Investing in local storytellers is vital for the future of news

Bureau Local director, Megan Lucero, on how investing in journalism on the ground is paying off

The fight for the future of news is local.

For the past two and a half years, this has been at the heart of the Bureau Local.

In 2017 we set out to build a people-powered network that would set the news agenda and spark change from the ground up.

We began working with other reporters and citizens on local-to-national collaborations, sharing localised data, publishing findings across the UK and mobilising our collaborators to share and act on the work.

While this work was needed, valued and has provided effective impact at scale, we quickly realised that the sector was haemorrhaging money and losing reporters fast.

We set out to make sure that a portion of the money we fundraised would make it back into the hands of local reporters.

In 2018 we launched our Local Story Fund and awarded local storytellers with roughly £1,000 per project to pursue important local stories. We also provided editorial, data and production support to publish these stories with us and local and national partners.

The result was a profound example of just why local news matters and why we need to invest in it. The reporting shone a light on the realities of underreported communities, held local politicians and companies to account and even changed local policies.

Here’s a recap of the great work that came out of our Local Story Fund

Emily Goddard investigated the rise of youth homelessness in Milton Keynes. She was shocked to find that in 2018 a third of its rough-sleeping population was under 25, which is four times higher than the national average.

She worked with a photographer Alex Sturrock and interviewed and photographed some of the young people trying to make it on the streets. This includes James*, who became homeless at the age of 16, and Kane*, 22, who had been homeless for five years and lived in a tent in the underpass. In a chilling conversation, he said, “In this place, the only thing that grows quickly and properly is darkness.”

Following the story, the council sent Emily a press release saying they had housed several people who had been sleeping rough; and for a short while after she noticed a reduction in the number of tents. Yet a year on, a large number of tents are pitched in the centre once again.

Alex’s photographs brought the dark reality of the Milton Keynes “tent city” into focus. One that particularly struck us was a snap of a food-delivery robot passing by homeless tents. We’re proud to say that our initial collaboration has led us to commission him to photograph many other projects, including an important story in Oxford.

A food delivery robot passes by homeless people's tents in Milton Keynes

Alex Sturrock

A food delivery robot passes by homeless people's tents in Milton Keynes

Alex Sturrock

In August 2019, Anna Wagstaff and Gill Oliver reported on the 15-year life expectancy gap between the rich and poor in Oxford.

They showed the effect that working at the nearby car plant had on Joe Richards, a resident, while the local pharmacist described how medication for depression is the third most common prescription he fills, after diabetes and heart disease. After a piercing look at available services and livelihood in the community, they documented how austerity and poverty played a huge role in the health of the community. The story ran in Leys News, the Oxford Mail and the New Statesman.

Following the publication of the story, we supported Anna and Gill to hold a live event in the Leys News newsroom in Northfield Brook. NHS Trust governors, councillors and residents came to discuss the steps needed to tackle health inequality in the community.

At the meeting, one of the key points suggested was making the “health impact” a much stronger priority in the county’s industrial strategy, and the reporters met with Ansaf Azhar, the head of the department of public health at Oxfordshire county council, to discuss this idea and follow up.

At a community level, one campaigner who attended the meeting is building an alliance of councillors and public health professionals to lobby for an Oxfordshire Living Wage to be recommended in the next Director of Public Health annual report and the 2020 Oxfordshire Joint Strategic Needs Assessment. The impact even extends to small kindnesses. After reading the story, one of the residents of North ward set up a community group to bring her neighbours together with locals of Northfield Brook.

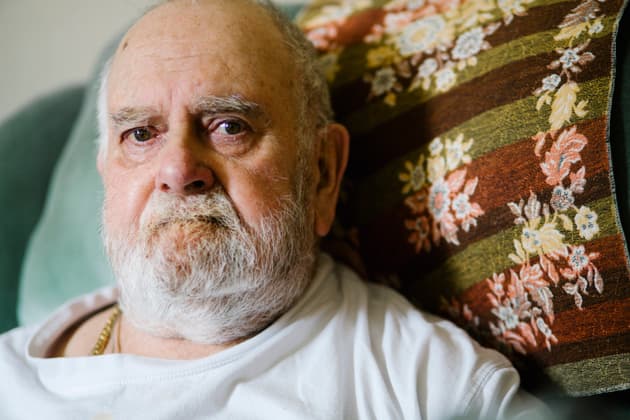

Joe Richards spent most of his life working at the Cowley car plant but now struggles to pay for his care

Alex Sturrock/TBIJ

Joe Richards spent most of his life working at the Cowley car plant but now struggles to pay for his care

Alex Sturrock/TBIJ

In collaboration with Portsmouth News, Kent Messenger and the Southern Daily Echo, Luke Barr revealed "horrific" delays to wheelchair access from one of the NHS’s biggest providers.

After crunching the numbers on wheelchair waiting times across the country, Luke showed how delays in wheelchair deliveries were commonplace.

He dug further and found that 14 of England’s 30 worst-performing wheelchair services for waiting times in 2017 and 2018 were in the southeast of England and all were run by Millbrook Healthcare. Luke spoke to several people who had been let down by Millbrook, including Cariad, a 15-year-old who at the time was the oldest child in the UK with type 1 spinal atrophy, had to wait nearly two years for her chair.

Wheelchair users told Luke that they were grateful to have this story published, particularly given the stress and frustration many had been through. Yet little has changed for Millbrook. The company was recently purchased by a private equity fund and continues to provide NHS services. Complaints continue to stream in on social media.

Cariad Howat needs a wheelchair that can recline in order to feel comfortable

Photo by Morten Watkins, Solent News and Photo Agency

Cariad Howat needs a wheelchair that can recline in order to feel comfortable

Photo by Morten Watkins, Solent News and Photo Agency

Hanan Bihi told the story of entire families threatened with eviction by Wandsworth council when young relatives in council homes were placed on the “antisocial behaviour” list. Hanan had gained the trust of three mothers in the borough and translated their interviews for publication in which they said the council made them choose between their children. It was a powerful account of families whose voices often go unheard. We co-published with the Wandsworth Times and the New Statesman.

The work was celebrated by Tony Belton, Latchmere Labour councillor, who had spoken out against the policy, which was introduced after the London riots in 2011. Aydin Dikerdem, Labour councillor for Queenstown, said: “The reason austerity has gone so unscrutinised in my opinion is because of the death of local media outlets. Great to see you challenging this.”

Sirad, one of the women who was forced by Wandsworth council to chose between her son and her home

Rob Stothard/TBIJ

Sirad, one of the women who was forced by Wandsworth council to chose between her son and her home

Rob Stothard/TBIJ

Jane Haynes reported on the extreme end of unpaid internships in the UK. After conducting an in-depth search of prominent job websites she found, on a single day in 2018, 67 unpaid internships that were for at least three months – four being for a whole year.

Many of the ads suggested that the intern would have a high level of responsibility and be “in charge”, “PA to the managing director”, and the “right hand of the creative director”. An employment rights and tax specialist said such internships could be in contravention of minimum-wage regulations.

Those advertising included high-profile organisations such as the UN, Harvey Nichols, think-tank Chatham House and Climb Online – the company of Mark Wright, the winner of TV show The Apprentice.

Several employers removed the ads after being contacted by the Bureau and even moved to change their policies; some stand by their unpaid programmes, while others are looking to reform their schemes.

Mark Wright with Lord Sugar

PA Images

Mark Wright with Lord Sugar

PA Images

Natalie Bloomer and Samir Jeraj reported on an important local story about a night shelter in Northampton sitting half-empty at a time when there had been a series of homeless deaths during the winter of 2017/18.

The story made a stir in Northampton. We partnered with the Northampton Chronicle and Echo who ran it on the front of the newspaper and four pages inside. BBC Northampton dedicated nine minutes on air with Natalie and other local press picked up the story.

Since the story came out there has been change on the ground – especially for those who are now let into the shelter.

Local homelessness services have told the reporters that the shelter is almost always full now (while it was only half full for the period we looked at). The council has taken on more outreach workers and has been working with local charities and street-level services on new ways to tackle homelessness in Northampton.

A young rough sleeper in Northampton

Alex Sturrock

A young rough sleeper in Northampton

Alex Sturrock

Money talks – we need to invest

It took us just over a year to dig into, support and co-publish all six of these local stories. If that sounds like a lot of time to you, then you’re not alone.

Investigative journalism takes time and investment. During the process of reporting we pulled together reams of documents and data and conducted our own analysis; we spent time in communities, talking to people who have experienced these issues firsthand and it often took time to gain trust and access; we requested comment from companies and councils and worked with them to tell the story accurately; we independently fact-checked each and every statement and claim with original sources; we worked responsibly with lawyers to ensure our work is legally sound. Add all of this to the time it takes to chase leads, hit dead ends and find truths that some want to remain hidden.

At the end of the day, proper financial investment yields quality journalism.

Nearly every reporter we worked with said that their reporting would not have been possible without the financial support they received. A few reporters described it as an “incredible freedom” and a “luxury” that has been long lost to local reporters.

They also said that our help with data crunching, editorial scrutiny and support were crucial factors in making these stories impactful in a way that local journalism was – and should continue to be – known for.

We are currently exploring how we can continue to provide this kind of support in the future. We invite our industry to join us in investing in local storytellers.

* names have been changed

Join the investigation

Become part of the Bureau Local – our collaborative network of reporters and citizens – and tell stories that matter.

Find out more