. We continued publishing our data and our reporter Jess Purkiss was in regular contact with US government officials about the issue of transparency. In 2018 the blackout was again lifted, with more data released than ever before.

Telling the human stories behind the statistics

We did not just publish the numbers – we told the human stories behind them. This was not forthcoming from any published US information, which simply labelled the dead as militant or non-militant. With strikes happening in remote areas and few on the ground investigations carried out, this meant no real information about thousands of people. We sought to change that. Aside from addressing the tragedy of people dying in obscurity, unnamed and unacknowledged, we also sought to address the fact that the public and policy makers could not properly test whether drones are “highly precise weapons” when so little was known about who was actually dying.

To highlight just a few examples, our Naming the Dead project identified 732 people killed by CIA drone strikes in Pakistan, establishing that hundreds of them were civilians and putting faces to names wherever we could. In 2017, together with freelancers Namir Shabibi and Nasser Al Sane, we investigated President Trump’s first military operation, a botched raid in Yemen, where we found that nine young children had been killed and reported the harrowing accounts of survivors. The Pentagon was eventually forced to admit that their version of what had happened was false and ours was true.

In 2019, in collaboration with The New York Times we told the story of Masih, a man in Afghanistan whose wife, seven children and four young cousins were all killed in a single US strike. And in our most recent project, we investigated 25 strikes that happened since June 2018, confirming in 10 cases that they had hit civilian homes with family after family being wiped out.

Survivors told us that being listened to and having their story told to the world had a profound effect on them, in a landscape where any form of accountability or justice is incredibly hard to come by.

From left to right, Masih Ur-Rahman Mubarez’s children Fahim (5), Mohammad Fayaz (4), Mohammad Elyas (8), Mohammad Wiqad (10) and Samina (7)

From left to right, Masih Ur-Rahman Mubarez’s children Fahim (5), Mohammad Fayaz (4), Mohammad Elyas (8), Mohammad Wiqad (10) and Samina (7)

Accountability

As well as transparency, our reporting provided accountability. We took our data, findings and human stories from our on-the-ground investigations back to the US military time and again, getting answers that had previously not been forthcoming. In many cases we got admissions of strikes and possible casualties that had previously been denied. In some cases our work resulted in condolence payments being made to survivors.

In 2019, working with The New York Times, for the first time we were able to forensically prove US responsibility for a strike that killed an entire family, in the face of repeated denials. The US had initially denied a strike had taken place in the area on the date in question; after being confronted with our findings it later said it was possible the area had been targeted but there were no civilian casualties; after being confronted with yet more evidence it ultimately conceded that the strike had been carried out and it was possible there had civilian casualties.

This investigation was part of The New York Times’s winning submission for the George Polk Award and has been selected as a finalist for the Amnesty Media Awards Investigation of the Year 2020 (winners to be announced later this month).

Our final project proved that 10 strikes on civilian homes killed a total of 115 civilians, of which more than 70 were children. We also confirmed one strike on a building housing an NGO which led to a further 2 civilian deaths. We know nine of these attacks were carried out by the US. Our dialogue with the military in relation to our findings is ongoing.

CIA black sites

Our team did not just examine drone strikes but many other covert US security operations and activities. In collaboration with the Rendition Project our reporter Crofton Black investigated the use of rendition, secret detention and torture by the CIA between 2001 and 2009. The work, published in 2019, resulted in the most comprehensive history to date of who was held by the CIA, where, and what had happened to these prisoners, whose fates were almost entirely unacknowledged by the US or their own governments. Our investigation helped the US Senate Intelligence Committee to correct errors in its own heavily redacted list of CIA detainees.

Make change possible

Investigative journalism is vital for democracy. Help us to expose injustice and spark change

Click here to support usCrofton Black went on to testify at the European Court of Human Rights in two cases in which eastern European countries were subsequently found by the court to have hosted secret CIA jails. He also briefed members of the European Parliament on his research.

The private firms tracking terror targets

Our 2015 investigation into the corporate outsourcing of drone warfare revealed for the first time that the US military was paying private sector contractors millions of dollars to review and analyse drone video feeds, helping to identify the people spotted in them as enemies or civilians. The contractors’ determinations on whether a person was holding a rifle or a shovel, for example, would then influence whether or not they were likely to be targeted and killed. “When you mess up, people die,” one analyst told us.

Fake news and false flags

In one of our most widely read stories from the project we revealed the Pentagon had paid the British PR firm Bell Pottinger $500m to run a covert propaganda operation in Iraq. The company had been contracted by the US military to produce newsclips which were given to local TV stations – but also masterminded a secretive operation to drop fake insurgent videos in raids and monitor their spread.

Inside the world of privatised war

In early 2019 we went inside the private security industry to investigate how more than a dozen embassy security guards from Nepal and India died in a bombing in Afghanistan, and what this tragedy told us about the corporate outsourcing of war. In doing so we uncovered details about a security firm that made big money in the Iraq war and then mysteriously disappeared.

Innovative methods

Long before OSINT was a commonplace term, the Bureau was doing it. The impossibilities of accessing remote militia-controlled areas meant we relied on open source data over the years. Local media reports, international media, social media reports, legal affidavits, different military datasets, Pentagon procurement records, leaked US intelligence reports and Wikileaks cables are among the different sources we have dug into from our desks. In recent years we have combined this with satellite imagery and photographs to carry out geolocation and other visual investigation techniques.

The private firms at the heart of US drone warfare and Bell Pottinger stories were both products of a completely new data-mining system which we built to analyse millions of records of transactions between the US Defense Department and contractors. The records were public but our bulk analysis of them produced new insights and revealed previously unreported covert operations.

Recently we undertook our biggest open source investigation to date, investigating 21 strikes that had reportedly killed civilians with volunteers we connected with through Bellingcat.

Reaching different audiences

We thought creatively and strategically about how to reach different audiences. As well as publishing in international and regional outlets, we published academic reports, submitted evidence to inquiries, built relationships with civil society and politicians, and in recent years translated articles and tweets into Pashto and Dari in order to reach Afghans affected by the issues we were reporting.

A multi-talented team

As well as pioneering new methods of desk-based reporting and new distribution formats, we did in-depth reporting on the ground thanks to talented reporters that we worked with in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia. We would like to pay a special thanks to Chris Woods (who initially set up the project and now runs Airwars), Alice Ross, Jack Serle, Owen Bennett-Jones, Abigail Fielding-Smith, Crofton Black, Jessica Purkiss, Payenda Sargand, Mohammad Jawad, Ruhullah Khapalwak, Abbie Cheeseman, Namir Shabibi and Nasser Al Sane. They were able to get access to information, places and people that other international media often did not.

Moving on

Crofton Black remains at the Bureau, now heading up our Decisions Machines project investigating the use of algorithms, AI, big data and machine-learning by public bodies. Jessica Purkiss, who led the Shadow Wars reporting over the last two years, is now working as a freelance journalist in Beirut; she can be contacted here.

All our investigations from the duration of the project will remain on our website and can be found via our Shadow Wars and Drone Warfare project pages. Our data counter and spreadsheets documenting the details of strikes and casualties can also be found via our Drone Warfare page but they are now static and will no longer be updated. Ongoing US strike monitoring and casualty-counting work for Somalia, Yemen and Pakistan will be continued by Airwars, a not for profit set up to monitor and assess civilian harm from airpower-dominated international military actions. The organisation also engages with militaries where productive, including the US, to help improve understanding of civilian harm and reduce battlefield casualties.

Header image: The aftermath of a strike in Afghanistan

Our Shadow Wars project was funded by the Open Society Foundation and the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.