“What voices are not heard” - how journalism is changing and how we want to be a part of the change

Just this week the Holland-based news organisation, De Correspondent, launched its US crowd-funding campaign for “unbreaking news”, to take its work global. The latest figures are impressive - thus far (and counting), over 8,000 members across the globe have pitched in to fund the campaign. These are exciting times for newsrooms that commit to engaging deeply with their members and audiences and De Correspondent is one of the organisations leading the way.

We started researching how we engage with communities just over a month ago. Since then, I’ve been talking to readers, academics, journalists, business-people and charities, to gather more information on how other organisations encourage people to participate in their work.

I’ve also been talking to our journalists at the Bureau to get a better idea about their own topic areas, how they listen to those who care about the work they do and how we could involve those communities and audiences more actively in our work. After all, we need to make this move together as an organisation; it’s not down to any one person, as De Correspondent and other engaged newsrooms make clear.

Our journalists at the Bureau work in four main areas at the moment - global superbugs, shadow wars, food and farming and then, in a different model, our Bureau Local network. Talking to our teams, I’ve been struck by how they already participate enthusiastically with different networks - but also how that engagement varies from team to team.

For example, the Bureau Local is powered by a 800 strong community of journalists, technologists, designers, concerned citizens and people with specialist knowledge who work together on issues that are in the public interest. For example, coders help journalists with tech tasks; designers build visualisations for newsrooms; members of the public provide information; experts bring forward contacts and insider knowledge; journalists share resources, quotes and findings.

By working with our members we can share our national investigations on subjects such as council cuts and domestic violence at the local level. But this isn’t a one way street, the team stresses - the knowledge and scrutiny of issues at a local level, informed by our initial work, then deepens our national understanding as we get information back. It’s much more like a circle of knowledge and engagement, not a linear line where we merely broadcast information from ‘us’ to ‘them’.

Bureau Local director Megan Lucero explains: “Our work focuses on mobilising communities around our journalism and ensuring we report with, and not just on, the communities we cover. We run online and offline community forums, meetups and live journalism events to bring our stories to everyone.”

This collaborative journalism model with local members differs from other strands. For example, our antibiotic resistance team works very closely with a core group of scientists and campaigners for global health awareness, but acknowledge that the general public’s awareness of the threat of global superbugs, and thus their participation, is still in the early stages. During the project the team has co-published with scientists in medical journals, collaborated with journalists in countries including Malawi, India and Afghanistan and also engaged at the governmental level, both at our Westminster parliamentary launch of the project and also more recently at a UN summit in New York. But we’d like to draw the general public, so affected across the world by this scourge, into the debate as well.

Our food and farming project is once again different, as we work closely with the Guardian on its Animals Farmed series, whereby the paper partly funds our journalism on the issue. Therefore, we decide on investigative priorities together as partners in a series that has seen us dig into American-style beef lots being introduced quietly in the UK, how Parma ham in Italy is really produced and other subjects such as the risk of food contamination.

There, collaboration with our media partner is key to our work, and from that flows reaction from a wider Guardian readership and onto social media platforms where we are active.

For instance, we ran a big social media campaign informing the public about which UK supermarkets were using American style feedlots, with reaction and pushback online from the public about whether this was an intensification of British agriculture and if so, whether it was justifiable. We had a more active response because our social videos raising awareness of both that story and Parma ham, for instance, were embedded in Guardian stories, thus giving us far greater reach than we would have had if we had published merely on our own website.

I also talked to our foreign desk about the stories that they do, both on covert wars around the globe and other ongoing investigations. Our reporters have welcomed responses from readers over many years, particularly on drone warfare, but are understandably wary of being overly transparent in the early stages of some of their investigations. How, for instance, would a very open attitude to investigating secret US CIA torture camps have helped us to investigate that story? Would it instead have led to the CIA concealing their location further and possibly moving them elsewhere? One of the team says that there is definitely a role for transparency but with particular audiences and communities at key times, rather than being an ongoing process right through every investigation. The team also notes on drone warfare, for example, that some of the most engaged readers have been artists who can be great at communicating and amplifying the public’s understanding of drone warfare but are unlikely to be potential sources and engage in exchanging information.

So engagement with our communities is not one thing - it’s many and is adapted around the needs of our readers and also how they would like to disseminate our work and use it themselves. Our collaboration model is complicated, but not in a negative way.

With this in mind, I recently attended the European Journalism Centre’s (EJC) News Impact Academy, in conjunction with the Google News Initiative, in Warsaw, Poland, looking at membership and participatory models for journalism, along with around 20 other news organisations from all over Europe. Emily Goligoski, research director for New York University’s Membership Puzzle Project, led the two day event. There were many great insights at the Academy, both from other journalists and from Emily herself. Here’s the EJC’s Medium post on the News Impact Academy.

Goligoski advises: “Think about your readers’ and listeners' needs: to learn, be of service, be appreciated, meet people with shared values, and more. And your site's needs: to create high quality journalism, find people who can benefit from that work, make money at it, and identify more ideas for work the world wants. There is likely overlap in those two sets of needs, and it’s your job to identify what and how.” She adds that Bureau Local’s approach, of reporting alongside communities, is increasingly seen as important and replicated elsewhere.

Thinking about participation more at the News Impact Academy, I realised that we need to understand that we speak to and with different communities differently on our disparate topics - and that’s fine. Sometimes transparency with an ongoing investigation is great - as with Bureau Local stories, where the stories are opened up at an early stage to our members, who have access to our data and reporting recipes. With other topics, transparency may be with a group of engaged experts to start off with, before being widened out around publication to readers and communities, when we might ask them if they want to pitch in on a call to action, for instance, as we did when we asked people if they would like to respond to the government consultation on CCTV in abattoirs, following some of our work highlighting cruelty in some slaughterhouses. But the core of all our work, surely, should be that we welcome participation, responses - and listen to what people are telling us. If that’s a given the question becomes how we collaborate, not if.

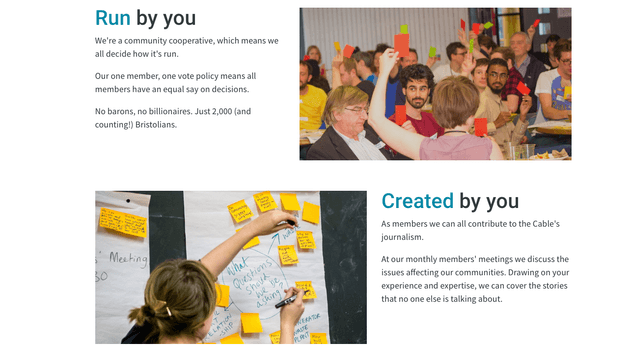

At other news organisations, like De Correspondent, the model is to engage on almost all stories, right from the get go and journalists even have this written into their job descriptions. At some organisations readers can choose what some of the investigations should be - the Scotland based news organisation, the Ferret, involves its members in story selection and they selected fracking as their first story - a similar model to that at the Bristol Cable, a news co-operative in the West Country, serving local people.

Bristol Cable website explains how it involves its members

Bristol Cable website explains how it involves its members

Adam Cantwell-Corn, one of its founders, explains how the Cable has democratised decision-making. “In the Cable's 2018 AGM, 100 members were asked how we could improve our journalism. One of the most decisive outcomes was for the Cable to produce more stories with direct links to local communities. As well as voting members discussed how to deliver on the Cable's promise of amplifying lesser heard voices. In responding to this mandate, the editorial team asked - What voices are not heard, and even what communities are actively marginalised by too much of the media? Of course there are many. But Gypsy Roma Traveller communities particularly stood out. From there Cable journalist Hannah Vickers researched and presented a series idea to the team and launched Cable's Moving on: Bristol's “last acceptable” racism. We will be hosting an event on the series with people from the GRT community early next year.”

We also looked at how to define a new mission statement for a more participatory newsroom whilst at the Academy. In the spirit of sharing, I’m interested to know from you as we think that formulation through. What defines the Bureau in your opinion, who do we serve best, what do we do well and what could we do better? We know a bit about this from surveys over the last couple of years, but over the next few months would love to hear more responses - please do contact us with your own ideas. One of our staff members, for instance, comments that there is a real sense that the Bureau’s work is important but can be niche. She asks: how do we make sure that our stories are applicable to people's’ lives and how do we translate the importance of the work we are doing on topics like superbugs so the general public understands the importance of that work to them and their families? Another adds that we are still best known by our industry, i.e., other journalists, rather than the general public. How do we create a more accessible identity, she wonders, and how would we keep a promise to not only listen to our communities more, but also turn that listening into investigations. How do we, crucially, start to centre our skills of listening and collaboration as a key measure of our success?

As always, we want to hear from you. Contact us on Twitter, Facebook, or via [email protected] - or comment directly on this blog. I’ll be sure to respond. And sign up to our newsletter below, for all our updates.

The Bureau newsletter

Subscribe to the Bureau newsletter, and hear when our next story breaks.

My own opinion is that our stories work best, and have the best chance to spark change (part of our current mission statement) when we work alongside, rather than speaking for, people who are involved in them. That’s as true of victims of drone attacks in remote Afghan villages, as it is of women who’ve lost their wombs in Malawi and the doctors fighting to save them, and the relatives and friends of homeless people who’ve lost their lives on UK streets. We hope that by listening better to people, we can lay bare the effects of government policies and the private sector on individual citizens, wherever they are in the world. And then by giving people information, we give them the toolkit to question those in power.

A last couple of questions from me, as we develop our plans for a more global, outward facing Bureau - how should we interact with both local and global audiences? How should we support individuals to hold power to account on the wrongdoings we uncover through our work, wherever they are?

Header picture, of homeless people in Milton Keynes, UK, cooking outside, by Alex Sturrock